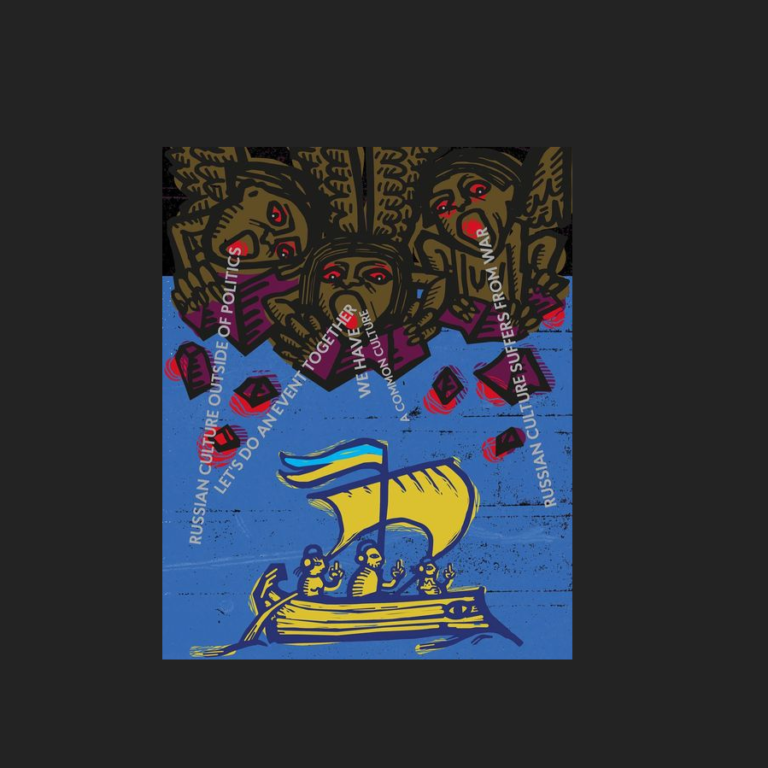

Russia has been honing soft power tools for years. And did it successfully in different countries, not only in Ukraine. Russia is using every means to push and maintain its chauvinistic, imperial narratives in the world. Russia’s cultural expansion has often been a precondition for territorial expansion, military pressure, and terror.

SOFT POWER

The ability of the state to achieve its goals through the attractiveness of its own culture and socio-political values in contrast to the "brutal force" based on military and economic pressure. This concept was first formulated by Joseph Jr., a professor at the John F. Kennedy Harvard Institute of Public Administration.Cultural expansion is always Russia’s first step in its quest to conquer the territory of any country. And if it is opposed by civil society, then it uses weapons. The transition to this second step is only a matter of time.

On the example of several countries we’ll show you how it works.

Belarus

Way of influence:

In the country of “Europe’s last dictatorship”, Russia managed to establish the narrative that the prosperity of Belarus as a state would be impossible without the support of Russia and a common past within the USSR.

The result of the influence:

Total Russification has in fact endangered the Belarusian language.

Belarusian language clubs are the first to be suspected of anti-government actions, and their members, who are not afraid to speak out about their national identity, are often the first to be detained at rallies.

Any cultural opposition is brutally suppressed, so it goes underground or operates abroad.

“Cultural” life in Belarus is completely monopolized and controlled by the Belarusian authorities. There is a whole list of Belarusian artists who cannot perform in their country due to “wrong” positions and cultural narratives.

Photo: Musa Sadulayev for AP

Georgia

Way of influence:

In politically polarized Georgia, Russia has acted according to its classic “soft occupation” scenario: educational programs to russify Georgians, incite ethnic hatred, and distract from the European course of development.

As in Belarus, in Georgia, Russia has asserted the myth of “centuries-old” cultural and religious ties between the two countries.

The result of the influence:

In 2008, the Russian Federation, with the support of separatist groups, wanted to “restore constitutional order” in Georgia. The result was war and 20% of the country was occupied.

In Georgia, there is a special fund “Russian World”, funded by the state budget of the Russian Federation, with propaganda media, and the Orthodox Church is a stronghold of the existing regime and a lever of influence on the older generation. Despite the fact that the Georgian Orthodox Church is formally independent of the Russian Orthodox Church, in reality, it is almost entirely run by Moscow.

In 2017, Georgia for the first time officially recognized Russia’s “soft power” as a threat to the country’s territorial and cultural integrity.

Kazakhstan

Way of influence:

Kazakhstan is a country that is significantly influenced not only by Russia but also by China, another large empire that encroaches on certain areas of Kazakhstan, considering them historically their own.

For Kazakhs, Russia is a carrier of Western culture, meaning only through Russia one can see manifestations of democracy because, as the other neighbour they have communist China. Therefore, for Kazakhs to be equal to Russians means to be equal to the “west”.

It was Russian security forces who came to the aid of the dictatorial authorities in Kazakhstan during the protests in January 2022. Russia then “helped democracy” through a common context, citing “pro-Ukrainian (Maidan) influences”, supposedly present among citizens, that were actually standing for their rights at the squares of Almaty, Shymkent, Astana, etc.

The result of the influence:

Kazakhstan is currently ruled by a brutal dictatorship. The special services control everything, including culture. At the same time, the authoritarian government, in contrast to the Belarusian government, is trying to revive the national culture. The strengthening of the role of the Kazakh language, the renaming of cities or the transition to the Latin alphabet are accompanied by sharp statements by the Russian Federation, including direct threats to the territorial integrity of Kazakhstan.

Russian television propaganda operates freely in Kazakhstan. About 20% of the country’s population are ethnic Russians, living compactly in the northern and eastern regions of the country. Most of the Russian-speaking population in Russia’s cultural and information space supports Russia’s war against Ukraine. The pro-Ukrainian position is mostly held by Kazakh-speaking citizens. State propaganda adheres to neutrality, calling the war a “Russian-Ukrainian crisis.”

Germany

Way of influence:

There is still a total misunderstanding among Germans that German Nazism was defeated not by Russians but by all citizens of the USSR, primarily Ukrainians. Ukraine suffered the most from the Nazis – more than 9 million people died (about 4 million of whom were military and the rest were civilians). More than 700 cities and about 28,000 villages were damaged and destroyed.

During World War II, more than 6 million Ukrainians fought in the Red Army, and more than 100,000 were members of the UPA, which actually fought on two fronts – against the Nazis and against the Communists.

Instead, Vlasov’s Russian Nazi army fought on Hitler’s side from the moment of its creation until its destruction under the Russian tricolour and St. George’s ribbon (symbols of modern Russian neo-Nazism – Putin’s rashism). It turns out that, in fact, during World War II, an insane number of Russians fought on the side of the Nazis.

The result of the influence:

Since World War II, Germans have had a guilt complex before the Russians. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, relations between Germany and Russia were actively developing. Germany also has a large Russian-speaking community of 3.5 million people. These are ethnic Russians, as well as Germans, Jews who moved from different republics of the USSR.

Germany has helped establish Russia’s ties with the West and has become a key economic and trade partner. All this changed the attitude of the Germans to Russia as an enemy. By 2012, relations between Russia and Germany were gradually developing. They have become much cooler since Putin returned to power and his efforts to minimize foreign influence inside Russia, including Germany.

However, Russia still has a strong cultural influence on the Russian diaspora in Germany. In particular, using social networks, where they successfully disperse propaganda messages.

In 2016, Russia used the fabricated “Lisa case” for propaganda purposes. Russian media dispersed news of the abduction and rape by Arabs migrants of a 13-year-old girl from a Russian family living in Berlin. The purpose of the fake news was to discredit Germany in the eyes of other European countries and destabilize the then German political force.

Representatives of the Alternative for Germany party continued to develop cultural ties with Russia, which in turn increased its visibility by using its usual propaganda tools.

Most Russian-speaking Germans watch Russian propaganda channels, succumbing to anti-European Kremlin narratives.

The result of the influence:

During the full-scale war between Russia and Ukraine, it was the German PEN Club that did not support the boycott of Russian culture. The president of the German PEN Club, Denise Eugel, argued: “The enemy is Putin, not Pushkin, Tolstoy or Akhmatova.”

PEN CLUB

An international non-governmental organization uniting professional writers, editors and translators. Founded in 1921.This position, based on the phrases “no to war” and “we are for peace”, is short-sighted, because Russia uses culture as one of the easiest ways to root its cultural code.

So far, Germany has not supported Ukraine’s accession to NATO, and with the start of a full-scale Russian invasion, it has long refused to provide weapons to Ukraine. Another result of the impact is Germany’s energy dependence on Russia, which the latter seeks to strengthen in every possible way. Russia also takes advantage of Germany’s reluctance to resolve global military conflicts.

The head of the German community in Crimea (up to 2,000 people), who took a pro-Kremlin position in 2014, today advocates the lifting of sanctions against Russia and the recognition of the Crimean peninsula as part of Russia.

France

Way of influence:

Diplomatic relations between Russia and France are over 300 years old. There was a strong cultural exchange in the XVIII century when French artists emigrated to Russia, which actively absorbed all available European cultural experiences. In the XIX century, after the defeat of Napoleon, Russia began to form a myth about itself as an invincible country.

Soviet state organizations operating in France and Russia instilled Soviet ideology instead of cultural exchange. The USSR did everything to stop French from being the language of the Russian cultural elite, even though it was studied at school.

At the time, Russia pushed three key narratives into France: anti-immigration, anti-Americanism, and anti-liberalism. Some of them are still more or less nourishing.

However, the French still unequivocally glorify Russian literature, ballet, painting and language. This allowed the Russian authorities in the 90s of the twentieth century to launch special programs for the return (literally or mentally) of their “compatriots” or French citizens attached to Russian culture.

The result of the influence:

Despite the fact that there are opposition groups in the French community of Russian origin, Russia has managed to ideologically unite the diasporas, although most of them ended up there for political reasons. As a result, a number of descendants of the Russian aristocracy still run important cultural and religious institutions in France, promoting Russian imperatives in the European country.

Ukraine

Way of influence:

Russia’s cultural ties with Ukraine date back to Kievan Rus. This is where the Russian Empire originated and it is until then that modern Russia appeals to the “historical cradle” and “brotherhood”. In the XVIII century tsar’s Russia sought to take over everything Ukrainian. The apogee of cultural conquest took place during the Soviet era.

With independence, Ukraine has finally taken a pro-European course of development. However, Russia has always carried out cultural intervention on our territory.

Literature, music, theatre, cinema – in these areas, Russia pushed the Ukrainian language and instilled a complex of inferiority.

Putin and his allies used culture as an instrument of mental occupation. For years, they have argued that Ukrainians are not a separate nation with more than a thousand years of history, but Russians who need to be liberated.

The result of the influence:

Ukrainian youth actually grew up on Russian music and movies, becoming susceptible to their narratives. The results of the national annual monitoring survey show that until 2014, most Ukrainians supported the idea of two official languages – Ukrainian and Russian, and were ready to join the hypothetical union of Ukraine, Belarus and Russia.

Russia has funded some of the political parties and media that supported it.

The lack of Ukrainian cultural influence in Crimea facilitated Russia’s annexation in 2014.

Photo: Alex Lourie

The Russian language still remains a key instrument of cultural and political manipulation of the Russian Federation. The Putin regime, declaring oppression of the rights of Russian-speaking Ukrainians, calls for their “liberation.” There is a certain pattern – in those regions of Ukraine where the Russian language dominates, during the presidential or parliamentary elections, people more often chose politicians who lobbied for Russian narratives.