When the Holodomor (famine genocide in Ukraine) occured, Tetiana Krotova’s family lived in the hamlet of Shevchenko, situated near Kropyvnytsky city. The head of the local collective farm (“kolhosp”) became a criminal to the Soviet government and secretly gave food to the villagers — the same food that was taken from them and left to rot before. There were no traitors in the village who cooperated with the authorities, so no one died during the Holodomor.

Being only four years old, Tetiana Krotova learned all the horrors of the Holodomor. She saw “dekulakisation” (the process of eviction and confiscation of all property — ed.) of the villagers with her own eyes and had to eat uncrushed grains of wheat, fearing that someone would expose her. Her parents moved from place to place, going to work in each of the local kolhosps to somehow feed their five children. Being an adult, Tetiana continued learning the terrible truth about the events of her childhood that became a part of the history of Ukraine — the Holodomor of 1932-1933 — from her neighbours’ stories.

The Holodomor in Podniprovia. The hamlet of Shevchenko

Tetiana Krotova (maiden name Zaitseva) was born on 30 October 1928 in the hamlet of Shevchenko (today known as the village Travneve) which is situated near Kropyvnytskyi (formerly Zinovievsk, then Kirovohrad) in Podniprovia. She was the fifth child in Ivan and Ahrafyna Zaitsev’s family. The family got the land in the hamlet in 1924 from the Soviet government and the same year moved there from the village Rivne and started building their own house. Both parents worked in a kolhosp.

Tetiana recalls that the harvest of 1932 was not much less than the previous one. The grain was harvested from fields and brought to an empty house by order of the kolhosp leaders. It was neither sent to a city nor exported. It just kept lying there and rotting.

According to Tetiana’s recollections, no one died of starvation in their hamlet. Partially thanks to the head of the local kolhosp, Nykyfor Romanenko.

— Every night he gave a list to a storekeeper: it was written how much wheat (from what had been confiscated) he should give to a family, depending on its size. And the next day, another family was given it. If it had reached the authorities, he would be shot, of course.

People feared to pound the grain in a mortar (because someone might hear it), even though they knew there were no traitors in the village to denounce it. However, being afraid of a sudden inspection or even an alien passing by a house and hearing that the grain was pounded, the villagers did not take a risk to do it.

The locals sometimes went to the nearby villages to seek some food. They walked 10 or even 20 kilometres to exchange household items for something edible.

Thanks to the loyalty of the kolhosp leaders, the Zaitsev family managed to save their cow, so they had milk at home. Wheat was cooked whole in a pot.

— Right now, it seems like in front of me is a bucket-sized pot that my mom pulls out of the stove. And the boiled wheat is so swollen. It was not the same as it is now: a separate plate for each one — we had big clay bowls. My mom pours the wheat into a bowl, adds some milk — and that is the food for our company.

Whole grains take a long time to digest. So that no one noticed the remnants of wheat in human waste, they used a barn as a toilet. Undigested grains were later picked by chickens there, so they continued to lay eggs.

Moving to Hromukha village

In 1935, the Zaitsev family moved to the father’s relatives in Hromukha, which is situated near the village of Rivne. The family settled in a house, the previous owners of which were evicted as they were classified to be “kulaks” (more or less wealthy villagers who underwent the process of dekulakisation — ed.).

The staff of Tarutyno school. Tetiana Krotova is in the top row, third from the left.

Neighbours told Tetiana that the hunger in Hromukha was more severe than in the hamlet. People ate mostly burdock roots, they went to the local cattle burial ground to find meat, and they ate remnants of dead horses. Previously harvested grain was not transferred anywhere. Same as in Tetiana’s native hamlet, it was poured in a pile in one of the kulak’s houses. This house was also used for other household’s needs: cows and chickens were held there, and their waste was mixed with the grain, making it a pile of manure.

Meanwhile, the residents of Hromukha were dying en masse because they had nothing to eat. This is how Tetiana’s aunt Melaniia Shynkevych lost her daughter. It was the only death in their family. However, whole families often died. In particular, the parents of the Zaitsevs’ neighbour Mariika Chabanka died. The whole family of an acquaintance of the family, Foma Tsybulia, also died. In search of work, he went to Zaporizhzhia, and when he returned home, he got to know that his wife and three children had died of starvation. The parents of a neighbour across the street, Larion Lenetskyi, died of starvation. Two boys, Ivan and Sashko Kinsh, had lost their mother and father, and Tetiana’s parents helped them in every possible way.

By order of the local kolhosp head, the dead in Hromukha were taken away and dumped in the local cemetery. Sometimes people who were still alive were taken there.

— The head of the kolhosp sent more than half of the village to eternity. A squad of two strong men with a cart and oxen used to go around the village every day, visiting every house. People said that not only the dead, but also the alive (though they were almost dead) were taken to the cemetery. There was no pit — the bodies had been dumped in a pile, until in 1935 they dug a pit and rolled the bones into that grave with rakes.

After the head of the kolhosp died, the villagers did not want to bury him properly.

— When he died, the pit was dug by tractor drivers. The coffin was made in the kolhosp, and he was not even brought to the cemetery by car, but by a tractor with a trailer. The drivers did not want to take him through the village, but drove him about five kilometres through the forest. They made a large circle and, entering the cemetery, lifted the trailer — the coffin flew out of it. No one cared how it fell there, either sideways, or straight — they just covered it with soil. That’s how the villagers buried him for all the “good” he had done to people.

In Hromukha, raids in search of food took place even in 1935. Local activists continued to take away any food from the villagers, conducting house inspections, which, according to Tetiana, never happened in the Shevchenko hamlet. Although their family was not touched (as newcomers), she remembers well the story she heard from her neighbour Mykola Hromko. Their yards were nearby, across the river.

— He was born in 1928, just like me. He said there were five children, a grandmother, a father, and a mother in the family. The grandmother and mother were good craftswomen: they wove cloth, sackcloth. And it was in the Holodomor that the father either took a piece of sackcloth, or a tablecloth, or took a piece of cloth and went to the other villages to exchange. Once he exchanged it for a sugar beet. They already washed it but they didn’t peel it, so as to not throw away the excess. They washed it and put it in the stove. There came the activists, well, without the kolhosp head, to check whether there was some food, or they took everything to the gram. And they smelled the beet from the stove. He (neighbour Mykola — ed.) told, “They opened the damper, took out that bowl, put it on the table (four or five of them came in), made a circle, ate it,” he said, “to a piece. We, the children, were not left even a piece.”

Children who became orphans during or after the Holodomor were cared for by the kolhosp patronage (like an orphanage — ed.). It operated in Hromukha, where children from all the surrounding villages were taken. Once there, they had at least some chance of survival.

— It was like this — an old woman lived alone. She cared for these children, cooked for them, and received rations for them. It was issued every day from the kolhosp barn. And so these children were there until adulthood. Then the boys joined the army, and the girls got married. Everyone stayed in this area — in our village, in neighbouring villages, or in the district centre. No one returned to their homeland, because there, apparently, none of their relatives remained, and no one was looking for them.

Immigrants from Russia tried to settle in the empty houses left behind by the dead. Thus, four to five families from the Murom district of the Vladimir region of Russia appeared in Hromukha. The new residents brought a lot of food from home: potatoes, peas, pears. However, none of them settled in a new place. Only one Russian woman married a local man and stayed in the village until her death.

Immigrants from Russia

According to the secret resolution, “On the resettlement of 21,000 families of collective farmers to Ukraine”, in late 1933 to early 1934, hundreds of echelons of migrants were sent from Russia and Belarus to Slobozhanshchyna and Prychornomoria in Ukraine. In Ukrainian villages, they were provided with housing and significant benefits.

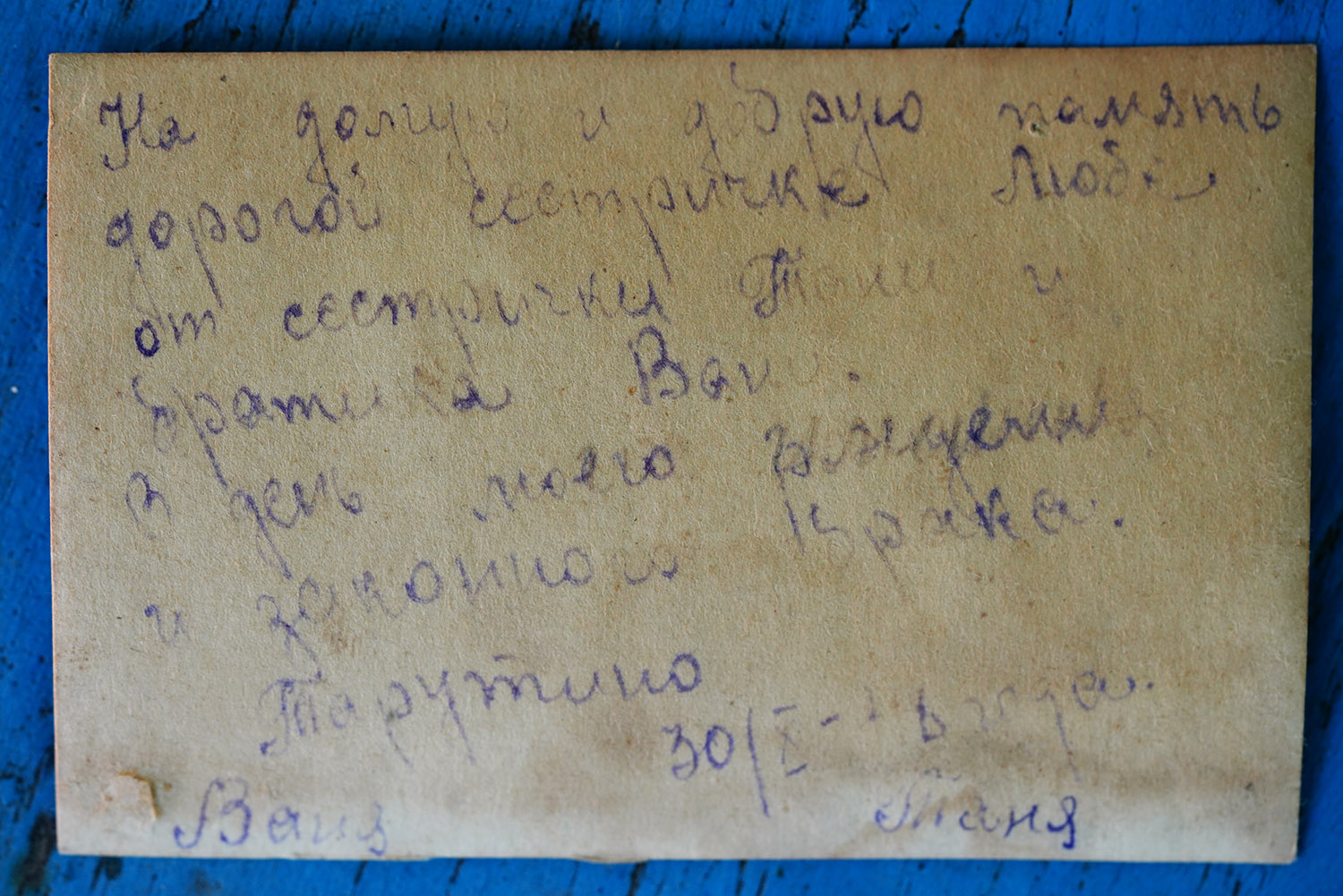

Wedding photo of Tetiana and Ivan. Tarutyno village, October 30, 1948.

Memories of Tetiana’s husband

In 1945, when some territories of Ukraine were still taking part fighting in World War II, Tetiana Krotova became a student of a high school in Kropyvnytskyi (then called Kirovohrad). At the time, in Hromukha, people starved, too, although there were no cases of death of starvation in the postwar period. The girl received a scholarship of 33 rubles and, most importantly, 500 grams of bread every day that let her survive.

In 1948, Tetiana graduated from the high school and according to the planned distribution began working as an educator in an orphanage in the village of Tarutyno, in Bessarabia. There were two such houses in the Tarutyno district — after the Holodomor of 1932-1933 and the mass artificial famine of 1946-1947, many children became orphans.

Inscription on the back of the wedding photo of Tetiana and Ivan.

She got married there, and in 1950 she became a teacher in the local secondary school. That same year, the couple had a son.

Tetiana’s husband, Ivan Krotov, remembered the years of starvation well and shared his childhood memories with his wife. He was born in Hrodovske village of the Mostove district in Prychornomoria. He was from the descendants of immigrant serfs from the Orel province, who inhabited these lands during the Russian Empire. Ivan’s father died of starvation in 1932, and a year later his mother died. In addition to nine-year-old Ivan, his 11-year-old brother and five-year-old sister remained orphans.

— In their kolhosp, children were given rations: some grout, water, and one or two handfuls of flour. His older brother used to come take it when his mother was still alive. The mother herself did not eat and died on a couch. The three of them slept on the stove and walked past their dead mother for a few more days, thinking she was asleep. Horse meat was also eaten, although their weak stomachs did not digest it. He remembered that someone could go and defecate with a piece of horse meat, and another went and picked it up. They rinsed it in the river and ate it. There was a cemetery outside the village, surrounded by a wall of shell rock (the village was by the sea). They approached the wall on a cart, threw the dead over it, and drove on. That is how it was in my husband’s homeland.

Later, all three children were taken to a foster care in Odesa. After the seventh grade, Ivan entered a craft school, but World War II soon began. During the evacuation, he and his brother were sent to Ural (a geographical region of Russia, located around the Ural Mountains — ed.) and later to Kazakhstan. At the age of 18 he went to war, and after the end of hostilities he returned to Ukraine. That was when he met Tetiana in Bessarabia. There they united their destinies, starting a new life together.

supported by

The material was published in cooperation with the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide with the support of the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation.