To demolish or not to demolish is a debate that has been going on around soviet monuments in Ukraine since the early 2000s. On this matter, the society is usually divided into two key groups: those who want to preserve them as samples of monumental art and those who consider that they belong to the dustbin of history. Since the beginning of the full scale war, the question of soviet monuments has become even more fundamental. In this article, we will explain why Ukrainians should get rid of the Russian cultural monuments forever.

A monument, a monumental plaque or a memorial are concepts that refer to monumental objects of different shapes and materials. But their common key function, which has not changed since their emergence, is to immortalise important places, events and (or) figures that influenced the life of a society in the country where they are installed. However, history shows that this main function of memorials works as a good shield which can hide propagandist intentions.

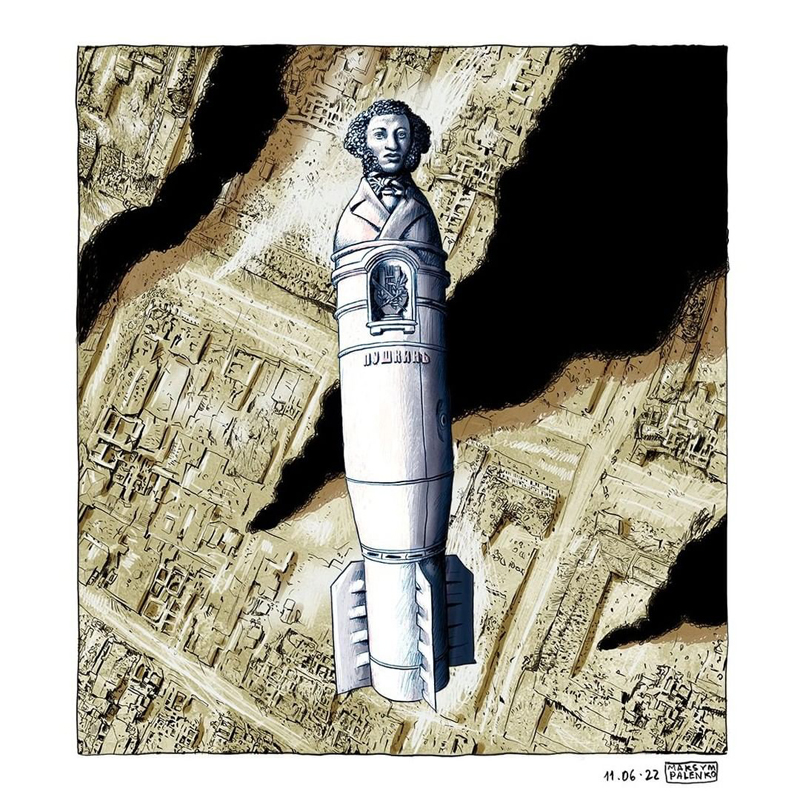

Illustration: Maksym Palenko.

Russia was especially distinguished in this sense. Having signed the decree “On the Monuments of the Republic” in April 1918, Lenin unleashed monumental propaganda (he proposed the name himself), making it a matter of state importance. Instead of monuments to tsars and servants of the Russian Empire, it was ordered to urgently erect monuments to the leaders of the socialist revolution everywhere. The Bolsheviks had no intention of creating long-lasting monuments with an artistic value. The leader’s idea was implemented in a hurry, because the main goal was to “mark” the territories with monuments to the representatives of the new government instead of monuments of tsarist Russia. Sometimes, such terrible specimens were produced that they were dismantled just as quickly, so that their appearance would not discredit the leaders of the party.

Although there was an order to dismantle monuments to Russian tsars and their assistants, there are some that stood (or were “reborn”) to this day. For example, the monument to Catherine II in Odesa was dismantled in 1920, but its exact copy was installed in 2007. Since the beginning of the 19th century, Russian figures of culture and art, such as numerous Pushkins, Dostoevskys, Tolstoys and others, have not been thrown off their pedestals in Ukraine. What is wrong with them and why is it time to clean the public space of Ukraine from them?

Argument 1. Monuments as an instrument of mythmaking

Monuments immortalise not only the persons embodied in them, but also their ideas. In the background of socio-economic problems, installing some monumental objects can look innocent or even pass by people’s attention; however, this is an especially effective tool of influence. Erecting monuments, memorial plaques, and so forth helps to instil in the society an idea like “if it was installed here, then it’s important.”

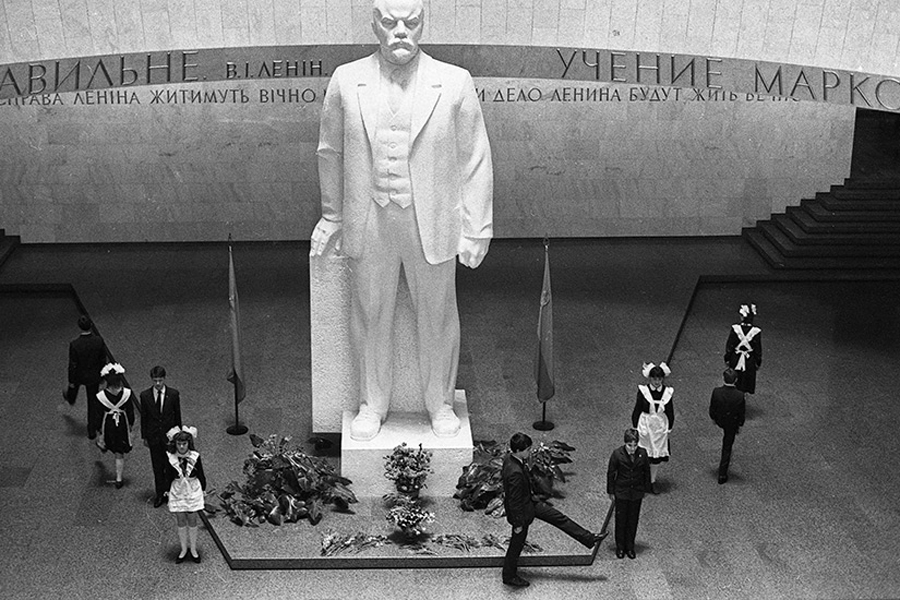

Photo: Viktor Marushchenko

Lenin and Stalin understood it very well. Their monuments were erected in almost every single settlement both during their lifetime and after their death. For example, there were almost 7 thousand monuments to Lenin in the territory of soviet Russia and more than 5 thousand in Ukraine (these are approximate numbers according to the data from 1991 as there were no completely clear records of such monumental objects). Sometimes, a few monuments could be noticed on the same street. For example, there were three Lenins on the main street of Kyiv in the soviet times, although he had never been in Kyiv. The first “leader” was on Taras Shevchenko boulevard (in front of the Besarabskyi market) from 1946 to 2013. The second one was on the main square near today’s Hotel Ukraine (Hotel Moscow at that time) from 1977 to 1991. The third one was located in the building of today’s Ukrainian House, which used to be Lenin’s museum from 1982 to 1993 (the monument to Ilyich stood there for the same amount of time, until it was dismantled). By the way, Lenin in the Bessarabska square started “Leninfall”. It is symbolic that one of the main executioners of Ukraine stood on the place where Nazis made demonstrative mass executions on the gallows during World War II. Granite Lenin was stripped from its status as a monument of national significance within 18 years after Ukrainian independence. The place where the monument was located became not only an artspace for temporary installations but also a symbol of civil society’s close attention to the government’s actions.

“Leninfall”

A wave of mass demolition of monuments to Vladimir Lenin and other communist and soviet figures erected on the territory of Ukraine. The concept was coined during the Revolution of Dignity (2013-2014), even though such objects were dismantled before.

Photo: Ukrinform.

Mass reproduction of monuments to the leaders was termed in Ukrainian history as Leniniana and Staliniana. Putin, by the way, does not seem to reject monumentalist propaganda, thus we can surely talk about Putiniana. Such a number of monumental objects of the same type preserved the loyal or indifferent attitude of Ukrainians to communism and its representatives for a long time because different types of “leaders” stood in different regions of Ukraine many years after gaining independence. Even after the decrees of the President of Ukraine Viktor Yushchenko in 2008-2009 on the dismantling of totalitarian monumental symbols dedicated to persons involved in the organisation and implementation of the Holodomors, there were hundreds of monuments to persons whose regime killed many people throughout the country. In just 70 years (1917–1987), almost 100 million people in the world became victims of communism.

Decree on the dismantling of totalitarian symbols

Decree № 432/2009 "On additional measures to commemorate the victims of the Holodomor of 1932-1933 in Ukraine", Decree № 250/2007 "On measures related to the 75th anniversary of the Holodomor of 1932-1933 in Ukraine" Decree № 856/2008 "On measures in connection with the Remembrance Day for the victims of Holodomor”.

Besides commemorating an individual or forming his cult, memorial buildings were used as an instrument for creating larger narratives, particularly state narratives. Not only is the Soviet Union known for this, for instance, Hitler used Tannenberg National Memorial, where Reich President Paul von Hindenburg was buried, in order to popularise the Third Reich. This grand memorial building, built in the 1920s as a memorial to Germany’s victories in the First World War, was exploited to form new ideas about new German society and how it should behave. German authorities even issued special instructions regulating holiday celebrations on the site and near the memorial. Particularly, it was forbidden to hold any events except those commemorating the deceased in the World War and those perpetuating the memory of the president. The building existed for only 18 years. Hitler ordered to blow it up so that the advancing Red Army would not capture it. However, this memorial building had completely fulfilled its ideological and mythmaking function. It was part of a narrative that the Battle of Tannenberg (known as the Battle of Grunwald in Polish and Russian discourse) was the alleged historical revenge of Germans against the Slavs for the events of 1410.

Argument 2. Monuments сan’t be outside of politics

The soviet monuments still remain a trump that some political forces use at the right moment to increase the sympathy of their voters. Perceptions of any memorial building are short-sighted and a little naive due to its exclusively cultural interpretation. While discussions about the need for some or other monuments are taking place at the local level (this is at best, because this issue is often considered as “out of date”), Russia even uses memorial buildings to incite enmity between countries.

A famous case is the Monument to the Liberating Soldier from the times of World War II in the capital of Estonia. In 2007, the government decided to move it from the Centre of Tallinn to the Military Cemetery, as well as to rebury the bodies of unknown soldiers. Russian-speaking activists incited clashes around this monument as early as 2006. Thus, Estonian parliamentarians passed a law on the protection of military graves in 2007. It involved the reburial of the soldiers’ remains to more appropriate places.

Russia immediately got involved, interpreting the incident as an insult to the memory of the fallen in the Second World War. The Bronze Soldier almost became a cause of breaking diplomatic relations between the countries (yes, such statements were made by Russian authorities). However, the problem went beyond the negotiations of high-ranking officials. First, 60 people (now we would call them titushky) protested near the Estonian embassy in Moscow against the relocation of the monument on April 27, in Tallinn. They blocked the exit from the building to Marina Kaljurand, then the Ambassador of Estonia to Russia. The same day, at night, a demonstration of one and a half thousand people took place which resulted in wrecks and looting. Demonstrators protested against the relocation of the monument and the reburial of the fallen soldiers’ remains. One protester died that night and about 50 were injured (both protesters and policemen). Nevertheless, Estonian authorities did not change their “monumental decision”, probably understanding that having allowed such an interference from Russia at least once, it would be repeated again and again. Toomas Hendrik Ilves, the Estonian president at that time, stated very clearly: “… in our minds, this soldier represents deportations murders, and the destruction of the country, but not liberation.”

Photo: Liis Treimann.

Of course, a monument is just a good excuse behind Russia’s desire to at least somehow influence the politics of former USSR countries. This “bronze story” could be lost in the news feed, but it became very revealing in the context of the cultural expansion policy of Russia, which seeks to somehow influence the agenda in other sovereign countries. In addition, some historians claim that the events around the monument in Tallinn were a rehearsal for the events in Ukraine. In this way, Russian propagandists tested how the ideas of the “Russian World” would take root and how the society would react to their prepared messages justifying any criminal actions. Currently, Russia is staging another act of the theatre of the absurd. It is erecting monuments to Lenin in temporarily occupied Ukrainian cities and villages (for example, in Henichesk, Nova Kakhovka, and Novopskov). And in the Smolensk region, where the Katyn Memorial stands (erected in memory of the mass executions of Poles in the 1940s, known as the Katyn Massacre), Russia is “plays” with Poland, showing its intention to demolish the object.

By the way, a monument to Russia can be erected for another “ingenuity”. Particularly, there is an article in the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation stating responsibility for the destruction or damage of various memorial structures that perpetuate the memory of the World War II not only on the territory of their country, but also outside its borders. A fine, three years of penal labour or years of imprisonment is what one can get for such actions.

Argument 3. Monuments are a marker of physical and cultural space

One of the instructions that concludes the book “Visual culture” by the researcher Alexis L. Boylan highlights the question of what exactly should be in the public space. “We must know how visual cultures are being created and carefully monitor what exactly we visually consume the whole day. We must know what influences, prejudices and stories are embedded in the images and objects. We must be able to perceive some of them and to reject others.” It’s important to remember that any monumental object, installed either in a city or a village, defines the toponymy of the space for many years ahead.

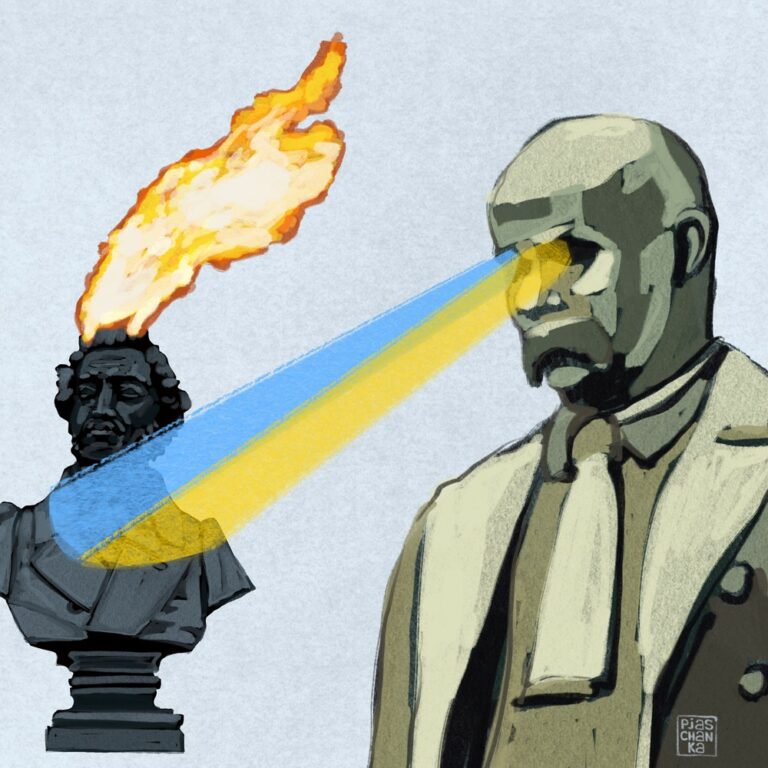

Illustration: Viter Stepovyi

It means that if, let’s say, there is a monument to Pushkin in the centre of a settlement, the whole thing is not limited by only a several dozen-metre statue. His name appears on all maps and street signs. On the place where a monument to Pushkin is, a park named after him “grows” quickly. And all these names roam in a number of official documents, private correspondence and conversations. In this way, the attitude towards controversial figures of Russian culture, which for centuries has swept under Ukrainian culture, is being imperceptibly normalised. For example, the first monument to the Ukrainian writer Ivan Kotliarevsky appeared at the beginning of the 20th century, four years after the first monument to Russian Pushkin was erected, which is quite predictable. In addition, the inscriptions on the monument to the “father of new Ukrainian literature” were in Russian, which was dictated by the Ems Decree.

Illustration: Maksym Palenko.

Every memorial building to a Russian cultural figure in Ukraine is a displacement of Ukrainian figures who actually deserve to be in their place. It is a materialised cultural code embodied in a monument, memorial plaque or memorial complex. And who we choose to see in the squares of our towns and villages determines how we identify ourselves and what is valuable to us.

With the start of the full-scale war with the Russian Federation, the “monumental issue” has made some progress: more than 70% of Ukrainians support the dismantling of structures associated with the aggressor country. However, 40% are against the demolition of monuments dedicated to the World War II. It seems that now is the time to talk about the fact that dismantling monuments does not mean forgetting history, but rather reinterpreting it. And now is probably the best time to finally eradicate foreign Russian elements from the landscape of Ukrainian cities, villages and culture.

Russia shouldn’t shape the memory policy in Ukraine. It has been conquering and subjugating Ukrainian culture, as well as trying to steal and distort Ukrainian history. Military crimes committed by this aggressor state should not leave any sentimental feelings towards any object of the Russian manipulative soviet monumental culture that still stays in Ukrainian cities and villages. Destroyed objects of military and civil infrastructure of Ukraine are the “monuments” that “the grand culture of Ruzzia” leaves.