When the Holodomor (famine genocide in Ukraine) started, Mariia Hurbich was twelve. Not only did she survive the genocide of the Ukrainian nation together with her family, but she also helped a neighbour boy survive. They met by chance years later. And although what had been happening all over Ukraine in 1932–1933 resembles the time when some regions of the Donbas were captured in 2014 (the Russian occupation in the East of Ukraine — ed.) in that the poorest volunteered or were forced to become “activists” and had to take the last piece of bread from their neighbours, still people such as Mariia were secretly helping each other survive.

From 1929, the Soviet government was extensively creating collective farms (“kolhosps”). Having altogether eliminated the very concept of individual farming, they forced the villagers by “collectivisation” to join the kolhosps and thus deprived them of the possibility to earn their living. Then the regime took away all their food supplies having accused the Ukrainians of resisting collectivisation. But they resisted because working in a collective farm meant giving up the traditional ways of farming and submission to the new Soviet order. The Holodomor was a way to subdue the Ukrainians who resisted not only the new rules of farming but also the Soviet regime on the whole.

For many years after the Holodomor, the Soviet authorities had concealed the truth about it, prohibiting speaking about what the Ukrainian villagers lived through and how many people really died from hunger. The subject of the Holodomor was hardly ever officially raised in the Soviet Union or abroad.

In 1985, the US Congress set up the Commission on the Ukraine Famine. Its members wanted to investigate what had happened in 1932–1933 in the USSR to reveal the truth about the crime committed by the Soviet Union against the Ukrainian nation. In Ukraine, the archives were declassified, and the investigation of the Holodomor began only after the declaration of independence in 1991.

In 2003, Ukraine internationally declared the Holodomor as a genocide against the Ukrainian people. Then Russia, as the successor of the Soviet Union, addressed the international community with the appeal not to recognise the Holodomor as genocide, and later interfered in the process of approving the UN resolution on a number of occasions.

With this publication we are opening a series of stories, The Witnesses of the Holodomor, which were recorded on expeditions of the Ukraїner team and the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide as part of the project Holodomor: Mosaics of History with the support of the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation.

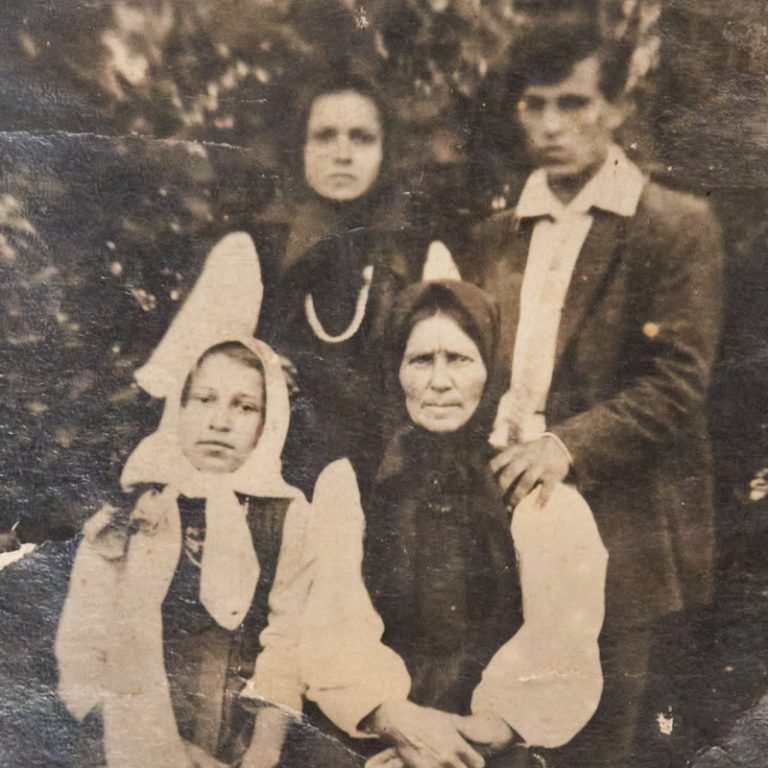

Mariia’s family

Mariia Hurbich (maiden name — Shovkun) was born in the hamlet of Vyla in the Losynivka district of Sivershchyna. Later she and her family moved to Oleksandrivka in the Bobrovytsia district, where they lived during the famine. Before the collectivisation began, her family was well-off; they had around ten hectares of land and a lot of cattle: four horses to plough the field, three foals, and three cows. This was enough to feed the large family of eleven people.

Two brothers of hers, one a university student and one a school teacher, were arrested on a case fabricated by the GPU (the State Political Administration) of the Ukrainian SSR, an organisation later succeeded by the NKVD. Both institutions served as the Soviet secret police agencies. The case was associated with the show trial of the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine (a fictitious political organisation invented by the GPU — ed.) and claimed that Mariia’s brothers, together with their fellows, strived to free the Ukrainian people from the Soviet regime and to establish an independent Ukrainian Republic through organising uprisings and rebellions. This case was an attempt to substantiate the mass persecutions and arrests of Ukrainians who opposed the new government and also to undermine trust in everything associated with Ukraine, in preparation for the Holodomor in particular.

NKVD

One of the main tasks of the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs of the USSR (NKVD) was fighting against the national movements opposing the authorities. The NKVD used inhumane methods to suppress any resistance against the regime.

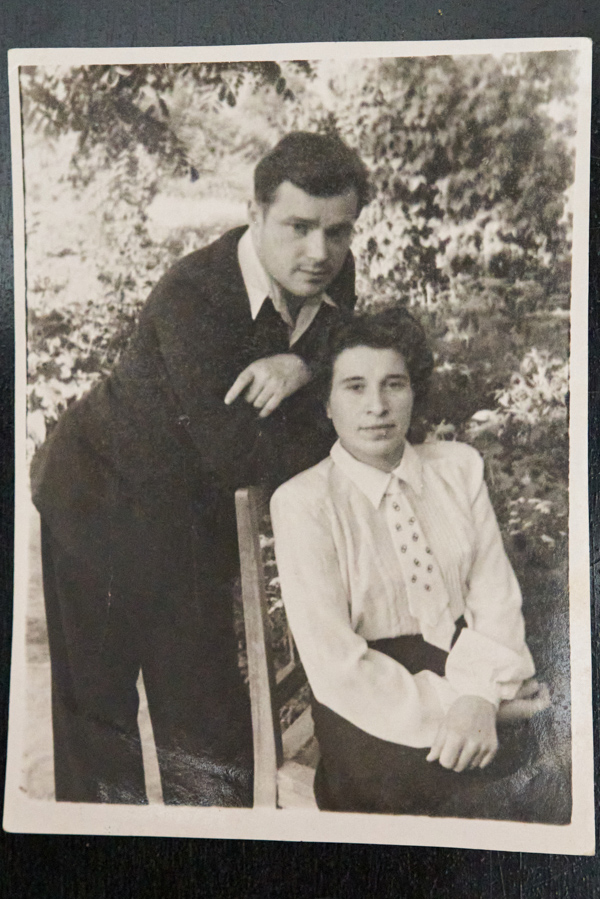

Mariia Hurbich with her husband Mykola.

During the whole trial of the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine and afterwards, over 30 thousand people were killed or forced into exile, predominantly the intelligentsia: artists and scientists. The Solovki Monastery was the place of detention for some of the convicts. That was where Mariia’s brothers were imprisoned for nationalism.

Their father visited them just at the time when he had to make a decision whether to join the kolhosp or continue running their own farm.

— And my brothers convinced him, “Father, join the kolhosp or you’ll rot in Kolyma.” So we joined the kolhosp, and we survived and weren’t dekulakised. (“Dekulakisation” was a part of the collectivisation campaign of the Soviet government; “kulaks”, the well-off villagers, were arrested or deported and their land and property confiscated. — tr.)

Kolyma

A colloquial name for penitentiary work camps in the northeast region of the USSR, the harshest in the Soviet system of labour camps, the Gulag.Mariia remembers that those who refused to join kolhosps even under the pressure of threats and intimidation — “the individual farmers” — were dekulakised and had no resources to live through the hunger. Or excessive taxes were imposed on them, which they just could not pay. Mariia’s family gave up all their implements for fieldwork and household work for the kolhosp, as well as their horses and cows. They received no compensation as the kolhosp did not pay them.

— Where would people in a kolhosp take money from if they were given 200 grams of bread for a working day? That’s how the state did it: we worked in a kolhosp for nothing, for nothing at all; people lived only off their vegetable plots. Nobody cared how they lived and survived.

The workers in kolhosp were supposed to get two kopeks, which added up to 150 karbovantsi (the official name of Soviet rubles in the territory of the Ukrainian SSR — ed.) in a year. This money was “borrowed” by the government to finance industry, the army, and medicine. People basically worked for food, which was handed out to them at the kolhosp, and often had no money even for clothes.

The mood in the villages

No more than 3% of the Ukrainians volunteered to join the kolhosps; others were forced to. They virtually had no choice as those who refused to join a kolhosp were doomed to die from hunger. Mariia’s father became a kolhosp worker, and later this decision saved the lives of his family because, in the time of the Holodomor, the kolhosp workers were sometimes fed so that they did not faint in a field.

At the age of twelve, Mariia already worked on over an acre of the kolhosp land herself, harvested crops, and turned them over to the authorities. It was a huge amount of work that even adult women did not always complete, for which they were fined. Mariia says that even before the Holodomor it was “indeed a satanic struggle for survival”.

Mariia remembers that 1932 was the year of floodings and loss of crops in Sivershchyna. People survived thanks to fishing.

— From Chernihiv to the very Chemer, everything was covered in water. From Nosivka to the very Bobrovytsia, everything was covered in water. The houses were under water, the village was under water, the streets were under water. But there were hills where there was no water.

Still, the loss of crops was not bad enough to lead to hunger. The yield of 1932 turned out to be only 12% lower than the average of the previous five years considering that the planting area was reduced by 20%. Kolhosps did not have enough human resources or seeds to complete the excessive grain procurement plans, and the forceful collectivisation was opposed by the people.

Grain procurement plan

A form of product duty from the villagers to the state according to which they had to supply the state with a specified amount of grain. It was one of the ways to control the villagers, their work and lives.This led to uprisings and protests in the Ukrainian villages. The Soviet government considered them acts of disobedience, which were the official cause for adopting a resolution calling for an increased procurement plan on 6 July 1932 as well as for deportations and legal repressions against the Ukrainian villagers. The new demands from Moscow intentionally exceeded the possibilities of kolhosps. That is why they took the food supplies from villagers (and often this food would rot in the warehouses) — so they wanted to exterminate the Ukrainians.

Neighbours

Mariia remembers how her neighbours would hide grain in their vegetable plots, and later other neighbours, appointed by the kolhosp, would come to conduct a search and take away everything they could find. All bags with food were confiscated, piled onto carts, and marked with a red flag (red representing Communism and the Soviet flag — ed.). Mariia says that such trains of carts were called a “red caravan”, but there was also another name for this process — a “red broom” (because it “swept” all grain from villages).

slideshow

Anybody could be appointed to search the houses of their neighbours, but not everyone did their work diligently so as not to take away the last food from their fellows. Mariia remembers vividly how people would hide beans behind their stoves, and the patrolmen would find them during their raids.

— I was told how once, in the house of a teacher Kalyna Hryhorivna Voloshchenko, Nazarenko (one of the patrolmen — ed.) took her bean soup out of the stove and poured it out to the waste. How can I describe it? They were preparing people for the famine, that is why they did things like this.

On 7 August 1932, the decree “On protection of property of state enterprises, collective farms and cooperatives and the strengthening of public (socialist) property” was adopted. Those who stole from the state were subject to confiscation of property and/or execution. This decree was better known among the people as the law “On five ears of grain” because even a few cut ears of wheat were considered a theft.

Mariia remembers that the patrolmen enforced this decree as well. After the crops were harvested, some uncut wheat ears remained in the field, or some cut ones were lying on the ground. It was forbidden to pick them up. One woman was imprisoned for five years for cutting around a kilogram of wheat. It was even prohibited to pick grains from the ground.

— What do you have that bag for? A patrolman can hit you, beat you up, take away the bag, and bring it to the office. That happened to me too. But we picked up wheat anyway. It would happen, for example, that we noticed we stayed in the field too long, and the patrolmen were on horseback, so we ran straightaway, and those who managed to reach home, brought some wheat.

A patrol brigade, 1933. Unknown author. Photo from the archive of Mykola Borysovych Oksiuta.

A portion of boiled peas

The hunger in the village became severe in January-February 1932. There were no potatoes, there was no flour. Those who had a cow had a greater chance of survival.

Mariia’s family also had two sheep, so they boiled some mutton stock with wild spinach or sorrel. In the kolhosp, a similar soup was prepared too, it was also called “balanda”. Besides the liquid, there were some peas in the dish so that the workers had strength to work.

Mariia said that she and her sister-in-law were given a considerable portion of boiled peas. One day she was walking across the field carrying a small bucket with their lunch from the kolhosp.

— I was carrying it and saw a boy running after me. He was around seventeen. He called me and said, “Let me scoop some peas from your bucket”, and he was holding a very big spoon. I was scared. I said, “Take! Take as much as you want.” He scooped a spoonful, devoured it, scooped another one, and said, “Go, I don’t need any more, take it home.” So, I brought it home, my mum was putting it into plates, and then my father said: “They gave water to the child.” I said nothing. Later I secretly told my mum that Mykola Nabok met me and asked for some peas. “It’s all right, daughter, let it be. We have a cow, we will survive.” That boy survived too. We met again when I was a student and he was a lieutenant. And we cried so bitterly as we remembered that moment. (Crying.) We were looking at each other, and I said, “Are you Mykola Nabok?” — “Are you Masha?” I said, “Yes, I’m Masha,” and we both started crying. And then we talked a bit, asked some questions. I’m happy that he survived, and all his family too: four children and their widowed mother. It was hard, but they did survive.

slideshow

Mariia’s family had millstones at home. They were kept secretly, hidden in the cellar. It was forbidden to grind grain with them or even keep them in the house (even though the authorities did not take away mortars). Mariia wonders why they would take away or break millstones.

— They did it to take away all the bread. To kill Ukraine. Whenever I recollect those events, whenever I ask myself why, the answer is always the same — to kill Ukraine.

The people from the neighbouring houses came together in the cellar and ground grain while they had some. When the supplies ran out, they switched to beans. They fried the beans, then soaked them in water, peeled, ground, and then boiled or fried some dishes from this. Mariia says those were “true delicacies” at that time.

— We ate wild spinach and weeds. If somebody had a press cake, we ate it too, and it was considered a real treat. If somebody had a press cake from poppy seeds or hemp, it was a treasure. We went into the field, and there was sorrel growing. Itty-bitty. Then there was burclover: we would pick it, dry it, and then grind and boil it. That was it. Just to fill the stomach in order not to die.

Mariia’s neighbour, Varvara Babko, had four children and lost them all in the first winter of the Holodomor. Mariia’s mother would sometimes bring them milk, but she could not do that often because she had to feed her own family. Neither the neighbours nor the relatives could help Varvara’s family.

One day after the first crops already after the Holodomor, Mariia came to Varvara when she was threshing a sheaf of wheat and saying, “Oh, the paths where your little feet trod have overgrown with weeds already”. The woman really suffered because of the loss of her children, and it broke her. Her neighbours empathised with her pain.

Mariia says that later Varvara married again the head of the kolhosp, and they had three sons. After she died, many years after the Holodomor, her grandchildren and fellow villagers installed a monument for her.

The villagers often supported each other. Everybody was suffering hardship — the Holodomor affected each family. Only joint actions and mutual support helped the Ukrainians survive while the Soviet totalitarian regime wanted to eliminate us.

There were many stories when it was impossible to save a life. And each of them is touching and painful even now, after so many years. Mariia recalls:

— A man was walking along the road and begging for food. He was dying. And I was grazing a cow. I ran to my mother shouting, “Mum, Mister Opanasii is dying”. My mum quickly gave some milk for him, and I carried that milk with my trembling hands. But he was already dead.

Fearing the truth

It was impossible to leave a village as villagers had no ID. They had to stay where death from hunger was waiting for them or risk their lives to escape from a village searching for food. Some managed to do it. Others sold their jewellery and family relics to “Torgzins” for nothing just to get some bread.

Torgzin

Abbreviation for “trade with foreigners”, special state-owned shops where goods were sold for foreign currency or exchanged for precious metals. In the years of the Holodomor, Torgzins sold food to villagers for exorbitant prices.

Mariia says that so many people died from the Holodomor in her village that the dead were lying right in the streets. A special cart was sent to pick up the bodies to bury them. The burial place was in the middle of the village, a mass grave.

Death certificates did not indicate hunger as the real death cause. According to the records, people were dying of pneumonia or other diseases. Officially, there was no hunger. Although those who had survived knew the truth (that the Holodomor was a genocide perpetrated against the Ukrainian people — ed.), they couldn’t talk about it for a long time, and they were afraid to.

— Apparently, that was the truth if now, in the modern world, we look at our country with the eyes Russia does. And if we remember those forced-labour camps where Ukrainians were killed. And not only Ukrainians, Germans as well (there was a colony on the Volga river), Jews, Tatars. Thus we can realise that Ukraine was being tormented like many other nations.

Mariia speaks about how people were doing everything possible to survive and help others. She often repeats that the Soviet authorities wanted to destroy Ukraine. But they never managed to.

The active and passive resistance of the villagers never stopped, neither before, nor during or after the Holodomor. People would hide food underground, refuse to work in kolhosps, or even attempt to leave them, spread leaflets calling for protests, and sometimes even burn down buildings or property belonging to a kolhosp. The protest waves were local, but they gradually involved more and more villages. This did not prevent the genocide planned by the Soviet government, but it demonstrated the resolute defiance with its actions and readiness to stand up for what belonged to you.

supported by

The material was published in cooperation with the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide with the support of the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation.