Historically, Slovaks settled in Ukraine in two stages. At the end of the 18th century, the first of them – the Liptaks – came to Velykyi Bereznyi, a village that was then part of Austria-Hungary and now located in Zakarpattia. The Slovak community of Zakarpattia originates from here. The other Slovak settlers, responding to a Soviet campaign, moved from Czechoslovakia to Volyn after World War II, in search of a better life. Today, according to various sources, there are from six to seventeen thousand Slovaks in Ukraine, and the majority of them live in Zakarpattia. Here they have a Slovak school, a Slovak language television and a radio broadcast, dance Slovak folk dances and follow Slovak traditions.

On Saturday night, the village of Storozhnytsia rests. Here and there around the neighbourhood, the voices of children can be heard. In the old part of the village, preparations for the Sunday service are being done at the Roman Catholic church.

Slovaks populated this land at the beginning of the 19th century by invitation of the Uzhhorod prefect. But back then they moved to Jovra, a former guard settlement near Uzhhorod Castle. Later another settlement, Derma, was founded nearby, and in 1894 Jovra and Derma were united into one settlement. During the Soviet period it was renamed Storozhnytsia.

The Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary Church in Storozhnytsia is one of the very few Roman Catholic churches in Zakarpattia where the services are given in Slovak. Similar churches are in Huta and Turia Remeta villages.

Daryna Habor, a local resident, recalls how the church and its surrounding area played for her the same role as the house of culture does for today’s children in Storozhnytsia:

– I spent my childhood here. Kids of all ages gathered here. Many of them met their boyfriends and girlfriends who they later married.

For forty years (1949–1989), the church in Storozhnytsia held no services. Soviet authorities seized the church building from the village community and used it as a food storage. Daryna Habor’s grandfather, Ivan Zyzych, campaigned for the church to be restored since it had been very special to the local Slovak community. He sent letters to the authorities requesting permission to renovate the church’s derelict building, Daryna recalls:

– My grandfather and clergymen were the first to revive all this, and later the youth joined them. My mother [Myroslava], Milan Tovt, who now works at the TV studio, his sister and friends formed a group of about ten to twenty people. They all came here to pray near the ruins. There was nothing else here but ruins.

Thanks to their joint efforts and to the donations from neighbouring Slovak villages, the Roman Catholic Church was reopened in Storozhnytsia on Christmas Eve in 1989. Daryna remembers well a story about the Mary and Joseph figurines which her grandfather had brought from abroad for the church’s reopening:

– The church has two figurines – of Virgin Mary and Saint Joseph. Since church was banned in the Soviet Union, bringing them across the border was illegal. So, as my grandpa told me, they put these figurines in the back of their vehicle and covered them with a sheet. At first, the border guard even thought that they were dead bodies…

After the service, parishioners would usually go home for lunch. And after that, Daryna’s grandfather, who then lived close to the church, would bring out a small organ:

– The instrument was so loud it could be heard all over the street. Old people his age – men and women – would come out and sit on the benches saying, “Go on, Jánoš, play for us!” They would make requests for certain songs, “Play me this, play me that”.

Ivan’s musical talent was inherited by his daughter and granddaughter; they both played the organ during church services.

Хист до музики перейшов Івановій доньці і онучці: обидві грали на органі під час служб у храмі.

In addition to family traditions, Slovaks of Zakarpattia also follow their folk customs and celebrate Slovak traditional holidays.

Christmas is celebrated here on 25 December, and people follow the tradition of lighting a candle on their Advent wreath every Sunday for the four weeks leading up to Christmas. After Christmas, the carnival ‘Fašiangový ples’ begins – a tradition Slovaks share with Hungarians. This is a period of massive celebration before Lent. Everyone sings and dances, and people fry fánky – traditional sweet pastry.

Storozhnytsia residents strive to keep these traditions alive in their town. Everyone – locals, representatives of the Slovak consulate, members of the Slovak community, TV reporters – are invited to the house of culture:

– Slovaks have a tradition: at the end of the carnival celebration they ‘bury’ a double bass. It’s just a joke, but traditionally a man dressed like a priest walks in front of a coffin with a double bass inside, and old women, clad in black, perform the role of weepers at the back of the procession. It’s meant to show how they figuratively ‘bury’ all the music until the 40 days of Lent are over.

On Easter Monday, Slovaks follow another tradition called ‘šibačka’: young men lightly whip girls with ‘korbáč’, a traditional whip made out of willow branches. In the olden days, it was believed that this practice improved girls’ beauty and health.

May is known as the month of love among Slovaks and is when the wedding season begins:

– Before dawn on the first of May, a young man would put a decorated wooden birch pole next to the house where the girl he wants to marry lives. This is a tradition for both Hungarians and Slovaks.

In Storozhnytsia not that many families still follow this tradition. “I guess I haven’t seen more than a dozen houses with these wooden poles” – Daryna recalls. But in the centre of the village, they put up a tall pole decorated with ribbons every year in early May.

Naša Fajta

If one would ask the Slovaks of Storozhnytsia how they ended up in Zakarpattia, they would answer the same Myroslava Ohrazanska does:

– We were born here in Storozhnytsia. That’s how we ended up here.

Myroslava loved dancing ever since she was a child. She had to part ways with her passion after graduating from university until she was offered a job at Storozhnytsia’s house of culture. At first Myroslava ran a free dance club for kids but later she became an art director for the amateur dance troupe Naša Fajta:

– Then everything just happened. The children really loved dancing and began attending sessions regularly; they practiced hard and improved their skills until they reached a level that I honestly had never expected.

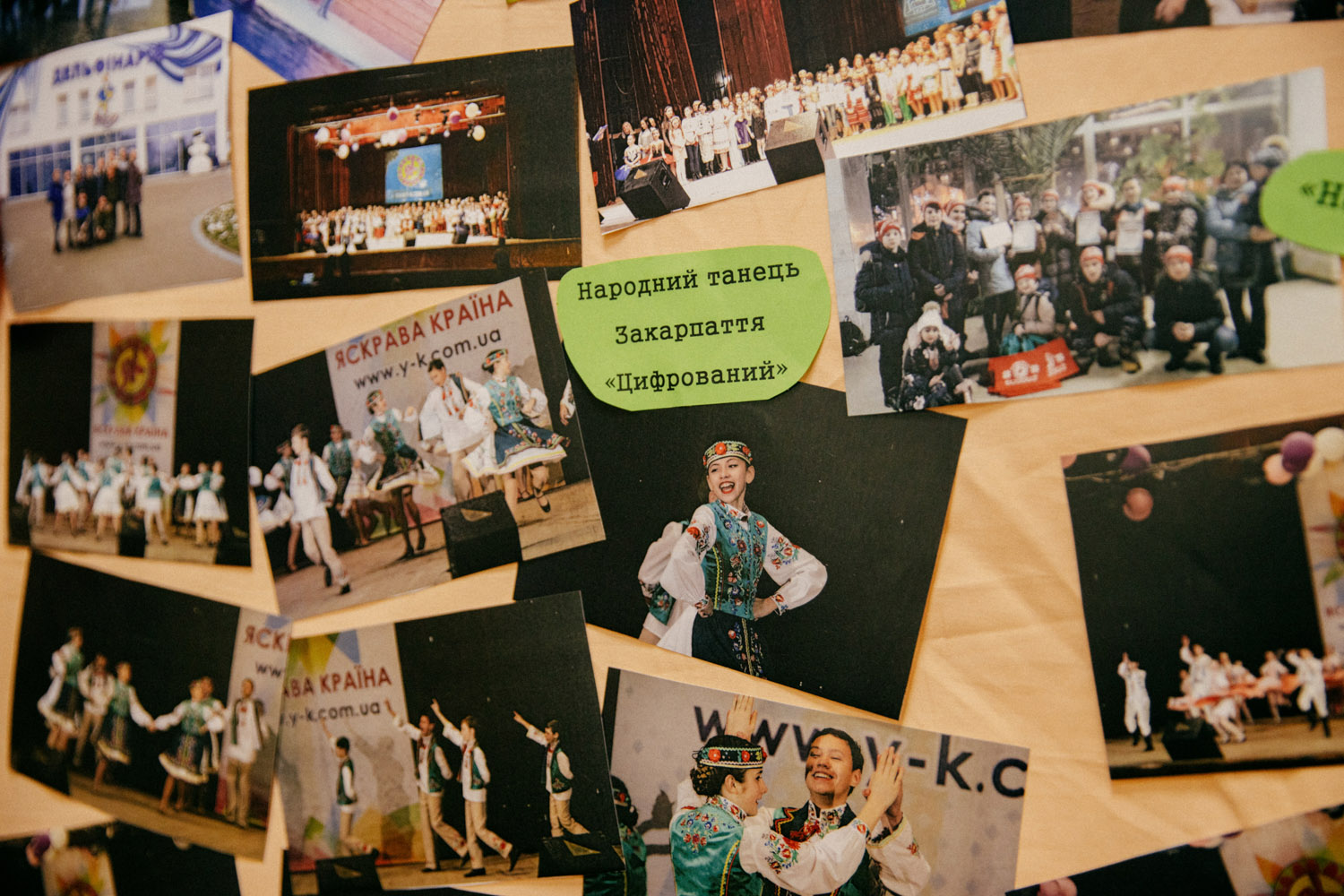

According to Myroslava’s daughter, Daryna Habor, who is now the manager of Naša Fajta, their dance troupe has been participating in various festivals and promoting Slovak traditional dance for both children and adults for fourteen years in a row:

– As soon as the harvest and work in the field were over, parents would come to pick up their children and expressed interest in dance classes: “We’d love to start dancing ourselves”. And so we started partner dancing for the parents.

One couple was followed by another until the ‘retro group’ formed, as adult members of Naša Fajta call themselves. Daryna also used to dance in the group, but these days she mostly focuses on festivals, grants, and costumes for the troupe.

During its first years, the troupe had no name and no distinct style. As soon as they defined themselves as a traditional Slovak dance troupe, Daryna began studying the nuances of folk costumes and designing their garments:

– The Ministry of Culture of the Slovak Republic together with Comenius University in Bratislava organise a summer camp for choreographers. I went there and since then I have been very interested in Slovak traditional dance.

Every year while attending the camp, Daryna deepens her knowledge and then brings back home fresh ideas for their new costumes. According to her, in Slovakia it is uncommon, even within the same region, for the traditional clothes to be the same pattern:

– Each village in Slovakia has its own unique traditional clothing, and people used to wear these clothes every day. No two skirts or waistcoats were identical. They would have the same style but different colours. And the clothing patterns and styles between two neighbouring villages were completely different from one another.

slideshow

Traditional Slovak clothing typically includes colourful waistcoats, under- and overskirts with an apron for women, and narrowed trousers for men. The garment is decorated with embroidery, strings, or lace, which are region-specific. Men wear hats with plumes, women weave ribbons into their hair or wear headscarves. The image of a Slovak woman is often associated with a wide necklace made of strings of beads:

– Many women have their own traditional necklaces and wear them at the festival to show their support of the Slovak culture, even when they don’t perform themselves, but are just the spectators.

Kids and their parents always join in to make the costumes. Some help to decorate the garment with beads, others sew on lace according to the pattern designed by Daryna. Most of this work must be done before the start of the festival season:

– We once had to stay at the club until four or five in the morning. Ten to twenty people stayed up all night for as long as we needed until we finished sewing the costumes.

Naša Fajta has become for the children much more than just a club – the house of culture is much more than just a place for rehearsals to them. They often come here to chat, to spend some time together, or to help with preparations for their next concert.

The dance troupe plays not only an important cultural role but also a social one. Not everyone in Storozhnytsia can afford to go to clubs in Uzhhorod. It requires time and money. So Myroslava and Daryna do their best to show children the world beyond Storozhnytsia. For some of the kids even their first trip to Chop was quite an event:

– For the first time, we were giving a concert somewhere else, not in our village or in Uzhhorod, but somewhere even further away. There were children who were quite excited to just see the train. “Wow! A train!” – exclaimed one of the ten-year-olds. I asked: “Have you not seen a train before?” They live right next to Uzhhorod, it’s two kilometers away. But the kid said: “Never, we’ve never left Storozhnytsia even once over nine years”.

Three years ago, Ivan Pasteliak, a choreographer famous in Zakarpattia and the head of the community of choreographers in Zakarpattia, joined the troupe. With his help, the troupe’s dancing techniques and skills improved even more, which resulted in their participation in festivals in Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Romania. Naša Fajta has even travelled to another continent. The troupe took part twice in a big international festival held in Nigeria, where they represented the Slovak culture.

In order to financially support the troupe’s travels abroad, Daryna founded a public organisation and learned how to apply for grants. Trips to Slovakia provided the opportunity for children to better learn the Slovak culture and language, which Myroslava and Daryna persistently try to preserve in Storozhnytsia. Naša Fajta has both Slovak and Ukrainian dancers. Long ago Myroslava could only speak Slovak and Russian. But these days, to her own surprise, she runs the dance rehearsals in Ukrainian while continuing to speak Slovak at home. Daryna says that the Slovak spoken here in Storozhnytsia is different from its more standardised form:

– It is not the standard Slovak language, just like Ukrainians in Zakarpattia speak in a dialect, local Slovaks here have an eastern dialect. Long ago Storozhnytsia was named Jovra, so this local dialect is called Jovranian.

Slovaks of Zakarpattia

The Slovaks of Zakarpattia are not those who happened to move from Slovakia to Ukraine, but those to whom Ukraine ‘happened’. And before then, Austria-Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic also ‘happened’ to them. The first Slovaks – the Liptaks – came as migrant workers to Velykyi Bereznyi village at the end of the 18th century. Their nickname originated from the name of their home village, Liptovská Teplička. In the 1700s, Austria-Hungary was investing in various intensive development projects. One of these projects was to expand its railway network, including a railway line that ran through Velykyi Bereznyi, and so many new jobs opened up in the area as a result.

When the First Czechoslovak Republic was formed in 1918, the second wave of Slovaks moved to Subcarpathian Rus (as the region was called back then). Those times are dearly cherished by today’s Slovaks as this was a period when their culture flourished and the economy in their villages and towns also thrived.

This was the period when Europe was just starting to recover from World War I. Large empires were crumbling and people living in territories absorbed or annexed by larger political powers were holding their breath in anticipation of the new rulers to come.

Subcarpathian Rus

The territory of today’s Zakarpattia region, which was a part of the First Czechoslovak Republic between 1919 and 1938.In 1918, the First Czechoslovak Republic formed from the remnants of Austria-Hungary and included territories of today’s Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Ukrainian Zakarpattia. At that time, Czechoslovakia was one of the most developed democratic countries and its president, Tomáš Masaryk, had a reputation as a wise leader. He initiated redevelopment of rural and urban areas, which included extending the railway network. Uzhhorod got its own airport, water supply system, and thermal power station. As a result of the agricultural reform, thousands of hectares of farmland were handed over from large landowners to families of villagers.

Czechoslovakia’s inclusive ethnic policy was a key indicator of its democratic system. The official languages were Czech and Slovak, but other ethnic minorities had enough leeway to develop their own languages and cultures. For example, in Subcarpathian Rus (today’s Zakarpattia) during that period there were 724 schools – of which 540 were Ukrainian, 130 were Hungarian, and 32 were Czech, there were also a few Romanian and German schools, and one Jewish school. For the territories of former Austria-Hungary, this was a major step forward with regard to their cultural and educational policy.

When 20 years later Subcarpathian Rus became a part of Hungary, the Slovak and Czech residents of the territory emigrated en masse. After World War II, the Soviet Union took control of Zakarpattia. The USSR reached an agreement with Czechoslovakia to allow for the repatriation of the remaining Slovaks and Czechs in an effort to permanently resolve any issues in the region related to national or ethnic identity. With the ‘issue addressed’, Slovaks disappeared from the agenda. Though many of them never moved and chose to stay at home – in Zakarpattia.

Four powers, four passports

The family of artist Michael Peter is one of many other Slovak families who over the last 150 years ended up living in several states without ever leaving their home:

– My parents and grandparents lived in four different states and had four passports, but the whole time they were living in the same place. How’s that, you wonder? They first had an Austria-Hungarian passport, then a Czechoslovakian, after that a Soviet one, and finally a Ukrainian passport.

Michael Peter often travels around Europe to attend biennales and international plein air events, he has also visited Cuba, Mexico, Argentina, and spent a year in Germany. Today he lives near the Ukraine-Slovakia border and has no intention to leave Ukraine despite the lack of financial and institutional support from the government:

– With my status as a Slovak living abroad, I can live anywhere in the EU for up to five years without even having to register. But there is no other place as good as Ukraine. This land is so blessed by the prayers of its faithful people that western countries simply can’t compete.

Michael mostly paints nature and has a special perception of colour: each colour to him is a work of art in itself:

– It’s so easy to take some expensive paint with good quality colours and do painting. But their standard colours are not good enough for me. I can keep mixing together dozens of shades and colours until I get the right one.

slideshow

As a child, he would draw mountains on the walls with charcoal before he even learned to walk. When it was time to choose where to study, Michael went to the sea. That’s how he ended up getting his degree from the Faculty of Art and Graphics at the Pedagogical University in Odesa. After graduation, Michael went to Munich for an apprenticeship:

– That year I met people from our [Ukrainian] diaspora there: famous scientists, artists, architects.

Michael is actively involved in the events of the Slovak World Congress, an organisation that represents the Slovak national community worldwide, whose members hold an annual meeting in Bratislava. After those meetings, which last a few days, Michael goes back to his most favourite of all Ukrainian cities – Uzhhorod. He especially loves the architecture from the era when it was under Czechoslovakian rule. He beams with pleasure as he speaks about it:

– All those factories, those railway stations, they built all that. The waterfront area. The craftsmanship of every house here – they tried to make them all so very special.

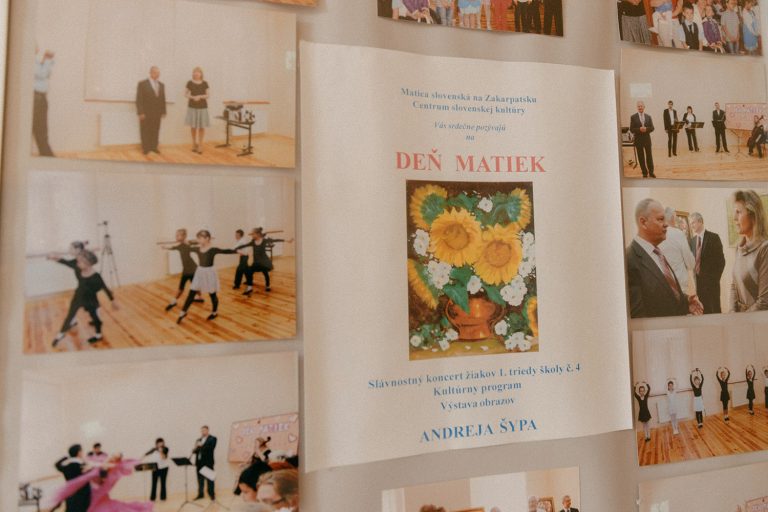

Matica Slovenská

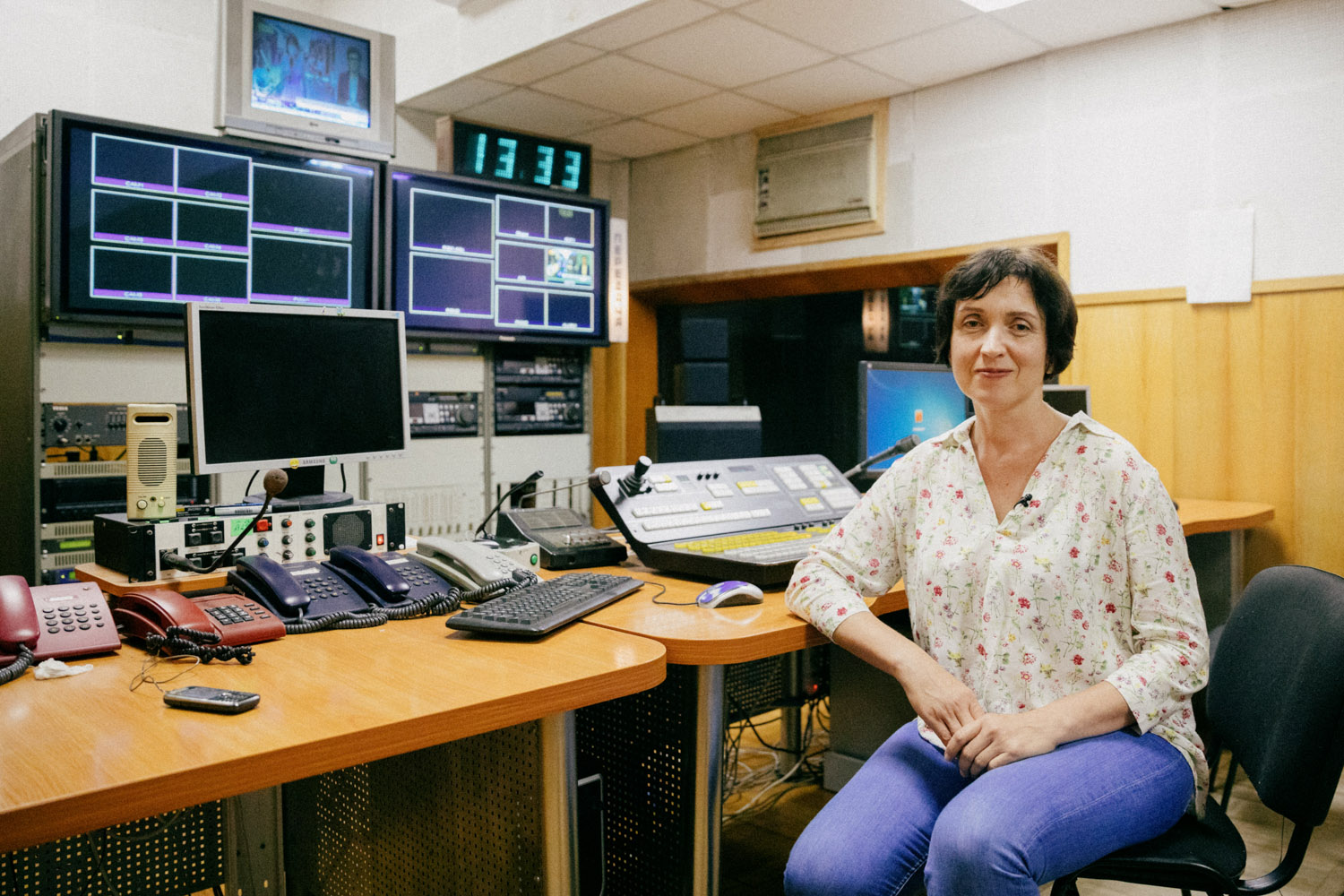

After the Soviet Union took control of Zakarpattia, the Slovak language could only be heard in a few households and in churches. When the churches were banned, the community reacted in opposition to the system, recalls Gabriela Brovdi, the editor-in-chief for the Slovak language programmes at the UA: Zakarpattia public service broadcaster:

– Even though the priests were getting arrested, and there were very few of them, people held self-organised services without a priest. Such services were called ‘dry services’. They were ‘dry’ because there was no priest and no Holy Communion.

The Slovak culture in Zakarpattia desperately needed rescue. Jozef Hajniš, ethnic Slovak, personally experienced both Czechoslovakian democracy and Soviet totalitarianism, which is why he wanted to organise a society that would preserve their community irrespective of the government’s policy. In 1992 he founded a cultural and educational organisation Matica Slovenská (‘Mother of Slovaks’) in Uzhhorod which revived Slovak traditions and united those who carried its heritage. According to the latest national census in 2001, there were 5,600 Slovaks living in Zakarpattia. The figures provided by Slovak public organisations are different – 17,000. Such a discrepancy is caused, in Gabriela’s view, by the Soviet past:

– Small number of Slovaks in the latest census stems from the fact that the Soviet Union did not recognise the existence of the Slovak community as in 1945 the Soviet government allowed the Slovaks from Zakarpattia to emigrate. Everyone who at that time wanted to or managed to leave did so. Those who stayed were officially no longer Slovaks anymore.

Gabriela grew up in Vynohradiv in a Hungarian community because her mother was Hungarian. Her father was Slovak by birth, from the village Serednie. Out of the many dialects and languages that surrounded Gabriela since her childhood, she chose Slovak:

– Probably that seed of the Slovak culture had deep roots inside me.

slideshow

Gabriela dreamed of speaking standard Slovak, which was nearly impossible in her circumstances. There was no Slovak school in Zakarpattia, and local Slovaks spoke in a dialect that mixed Slovak with the dialect of Zakarpattia. So she listened to Slovak radio, watched Slovak TV, attended additional language courses, and finally fulfilled her dream.

Today’s Slovak youth, just like Gabriela’s daughter Emilia, do not need to worry about access to cultural education. When the organisation Matica Slovenská was established, its first project was to develop Slovak language education programs throughout the region. In 2010, after some tough intergovernmental negotiations and the completion of prolonged and intensive building renovations, the first and only school offering advanced Slovak language courses opened in Uzhhorod. This was a major event for the entire Slovak community in Zakarpattia.

– When the school was about to open, my daughter was in Year 3. She said to me: “My new school will be like Hogwarts Castle from Harry Potter!”

This castle accommodates not only the school but also Matica Slovenská’s office. Because of this close proximity, students are exposed to Slovak folklore and modern art thanks to the exhibitions and events which the society runs just next door. Children learn basic Slovak and Ukrainian during their first years at school. Teachers from Slovakia are invited and only those who pass a competition are offered the job. There are even a few pilot multilingual education classes being tested where children are taught different subjects in different languages (Slovak and Ukrainian).

The Slovak editorial office

The next thing which Jozef Hajniš and his like-minded peers took care of was the media. In 1996, the regional television and radio company in Zakarpattia opened its Slovak editorial office, and Hajniš, the founder of Matica Slovenská, became its first editor-in-chief. Later he was joined by Gabriela Brovdi, who had just left school. Today she helps Jozef run Matica Slovenská and she is also the head of the Slovak editorial office at UA: Zakarpattia, a regional channel of the National Public Broadcasting Company of Ukraine (UA: PBC). Yevhen Tychyna, a producer of Zakarpattia’s branch, says that the media is trying to fully meet the needs of their multiethnic area:

– At the moment we actively collaborate with six communities: Hungarian, Romanian, Slovak, German, Rusyn, and Roma.

The Slovak editorial office includes only five people: a host, an editor, a programme editor, a translator, and a TV reporter. The team members often have to master new skills in order to keep up with modern technology and fill in any roles required by a traditional editorial office. Milan Tovt, a biologist by education, joined the office in 1999 as a radio programme editor, but later he learned filming and video editing, sharing his knowledge with the team:

– In around 2004, we began to use computer editing. Our first computer came as a donation from Slovakia. This was really something! And we realised that we were capable of doing the editing ourselves. We had to learn how to do it though, since this was all new to us, but learning something just requires a bit of time.

slideshow

The Slovak office reports on the everyday life, traditions, and events of the Slovak community in Zakarpattia. Gabriela points out that before the recent regional broadcasting policy reform, they had been covering an even wider range of topics:

– We were covering topics at various scales: from international events to, let’s say, local trifles.

At the end of 2019, the National Broadcasting Company presented its new two-year plan for its regional broadcasts, advocating that their regional programmes streamline their production approach. For example, instead of every region producing its own morning show, they should produce just one morning show that includes updates from the different regions.

At the same time, according to Yevhen Tychyna, a team was formed, whose main focus is providing and improving the media content for national minorities in Ukraine:

– Currently we actively collaborate with the Coordination Centre [of broadcasting] for national minorities, formed in Kyiv as a part of UA: PBC. The Coordination Centre proposes its own ideas for future projects to be realised, and we take part in these projects – for example we are now going to film several stories about ethnic communities.

Every week the UA: Zakarpattia channel airs the show Slovenské Pohľady (‘Slovak views’), which now, due to regional broadcasting policy changes, mostly focuses on the personal stories of the Slovak community members. Any special reports on various events are now made by a news team. The Slovak editorial office also runs two radio shows on Tysa FM, a regional public radio station.

The Slovak editorial office is the only source of information in Slovak created for and about the Slovaks of Zakarpattia, who are open to share some of their personal stories too. Once Emilia Brovdi and her classmates aired a story about a sweet treat well-known in Zakarpattia, a culinary tradition of not only Slovaks, but also Hungarians and Germans – fánky:

– On our winter holidays we hit on an idea of collaborating with the editorial office. We talked my friend’s grandma into teaching us how to make fánky. We filmed this together, and that’s why we had such a great video in the end. That granny lives in Storozhnytsia. She used to sing in a Slovak folk choir when she was about our age. She told us about the traditions she followed that had been passed down to her from her grandmother and about how things were in the olden days. And our story turned out very soulful, because we didn’t just make fánky in the end but we also talked as we had tea and sang together.

A small community of Slovaks in Zakarpattia holds firmly to their roots. While coexisting with Ukrainians, Hungarians, and other nationalities in the region, Slovaks manage to maintain their originality. That’s why the Slovak school was opened in Uzhhorod, the paintings of Slovak artists can be seen at exhibitions, and Jovranian dialect can be heard on the streets of Storozhnytsia.