Nomadic life in a pavilion, guitar songs at the fireplace, passion and easy luck. This romantic image of Roma known from literature and soviet movies is long in the past. Instead, the stereotypes about the poor nation living on social payments for a great number of kids, stealing or dragged into criminal activity are more common today. Some modern Roma, living in discreet settlements, are isolated from the rest of society. Poverty, lack of education and troubles with employment make this bias even stronger.

Stereotypes and even more — xenophobia — have been imposed to ethnical Ukrainians since their childhood. “Be polite, otherwise gypsies will kidnap you!” — the children were scared. “You are muddy like a gypsy.” The stories of Ukrainian folklore also show Roma not always as positive characters. Since their childhood, the majority of the Ukrainians have confidence that the Roma can hypnotize them or steal something and, therefore, guided by fear, they avoid them in every possible way.

However, all this is hardly more than a myth that occurred due to the lack of information about how Ukrainian Roma live. Having been living alongside with ethnical Ukrainians for already many centuries, Roma still remain the people the image of which is full of mysteries.

One of such mysteries is the number of the Roma population. Today, there are no clear data about how many Roma live in the territory of Ukraine. And getting these data is really difficult indeed, as many Roma have no documents. Some of them intentionally hide their origin, which is totally understandable. Historically, during various war periods different ethnic minorities (including Roma) all over the world suffered from repressions, persecutions and pursuits.

slideshow

According to the population census of 2001, there are 47,587 Roma living in Ukraine with one-third of them — in Zakarpattia. However, public organizations consider this number to be no more up-to-date. European Council estimates the approximate number of Roma community in Ukraine at 120-400 thousand people. According to the data of Roma public organizations, there are over 40 thousand Roma currently living in Zakarpattia. The majority of Zakarpattian Roma live in small settlements.

Small settlements

We intentionally use this term instead of the traditional word “encampment”.Right here, in Zakarpattia, there have been preserved the largest number of Roma language dialects, differences in customs and level of education. Although Roma live just a short distance away, often on the neighbouring street, their community is still the most obscure for the rest of residents of Zakarpattia. We have visited some Roma settlements of Zakarpattia to see how Roma live with our own eyes.

slideshow

Dubove. Baron Ivan

One of the Roma settlements is located in Dubove village, Tiachiv district. It was founded in the 1950s. Seeking employment, Roma were coming here from neighbouring villages and towns. Dubove village leader of that time offered Roma work at the local factory and later suggested that they should stay there. Thus, the settlement, where 64 people live, emerged inside the village. The former local baron, i.e.the formal leader of the village, Ivan tells us about difficulties the modern Roma face:

— The problem is that there is no space. Our population grows, children keep being born, and we need more space. There is plenty of space in the village. Those with money have built houses and live there. There is a great need for money as there are many children, and we have sick kids. The villagers don’t care about us. We are few. Once, I’ve even applied to the authorities in Uzhhorod. They said we are too few as well. They said, “When there are many of you, we will be helping you.”

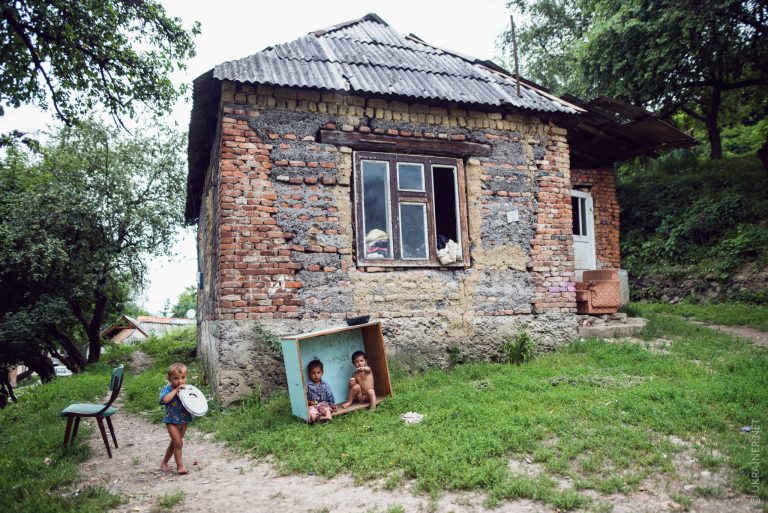

Roma’s houses are noticeable from a distance: they can be recognized by hanging trousers, shirts and linen on the fences. There is a concrete road leading to the wooden shacks over the river on the hill. There are some brick houses here as well. The most luxurious among them is Ivan’s. It is a 50 sq.m house with two rooms, where he lives with his wife, two sons and a daughter. Two elder sons live separately.

On the walls covered with old wallpapers, there are icons and posters with Jesus Christ. A loud crackling and whistle sound belongs to the Dnipro fridge. Ivan kindles a self-made stove — a common heater at Roma houses all over Zakarpattia. Baron’s 6-year-old daughter climbs up on the old soviet sideboard, combs her hair, puts lipstick on her lips and falls over it so much that there is some lipstick on her cheeks as well.

Ivan takes a guitar and plays songs. It is his way of earning money — he plays at weddings. He is tall, solidly built, with a moustache, a beard and long hair. He speaks Ukrainian and Russian. He learnt the languages at the religious seminary, where he received a deacon rank.

Baron

There is no word “baron” in the Roma language. “Baro” is the address to the respectable man who is not necessarily the leader of the community.For 9 years, Ivan has been a local leader, a baron. Now, this position is occupied by his brother:

— I am a newcomer, and my kids were born here. I come from Irshava. I am from an orphan asylum, found my parents here. That’s how I’ve been living by this day. I’ve built the house. The village selected me as a baron. People know me, understand me. My brother was a churchman so now he is selected. Our people gathered, they approved it and so my brother was selected. So now he is our leader. He has the warrant.

Locals do not think well of Ivan, so as of anyone who differs from their average fellow villagers even a bit. But he says that Roma keep no offence about anything:

— We live for the day. As God will take care for tomorrow. We are like you.

The problems of Roma from Dubove village are quite usual: the garbage is not collected, there is no sewage system or convenient logistics. Ivan understands that other villagers do not like when Roma pour out water right on the road, it freezes and the hill turns into skating-rink in winter, while in summer, the dishwater stinks. It keeps getting less free space in the encampment, while the number of kids keeps growing. But they live almost in carton boxes and do not ask for special treatment — just a bit of understanding and support:

— We can’t expect help. We live as God allows us. As we are such people: try to be kind to others, to the neighbours in the first place. Our people can be unkind when someone bullies us. We try to be peaceful and friendly. The other side of the coin: we live here on the road and it happens that the drunk men intentionally try to bully you. They seek causes. You weren’t even close there and he says: you’ve stolen from me. In the last year, nothing like this happened. We can say it was quiet. Now it’s the villagers who steal more. People of our ethnicity are treated with honour now, more like equals, like neighbours.

slideshow

Inaccessible education

The quarter of the polled Roma do not know Ukrainian at all or speak it poorly. The reason is the isolation of the Roma settlements and gaps in education.

This is hardly the issue of Zakarpattia only but of entire Ukraine as well. A great number of Ukrainian Roma have never studied at school and, among those who did attend school, an incomplete secondary education is the most common.

Ivan seems to be not very much disturbed by kids’ education problems. For his son, also called Ivan, he sees a different future:

— They study not very well at school. Ivan always plays musical instruments. He will be a musician for sure.

There is the same problem with education in other small Zakarpattian settlements too. In truth, for the poorest settlements, it is problematic to get access to quality education of all levels. Also, one of the factors is a linguistic barrier: a lot of Hungarian speaking Roma do not know the national languages; their children, if attending school at all, visit either Hungarian schools or non-state educational institutions sponsored by religious communities and Hungarian party. In Mukacheve and Berehove for instance, such schools use only Hungarian language in teaching. The graduates of such schools cannot continue education at Ukrainian higher schools as at the time of graduation they do not speak Ukrainian.

Numbers

1/4 According to the poll of the Revival International Fund in 2015, almost a quarter of the Roma population in Ukraine could not write or read in Ukrainian and every third did it poorly.

slideshow

A local Roma deputy Myroslav Gorvat explains that little Roma attend school until the 6th grade at most and then attend classes more and more seldom. At Uzhhorod school, among 32 students of 9th grade the classes are attended by only 3-5 children. In Myroslav’s opinion, the cause of such low attendance is the lack of motivation:

— Parents don’t understand that they must accompany children to the school, help them get prepared for classes and be ultimately concerned about their kid going to school. The other reason is no free meals except for the junior school, as sometimes children go to school to eat some food.

The Roma’s education often depends on the social status of the family. Even free school education is often unavailable: no money for school supplies, clothes or school renovation fees. Children help their parents to make extra money by keeping the household or looking after the younger brothers and sisters.

However, a child attending school is not a guarantee of quality education. Both the Roma and researchers admit that the educational system of Ukraine does not give much attention to Roma kids. Baron Ivan, sighing heavily, says:

— Our people here are often like this. No one wants to bother with educating them and they themselves cannot adjust to the education they have. There are people who know only how to count. No idea of how to write letters, but the numbers is above all. They had such life, indeed. Kept knocking about the train stations.

Myroslav Gorvat

Now the situation is a bit better thanks to the charity organizations that introduced teacher assistance programs for junior grades where Roma kids study. Also, the centres of conscious parenthood help; they work with illiterate parents.

Roma’s isolation gets stronger right from the first grade as the majority are forced to study at segregated schools. Only the Roma study in such schools and they do not communicate with other local children. Almost every Roma settlement has such a school.

As for higher education, the tendency is slightly improving now. Only those who received higher education at the cost of Roma Educational Fund are almost 500 people, and the number of educated Roma, integrated into Ukrainian society, is even much bigger.

In Zakarpattia, as Myroslav Gorvat points out, 15-20 years ago there was only one Roma with higher education. Today, Roma students and graduates of higher education institutions are at least 50.

Documents and work

Besides education, there are other issues that require a solution. According to the poll of public organizations, 17% of Ukrainian Roma have no IDs, a third of them have no officially registered address. The situation with issuing passports in Zakarpattia is worse than in other regions of Ukraine.

In Mukacheve, for instance, the majority of Roma have no IDs. However, due to the activity of the free assistance centres and the Roma recognizing the importance of having IDs, the situation is improving. Also, childbirth allowances facilitate in passport issue, as they can be received only if having the documents.

As for the employment, 63% of the polled Roma pointed out that they do not work and another 22% work part-time. Among working Roma the self-employment prevails. Over half of the polled ones are occupied in sales or service supply; a quarter more are entrepreneurs.

In Uzhhorod, the Roma work at public utilities as street sweepers, water utility workers and foremen. Those who cannot get employed in Zakarpattia go abroad or to Kyiv. The situation is the same in Mukacheve too.

Who are you and where are you from, Roma?

The problem of the Roma’s origin is still under research. Arguments still continue, and until now it is unknown how and why they have been spread nearly around the whole Europe and how they have managed to protect their identity from the constant globalization waves.

The most common theory nowadays is that the Roma come from India. Notably, “Roma” is their own sole name. However, they are not called “natives of India” in any of the languages. The word “gypsies” is used by Eastern Slavs. This was the name of the heretic sect at the beginning of the second century. Gypsy (English) or gitanos (Spanish) means “Egyptian”. The myth about the Roma’s coming from Egypt was rapidly spreading all over Europe. For example, for quite long the Magyars were calling gypsies fáraók népe, which meant “the pharaoh’s tribe”. However, at the times when the European languages were forming, it was a bit more difficult to verify facts that it is now. Therefore, say, the Frenchmen called the Roma “bohémiens” meaning “Czechs”. It seemed so to them. And until now, the Finns and the Estonians call them simply ‘the dark-skinned”. Notably that now myths say it that Romania is somehow connected with the Roma. The myth appeared because of the similar sounding of these two words.

What the Roma themselves think about their origin and how they single out themselves among other ethnicities, we have decided to ask the Roma themselves:

— You are gadjo! And she is gadjouka! — says Ivan from Dubove, laughing. — In our language, it means a white man and a white woman. We call you this word among us. But we don’t distinguish, it just happens so. Our language came from Sanskrit, and later various regions had their own influence on our language. Also, while going from India, can you imagine how many words we gathered on the way?

In closed Roma communities and small settlements, there is a classic division into “us” and “them”: “RomA” — “gadje” (non-Roma, the stanger).

According to Baron Ivan’s words, the Roma are also distinguished by their way of living:

— We do differentiate between ourselves a bit. There are pavilion gypsies, nomadic and settled. We are considered the settled ones as we live in one place, have built houses here, have families, some kind of a job and we thank God for it. The pavilion gypsies are those who live in a nomadic way until nowadays. They are the women who have their honour and are supposed to wear long skirts. It is a great honour for a husband, a host and a baron himself. There are nomadic ones. The only thing they do is being on the road. Nowadays, all of them crossed over to “metal horses”.

Modern Ukrainian Roma no longer remember the allure of nomadic life their grandparents lived. In 1956 nomadism became illegal. By the decree of the Supreme Council of the USSR “About engaging roguish gypsies into labor”, a nomadic way of life was prohibited. This very day, in spite of this prohibition having been lifted long ago, all Roma settlements in Zakarpattia are settled.

slideshow

The movement of Roma from Zakarpattia to Kyiv or to other cities in warm seasons is called labour migration, as exactly the lack of workplace forces the Roma to migrate. In cities, the Roma create temporary settlements.

In Zakarpattia, small settlements of the Roma exist in a shape of inhabited localities like separate streets, corners or micro-districts. They can be both with a few centuries of history or brand new. The latest ones have been emerging spontaneously, for instance after floods, as the Roma from Zakarpattia were the first to suffer from them — their houses were often situated in the lowland.

Small settlements on the outskirts of localities often have no gutter, sewing system, gas, roads; the buildings can be illegal. Young families often build a small adobe hut next to the father’s with no construction standards taken into account. Legalization of such buildings is almost impossible.

The language that is fading away

Roma of Zakarpattia differ by the language feature as well. There are several coexisting dialects and accents of the Roma language — Romani, and in life, the Roma themselves are not just bilingual but speak three or four languages.

For example, in Mukacheve, Chop and Berehove settlements, the Roma speak Hungarian. Most of them do not understand Ukrainian. In Uzhhorod, there are representatives of several dialect groups living there. There are the Roma-lovari or “ungrika Roma” that speak Lovari dialect of the Romani language, as well as the Servitika Roma, or so-called “Slovak Roma”. In everyday life, both speak fluently Ukrainian, Russian, Hungarian and Slovak.

Baron Ivan from Dubove says:

— We are Ukrainians. Ukrainian gypsies. There are Romanian, Bulgarian, Magyar, Czech gypsies. All live on their own. Often, we can’t even understand each other. We have a different culture. I speak the Romani language poorly. And in different countries, the language is different indeed. I sing songs in our ethnic language. Sometimes, I say some words in it, but mostly — all we have here is Zakarpattian.

Nowadays, Romani is used in everyday life also in Perechyn, Vynohradiv, Velykyi Bereznyi and Svaliava. However, as Myroslav Gorvat points out, it is not enough and Romani is at risk of disappearing. In the Roma settlements, the language develops well. Instead in families living in non-Roma settlements the language is being forgotten despite the attempts to preserve it, though.

The church and alternative education

The life of Ruslan Yankovsky could have been different. He could have lived in poverty, picked up scrap metal or simply gotten drunk. However, he works as a constructor and manages the non-formal education centre in Mukacheve, where little Roma are prepared for the school, taught to play musical instruments and draw pictures, and provided with food every day. All this, according to his words, is thanks to the church.

For many Roma of Zakarpattia, the church is nearly the only place that demonstrates they can have an alternative to the life in poverty in a rough-and-ready constructed tents. Ruslan was brought to the church by his mother when he was six. Now, he is a deacon of the Evangelical Church of Living God, which includes churches in 20 Zakarpattian localities.

According to Ruslan’s words, the church members of Mukacheve church include approximately 400 people. The church members also work with 500 kids and teenagers, for which the non-formal education centre provides a lot of opportunities.

Every day over a hundred children from poor families attend charity church canteen. Some kids practically grow here and become mentors themselves.

— Sometimes we teach simple things: to mind cleanness and hygiene and to respect parents. Sometimes we provide with clothes. If a child doesn’t try something better, he will never know anything else. We give the opportunity to choose. Some families understood the importance of having a shower and made it at home, — tells us Ruslan.

Ruslan Yankovsky

The church tries to make education popular and encourage to not give up studying. The church members teach little Roma to read and write in Hungarian. There is a computer class here, as well as a sports school.

Older Roma are provided with vocational training here — they can master the professions of constructor or welder. This is where Ruslan was studying.

— The church plays a great part in the life of the Roma population. It has changed the attitude of other ethnicities to the Roma. Until this, there was a huge tension — the Ukrainians were afraid to visit encampments. Now, the Ukrainians visit our church, pass through the encampment and we arrange joint events, — says Ruslan.

The pastors become the more important figures in the life of the Roma community, which they also represent.

The public activist Iryna Mironyuk thinks that in modern conditions the pastors compete for the authority with barons the meaning of which transforms. This process in Zakarpattia is rapid, — Gorvat mentions.

In Myroslav’s opinion, the barons are populist leaders unable to fulfil functions necessary for the Roma communities. In most settlements, the baron’s status has already lost its importance and has been replaced by leaders, deputies, heads of public organizations and pastors.

Ruslan himself considers that pastors should not be idealized either. So to say, not every among them has the authority. In Mukacheve, the church has but the stronger influence, as in the past there were no good barons to represent the community:

— For us, the church is not a building people visit once a week. We want it to be involved in various areas of life, — summarizes Yankovsky.

Korolevo. From a shack to the palace

Small Roma settlements in Zakarpattia can largely differ in their living conditions. For instance, Uzhhorod settlement is not as isolated as the Mukacheve’s, where there is no access to potable water.

— Svaliava encampment, where about two thousand Roma live, is the history of success. Baron Matviy Balint has been a deputy for over 10 years now. He became a civil servant to protect the interests of his people. He has lain on water supply to the settlement, has built houses for youth, all children of the settlement attend school and learn Ukrainian, — says Iryna.

Possibly, the most populated Roma encampment in Eastern Europe is the Mukacheve’s with 4-10 thousand people living there. In Mukacheve and Berehove, there are nearly the worst living conditions.

The financial situation of the settlements differs depending on the community’s priorities. Mukacheve and Uzhhorod Roma have been occupied with art professions (first of all, music) since ancient times, and in Vynohradiv district they’ve been involved in manual labour and going for the seasonal jobs.

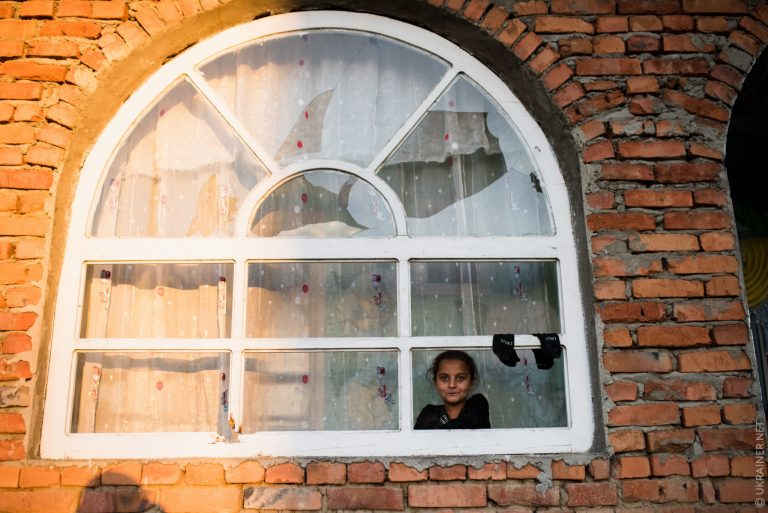

One of the wealthiest and equipped Roma encampments is the settlement in Korolevo, Vynohradiv district. The houses here are made of brick, some even with many floors. The road is shriveled with gravel. Outside, there are tidy children running about. The girls wear traditional Roma dresses. The women pay much attention to dressing, in such way emphasizing their status. Metal threads and laces on the skirts are supplemented with gilding; the clothes are decorated with artificial stones. Family jewelries, usually made on request, may include precious stones. They become a dowry for the bride as a symbol of wealth of the family she comes from.

Although the settlement in Korolevo is quite wealthy, it is much inferior to Slovak and Romanian lines, which compete in demonstration of welfare and precious jewelries.

In the settlement of Korolevo, there are 3700 people living there. Baron Lotsi tells us that most of the local Romas earn money in Russia and points out: no criminality.

Men from Korolevo work in teams usually consisting of close relatives and neighbours. They often manufacture can elements for roofs, drains etc. The masters here have a longstanding reputation and their own style of decorating products. Financial security, though, does not guarantee the absence of the problems that exist in other settlements. Some people here still have no documents; there are a lot of illiterate people:

— There are a lot of problems with gypsies. The biggest is that they are uneducated. They are not taught appropriately, don’t go to school. You see, one was attending school but wasn’t taught the same as others there. Attitude is different, less attention, — says baron.

The problems could have been avoided if the Roma had lived with the Ukrainians, considers Lotsi. So to say, the Roma living alongside with other ethnicities would have been cared about more.

We are the Roma and not gypsies!

It seemed that in the last compartment of the train “Uzhhorod-Kyiv” the radio song was playing, but no — that were four men playing and singing live. The train arrived in Chop. The people who had got on the train sat at once in an empty neighbouring compartment to listen. Most songs were about Jesus and faith, they sounded very tuneful. They were playing a full set for half an hour and, yet afterwards the improvised concert, talking about their life in village of Serednie, Uzhhorod district.

By Ukrainian passports they are Victor, Yosyp and Vitalii but in Roma settlement they were known as Ityu, Jijyu and Duchu. Ityu and Duchu are the Roma nicknames, while the nickname Jijyu comes from the name of Ukrainian singer. Ityu is 37 years old; he has a daughter and four grandchildren. Thirty-year-old Duchu has seven kids, and 21-year-old Jijyu — already four.

Iryna Mironyuk

— Why do we have so many children? Oh, cause there is no electricity in many of our houses, — they are joking.

On average, there are about three thousand Roma living in the Roma settlement. Now, they have their own school. For the last 15 years, as boys say, there were a lot of positive changes. They say that they themselves would like to study, but the community has been encouraging not a very honest way of earning money, and studying itself was not popular, though.

— I have been attending school for two years now, — says Duchu. He is thirty but he is not ashamed of having started to learn how to write just now. — I couldn’t read at all. My first book was the Bible. I’ve been carrying it with me and saying “It’s written so in Bible”, but I couldn’t read it.

Jijyu and Ityu are Baptists and Duchu is an Evangelist but they do not argue. Each of them quotes the Bible from time to time and likes talking about his way to God. Ityu says that everyone in the village can count, while very few are able to read and write. Officials profit from the Roma’s illiteracy and demand bribes.

In the past, local Romas travelled around Soviet Union, leading a nomadic life, now they have settled.

— We pray to God that he forgives us for how we lived before, — says Ityu.

Duchu recalls how they were getting on the train to Chernivtsi. People were going from the market with identical bags. The boys were stealing the unattended ones:

— Back at that time, you could not prove it was yours! Everyone had the same, and we were a full compartment of people, no one would be coming for the bag. Once, I was stealing a bag, I picked it up and it was so heavy. I thought: woo, boy, I am busted! I took it into the water closet, opened it up and there were wine bottles. I left some there and took the rest, — recalls Duchu.

Jijyu is the youngest and jokes the most. They all are full of self-criticism and make fun of themselves:

— I am a “hromadianyn” (from Ukrainian “citizen”) of Ukraine! We are Ukrainians! — says Ityu.

— You’re not a “hromadianyn”, — Jijyu laughs at him, — you are Romadianyn (i.e. Roma citizen, play of words)!

Although they sometimes call themselves gypsies, this word they bluntly reject. They say the first association is a thief:

— We are Romas, not gypsies! You do like when you are called Ukrainians and when, for instance, “khokly” — you don’t. Or when the Russians call you “bandery”! For us, it is the same here.

— We are seldom asked about anything by anybody. We can tell a lot but people can only think that we will be stealing something, — says Duchu.

This story, the same as the story of Baron Ivan and Deacon Ruslan, is about transformation and stereotypes. About how Roma differ from gypsies from the concept of the Romas themselves. About how the Roma community aspires for changes and as a result does change. Also, each of these stories is about how the Roma live alongside with the ethnical Ukrainians. About how contrasting the culture, language and the life of Ukrainian Roma can be, which they managed to preserve despite everything.

How we were shooting

On our way to the Roma settlement in Korolevo we also dropped by to the Ukrainian family who has been living there for over 60 years now and has its own not less interesting story. Watch this and about wealthy Roma of Korolevo in our video blog.