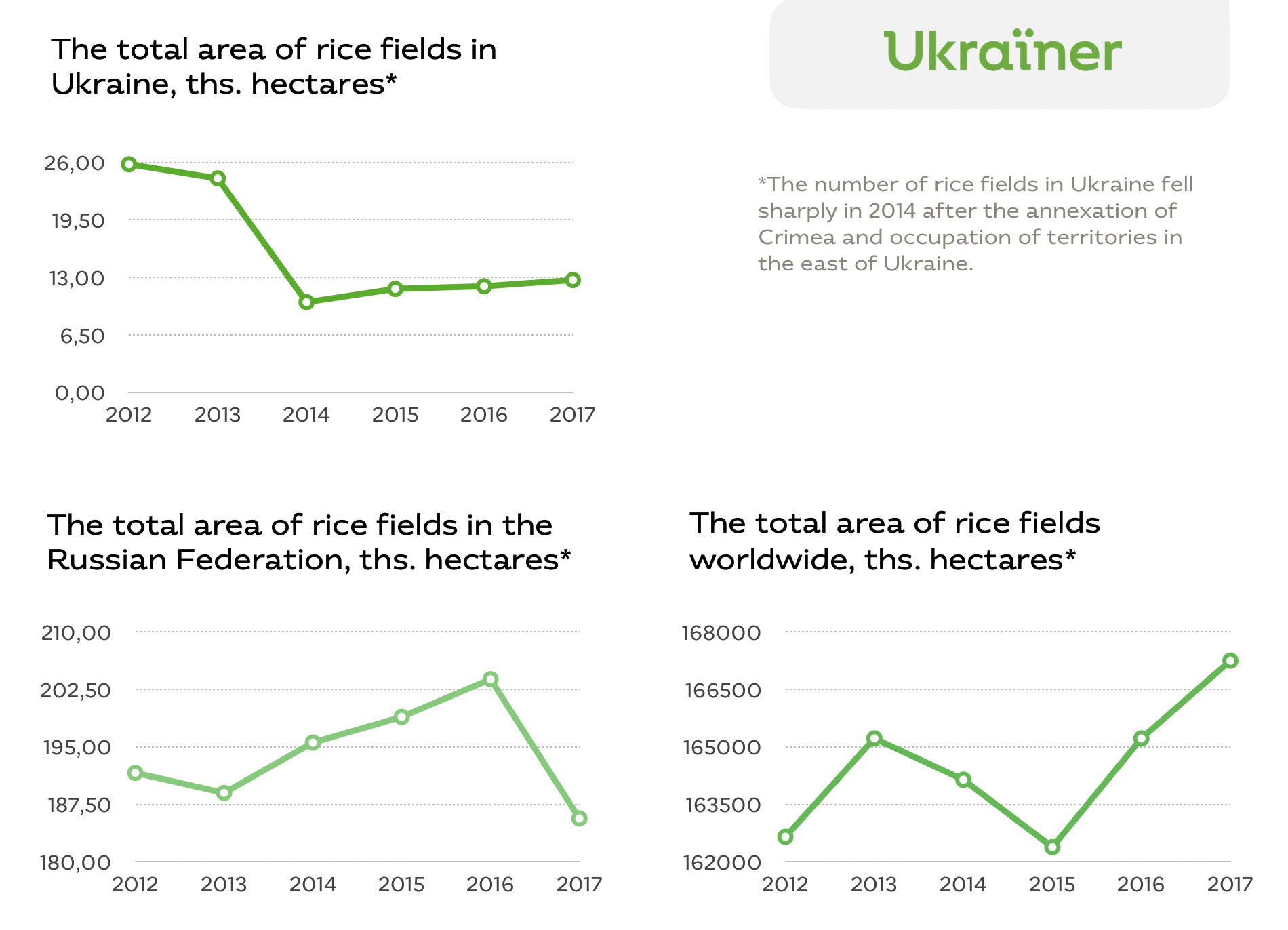

Does the thought of rice plantations immediately remind you of Thailand, Bali, and Vietnam? On the contrary, rice has also been cultivated in Ukraine since the beginning of the 20th century. In the past, more than half of all Ukrainian rice was produced in Crimea, but after its occupation those fields are no longer being used as the occupying power could not preserve them. How and why did Ukraine receive the third most popular agricultural crop (after sugarcane and corn) in the world?

Rice is considered to be a common product in Ukraine, although it is actually an exotic crop for our lands and has come a long way from Southeast Asia, going through many years of adaptation in order to become available in the Ukrainian market.

The idea to cultivate rice in the territory of Ukraine is considered to have been developed as far back as the 18th century. The first mention of large-scale cultivation of these crops in Ukraine, namely on the floodplains of the Southern Buh, dates back to the 1930s. At that time, field research was conducted on the possibility of growing rice in different regions and the first irrigation systems were built.

Floodplains

Coastal territory that may be fully or partially flooded during a snowmelt or heavy rain.During World War II, all of the irrigation systems for the rice crops were ruined. They were able to be restored after 1949, but the imperfect technologies of the time did not provide a high-quality harvest.

The Krasnoznamianska and Inhuletska irrigation systems were brought into operation in the beginning of the 1960s, giving rise to mass rice farming in Tavria and Bessarabia. The use of these types of rice systems has significantly increased crop yields.

Ukrainian rice today

Compared to the average Chinese person, who consumes about 77 kg of rice a year, the average Ukrainian only eats a little of this grain — up to 3 kg. Until 2014, Ukraine provided for 70% of its own rice and imported the rest, mostly from Pakistan or Turkey. On 60 thousand hectares of rice irrigation systems located in Tavria, Prychornomoria [Black Sea region], and Bessarabia, 170-180 thousand tons of crop were harvested per year. 80% of the sown areas was occupied by domestic rice, which today has 11 registered varieties.

With the occupation of Crimea, Ukraine lost nearly half of its rice farms. In addition to the fact that the peninsula was one of the centres of rice production, it was a place where researchers and rice farmers would often travel in order to conduct experiments and exchange professional experiences. Now rice doesn’t grow in Crimea due to the absence of water in the Northern Crimean canal: it was closed and is now becoming overgrown.

Today in Ukraine, 30 thousand hectares are allocated to irrigation systems, and rice grows on an area of 12-13 thousand hectares, providing the country with less than 40% of its rice. It seems that such indicators do not predict a successful future of rice production in Ukraine, but an employee of the Institute of Rice of the National Academy of Agrarian Sciences of Ukraine, Dmytro Shpak, believes that this is not a reason to ditch rice cultivation as long-abandoned lands are getting new life:

“They are being restored and expanded. Especially around Hola Prystan village. There used to be rice systems there, and now they are being restored. We have started receiving orders from those farmers; some of them come to visit our institute to learn and try something new.”

In addition to this, over the past few years drip irrigation technology has been introduced (the supply of water is limited and provided locally to the root of the plants. — ed.). This makes it possible to grow rice in regions that, it would seem, don’t have favourable conditions. On the territory of Ukraine, only the south, namely the coastal areas, is best suited for the growth of this crop. It requires lots of water and heat, sprouts only at moderate temperatures and dies in the heat or cold; sandy, salty, or swampy soils are not suitable for the cultivation of rice. However, drip irrigation makes it possible to significantly expand the range of rice farming. Thanks to this technology, less water is used (the irrigation source can be any kind of reservoir with suitable water), than during the traditional flooding method.

The process of sowing rice

Unlike the majority of rice-producing countries, which use seedling technology (when seeds are grown in a greenhouse, and then transplanted to open ground. — ed.) in Ukraine, rice is sown. The Institute of Rice explains this choice by saying that it is a simpler method and requires less people.

Before the sowing, which begins in May, the land goes through several stages of processing. First, a tractor levels the ground on the field. Then it is cultivated, fertilizer is added to it in order for the rice to grow in a favourable environment. After the rice has been planted, paddies — plots of arable land with rice crops fenced off with dirt walls for water retention — are supplied with water from reservoirs through special supply networks. This process is called ‘primary flooding’. When the seeds sprout, the water supply stops. Water is removed from the paddies and rice begins to drain. When green leaves appear, the paddies are again flooded with water. The water supply continues to the end of the season (early to mid September), when the rice is ripe. During the growth process, the rice is constantly cared for and given necessary fertilizers.

Usually the rice field is not only planted with rice. Half of the area is sectioned off for other crops, such as soy, wheat, or barley. Additionally, in order to prevent a decrease in yield, rice on one paddy is grown for no more than three consecutive years.

Antonivka. Institute of Rice

Successful Ukrainian rice farming originates from the coastal area in the south of the country. Now, located in the local village of Antonivka is not only the biggest plantation of rice in Ukraine, but also the Institute of Rice.

This institute, which previously was a rice research station, is the only scientific centre in Ukraine that researches this crop, creates new varieties and develops technologies.

Here, the development of rice farming in Ukraine is conducted by a little over 50 people: from the director Volodymyr Dudchenko, who has already been researching the crop for over 20 years, to employees who for 40 consecutive years have been improving rice sowing technologies.

Under the leadership of Dmytro Shpak, the head of the rice breeding department, eight varieties of the crop were bred: Viscount, Premium, Ontario, Marshal, Consul, Lazurit, Bassoon, and red rice, which is still being tested. According to Shpak, the producers have different needs, but they are all focused on the end consumer, so the employees at the Institute of Rice try to help them create the highest quality product:

“The aim is simple: to breed a variety that anyone would happily buy and plant.”

Ukrainian rice in stores can be identified by two signs: it is round and polished. Yet another important characteristic of Ukrainian rice is that it can be grown on both Ukrainian and East Asian lands:

“Their varieties are short lived, they don’t grow here and don’t produce grain. We get hay, roughly speaking, from their varieties. However, our varieties grow in their conditions.”

Adapting the crop that comes from South-East Asia to cultivate on Ukrainian lands is an essential task and the greatest difficulty for breeders because the climate in the East significantly differs from Ukrainian.

“This is all about the ‘heat supply’: In Asia they have one, we have another. The growing season for them is longer, and for us is shorter. Therefore all of the difficulties of breeding was to transform this type of rice, which grows there, to adapt to our conditions. That is, to reduce the growing period and make it more cold-resistant, more suited for our conditions. That was the problem. Now it is partially solved.”

Growing area and Rice paddy art

Near the institute there is a growing area where hybridisation (crossing) of parent forms of rice takes place. This process is very important for breeding, that is, the creating of new varieties.

At the end of May, the open-sky laboratory comes to life. Rice is planted in lysimeters (devices that measure the amount of water that has seeped deep into the soil) and flooded with water. In vegetative pots, which resemble ordinary buckets, the parent forms of rice are planted, which later have to bloom all at once. A rain gauge and automatic weather station monitor weather conditions. Aside from rice, a whole collection of aromatic and medicinal plants are also grown in the growing area.

slideshow

In the daily routine of breeders, there is also a place for creativity. A few years ago, a rice plantation became a canvas for a work of art for the first time.

“It happened spontaneously at first. We just realised: there is a rice breed that has a black leaf and all the organs of the plant are black. We tried to plant it in a particular way to “write” the word ‘rice’. The next year we “drew” the “yin and yang” symbol this same way.”

Then in 2016, the Institute of Rice joined in the celebration of the 25th anniversary of Ukraine’s independence by growing rice in the form of a large trident 24.7 meters long and 16.4 meters wide in the field. The following year, 1,360 square metres of rice transformed into a huge portrait of Ukraine’s national poet — Shevchenko. In doing so, the Institute of Rice set two national records.

slideshow

Kiliiskyi district. Lisky

In the past, the Kiliiskyi district, which is in Bessarabia, was rich in rice plantations. Now rice farming is carried out here only in Lisky, Kilia, and Sarny.

In particular, the village of Lisky has a large rice plantation. This rice system was built here in 1978 by the military when they opened the Danube-Sasyk canal. In 2004 Oleksandr Dubovyi, the director of the company “Ris Bessarabii” (Rice of Bessarabiai), started to restore what was left of the bankrupt state farm. Ris Bessarabii is the biggest producer of this crop in the region. The entire farm occupies 4,500 hectares of land, from which almost 2,000 hectares are allocated to rice, and the remaining land grows rapeseed, barley, and other crops. Since rice bodes very well on these lands (2016 was one of the most productive years: from 1 hectare, 12 thousand tons of rice was harvested), the farm plans to allocate a larger plot for rice farming.

“The number of rice fields has not decreased — on the contrary: If about 8 years ago we grew rice on 500 hectares, then this year we’re already growing on 1,600. Every year we add a little more: about 100 or 200 hectares.”

Rice fields are served by the “Lisky-3” pumping station, which supplies water from the Danube to the paddies. During the season, which lasts from the beginning of May to the end of September, 120-130 people work on the farm, but in the winter there are less employees, because there is not much to do. Ris Bessarabii attempted to export rice to Turkey and Romania. The first attempts were unsuccessful because of logistical issues, but recently Turkish families have been trying rice from Bessarabia.

Ivan

One of the specialists devoted to rice farming was Ivan Cheban — the chief hydraulics technician on the farm, who for 6 consecutive years was responsible for ensuring that water got from the hydroelectric plant to the paddies. He did not arrive at rice farming right away. He studied zootechnics, loved animal husbandry, and worked on a farm in Lisky. Moving to Lisky, he became acquainted with hydraulics technicians, with whom he lived for half a year. They shared their professional experience with Ivan, and he moved into the agricultural holding of Ris Bessarabii. To work as a hydraulics technician means to renounce domestic work and really any kind of a personal life, Ivan says:

“And in this work, you need to be meticulous and need to know the rice system very well because this is not a “water moved, that’s all” system. This is all essential care and a lot of work. A work day, I would say, takes up almost 18 hours.”

Such a work schedule is due to the fact that the hydroelectric plant doesn’t operate for only 6 hours a day (3 hours in the morning and 3 hours in the evening) — because the value of electricity is the highest at these hours. While the water intake is going, it is necessary to be present at the station in order to quickly settle any pipe breaks or other technological malfunctions and avoid losses.

Despite the difficult and exhausting nature of the work, Ivan loved his job and enthusiastically talked about how rice grows, or even “whispers” in the wind.

In November 2019, Ivan Cheban, a hydraulics engineer at Ris Bessarabii passed away, and in December 2019 the head Oleksandr Dubovyi passed away.