Russia’s media propaganda is infamous around the world. For decades, the vast army of media specialists has been working on two fronts: abroad and at home. Through the media, Russia has complete control over the information space within the country, as well as the ability to promote its own narratives, manipulate facts and try to divert attention from important events and its own crimes abroad.

For years, European countries have systematically repelled Kremlin propaganda efforts, ranging from botnet attacks to staged media campaigns. The problem’s scope is indicated by the formation of the East StratCom Task Force. Created in 2015, the organization is aimed at countering Russia’s disinformation campaign. The cases of Kremlin media attacks are all carefully collected into a single database. Putin has succeeded in creating an alternate reality that exists on the fringes of common sense. With the beginning of a full-scale war, the Russian information space is more and more reminiscent of Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass. Only the protagonist of the story is replaced by the deluded dictator Putin, who informationally poisons Russians with their tacit consent.

slideshow

Was there ever freedom of speech in Russia?

Censorship in Russia зbegan virtually as soon as the Russian state was established. Initially, it manifested in control over the spiritual life—the Russian Orthodox Church monopolized its power, and church hierarchs supervised the books’ contents within the country. The first documented permission for church censorship may be found in 1551’s “Stoglav” (the Book of One Hundred Chapters), where, among other things, it was allowed to view manuscripts before selling them. In the 17th and 18th centuries, censorship repression grew more widespread. The “political undesirables” (especially those representing the cultural sphere) were eliminated, as were manuscripts and books.

Under the reign of Peter I, who gradually dismantled the church’s monopoly over cultural life, religious censorship was replaced by secular censorship. Undoubtedly, the Russian tsar was able to elevate culture to a new level, but now it was the tsar himself and his assistants who became the main censoring stronghold. In 1708, during the war with the Swedes, Peter I issued an order, which became the first document of military censorship.

Empress Elizabeth continued her predecessor’s practices, although they were more chaotic; Catherine II stimulated cultural life while clearly regulating it. Censorship gained official status and was institutionalized under Catherine II’s rule. It was implemented as a combination of secular and religious censorship. Catherine II honed propaganda processes by establishing the “Vsyakaya vsyachina” magazine, which was intended to shape public opinion in Tsarist Russia. It is a form of “convenient journalism” that consciously rejects topical issues and instead praises life in the country.

Although de jure censorship was abolished in Russia in 1905 (Tsarist Manifesto), it has persisted since then. For more than 100 years, only the tools and scale of the persecution of freedom of speech have changed. Today, the same things are illegal as they were in Tsarist Russia: any material that discredits the government and the church, incites “strife,” or is immoral in the eyes of the ruling elite.

Traditional Russian censorship is a harsh means of fostering a subservient society. Fines, suppression of newspapers and printing houses, bribery and repression: at the beginning of the 20th century, the government almost completely controlled the media. Under the cover of martial rule, the “Temporary Regulation on Military Censorship” was issued just before the start of the First World War in order to unleash the authorities in their campaign against unfavorable media.

With the formation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the communist authorities diligently developed the cult of a superpower that was “ahead of the whole planet.” The myth of the uniqueness of the USSR, its government, and its people was promoted in the news, literature, cinema, and public space (posters, leaflets, signboards). The reality of the shortage of goods and the constant surveillance and persecution of dissidents did not coincide with the socialist realism of that time.

SOCIALIST REALISM

A concept that characterized Soviet culture and art from the 1930s to the 1980s. The imposition of the state-approved style and method on artists is a hallmark of socialist realism.The cult of personality reached its pinnacle under the rule of Stalin. The narrative that the West is to blame for all the troubles and the United States is the abode of evil has become entrenched. As mentioned briefly in this article, Soviet propaganda was a phenomenon of incredible scope and influence. This is the subject of research in many interdisciplinary studies because the consequences of this impact, unfortunately, are still not completely eradicated.

Putin, who considers the dissolution of the Soviet Union the greatest geopolitical disaster of the 20th century, has succeeded in resurrecting almost all the tools of Soviet propaganda. He sticks with the tried-and-true scheme of fakes and bans. His approach to the media sphere follows the logic of “if you are not with us, then you are against us.” A number of legislative decisions have allowed Putin to destroy the independent press and to keep a tight rein on civil society year after year. As of 2021, Russia ranked 150th out of 180 countries in the World Press Freedom Index. For comparison, Ukraine was ranked 102nd in 2019, 96th in 2020, and 97th in 2021.

Suppress and Rule: Modern chronology

In 2012, during his second presidential term, Putin imposed stricter information control that included monitoring both print media and the Internet. The authorities received tools to censor and restrict access to information.

2012

Russia’s law “On Information, Information Technologies and Information Protection” allows blocking websites without a court decision. A “black list” appears that is managed by Roskomnadzor. As a result, more than 100,000 websites and more than 4 million web pages were blocked (as of July 2018). The number of banned sites included in the special register growsyear after year: in 2020, 4931 sites were banned, and in 2021 — 7018. Apart from Roskomnadzor, other agencies that initiate the blocking of websites include the Prosecutor General’s Office, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Federal Taxation Service, etc. As a result, almost 175,000 sites were on Russia’s register of banned websites.

ROSKOMNADZOR

The Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology, and Mass Media Communications

2013

To defend the traditional concept of the family, Putin prohibits so-called LGBT+ propaganda, particularly on the Internet, and fines both individuals and the media (Article 6.21 of the Code of Administrative Offences). The Criminal Code was amended so that “public actions that express clear disrespect for society and are committed in order to offend the religious feelings of believers” can lead to a fine or imprisonment for up to three years. According to those amendments to the Criminal Code, public calls for actions that endanger the Russian Federation’s territorial integrity can result in a 5-year prison sentence. The “Lugovoy Law,” named after a Russian Duma deputy, allows authorities to block Internet resources that, in their opinion, encourage extremist activities without a court order.

2014

As part of a major campaign against terrorism, the so-called “Bloggers Law” was adopted. Bloggers with an audience of more than 3,000 unique visitors had to register with Roskomnadzor. As there was no clear definition of the term “blogger” in the law, many users of social networks fell under that category. That is, they could be responsible for any post, repost, or comment. They were also obliged to indicate their real name, surname, and contact details. The law was in force until 2017.

Nostalgia for the USSR and glorification of the Second World War, known as the Great Patriotic War in Russia, manifested itself in a supplement to the Russian Federation’s Criminal Code. For the dissemination of “fake information” about the USSR (during the Second World War) and the so-called “rehabilitation of Nazism,” one can end up behind bars. Instead of conveying the conflict’s factual history, Russia is painting a rosy picture of the Second World War. This contributes to the establishment of narratives about Russian power and valor, as well as Russia’s unique role in maintaining world order. Any attempt to present an objective history of these events may be risky for Russian citizens.

New amendments to the Russian Federation Law “On Mass Media” have reduced the share of Russian media that can be owned by foreigners from 50% to 20%. They were labeled as “foreign agents.”

slideshow

2015

The confidentiality of Internet users’ personal data is under threat as a new law requires that their data be stored only on servers located in Russia.

2016

A law came into force that required news aggregators to verify and be responsible for publishing “socially significant” information. The authorities may question the article’s “veracity” and demand the aggregator remove it within 24 hours. The law also prohibits foreign ownership of news aggregators whose content is provided in Russian or in the languages of the country’s ethnic minorities.

The “Yarovaya law” obliged communication operators and Internet service providers to store information about users’ activities for at least 6 months, as well as provide it to security services upon request (even without a warrant).

Electoral legislation regulating media work has been amended to prevent Russians from exercising their right to access information during the election campaign. It’s allowed for those accredited journalists who meet certain criteria (2 years of work experience and official employment) and who have gone through incessant bureaucratic warnings from the election commission’s organizers about their intention to take photos or videos.

2017

The first restrictions on VPNs and Internet anonymizers have been imposed. Messenger users are being identified by their mobile phone numbers and are losing their right to anonymity.

VPN

While remaining anonymous and concealing your geolocation, a virtual private network creates secure Internet connections and helps to avoid online censorship. Both foreign and Russian media can now be labeled as "foreign agents."The set of conditions that grant such status is rather vague: it’s enough for the media outlet to have foreign funds or property (including refunds from Airbnb, Amazon, etc.), or engage in political activities (the interpretation of “political activity” is also not specific).

2020

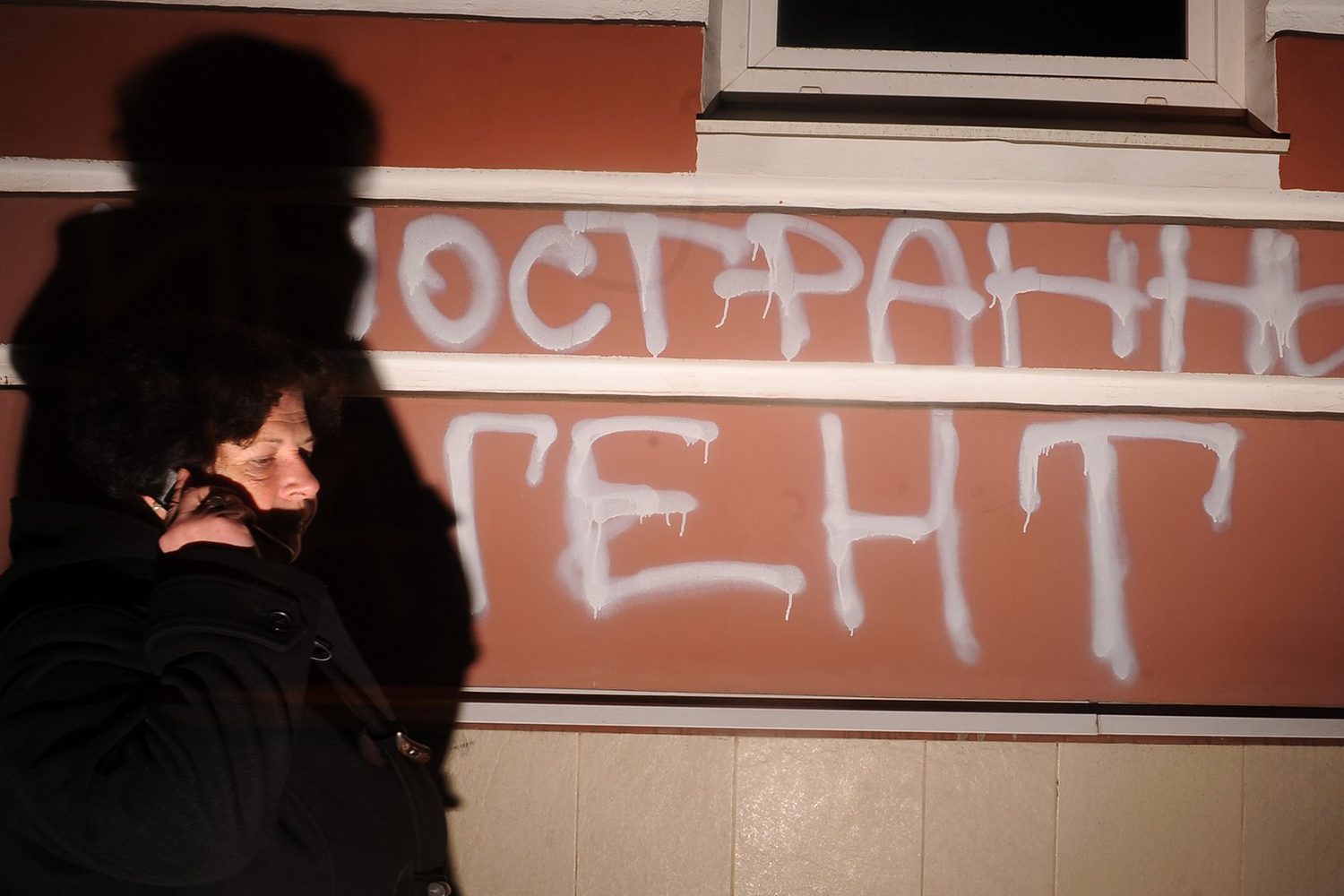

Not only NGOs and media outlets, but also individuals can be considered “foreign agents.” The first on the list were human rights activists, artists, and journalists who worked with Sever.Realii, a media project of Radio Liberty’s Russian service that covered events in the Russian Federation’s northwestern district according to journalistic standards.

In Russia, the status of “foreign agent” is almost synonymous with the word “spy,” which dates back to the days of the KGB (USSR’s Committee for State Security) and stigmatizes participants in the information field. “Foreign agents” are required to: appear on Roskomnadzor’s special register; mark with a specially defined text all their materials (that were published before and after obtaining this “foreign agents” status); undergo regular audits and report on their activities to the Ministry of Justice; and register a legal entity in Russia (this also applies to individuals). As a result, this has weakened media outlets’ positions and created additional obstacles for journalists, such as fewer people willing to give interviews and comments. The number of business partners and advertisers has also decreased.

Failure to comply with this law can result in fines or imprisonment for up to two years. No one has yet managed to appeal the decision that grants the status of “foreign agent.”

Illustration: @sergeygrechanyuk

Can it get any worse? It can

Putin rules not only from his bunker but also through the television screen. “Television is the only force that can unite and strengthen this country and govern it,” wrote Peter Pomerantsev, who is a specialist in modern Russian propaganda and media, and the author of “Nothing is True and Everything is Possible.” According to PEN International, the Russian government controls the information space through the state-owned media and through individual owners affiliated with the Kremlin. In the pre-war period (when everything went “according to plan”), opinion polls showed that in early 2021, television remained the main source of information about Russia and the world for 64% of Russians. Social networks are viewed as a source of information by 42% of Russians, with VKontakte leading the way among the other platforms. Objective media cannot exist when subjected to the above-mentioned list of draconian laws.

PEN

An international non-governmental organization that brings together writers, translators, and editors to defend free speech and safeguard humanity's cultural history.After monitoring the Russian infospace during the full-scale war, it seems that the media had no backup plan. While the Russian military brought parade uniforms and medals for the conquest of Ukrainian cities, the Kremlin’s propaganda machine was gradually creating draft versions of articles on the “triumphant denazification.” To avoid information chaos, Russian authorities are closing or blocking liberal media outlets that have dared to oppose the media agenda. They include Echo of Moscow, Novaya Gazeta, TV Rain, Meduza, Current Time TV, DOXA, Voice of America, BBC, Deutsche Welle, Crimea. Realities, and others. Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and various VPNs are also getting blocked. It may sound absurd, but Russian bloggers demanded that Meta pay 1 billion dollars in damage for the job loss.

slideshow

In March 2022, the Russian authorities adopted legislation that penalizes the distribution of “fake” information about the actions of Russian troops (3–15 years in a penal colony), calls for sanctions against Russia (up to 3 years in prison), and public actions that discredit the Russian army (up to 3 years in prison, fines). The word “war,” by the way, is also officially banned. Roskomnadzor ordered that any media that continued to use the word “war” remove the articles; several media outlets were simply shut down. The law, which became the last nail in the coffin of freedom of speech in Russia, was adopted unanimously and in three readings at once. The first criminal cases for “military fakes” have already been opened. Following the passage of the law, many media outlets announced their closure (Znak.com, Silver Rain Radio), restructured their activities (The Village relocated to Warsaw, Bloomberg and CNN withdrew their Russian journalists), or removed all of their materials from their websites. The Russian authorities force the media and ordinary Internet users to fall silent, regardless of the number of their subscribers. By reposting and commenting on “forbidden” materials, you can find yourself behind bars. The Russian authorities are so scared of the truth that they have prohibited the publication of an interview with Ukraine’s President conducted by Meduza (the media was branded as a “foreign agent”).

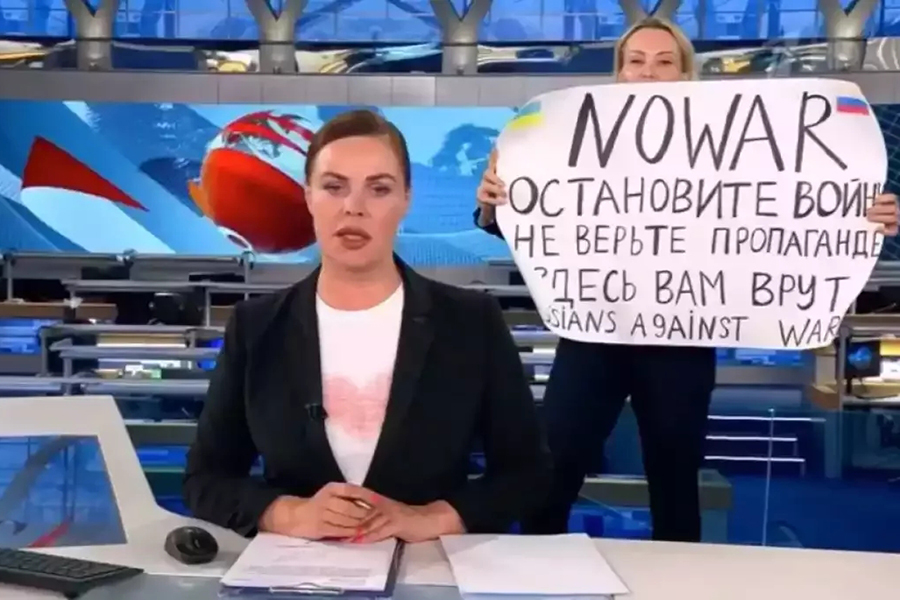

The illusion of the Russians’ innocence is reinforced by their propagandists. The journalist Valentyna Aksionova calls it the “game of the embarrassed liberal.” So far, the most striking example is Marina Ovsyannikova’s appearance on Channel One with the poster “No War. Stop the war. Don’t fall for the propaganda. They’re lying to you here.” The Western media swallowed this bait, perhaps not realizing that Marina Ovsyannikova is an experienced editor of Channel One, her social networks are full of attributes of the current war, and that her protest has the look of a low-budget production. The editors of Channel One quickly removed this fragment from their website, but it has already spread across the world’s media and social networks. As a result, Russia once again got her hands on the microphone and started singing the same old song: “no war, the Russians are not to blame, Russia and Ukraine are friends forever.” Ovsyannikova’s “social outing” changed the agenda: that morning, the entire world talked about the tragedy in Mariupol, and in the evening, they discussed the “heroism” of the media woman.

After violating the Russian law “On fakes,” Ovsyannikova got off scot-free after paying a measly fine of 30,000 rubles (about 366 dollars). By the way, the propagandist with fifteen years of experience changed jobs and now works for Die Welt. Ukrainians are outraged, while Germans seem to be fine with it. Ovsyannikova was to receive a Media Freedom Award in Eastern Europe from the German Weimer Media Group. Other laureates include Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Belarusian opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya. The award jury justified this decision by saying that “Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Russians are at the forefront of the fight against evil, war, and tyranny.” Put simply, the decision to award Ovsyannikova is supposed to deliver the message that, regardless of nationality, we are all friendly people who want peace. This is how propaganda triumphs over common sense.

slideshow

It is worth mentioning that Moscow State University’s journalism department has closed the educational module “Political Journalism.” The decision to merge it with “Social Journalism” was justified by the decreasing number of people interested in the speciality. Students who enrolled in this course went on to work in the Russian Federation’s relatively independent media.

Another nail in the coffin is Russian State Duma deputy Andrei Lugovoi’s proposal to create a separate law on “foreign agents.” The authorities decided to create a single register of “foreign agents” and related people on March 11, 2022. Censorship, of course, has the potential to escalate into isolated or mass repression. “They should be afraid,” said Andrei Lugovoi, whose words briefly illustrate the realities of life in the country.

TV screen instead of head

The media dictatorship provides a strong platform for spreading any of the Kremlin’s narratives. This is a method of shaping Russians’ worldviews in the most remote parts of the country, where television is the greatest good. For years, every television screen has broadcast images of great and mighty Russia, with its even greater culture. In fact, the country is so “great” that it is capable of anything, including the nationalization of IKEA. If there are any problems, it is, of course, the fault of the Western countries, who are always portrayed as petty and jealous.

In this parallel information reality, Russia is never guilty of any conflict because all of its participation is aimed at promoting peace. During the full-scale war against Ukraine, the propaganda machine modifies the narratives and spreads the idea that the Western media are escalating and exaggerating the situation. And, of course, all those outside the Russian Federation are enemies. This is how the Kremlin legitimizes both informational war and full-on warfare against everyone. According to recent polls, 71% of Russians support the war in Ukraine, though the objectivity of this data is debatable given Russia’s lack of freedom of speech.

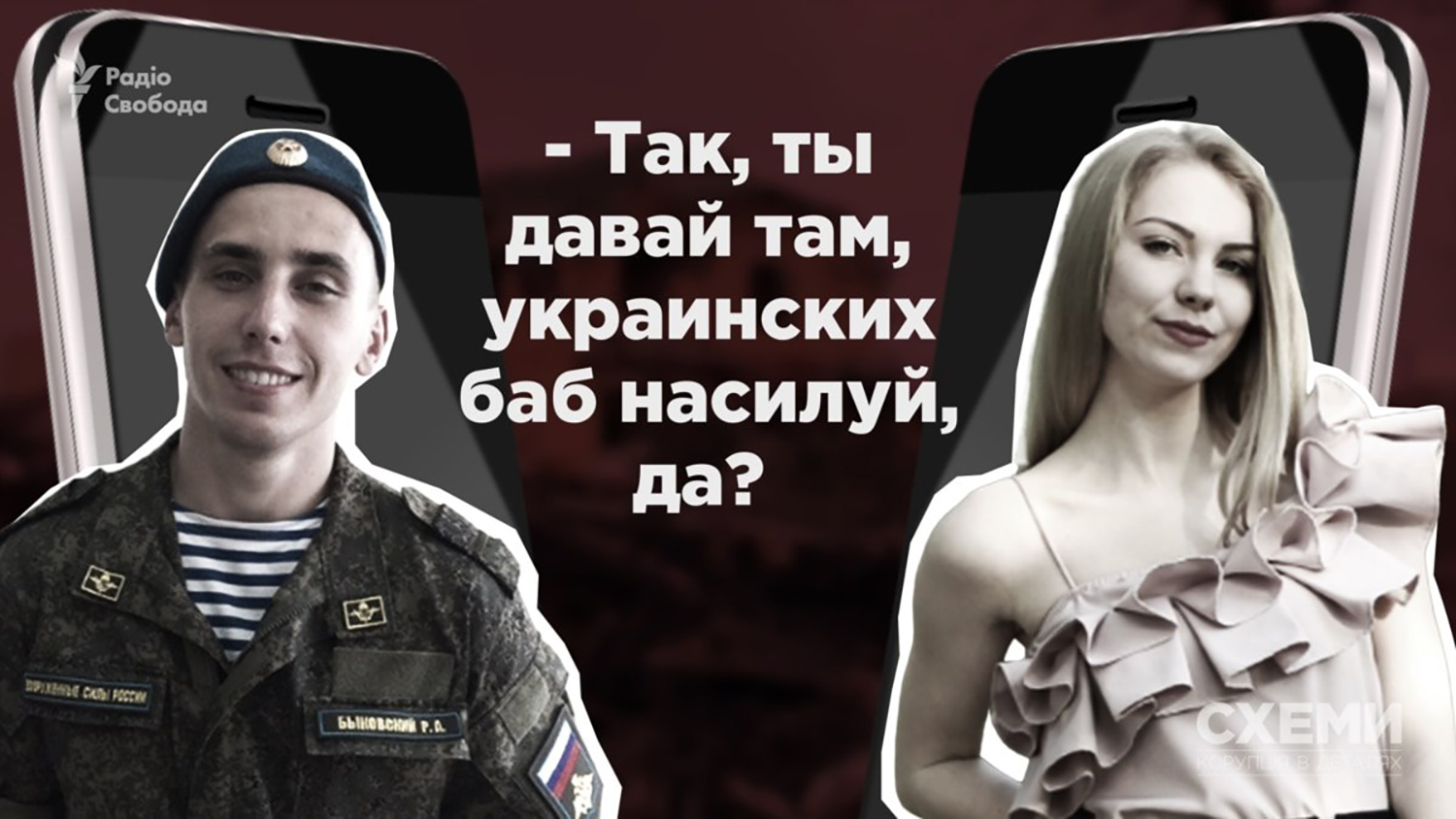

In all spheres, Russia is cultivating a hierarchical system of subordination. “I’m smart, you’re a moron,” is a common authority-society interaction model. Experts who study the Russian media environment note that the majority of their TV programs promote toxic human relationships and legitimize humiliation, aggression, and hatred. The same is observed in intercepted Russian soldiers’ conversations with their mothers and wives. The full-scale war has revealed one more thing: the Russians are so dulled by the propaganda from all the TV screens that they do not believe even what their close relatives say. The mechanism for critical information evaluation simply does not work anymore. This undermines the institution of the family in Russia and paralyzes civil society’s development. Those Russians who understand their society’s problems often decide to leave the country.

The cultivation of cruelty has backfired on Russian citizens, who are silently accepting a reality that they often find dissatisfying. Russians are more frightened of police vans than they are of a lack of freedom of speech. They do not think that they’re capable of changing anything. Of course, this is also an obvious result of the propaganda, which instilled the idea that all revolutions occur at the will of the government rather than that of the people. And so they wait for a political hero to appear and solve all the problems in the country. As a result, people become passive and support the cult of the dictator.