The crimes committed against humanity that become known globally certainly influence moral narratives across borders and geographical barriers. They point to the limits of humanism and human decency. This way guiding principles are established in a form of common history from different perspectives and the integrated experience that affects everyone involved. The Holodomor genocide is a lesson that Ukraine and the rest of the world are yet to fully fathom and integrate into the local consciousness.

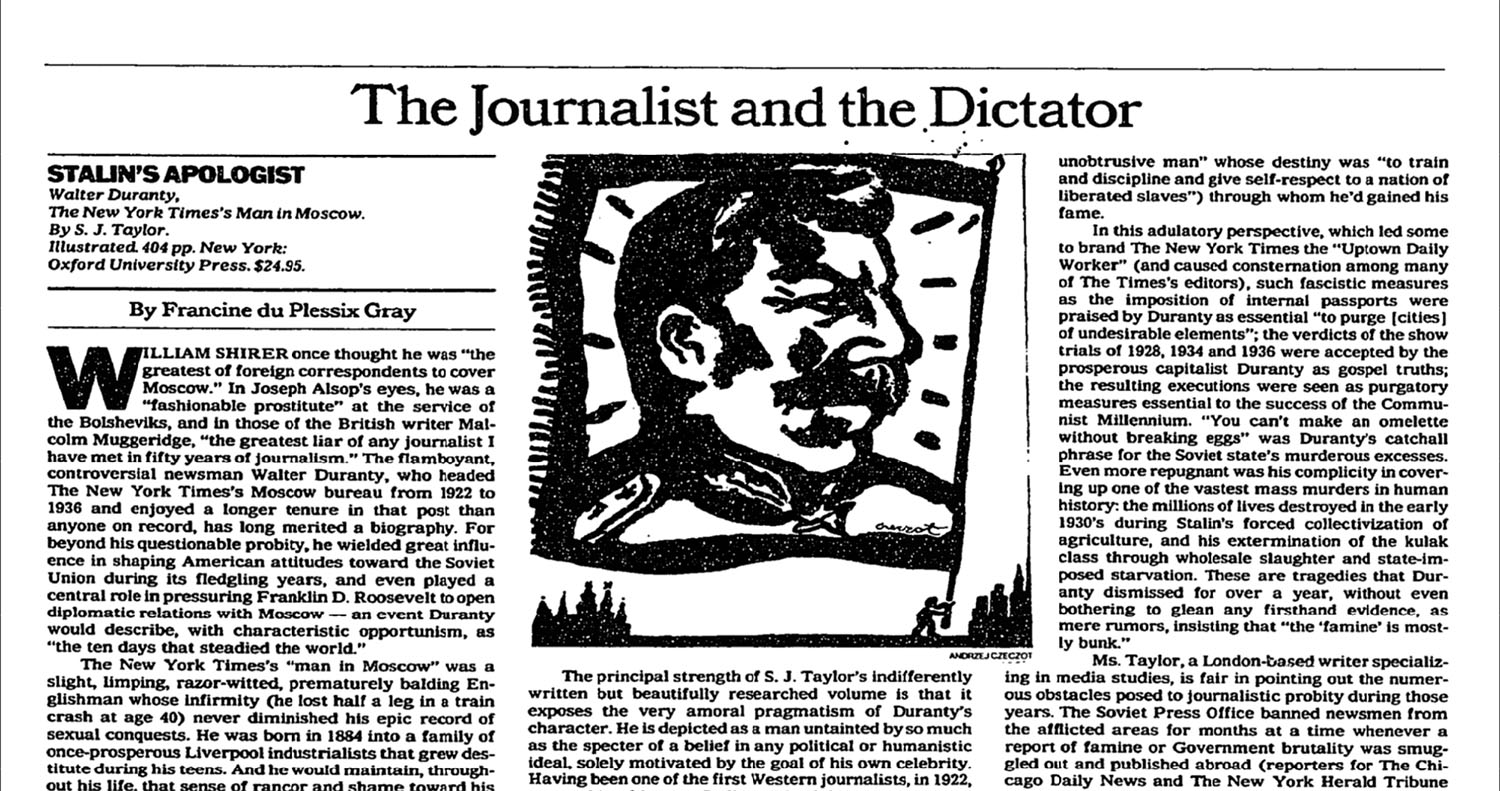

The New York Times, 24 June 1990.

The truth vs. the Pulitzer Prize

At the beginning of the 20th century, Annie Gwen Jones became an active member of the suffragette movement in England, right after returning from a far-away Yuzivka where she worked as a governess for John Hughes’s family. Her son Gareth was born in 1905, and her tales and stories of far-away parts of what was then the Russian Empire, became part of his childhood. Inspired by his mother’s stories about the beautiful land, he dreamt and hoped of visiting it since childhood. He attended Cambridge where, in addition to other subjects, he studied Russian. At that time, Gareth, a highly educated young man who was fluent in five languages and had the prospect of a brilliant career in politics, had no idea that he would never be able to see Yuzivka, but instead Stalino, as it was renamed. Instead of seeing a successful industrial city, he came upon an impoverished population, destroyed by famine. And he had to give his life for the truth and become the voice of millions of silent victims of Stalin’s regime.

A somewhat different story was unfolding for another Cambridge graduate. At the time when Gareth was only dreaming about a cherished ticket to Russia, Walter Duranty’s name had already blown up in the Western world. In 1929, as a New York Times correspondent, he became the first Western journalist to interview Joseph Stalin. He moved to the USSR in 1921. Before that, during World War I, he worked as a New York Times reporter, and after the war he stayed to live in the USSR. As a foreigner who lived in Russia for such a long period of time, in the Western world he gained respect as an expert in everything related to communism and the closed off and difficult-to-comprehend Soviet Union. By 1931, the well-known reporter Duranty had published thirteen articles about the USSR. His views surprisingly lined up with the official Kremlin position, highly valued by Stalin himself. This fact alone speaks volumes. However, this did not prevent him from receiving the Pulitzer Prize and recognition for saying the following:

“Stalin is giving the Russian people — the Russian masses, not Westernised landlords, industrialists, bankers, and intellectuals, but Russia’s 150 million peasants and workers — what they really want, namely joint effort, communal effort.”

Yuzivka

Yuzivka was the name of the Ukrainian city of Donetsk up to 1924 and in 1941–1943. In 1869, a Welsh engineer and businessman John Hughes came to those places and started building a metallurgic plant. The place was called upon his name — Yuzivka (or Hughesivka). Later, Yuzivka was renamed to Stalino to honour steel industry (“stal” is the Ukrainian word for “steel”). This city’s name was also close to the surname of the USSR’s leader — Joseph Stalin. In 1961, the city was renamed to Donetsk, as it is situated in the area of the Donets Ridge and the Siverskyi Donets River.

Ukrainian-language newspaper “Svoboda” (Freedom), Jersey City, USA, 15 February, 1932.

Eventually, in 1933, during the very peak of the Holodomor, the paths of these two people crossed, turning them into the main voices that informed the world about the event in Ukraine.

On 15 February 1932, a Ukrainian-language newspaper “Svoboda”, based in Jersey City, U.S.A., published an article entitled “Moscow wants to starve Ukrainian villagers to death”. In 1933, more articles were published about the famine in the USSR almost weekly. On 23 February 1933, the USSR issued a resolution that forbade foreign journalists from leaving cities.

In March of 1933, Gareth Jones broke this resolution by purchasing a train ticket to another city, leaving the train before his final destination and travelling in Ukraine, going from village to village.

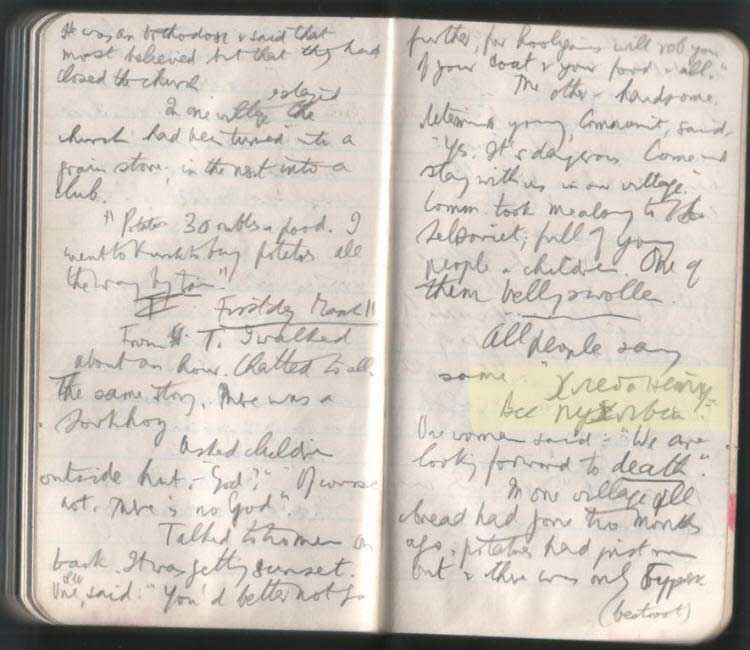

An excerpt of Gareth Jones’s first diary, written during his 1933 visit to the USSR.

“I walked along through villages and twelve collective farms. Everywhere was the cry, ‘There is no bread. We are dying.’ This cry came from every part of Russia, from the Volga, Siberia, White Russia, the North Caucasus, and Central Asia. I tramped through the black earth region because that was once the richest farmland in Russia and because the correspondents have been forbidden to go there to see for themselves what is happening. In the train a Communist denied to me that there was a famine. I flung a crust of bread which I had been eating from my own supply into a spittoon. A peasant fellow-passenger fished it out and ravenously ate it. I threw an orange peel into the spittoon and the peasant again grabbed it and devoured it. The Communist subsided. I stayed overnight in a village where there used to be two hundred oxen and where there now are six. The peasants were eating the cattle fodder and had only a month’s supply left.”

The winter of 1932 to the summer of 1933 was the peak of what would later be recognised as the genocide of the Ukrainian people. In attempts to break the resistance of Ukrainian villagers against collectivisation and the unrealistic grain procurement plans, the Soviet government first took away all grain, then all food, and then limited the ability to travel inside the country. At first, the villagers did not have any documentation and were not allowed to purchase train tickets without permission from the head of the kolhosp (the collective farm). Later, in 1933, even this was forbidden. The villages essentially turned into cemeteries. To make the situation even worse, there were “black boards”, or “boards of infamy”: if a village was added to it, it was blamed for failing the grain procurement plan and was doomed. Jones, once in love with the far-away industrial land, saw death, destruction, and total starvation with his own eyes.

In the same March of 1933, the journalist Malcolm Muggeridge published three analytical articles in The Manchester Guardian about the famine in Ukraine, for the first time in the Western press. The same newspaper later published Gareth Jones’s article “Famine in Russia”, specifically about the situation in Ukraine. On 29 March, Jones held a large press conference in Berlin, where he described the actual situation in the USSR to the general population. His words spread to European newspapers. On 31 March, Jones published his article “Famine Rules Russia” where he clearly showed that the famine affected specifically defined regions. While Moscow was feasting, Ukrainian villages were dying:

“The Five-Year Plan has built many fine factories. But it is bread that makes factory wheels go round, and the Five-Year Plan has destroyed the bread supplier of Russia.”

On the same day, 31 March, The New York Times was “graced” with an article stating the opposite: “Russians are hungry, but not starving”, by Walter Duranty. The article was written by an “expert” who had lived for ten years in a closed and unknown country, that was building communism. Many considered communism a better option than “rotten” capitalism and the Great Depression. The article that was written by a Pulitzer Prize winner, respected even by President Franklin D. Roosevelt himself, prevailed over the voice of an unknown Welshman. The general public chose authority over truth:

“To put it brutally — you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs, and the Bolshevik leaders are just as indifferent to the casualties that may be involved in their drive toward socialism as any General during the World War who ordered a costly attack in order to show his superiors that he and his division possessed the proper soldierly spirit. In fact, the Bolsheviki are more indifferent because they are animated by fanatical conviction”.

Duranty stressed that there were indeed problems with food supply in the USSR, but not as severe as Jones described. In the same manner, he justified the Soviet leaders and politics and called the millions of people who died simply a running cost on the way to progress and prosperity. This is what Stalin said of Duranty, “You did a good job in your reports about the USSR. Even though you are not a Marxist, you try your best to tell the truth about our country”. It could only mean one thing: Duranty played the same role in sending millions of deaths into oblivion as did Soviet propaganda.

Vitalii Portnikov, a journalist. Photo by Oleh Pereverzev.

“It was the time when the Western intellectuals were choosing between Bolshevism, democracy, and Nazism. Of course, most people would want democracy. But even the people who wanted democracy believed that Bolshevism was an ally in the fight against Nazism” (Vitalii Portnikov).

In the autumn of 1933, the U.S. recognised the USSR. In that same fall, in a private conversation with the diplomat William Strang, Duranty said, “It is very probable that no fewer than 10 million people died in the Soviet Union over last year.”

In 1935, Jones died under unknown circumstances. The authority of the Pulitzer Prize fame triumphed, burying millions of Ukrainians together with Gareth.

Breaking the silence

Some mentions of the Holodomor appeared during World War II. The Nazis, invading the USSR in 1941, did not ignore the historical fact of the Holodomor. They did not uncover it out of pure intentions but for the sake of undermining the authority of communism. However, due to the active state of war and the fact that the Holodomor was mentioned by representatives of another totalitarian regime, it did not affect the global silence. Additionally, the USSR as the winning side was able to dictate its rules to the world: a taboo on memories.

The first ones to speak up about the famine and the crime of the communist totalitarian regime were members of the Ukrainian diaspora. It was mostly eyewitnesses of the Holodomor who managed to escape abroad. For example, Ostarbeiters were workers forcefully moved to Germany during World War II and ended up staying in Western countries such as the United Kingdom, West Germany, France, and the U.S. after the war. These people were able to freely speak about the Holodomor and the repression they experienced in the USSR.

Viktoriia Horbunova, a psychologist. Photo by Valentyn Kuzan.

“They moved, but they came together there. They established community centres and built churches there and had spaces for communicating together. And they talked. They shared stories. It was something that we did not have. They read Ukrainian books and did their best to keep their identity. They are fairly integrated, but at the same time, the communities still exist thanks to these stories. It is the stories that create reality.” (Viktoriia Horbunova, a psychologist.)

In the 1950s and 1960s, there were some works about the Holodomor published in the U.S. and Canada. For example, The Black Deeds of the Kremlin: A White Book, a two-volume reference book published in Toronto in English, or The 1933 Famine in Ukraine: Eyewitness Testimonies about Moscow’s Extermination of the Ukrainian Peasants by Yurii Semenko published in New York. In 1962, also in New York, the first volume of Vasyl Barka’s novel Yellow Prince came out, and is still one of the most well-known fictional stories about the Holodomor events. At that time, the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies in Edmonton, Canada, operated, as well as The Ukrainian Research Institute, Harvard University, founded by Omeljan Pritsak.

At the same time, Ukrainians in exile used the Holodomor anniversary to spread awareness of the Soviet crime. The 50th anniversary was memorable as it pushed the topic from exclusively Ukrainian to a global political level.

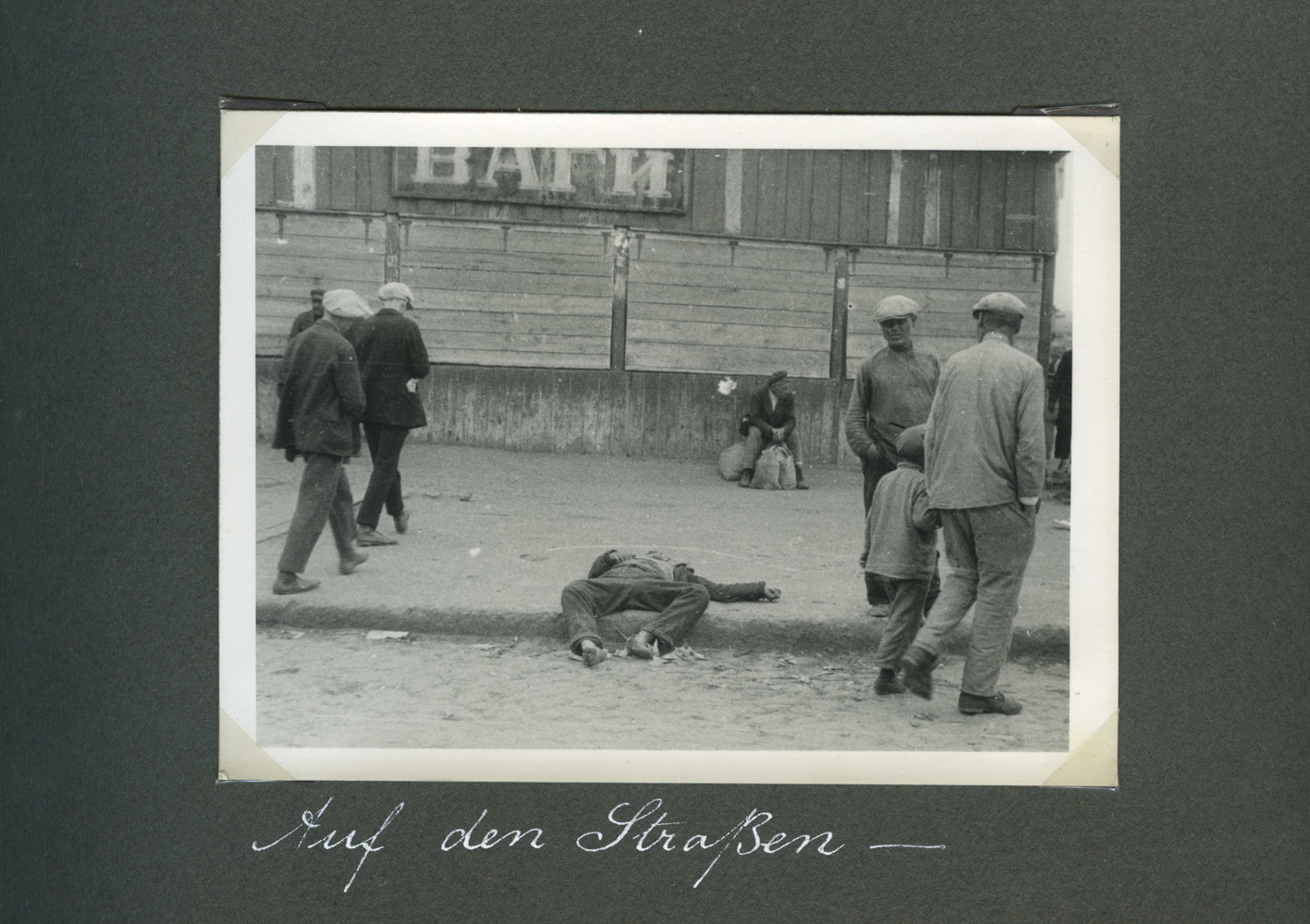

Starvation in the streets of Kharkiv, 1933. Photo taken by A. Wienerberger. Photo documents were provided by his great-granddaughter, Samara Pierce.

Your dead chose me

In 1983, Bohdan Krawchenko, S. Maksudov, aka Aleksandr Babionyshev, James Mace, and Roman Serbyn spoke at the Scientific Conference at the University of Quebec. Attention to the events in Ukraine in 1932–1933 grew on different levels. The representatives of the USSR and Ukraine in the UN were forced to escape from Western journalists and keep silent in response to multiple questions about the famine.

In 1984, Ihor Olshaniwsky, the head of an organisation called “Americans for Human Rights in Ukraine”, with the support from U.S. Senator Bill Bradley and Congressman James Florio (both from New Jersey), initiated a committee in the U.S. Congress. It studied the Ukrainian famine of 1932–1933 and spread this knowledge all over the world, ensuring a better understanding of the Soviet system by the American public through distinguishing the role of the Soviet government.

Ihor Olshaniwsky studied the archives of the Holocaust committee in the U.S. Congress and proposed creating a similar committee to study the Holodomor. James Florio and Bill Bradley supported the idea. In November 1983, Florio introduced in the House of Representatives a bill about creating a committee in the Congress, which was signed by 59 Representatives. In March 1984, Senator Bradley introduced a similar bill to the Senate. There were no obstacles in the Senate, thanks to the influence of Ukrainian National Association Vice President Myron Kuropas, although the Foreign Affairs Committee in the House of Representatives never passed the bill. On 4 October 1984, the last day of work for the Congress, Bill Bradley, using his right as a senator to amend the budget, added expenses to the Financial Resolution for a temporary committee dedicated to studying the Holodomor. As it was the final day of work, there was no time for discussion, otherwise the U.S. would not have a set budget for 1985. The House of Representatives accepted the addition.

On 12 October 1984, the U.S. President Ronald Reagan signed the Financial Resolution that began the work of the committee. It was led by Representative Daniel Andrew Mica. The working group for data collection was led by James Mace, of the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. He later became the executive director of the committee. In April 1988, the committee came to a conclusion. Based on eyewitnesses’ testimonies, they found that the Holodomor was, in fact, a genocide. Mace’s research was based heavily on recollections of eyewitnesses. However, the committee was not able to provide a legal assessment of the events.

Therefore, the Ukrainian World Congress initiated the International Commission of Inquiry into the 1932–33 Famine in Ukraine, led by Jacob Sandberg. In 1989, the Commission stated the reasons for the famine: the unrealistic grain procurement plan, forced collectivisation, dekulakisation, and the desire of the central Soviet government to defeat “traditional Ukrainian nationalism”. The Commission upheld the ethnic element of the Holodomor and most of the members considered it a genocide.

DEKULAKISATION

A form of repression against Ukrainian villagers, which included eviction and confiscation of all property, labelled as the so-called “class struggle against kulaks”, the well-off villagers.

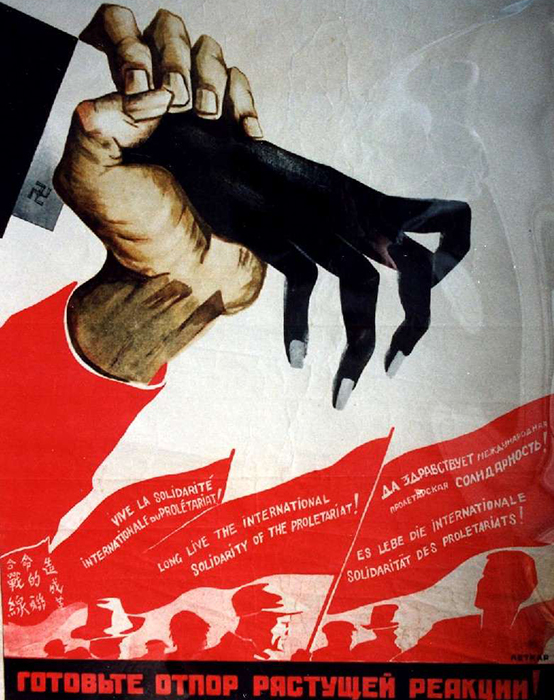

“Preparing Resistance to Growing Reaction”, by Letkar. Photo from Gareth Jones’s collection of Soviet political campaign posters purchased during his visit to the Soviet Union in 1931.

“The road to worldwide October (revolution) — Hoover Plan — Crisis”, by Victor Deni. Photo from Gareth Jones’s collection of Soviet political campaign posters purchased during his visit to the Soviet Union in 1931.

Additionally, the Commission made one more important conclusion. There is a premise that since the law is not retroactive and the 1948 UN Convention came later, the Holodomor could not be recognised as a genocide. However, the Commission pointed out that the Convention does not fall under the criminal law definition, and therefore is retroactive. Therefore, in legal terms, based on the Commission’s conclusion, the Holodomor could be considered a genocide.

The Commission agreed that since the USSR intended to destroy the Ukrainian population, it “considers it justified to think that the genocide against Ukrainian people did happen and contradicted the norms of international law in force at the time”.

In 1986, thanks to the materials gathered by James Mace, Robert Conquest published a book called The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivisation and the Terror-Famine, which became a bestseller. Later, Mace wrote, “My fate is such that your dead chose me.” Starting from 1993, he lived in Ukraine. In 2003, with the assistance of James Mace, The Holodomor Victims Remembrance Day was established in Ukraine. On the last Saturday of November, candles glow in windows, lit in remembrance of grandparents, parents, brothers, sisters, and friends who died in the genocide. Until his death in 2004, the researcher kept publishing articles in the newspaper “Den” (“Day”) and worked at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. In November 2005, the Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko posthumously awarded James Mace with The Order of Prince Yaroslav the Wise.

Dropping the Iron Curtain

“The Soviet Union actually didn’t know what to do. Because the information spread all over mass media. Soviet people did not read the Western press but they listened to radio ‘Svoboda’. The USSR needed to counteract that propaganda.” (Roman Podkur).

On 25 December 1987, in the report dedicated to the 70th anniversary of the creation of Soviet Ukraine, the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine Volodymyr Shcherbytsky finally admitted the fact of the famine in 1932–1933. However, the communists talked about natural reasons for the famine, particularly drought. They understated the extent, and refuted the fact that it was man-made and planned. It happened when the Congress Commission had been already working in full force. Soviet historians received access to the archives for the first time. Many of them were brought up by the communist system with limited access to original sources and had to completely rebuild their worldviews.

Roman Podkur, a historian. Photo by Oleh Pereverzev.

“All of our teachers who received access to the Communist party archives where the number of victims in the Vinnytsia region was documented, they began pondering: if the report shows that there are 287,000 deceased in just 17 districts of this region, how many deceased must there be in all 79 districts?” (Roman Podkur).

In Ukraine, two of the first researchers of the Holodomor were Volodymyr Maniak and Lidiia Kovalenko. They began their work in 1987, when the access to archives was opened for Soviet historians. In 4 years of work, the researchers found noteworthy documents and recorded statements of over 6 thousand eyewitnesses of the Holodomor in Ukraine. Over a thousand of them were included in the “People’s Book-Memorial. 33rd: Famine” which came out with a dedication “to the memory of millions of Ukrainian villagers who died a martyr’s death by starvation, caused by Stalin’s totalitarianism, and to the memory of thousands of Ukrainian villages and hamlets that were wiped from the face of the earth in the biggest tragedy of the 20th century.”

In 1992, Volodymyr and Lidiia initiated the creation of the Association of the 1932–1933 Holodomor Genocide Researchers, of which Lidiia was the head. Thanks to the efforts of a small group of researchers and former dissidents in Ukraine, the topic of the Holodomor was not only unveiled from the archives but studied actively. It was now mentioned not only overseas, but in local Ukrainian scientific publications, which signalled a new turn in the process of Ukrainians understanding and comprehending their own history.

In June 1992, in the village of Tymoshivka in the Cherkasy region, one of the first memorials to the Holodomor victims was dedicated. On their way home from the event, the couple was in a car accident, and Volodymyr died instantly. Lidiia passed away from injuries half a year later. They were both posthumously awarded with the Shevchenko National prize, and in 2005, Volodymyr Maniak was awarded with The Order of Prince Yaroslav the Wise.

Despite the tragedy, the Association of Researchers continued their work. They focused on commemorating the Holodomor victims, creating lists of the starved, installing memorials, crosses, and monuments on the mass graves of the genocide victims.

On 10 December 1994, a politician and dissident Levko Lukyanenko became the head of the Association. Between 21 December 1996 and 22 May 1998 it was headed by Vasyl Marochko. Levko Lukyanenko became an honorary chairman and on 22 May 1998, he again became its head.

In 1998, the Association settled on the name “Ukrainian Association of Holodomor Researchers”. During the same conference the organisation demanded that the Supreme Council of Ukraine set a Memorial Day for the 1932–1933 Holodomor Genocide Victims.

At first, the commemoration of the Holodomor victims and awareness was spread by the general public. In 2006, during Viktor Yushchenko’s presidency, when the Holodomor was recognised as a genocide by the Ukrainian Parliament, the topic of Holodomor became a priority in governmental politics, an important part of national memory and of external politics. Thus, the 75th anniversary was commemorated on a governmental level with the participation of foreign delegations. The Memorial for the Holodomor Victims was also built and currently, the second part of the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide is under construction.

Oksana Zabuzhko, a writer. Photo by Oleh Pereverzev.

“What stands in the way of the topic of the Holodomor is the way it was preserved in a certain time frame, on a historical shelf. As if the Holodomor just came and went. In 1932 and 1933, a number of people died, but we do not know the exact figure, and it is expected that after 3 or 4 generations it will be almost impossible to establish the exact number, which is macabre in and of itself — how many millions? And it came about in generations that lived in the same century! The discussion about the Holodomor, both in Ukraine and globally, stops here. It ends up looking as if it all belonged in the past. ‘That’s history,’ as Americans would say in such instances” (Oksana Zabuzhko, a Ukrainian writer).

In May 2009, the Security Service of Ukraine opened proceedings “On the fact of committing genocide in 1932–1933”. The investigation confirmed that the leaders of the Soviet Union had the intention of wiping out a part of the Ukrainian nation. It became the main basis for recognising this crime as a genocide.

“The pre-trial investigation established irrefutable evidence of conscious intent of Stalin (aka Dzhugashvili), V. M. Molotov (aka Skryabin), L. M. Kaganovich, P. P. Postyshev, S. V. Kossior, V. Y. Chubar, M. M. Khatayevich, to bring about the physical destruction of a part of the Ukrainian (but not any other) national group, and it has been objectively proven that this intent applied specifically to a part of the Ukrainian national group as such.”

The Kyiv Court of Appeal gave special attention to the question of the retroactive effect of the Article 442 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine. Based on Article 7 of The European Convention on Human Rights of 1950 and Article 1 of the UN Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity of 1968, the Court ruled that “there are no legal restrictions to apply Part 1 of Article 442 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine retroactively” towards actions of persons that committed a crime of genocide in Ukraine in 1932–1933. Thereafter, even if the term “genocide” was established much later, the Holodomor can be considered a genocide since it was a crime against humanity.

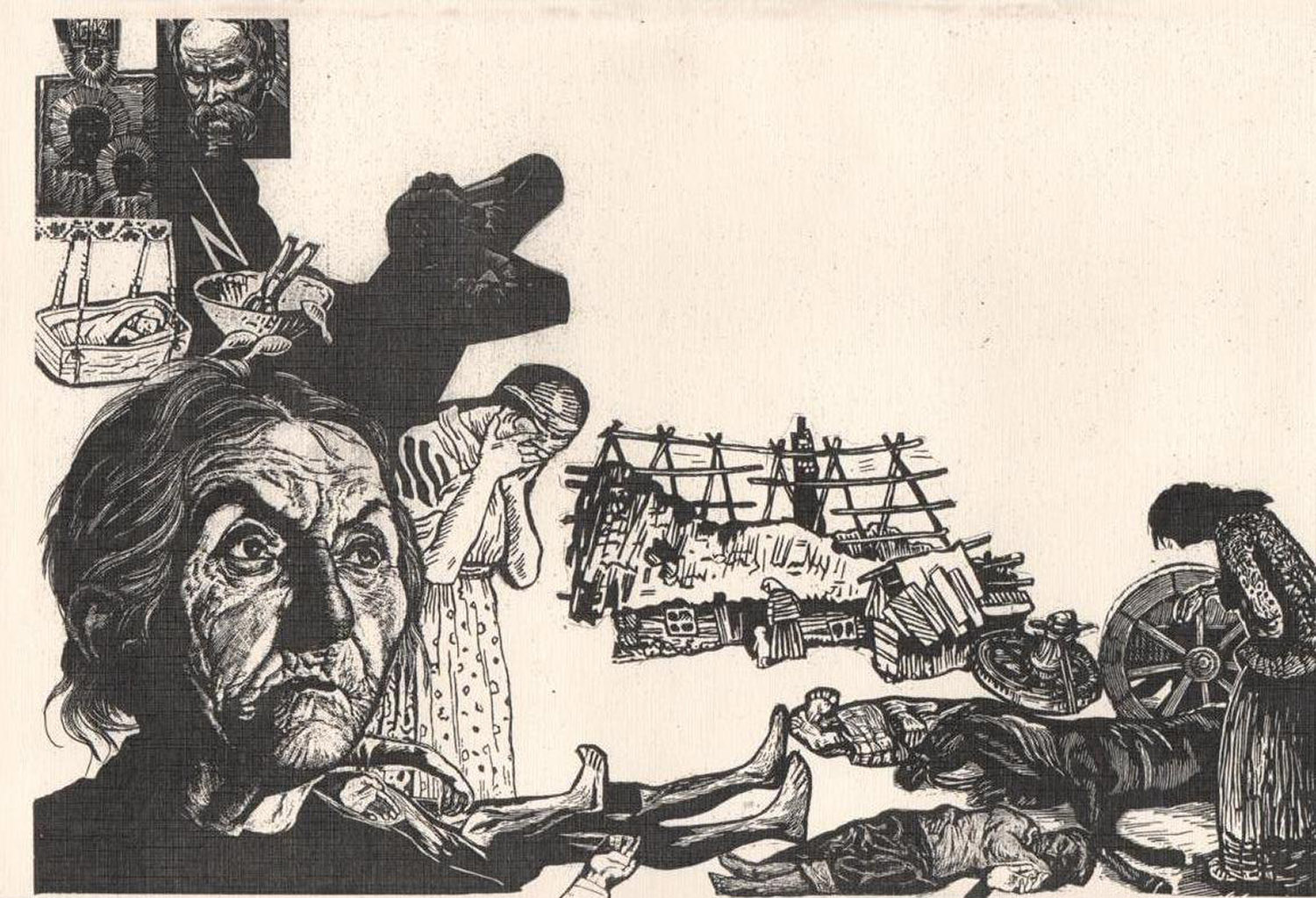

Графічна робота «Голод - 33». Автор – член Національної спілки художників України Микола Гнатченко (м. Харків).

The silent genocide

The civilian losses in Ukraine during World War II are equal to the losses during a few peace-time months in 1933.

When it comes to genocide on a global scale, most people think of the Holocaust. It became the measure of absolute evil, and it is considered such even by people who were completely untouched by the tragedy. According to Jeffrey C. Alexander, the Holocaust phenomenon is hidden in its publicity. Using mass media, the Jews were able to speak about their trauma right after the military freed the concentration camps. Moreover, the constant mention of the topic in the media with the emphasis on the Jewish victims as a separate group out of all military casualties made the Holocaust so widely known.

In contrast, the Holodomor happened in a closed-off country. A country where all of the invited foreign reporters and diplomats were taken on special “tours”. Such tours included blooming towns and villages, where local people were satisfied and happy because the great Communist Party took them under its wing. As a bonus, there were meetings with Stalin himself or someone in his circle, as with George Bernard Shaw. The USSR used modern opinion leaders of the Western world and basically monopolised the dialogue by distorting it to its advantage.

“Experience consists of stories that are extremely personal, extremely sensitive. The stories are such that they help to establish identity. It can be done with the use of psychological tools, but media can also be used in the same way” (Viktoriia Horbunova, a psychologist).

slideshow

The Holocaust became integrated into the life experience of people who were far away from it, through stories of the deceased and the victims. The Holodomor victims could not speak, not even in their own families. It was partially due to psychological changes, PTSD, and the unwillingness to rekindle the terrible memories; and partially due to the political repressions that reached their peak in the 1930s, deporting thousands of dissidents to the far east of the USSR. The famine changed their mentality, values, and way of life. Read more about this in our article “How does the Holodomor influence Ukraine today?”

In 1948, the UN adopted The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. “Genocide” as a term was coined by Raphael Lemkin, and the Convention itself came to be a reaction to the Holocaust. It established genocide as acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group.

Raphael Lemkin undisputedly called the crime of the Soviet government against Ukrainians a genocide:

— This is not simply a case of mass murder. It is a case of genocide, of destruction, not of individuals only, but of a culture and a nation.

The first country in the world to recognise the Holodomor as genocide was Estonia. On 20 October 1993, the Parliament of Estonia made a statement, condemning the Soviet politics of genocide, and showed solidarity in remembering the 1932–1933 Holodomor victims. As of today, 17 countries recognise the Holodomor as genocide: Ukraine, Australia, Canada, Hungary, Estonia, Vatican City, Poland, Lithuania, Georgia, Peru, Paraguay, Ecuador, Columbia, Mexica, Latvia, Portugal, and the USA.

Графічна робота «Голод - 33». Автор – член Національної спілки художників України Микола Гнатченко (м. Харків).

On 28 November 2006, the Supreme Council of Ukraine passed a law “On the Holodomor of 1932–1933 in Ukraine”, according to which the Holodomor was recognised as genocide of the Ukrainian people. For Ukrainians, it meant that the tragedy of thousands of families finally came out. The stories about the terrible events of 1933 that were passed in absolute secret were finally heard.

Russia, as the successor to the USSR, admits the fact of the famine, but completely refuses to recognise the Holodomor as genocide against the Ukrainian people. It would, obviously, destroy the notion of “brotherly nations”. The USSR’s position did not allow acknowledging the millions of victims, in the same way as Russia’s position now does not allow admitting annexation of Crimea and the undeniable occupation of parts of Donbas.

Journalists became tools that were used by the communist totalitarian regime for the suppression of awareness about the Holodomor and its refutation in the eyes of the Western general public. Today, mass media can become a tool that allows silent victims to finally speak up and share their stories. The experience of the Holodomor shows that media and publicity can be a powerful tool for debunking myths and spreading awareness about the Holodomor as a genocide of Ukrainian people.

“We did not have mass media then. There needs to be a tool to share. It is happening now, and it is a very natural process. There is nothing to be afraid of, this experience needs to happen” (Viktoriia Horbunova, a psychologist).

Walter Duranty, who once praised Stalin and called thousands of deaths the necessary running cost, still holds the Pulitzer Prize, although his name does not inspire ovation now but instead stands next to the Soviet regime’s crimes. The books and movies about Gareth Jones are bestsellers, and in spite of everything, he himself became a symbol of honest journalism and truth.

supported by

The material was published in cooperation with the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide with the support of the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation.