For centuries, Ukrainians have had their unique Ukrainian language and culture. These developed separately from Russian society, in a parallel tradition. However, when the Ukrainian territories were incorporated into the Russian Empire and then the Soviet Union, the Russian authorities imposed their own language as “higher”, “more prevalent”, and “the right” language to use. Russia’s autocratic officials have always sought to devalue, diminish, and deny the existence of the Ukrainian people and their achievements, consistently banning the Ukrainian language, education, and arts, as well as spreading numerous myths about “spiritual unity with Russia”, the “brotherhood of nations”, and urging “a complete return under Moscow’s influence”.

Myths about the “Russianness” of the east of Ukraine still circulate in the public sphere. In particular, there is one implying that the Donbas region “has always been feeding the entire Ukrainian nation” while this mining and industry region has in fact experienced heavy dependence, having been subsidised by the state. And the core narrative tries to convince us that these lands have always been part of Russia. In fact, these are only Russian propaganda statements that have no objective historical basis. In this article, we explore how the aggressor country has striven to Russify the east of Ukraine, and how they continue to do so today.

Russification

A combination of informational, cultural, academic, diplomatic, military, and general social trends, aimed at forcing the transition to the Russian language and the reproduction of Russian imperial myths, customs, and world views. It is also a set of aggressive and concealed actions, narratives, and environments aimed at strengthening Russian autocratic national and political superiority in countries that are part of the Russian Federation and/or are affected by its colonial policies.All Russian-created narratives about the east of Ukraine have the same goal: to divide Ukrainians and justify the war that began in 2014 and entered its full-scale phase in 2022. These narratives help Russian propagandists to deeply root and reinforce the idea of Russians and Ukrainians being “one people”. Myths like this did not appear out of thin air. Russia has been implementing aggressive policies towards this region for centuries, erasing its identity and/or physically destroying the local population. These policies have been enacted using instruments such as deportations, genocides, passportisation (the mass issuing of Russian passports), and even forced language introduction. And this is only a fragment of a grand plan for the Russification of the east of Ukraine, where the ultimate goal is the ideological, mental, and literal conquest of the region.

Because Russia invests millions in its media propaganda around the world, and because the world has an inert tolerance for the Russian Empire and its rhetoric, these myths continue to have a harmful effect on the international community. Being a master of fakes and manipulation, Russia strengthens its aggressive positions and misleads thousands of people around the world. Thus, the loyalty of the global public plays into Russia’s hands where geopolitics is concerned.

Imperialism in words

Russian propaganda starts at the conceptual level. Even by simply calling the territories in the east of Ukraine “Donbas”, we are ignorantly using the product of Russian myths.

To start with, let’s investigate the origin of the name “Donbas”. Unfortunately, it has taken deep root not only in the everyday parlance of Ukrainians, but also in the vocabulary of the media. By using the name “Donbas”, Russia designates the territory of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, singles it out, and sets up the rest of Ukraine as foreign and in opposition to it. This method helps to reinforce manipulative stories about the “civil war in Donbas”.

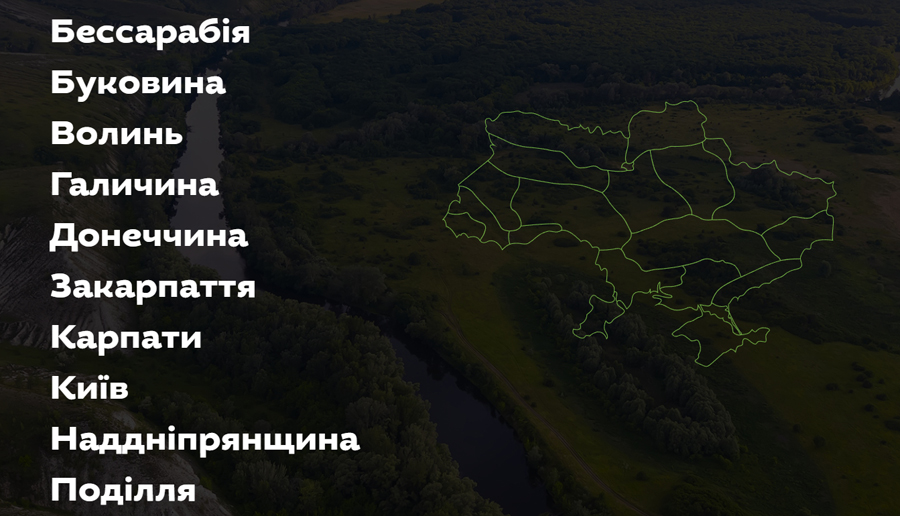

In fact, the term “Donbas” is not particularly accurate if we are talking about the historical region of Ukraine, since it is a toponym given to the Donetsk coal basin, an area rich in mineral resources. Its definition is exclusively a geological one. Instead, it is appropriate to speak of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. On the Ukraїner map, these two regions are part of the historical and geographical region of Donechchyna. The name “Donetsk” comes from the Siverskyi Donets river, as most of the region is located within its basin.

There are also ongoing discussions in Ukrainian society as to whether the names “eastern Ukraine”/”the east of Ukraine” (and their counterparts “western Ukraine”/”the west of Ukraine”) are appropriate. When it comes to standard language usage, their use to denote parts of a state or region is quite normative. However, for instance, the Centre for Countering Disinformation (a part of Ukraine’s National Security and Defence Council) recommends using the terms “east of Ukraine” and “west of Ukraine” instead of “Eastern Ukraine” and “Western Ukraine”, which are “artificially created toponyms with which Russian propagandists try to expand the territorial perception of the war” .

For some people, references to “Eastern” and “Western” Ukraine also spark associations with divided countries: for instance, North and South Korea or West and East Germany. In these phrases, the adjective seems to mark off a particular territory, while the noun, on the contrary, emphasises that it is part of the whole. Even in the language we use, it is crucial to indicate that Ukraine is indivisible. All these territories constitute a unitary state which has been struggling to win and defend its independence for centuries. Ultimately, neither “eastern Ukraine” nor “the east of Ukraine” has generally recognised borders, so these concepts are not functional enough to have any official weight. To define the territories more clearly, it is better to use either the regions’ official administrative names, or else their historical and ethnocultural names, such as Slobozhanshchyna or Pryazovia.

Looting the past

Over the centuries, especially since the beginning of the 16th century, certain ideas have been (and continue to be) hammered into people’s heads: that the Russian state and the Russian people originate from the Grand Principality of Kyiv; that Kyivan Rus is the cradle of three fraternal peoples (Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians); and that Russians are the rightful heirs of Kyivan Rus under the law of “senior brotherhood”. This altered narrative is still used in Russian historiography and by Russian statesmen. However, during the existence of the state of Kyivan Rus, there was no mention of the Muscovite state. It is known that the Moscow principality, as an ulu of the Golden Horde, was founded by Khan Mengu-Timur only in 1277. By this time, Kyivan Rus had already been developing for more than 300 years.

Nonetheless, the imperial mindset still does not allow Russians to admit that their power is derived from the ordinary Tatar-Mongol nobility. Thus, on 22 October 1721, Tsar Peter I proclaimed the kingdom of Moscow the “Russian Empire”, and the Muscovites “Russians”. This “rebranding” was based purely on imperial hubris and the ambition to make a false historical narrative into a recognised one. This change in the name of the Muscovite state posed a serious challenge to the identity of the Ukrainian people.

After Peter I, who turned Muscovy into the Russian state, the elite of Muscovy began to think about the need to create a coherent history for their own state. Empress Catherine II (1762–1796) took meticulous care of this matter. Having familiarised herself with archival primary sources, she pointed out the fact that the entire history of the state was based on verbal mythology and had no basis in evidence.

So, by her decree of December 4, 1783, Catherine II created the “Commission for compiling notes on ancient history, mainly of Russia”. The chief task set before the commission was to substantiate the “legality” of Muscovy’s appropriation of the historical heritage of Kyivan Rus, and to generate a historical mythology of the Russian state by reworking the annals and writing new annals, among other falsifications. The commission operated for 10 years. On the empress’s instructions, they conducted a revision of all the ancient primary sources. Some sources were corrected, others were rewritten, and those in the third category – any evidence that posed a threat to the empire – were destroyed. Thus, a “convenient” history was rewritten, and Russia allegedly received carte blanche to “bring originally Russian lands back together”.

At the end of the 17th century, the territory of left-bank Ukraine, with Kyiv and Zaporizhzhia, came under the power of the Muscovite state. It happened in accordance with the Treaty of Andrusiv, a separate truce that violated the terms of the Pereyaslav Rada (1654) and other treaties with the hetmans (in particular, with Bohdan Khmelnytskyi). Notwithstanding the earlier agreements, local political will, and the intentions of Ukrainian public figures, this treaty established the violent division of the Ukrainian ethnic territory into two parts: Right-bank Ukraine and Left-bank Ukraine. This partition was cemented by the so-called Eternal Peace in 1686.

Kozak Hetmanate

A Ukrainian Kozak state in the region of what is today Central Ukraine between 1648 and 1764. Its leader was called Hetman who was elected democratically.The Kozaks remained the driving force behind the national movement for freedom. The strengthening of the economic independence of Zaporizhzhia and the enormous influence of the Zaporizhzhians on the development of the Ukrainian people’s political consciousness posed a potential threat to the Russian Empire’s colonial policy in the south of Ukraine. The Zaporizhian Sich – a semi-autonomous Kozak polity – was the centre of the Ukrainian identity that formed, with democratic traditions and military self-government. This is why it cast a shadow of danger to the expansionist apparatus of the Russian Empire. In 1709, as a result of a punitive expedition, Muscovite troops destroyed a number of Kozak towns and completely destroyed the Chortomlytska Sich. The previous year had seen the Baturyn massacre: a punitive campaign by Moscow’s troops to capture and destroy Baturyn, the Hetmanate capital and the residence of Ivan Mazepa. During this campaign, the Muscovite troops slaughtered all the inhabitants of the city, regardless of age and gender. According to various estimates, between 12,000 and 15,000 local residents were murdered. The city itself was looted, including the Orthodox churches; then, on General Menshikov’s orders, the city was burned down and the churches destroyed.

Ivan Mazepa (1639-1709)

A prominent Ukrainian military and political figure, statesman, and philanthropist. Hetman's mace, a Kozak symbol of power, belonged to him for almost 22 years. Under his rule, Hetmanate experienced significant economic growth, the stabilisation of the social tensions, and rise of church culture, education, and Barocco architecture.Moving forward, the defeat of the Ukrainian national liberation struggle of 1917-1921 led to the liquidation of national statehood and another change in the political and administrative structure of Ukrainian lands in the 1920s and 30s. In the interwar period, ethnic Ukrainian territories were part of four states: the USSR, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Romania. Later, the military and political events of the Second World War led to a new change in the administrative and territorial structure of Ukrainian lands. According to the secret articles of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, in September 1939, the Red Army occupied the territory of western Ukraine, and in June 1940, northern Bukovyna, Khotyn, Akkerman, and the Izmail districts of Bessarabia, which were soon annexed to the Ukrainian SSR (on 2 August 1940). This is how the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic emerged, which existed under the Russian Soviet occupation until 1991, when it gained complete and internationally recognised independence from Moscow for the first time in history.

And yet, the Russian Federation has its own distinct view of the situation. This is why, in 2014, they launched an unlawful military invasion of Ukraine.

De-Ukrainisation of culture and life

The metaphor of the “Prison of the Peoples” can be traced back to the era of the Russian Empire. For every people within the empire from Kyrgyz to Armenians and from Yakuts to Turkmen, it is self-evident that Russia is always an oppressor. All these peoples have their national heroes: fighters for freedom of speech, insurgents against the occupation, and advocates for justice and humanism opposing the Russian criminal regime. Ukrainians know their history and are very conscious of the exterminations, prohibitions, and humiliations Moscow inflicted on them in the 19th century and even earlier. Moscow also introduced numerous linguicidal rulings: the disbanding of the Saints Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood, the Valuev Circular stating that “a separate Little Russian [a degrading way of referring to Ukrainian] language never existed, does not exist, and shall not exist”, and the Ems decree passed by Alexander II, which prohibited the printing and importation from abroad of any Ukrainian-language literature, as well as banning Ukrainian stage performances.

Printing books in Ukrainian was prohibited, and primers in Ukrainian were confiscated from church services and schools. These processes began at the end of the 17th century, to varying degrees of intensity and success, but covered almost the entirety of modern Ukrainian territory situated on the left bank of the Dnipro. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Romania, and Austria-Hungary also used the tools of assimilation, so Ukrainians everywhere suffered from having to live in statelessness. However, the Muscovite kingdom’s language policy was particularly brutal and intense, leaving an irreparable mark on the eastern territories of modern Ukraine. The Ukrainian language was not in demand, whether in state administration, education, or publishing. Moreover, as a result of these repeated persecutions, the language did not develop. For a significant part of Ukraine’s administrative and cultural elite, Russian became, if not their native language, then at least one that provided access to power and made a career possible. At home, Ukrainian speakers were harassed and insulted. Russians and time-servers would call the Ukrainian language a “savage dialect”, “uneducated slang”, a “South Russian peasant fiction” and other derogatory names. At the official level, it was forbidden to teach, write, or speak publicly in Ukrainian. Any publication in Ukrainian was confiscated: magazines, brochures, poetry collections, even the Bible.

Ukrainians had a free-spirited vision of the future, fought for a national uprising, and opposed the Russian Bolshevik occupation. Still, the war against Moscow was lost in 1921. The Bolshevik army inflicted brutal policies of requisition on the people, and the Soviet government moved the capital from Kyiv to Kharkiv for more than a decade to dispel any possible opposition, cut off the national ambitions of Ukrainians, and construct a new myth for the outside world and their own internal propaganda.

The historical phenomenon known as Ukrainisation of the 1920s and 1930s was the policy of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, aimed at neutralising the national liberation aspirations of the Ukrainian people and strengthening Bolshevik power in the USSR. It provided for the use of national personnel in Soviet, party and public institutions and organisations, the expansion of the ideological influence of the Communist Party on Ukrainian society through the use of the Ukrainian language, and the promotion of “proletarian elements” in national culture. While controversial and risky, Lenin’s national policy became the field of trust for revolutionary art and the study of national identity among Ukrainian artists and researchers. Tragically, they were doomed to become the Executed Renaissance. Talented writers, philosophers, poets, scholars, musicians, designers, and theatre professionals were among those visionaries who were creating outstanding works of art and launching important public discussions. The Soviet authorities brought this period to an end with mass repressions. Mykola Khvylovyi, Mykhailo Semenko, Vasyl Yermilov, Les Kurbas, and others were arrested and then shot or sent to labour camps to die from corporal punishment, freezing, and exhaustion. The entire literary and artistic generation of the 1920s and 30s suffered from this brutal slaughter at the hands of the communist regime for being free thinkers and standing for truth.

During the Soviet era, there was also a new approach to the Ukrainian language. Russia did not just ban the language – it did everything in its power to make Russian prestigious, so that people would choose it of their own accord. Russian was taught in universities and acquired the status of the language of the city and the intelligentsia. It was easier for Russian speakers to move up the career ladder. Therefore, people often either gave up Ukrainian themselves, or did everything to make their children give it up. Ukrainians still feel the consequences of this. The Russian policy of language assimilation was so successful that to this day, a large proportion of modern Ukrainians can still consider Russian their native language. However, in fact, this was most likely a choice forced upon their ancestors, the alternative to which was physical destruction.

The fact that a person is Russian-speaking does not mean that he or she is ethnically Russian. All the former Soviet republics know only one common language. Contrary to its own promotional rhetoric, the USSR was not a union of equal republics with equal opportunities:one country and one culture had better conditions than the others. And somehow, it turns out that this country was always Russia. The Russian Federation seeks to restore its position of regional hegemony by all means possible and unimaginable. Russian leaders claim that if people in another country speak Russian, they belong to Moscow. However, Ukraine has consistently chosen a different vector of development: during the Orange Revolution in 2004, then the Revolution of Dignity in 2014, and now, resisting the Russian invasion. Since 2014, Russian-speaking Ukrainians have been defending Ukraine’s borders, volunteering, and doing everything possible to resist the aggression of the Russian Federation. This year, many of them have finally made the switch to Ukrainian, which can be especially difficult for older people who have been communicating in Russian all their lives. However, the crucial issue lies precisely in the fact that the Russians do not need an excuse to destroy Ukraine.

Let’s recall Holodomor, one of the biggest crimes against humanity in world history. As a result of Soviet policy in Ukraine in 1932–1933, millions of people were killed. Ukrainians were starved to death for their nationality, language, identity, and their refusal to follow the communist totalitarian machine, which forcibly led people towards the illusory bright future of communism achieved through blood and torture.

By 18 November 1932, Vyacheslav Molotov, a leading figure in the Soviet government and Stalin’s accomplice, had introduced “black lists”, or so-called “black boards”. If any village made it onto one of these lists, it would be surrounded by army units, who would block entry into and exit from the village, remove all essential goods from shops (such as salt, matches, and paraffin), and confiscate any food. In other words, it was a siege in which people would slowly starve to death. The only territories where this regime was introduced were Ukraine and Kuban, territories mostly populated by Ukrainians. Nothing like this was done to any other administrative region or Soviet Republic.

The existence of the USSR as a geopolitical project, involving artificial ideology and bloodthirsty methods, has become one of the greatest tragedies of the 20th century. hey targeted to eliminate the entire social groups in Ukraine and dozens of other oppressed nations, including party and government officials, clergy, intellectuals, and wealthy peasants. The repression consisted of persecution on suspicion of “counter-revolutionary activities”, “espionage” or “anti-Soviet agitation”; persecution of the kurkuls (who prevented the “nationalisation of property”); and deportation to other regions of the USSR. Place names such as Katyn, Solovki, Sandarmokh, Norilsk, Vorkuta, Kengir, Butugychag, Kolyma, and Dmitrov, have become synonyms for suffering for entire generations across the continent.

Kurkul

A derogatory name for a wealthy peasant or anyone who simply opposed the Soviet policy of collectivisation.All these Russian practices – arrests, censorship, denial of the crimes committed, and inaccessible archives – resulted in the erasing of national identity and collective memory, brutally preventing anyone from reviving and reflecting on these stories. Ukrainians were terrorised and made to believe they could only survive if they “stayed quiet and kept a low profile”. For many people, this meant switching to the Russian language, accepting Russia’s historiography and brutal policies, and giving up their own origins and values. This is how Russia used propaganda to lay the foundations for the first hybrid war and later technological war. They made it possible to talk about the east of Ukraine as a part of Russia and the alleged “oppression” of Russian speakers. In fact, the “Russianness” of this region is the result of centuries of systematic Russification. And most importantly, modern Russia continues to conduct this policy in Ukrainian territories temporarily under its control. At the first opportunity, the occupiers remove Ukrainian-language signs, damage and dismantle historical monuments, remove Ukrainian-language books from libraries, and destroy school textbooks.

Russian settler colonialism

The resettlement of its citizens is a notorious Russian practice in all the territories occupied by Russia, not only the Ukrainian ones. The authorities of the Russian Federation try to erase the physical and mental borders between its own citizens and those of the colonised nations, in order to simulate a storyline about “one people”. For instance, Russian army officers have always been encouraged to move to Crimea; they received prestigious free apartments for their families. For Russia, this was an attempt to legitimise its military presence in the occupied Ukrainian peninsula.

Historically, this practice became widespread as early as the 16th century. At that time, the Hetmanate was a Ukrainian Kozak state that had political and economic autonomy and actively traded with the west. The Kozaks had their zymivnyky (winter shelters – ed.) in the area that would later be known as Slobozhanshchyna. The Russians began to “master” the territory that formally belonged to the Muscovite State.

Zymivnyky (Ukr. “Winter shelters”)

Small settlements where the Kozaks spent the winter. They originally appeared in the first half of the 16th century as places to keep livestock in winter.The 16th and 17th centuries saw the creation of the Belgorod Cherta, a line of fortifications to protect the southern border of Muscovy. It was a series of fortress cities, defensive points on roads, and fortifications in field and forest areas. Fortresses were built, in particular, in places already inhabited by Kozaks, and border detachments were forcefully staffed with Ukrainian Kozaks and peasants and Russian soldiers, in particular from the northern regions.

Slobozhanshchyna

A historical geographical region in northeastern Ukraine that corresponds closely to the area of the following Kozak regiments: Ostrohozk regiment, Izium regiment, Kharkiv regiment, Okhtyrka regiment, and Sumy regiment. Its name, derived from the sloboda settlements founded there, came into use in the early 17th century and continued until the early 19th century.The next stage of settlement by Russians began after the defeat of Ivan Mazepa by Peter I in the Battle of Poltava. In the 18th century, according to the history professor Yaroslav Dashkevych, the confiscated estates of Mazepa’s officers passed mainly to Russian landowners, who also brought their serfs there. Russian merchants actively settled there, since the Russian Empire was gradually supplanting Ukrainian competitors. The Hetmanate was forbidden to trade directly with Western Europe and a Russian monopoly on the sale of most goods was introduced, while the import of factory products was prohibited.

After the forcible destruction of the Zaporizhian Sich in 1775, and the complete abolition of the Hetmanate’s autonomy in 1783, many Russians – including officials, soldiers, landowners, merchants and artisans – moved to Ukrainian lands. The settlers also included fugitive Russians, such as serfs and military deserters, who were protected by the administration due to its interest in the accelerated settlement of these lands.

It is remarkable that Ukrainians predominated in the south-eastern region. For example, in the Katerynoslav and Kherson provinces (created in 1802), as of 1851, the population was 70% Ukrainian (703,699 people) and 3% Russian (30,000 people). At the end of the 19th century, centres of heavy industry began to develop in the Donetsk Basin, the Dnipro Industrial District, and Kharkiv. This kind of production meant that these territories were industrialised faster and became more attractive from an economic and social point of view, so the influx of Russians to these regions increased. For example, in 1897, they made up 68% of the workers in the heavy industry of the then-Katerynoslav province, despite the fact that, according to the census of the same year, the general population of the province was 69.7% Ukrainian, and only 17.3% Russian.

From then until the 1950s, Russians migrated mainly to large Ukrainian cities and industrial centres. And they did so more actively than Ukrainians. The proportion of Russians among the urban population grew: from 25% in 1926 to 29% in 1959. In general, during the Soviet era, the number of Russians in Ukraine increased from almost 3 million in 1926 to more than 11 million in 1989. However, these figures are not entirely reliable, because the empire also actively used passportisation as a tool of assimilation.

Passportisation

In the times of the Soviet Union, from 1932 onwards, the policy of passportisation was widespread. Besides registering citizens, it had a much more pragmatic and unlawful function. As a result of passportisation, certain strata of the population, such as peasants, essentially became serfs. They did not receive passports, and therefore did not have the right to leave their village or change their professional activities. In fact, they did not have any of the rights supposedly enjoyed by Soviet citizens.

Passports had a significant impact on indicators of people’s national self-identification. Since in the cities they were mostly issued to Russians and marked “Russian” in the nationality column, population censuses clearly show that there were allegedly more Russians than other nationalities on the territory of Ukraine. Sometimes Ukrainians were registered as Russians against their will, or else certain unsafe conditions were created, under which it was beneficial to agree to being registered as such. People were left with no choice. Soviet authorities considered that people with official public positions, party jobs, or military ranks should be role models for others. And that meant being a Russian – or pretending to be one.

This can be easily illustrated with surnames. Many families have stories of how Ukrainian surnames were Russified by adding typical Russian suffixes such as -ov or -ev. There were also numerous other methods of bringing authentic Ukrainian surnames in line with the “correct” and “official” Russian tradition (a similar pattern can be observed with Georgian, Kazakh, Armenian, Belarusian, and Lithuanian surnames). Thus, by means of these documents, Ukrainians were “turned into” Russians. A Zhuravel would become a Zhuravliov, while a Shvets would become a Shevtsov.

Some people also sought to change their surnames themselves, to have a chance for a better life: for example, in the 1930s, during the policy of korenizatsiya (“nativisation”), Ukrainians had much less chance of holding government positions. A vivid description of these processes can be found in Ukrainian literature: the main character of Mykola Kulish’s play “Myna Mazailo” wanted to change his Ukrainian surname to the Russian “Mazyenin” in order to be promoted at work and generally more respected.

The same colonial modification applied to the names of cities. This is why we now insist on saying Kyiv instead of Kiev, Mykolaiv instead of Nikolaev, Kharkiv instead of Kharkov, Odesa instead of Odessa, and so on, because this marks these cities as Ukrainian, not Russian.

Korenizatsiya (“nativisation”)

A policy of the Soviet government in the 1920s and 1930s, aimed at strengthening the positions of the ruling party in the regions through demonstrative involvement of the local (indigenous) population in power.Russia has not abandoned its policy of passportisation, aware that it is a powerful and important tool of totalitarian government. For example, after the liberation of the Kyiv region from the Russian military occupation, Ukrainian law enforcement officers found USSR-era passports. The Russian Federation had planned to create an occupation administration in these territories and keep records of the local population through these handed-out passports. And, of course, to establish fictitious grounds for talking about “historically Russian territory” in the future.

Since 2014, the Russian Federation has been issuing passports of the so-called LPR and DPR in the temporarily occupied territories of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, which it uses as a means of pressure and manipulation. People have had no choice but to accept them, and the Russian authorities later took advantage of this. The terrorist state of the Russian Federation itself does not recognise the legal force of these “passports”, but forces people to obtain “citizenship”. The Russian Federation literally uses this “document” to destroy Ukrainians. For example, it is primarily men with “LPR” passports who are subject to mobilisation in the temporarily occupied territories of the Luhansk region.

The compulsion to change one’s surname is still an effective tool of imperialism in territories where Russia dominates economically. For example, in Kyrgyzstan, young people Russify their names and surnames in order to get a job in Russia or even simply to be able to enter the country.

Deportations of Ukrainians

In parallel with the Russians’ settler colonialism, permanent deportations of Ukrainians took place. The practice of forced resettlement became especially widespread under the Soviet regime. From the 1920s to the 1960s, there were about 10 waves of deportation. Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars suffered the most, but other peoples were also affected: Germans, Czechs, Poles, and Armenians.

The eastern territories of Ukraine suffered the most in the 1920s and 30s. Then the so-called “Kurkul expulsions” took place. Wealthier peasants were sent deep into Russia and their property was confiscated. In 1930–1931 alone, 63,817 peasant families from the Ukrainian SSR were deported to the Urals, Eastern and Western Siberia, the Far East, and Yakutia. Many of them were not wealthy at all and only had a single cow. Nevertheless, not even the absurd formal criteria mattered to the unpunished Russian authorities.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Ukrainians and people from other nations were sent to Kazakhstan as part of the Virgin Lands campaign. In the early post-war years, the USSR faced significant food shortages. Its State Plan of 1954 planned to plough at least 43 million hectares of virgin and fallow land in Kazakhstan, Siberia, the Volga region, the Urals, and other regions of the USSR. The campaign was carried out without any prior preparation, with a complete lack of infrastructure — with neither roads, granaries, qualified personnel, nor a repair base for equipment. The authorities failed to take into account the climate conditions of the steppes, with their sandstorms and droughts; they adopted a soil cultivation culture that was unsuitable for local conditions and used grain varieties that were not adapted to the climate. People were sent to dry fields and forced to build hospitals, warehouses, and homes from scratch. In particular, students and youths were separated from their home environments and thrown into adverse circumstances in foreign lands, where they underwent Russification. This contributed to the implementation of the policy that aimed to form “one Soviet nation”.

These days, Ukrainian victims of devastating Russian shelling and blockades are being deported to Russia. First, they have to go through terrible and humiliating filtration camps. Their smartphones and Ukrainian papers are confiscated under threat of violence, and they are issued with Russian passports and work permits, forcing them to remain in remote areas without the right or opportunity to escape. Deported Ukrainian children will be adopted by Russian parents. They will be raised in an atmosphere of hatred towards Ukraine and indoctrinated with the imperial Russian mindset. In October this year, Maria Lvova-Belova, the Russian Children’s Rights Commissioner, “adopted” a child who was abducted from destroyed Mariupol.

The main goal of all deportations is the assimilation of oppressed nations into the colonising nation and the complete destruction of their identity. Thus, at great length and in cold blood, the aggressor countries are destroying those who, in their opinion, should not exist. Russia vulgarly disregards Ukraine’s right to exist and its independent orientation in the world. Whenever Ukraine takes a step or declares an intention in the name of vital national interests, this is always interpreted as being directed against Russia. Or, in the context of the global conspiracy, the Ukrainian strategic “dare” to limit Russia’s imperial capabilities. As the present-day full-scale war unfolds, Russia continues to actively apply these practices, using propaganda narratives that were created centuries ago.

These myths, which have undergone evolution and reformulations over time, put Moscow’s distorted image of Ukraine’s past into a perspective that is useful for Russia. Russia’s ultimate goal is not limited to its ideological influence on Ukrainians and Russians. Throughout the world, Russia is shaping a manipulative and erroneous perception of the Ukrainian state and history, which is skewed in Russia’s favour. In the 19th and 20th centuries, these false narratives were supposed to justify the regularity of Ukraine’s status as a part of the Russian Empire and the USSR. Nowadays, these narratives are used to bolster the “naturalness” of the Kremlin’s claims that Ukraine belongs to the space of “legitimate” Russian influence, with the prospect of its absorption into the Russian Federation.

In fact, Russians have consistently pursued an anti-Ukrainian policy for several centuries in a row; today, with renewed cruelty, they continue their mission to exterminate the Ukrainian nation, constantly lying about what they are doing. Political repressions in occupied Crimea, war crimes in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, and full-scale warfare with genocidal massacres of civilians in places such as Mariupol, Izium, Borodianka, Bucha, and Kherson, are just a few tragic stories to illustrate this historical fact.

It should be noted that for almost two hundred years, Western intellectuals have been drawing information about Ukraine and its past mainly from Russian historical and journalistic works. Obviously, this information was presented in line with Russian concepts of history. Therefore. They have fallen under the powerful influence of Moscow’s myths. This is precisely the origin of most of today’s misunderstandings, and can also explain the inadequate response of the west to certain chapters of Ukrainian history, as well as the inconsistent interpretation of the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian war.

supported by

This material was created with the support of International Media Support (IMS).