In this episode, the Decolonisation series hosts Uilleam Blacker, a renowned scholar of Ukrainian literature and one of the most prominent contemporary translators of Ukrainian literary works into English. In the interview, Dr Blacker reveals how colonial influences have shaped Ukrainian literature over time, what obstacles hinder its international popularity, and why the anti-colonial themes developed by Ukrainian authors can resonate globally.

When I began exploring your work, I was struck by your profound knowledge of Ukrainian literature and culture. Could you share your background and tell whether studying Ukrainian was challenging given the limited availability of studies and translations?

It’s quite unusual for someone in the UK to start studying Ukrainian culture, literature, or the language, as there are no established academic pathways leading to a specialisation in Ukraine. My interest in Ukraine began during my university studies in Glasgow, where I was studying Russian and Scottish literature. As someone from Scotland, I’ve always been interested in my own culture and literature. Over time, I realised there were other cultures somewhat like mine, although in very different contexts. These were “smaller” nations or cultures situated on the edges of “larger” ones, shaped by complex and often challenging relationships with their powerful neighbours — relationships that gave rise to intricate and very interesting cultural interactions. So, I was naturally drawn to look for what the Ukrainians were writing, as well as Belarusian, Georgian, or Kazakh writers. It took a lot of work to find their books; there was not very much material – definitely nothing in English. It was mainly through independent study, talking to Ukrainians, travelling to Ukraine, and starting to learn the language on my own that allowed me to do this. I was also quite lucky — after graduating, I moved to Poland and studied at the Jagiellonian University (the second-largest university in Poland, located in Kraków – ed.) for a year. There, I discovered that the local perspective on East Central Europe was very different. There were quite extensive Ukrainian studies at the Jagiellonian University. They had resources to study Ukraine, and it was also around the time of the Orange Revolution. I was living in Poland at the time, so there was a lot of attention on Ukraine. I was able to find a wealth of information about Ukraine through Poland during my initial period of interest. However, for an average student living in the UK, learning about Ukraine was much more complicated.

The Orange Revolution

was a series of nationwide protests against electoral fraud favouring the Russian-backed candidate Viktor Yanukovych in Ukraine's 2004 elections. The rallies led to a re-run, resulting in the victory of pro-EU Viktor Yushchenko and broad democratic reforms.You mentioned in one of your interviews that your interest in Ukrainian literature began, in many ways, with Mykola Hohol, who is often regarded as the Russian author Nikolai Gogol. Could you share more about how your journey started and why you chose to focus on Ukraine?

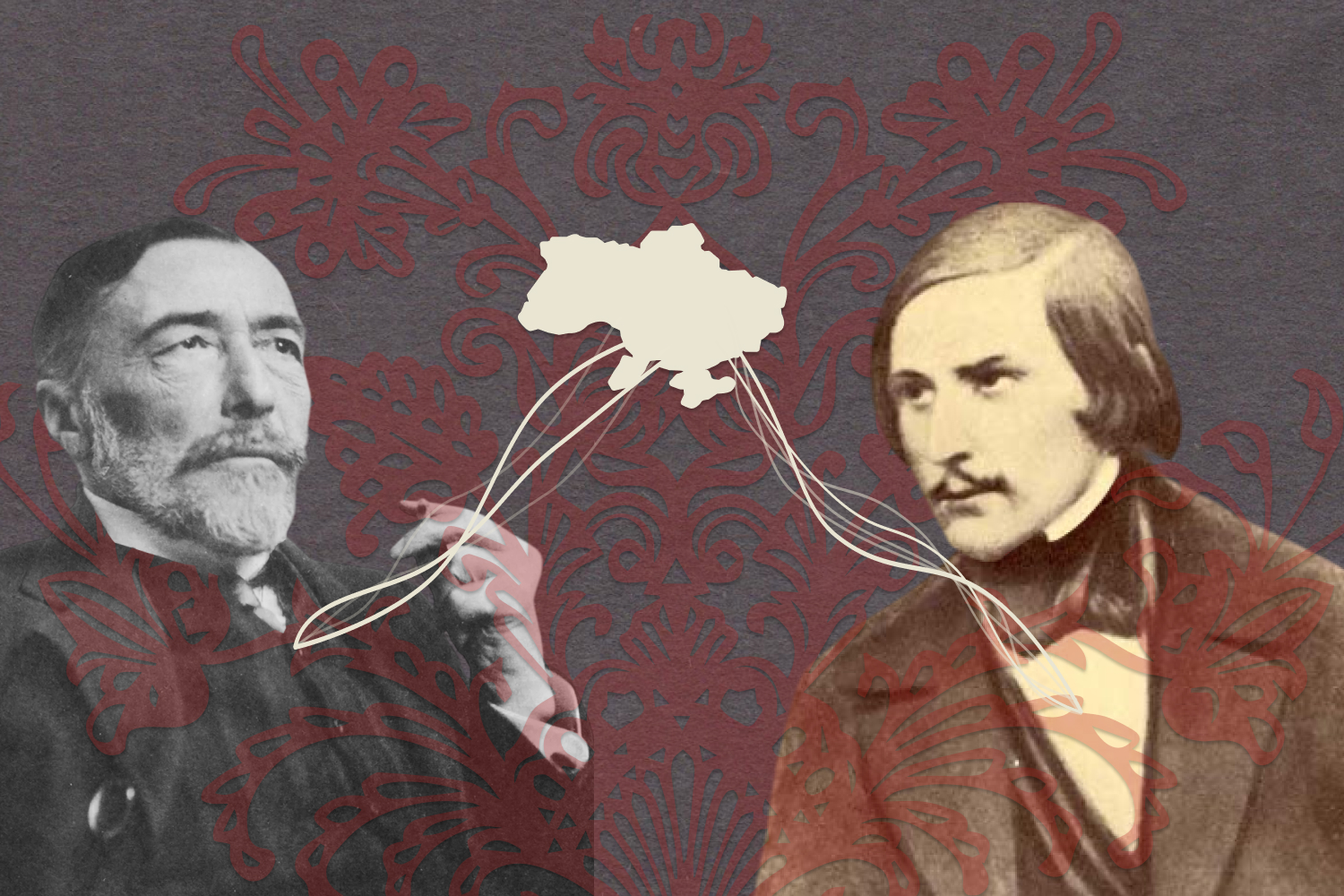

I first encountered Ukrainian literature through Hohol, although I didn’t initially realise it was Ukrainian literature. I was about 16 or 17 years old and came across a book titled Diary of a Madman (Hohol’s satirical story following a low-ranking civil servant who slowly descends into madness, believing he is the King of Spain – ed.). I was completely blown away by the writing — it was strange, funny, eccentric, and unlike anything I had read before. It presented such a unique way of looking at the world, and I was curious to learn more about the writer and his culture. I still have that copy, but if you look at the cover and introduction, there’s no mention of Hohol being Ukrainian. He’s simply described as a Russian writer. By chance, I soon learned there was another side to him. I come from a small island in the northwest of Scotland, and there happened to be a Ukrainian man living there — very unusual at the time. I got to know him, and he gave me a copy of Hohol’s Dykanka stories (Hohol’s early collection of short tales, based on Ukrainian folklore, regarded as one of the founding works of Russian classical prose – ed.). That’s when I realised Hohol was not just a Russian writer but also profoundly connected to Ukrainian culture. He seemed to exist between two worlds, straddling Ukrainian and Russian identities, which I immediately found fascinating. It was intriguing how a writer could be two things at once and have this kind of double identity. Hohol’s works can be read on different levels. On the surface, there’s the humour, the exoticism, and the vibrant portrayal of Ukraine. But beneath that, there’s a subtle layer of subversiveness, and many have argued that Hohol’s work hints at a critical attitude towards the empire. I believe that subversiveness is there, and it’s something I never tire of exploring in his texts.

Mykola Hohol

was a Ukrainian-born writer, known for his phantasmagorical and satirical works critiquing Russian imperial society and widely regarded as one of the most important figures in Russian literature. Although he wrote in Russian, his Ukrainian background had a profound impact on his legacy.

Daguerreotype of Mykola Hohol taken in 1845 by Sergei Lvovich Levitsky (1819–1898).

In one of your previous interviews, you’ve made an insightful comparison between Hohol and Kafka — a Czech Jew writing in German who achieved greater recognition than many of his Czech-speaking contemporaries. Both Hohol, who wrote in Russian, and Kafka, who wrote in German — the languages of their respective empires — were able to gain proximity to the canon of international literature through these imperial languages.

I’m not the first person to note similarities between Hohol and Kafka (a Czech-born modernist writer known for his surreal stories exploring themes of alienation, bureaucracy, and existential anxiety – ed.). And they’re not the only writers who demonstrate that there is no simple connection between the writer’s cultural background, the language they write in, and the political state which might be tied to that language or not. We tend to imagine the world as divided, which is a distinctly European, even Eurocentric, perspective. We see the world as split into political states with borders, each linked to a particular nationality, culture, and language. This is how we project political realities onto culture and literature. However, the reality is far more complicated and much more interesting than that. You rarely get a culture or literature confined to political borders or a language only contained within political boundaries. In the middle of the 20th century, people moved from one place to another because states wanted the world to be divided more simply. They want one type of person to live in one kind of state so that they will be easier to rule. However, looking at the development of literature, we find many writers who challenge this simplistic view, reflecting the complex overlap of politics, culture, and language. Hohol is one of these writers, as is Kafka. In fact, many of these writers emerge from the edges of empires, which is why Ukraine is particularly rich in those types of writers.

We can look at Ukrainian and non-Ukrainian writers from Ukraine who wrote in two, three, or even four languages — writers who belong to multiple cultural traditions and could move their work between different languages. This is one of the most fascinating aspects of Ukraine, though it can be hard to explain to anglophone audiences. In the UK and the US, bilingualism is less common, and we’re not used to the idea that someone can exist in more than one language and culture, shifting between them. The ability to create something that isn’t tied to a single national identity is more familiar in places like Ukraine, where such fluidity is more easily seen.

Another great example of this is Joseph Conrad, a Polish writer presumably born in Berdychiv (a city in central Ukraine – ed.) — or at least definitely in Ukraine. Ukrainian writers once identified three leading influences in Conrad’s work: the Ukrainian land, the power of the Polish spirit, and the greatness of the English language. Given that Conrad is a canonical yet distinctly British writer, how do you think we should approach authors like him, who embody multiple identities?

Conrad is a great example of a writer whose background makes it hard to define which literature he truly belongs to. Of course, he writes in English, but, as you mentioned, his roots lie in Ukraine, in a Polish background, and in a world shaped by the conflict between Poland and the Russian Empire. He also travelled widely across the globe. Conrad is one of those writers who seems to belong to many different contexts, yet at the same time, to none. This is what makes writers who write in “big languages” — German, English, Russian — yet come from peripheral or multicultural backgrounds so intriguing and valuable.

Kafka, for example, is a Czech Jew living in Prague, writing in German; Hohol is a Ukrainian from Ukraine writing about Ukraine, but in Russian. Even though Hohol uses Russian, his language is distinctly his own — it’s not classical Russian, not the same Russian as Pushkin’s. His Russian is influenced by and infused with Ukrainian. It’s Russian that challenges Russian readers, presenting them with a sense of otherness and cultural distance. How did Hohol become famous? He did so by writing about Ukraine. Look at the opening pages of his works. A narrator from Ukraine is explaining to Russian readers what Ukraine is. The conclusion here is clear: Russian readers don’t know what Ukraine is, and they need someone to explain it to them. So, when we think of Hohol as a Russian writer, we have to ask why, from the very beginning of his career, he’s defining his literary path through the differences between his own context and the Russian metropole — and doing so in Russian. There’s something complex and provocative about entering an imperial culture and language, taking ownership of it, and yet subverting it. Through this, these writers assert their distinctiveness, offering a different perspective in a subtle and often mischievous way.

We can look at Conrad, who’s most famous for the Heart of Darkness, as a European writer who writes about the dark side of European colonialism in Africa. However, this writer came from another type of colonial experience. He came out of Ukraine, an arena of competition and conflict between different empires or imperial-like states for hundreds of years: the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Russian Empire, and the Ottoman Empire. We could also speak about the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as a quasi-empire. So if you understand Conrad and his origins, and the fact that he comes from a Polish background, which has suffered from Russian colonialism (Russia played a key role in partitioning the Commonwealth – ed.), you can understand why he’s coming into this other – imperial – colonial context. You can see a kind of logic that is not consistently recognised. I think the whole dimension of Conrad’s origins in Ukraine is often overlooked, but it’s something that can reveal a lot about his most famous works.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

was a Polish-led monarchy in Central and Eastern Europe, encompassing the territories of present-day Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine, Belarus, Latvia, and Estonia from the 16th to the late 18th century, when it was divided between Russia, Prussia, and Austria.It’s also fascinating that his father was sent to Siberia because he resisted the Russian Empire, and Conrad grew up in a state of immigration. This highlights something about the cultural diaspora of countries like Ukraine and Poland, which I think is unknown. Could you talk about the diaspora’s contributions to the literary legacy of Ukraine, Poland, and maybe the region?

It’s a complicated question. It depends on how we define diaspora. But it’s undoubtedly something intimately connected to histories of imperialism and the creation and disintegration of empires. This then causes an empire to fall apart and leave a specific group that exists within one state in different states. Or empires can force people to leave the empire. If you think about the Jewish diaspora in North America and other places, many of them got to where they ended up because of the antisemitism and pogroms in the Russian Empire. The same goes for the Ukrainians moved there for reasons that partly could be related to repression, cultural repression, linguistic repression, and so on, but also partly to economic factors (nearly 2 million Ukrainians migrated to the West from the late 19th century to the 1930s – ed.). Whether cultural or economic, we can trace these things back to empires. The 20th century is often defined by diaspora, a significant characteristic of the era. Ukraine is a powerful example of a state deeply affected by the shifting borders caused by imperial competition and the displacement of people due to the wars that follow. We see this continuing today, with many Ukrainians displaced by Russia’s ongoing invasion. Diasporas don’t simply vanish when they settle in new countries; they tend to self-organise and often look back to their homeland. The Ukrainian diaspora is a compelling example of a community that has preserved and cultivated its identity, developing its own culture and even language, which, in many ways, has evolved separately from what is happening in Ukraine. This highlights the complexity and richness of Ukrainian culture and identity, with multiple versions of it existing across the world. In the late 19th century, Ukrainian literature took one form in the Russian Empire, another in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and by the 20th century, a distinct version emerged within the diaspora. These versions are not isolated; they are interconnected and influence one another, yet borders and other factors have caused them to develop in different ways. As a result, you have to study Ukrainian literature not only as the development of a single literary tradition but also as one with distinct pathways and branches growing within it.

You mentioned Ukraine being, in a way, a playground for different empires — the Russian Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. What would you say about the state of the Ukrainian language and literature under these different empires?

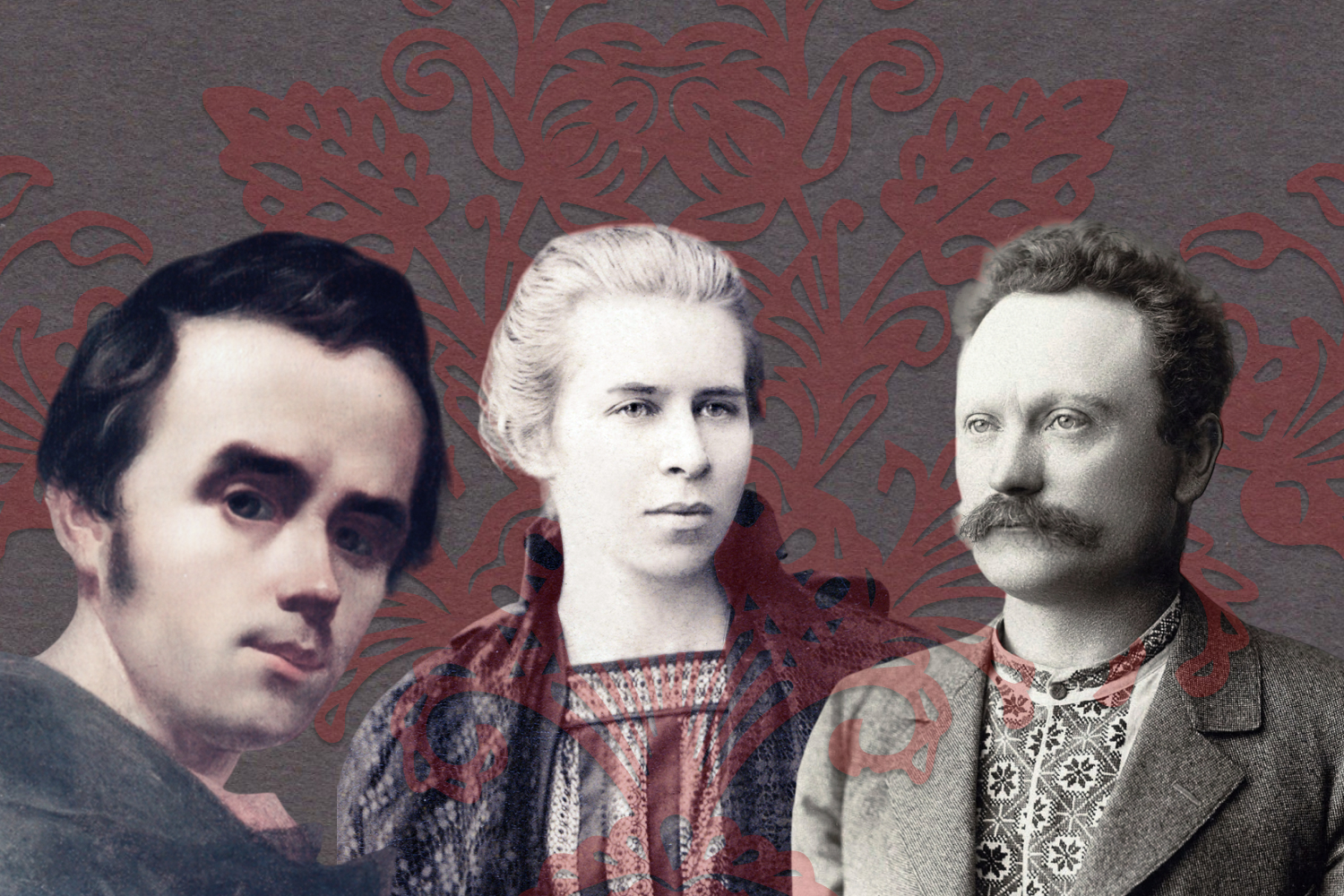

Ukrainian writers were writing in different historical and political conditions. The standard language was different, so if you read texts by Franko, he’s writing in another kind of Ukrainian than his contemporaries in the Russian Empire (Ukrainian lands were split between the Russian and Austrian empires in the late 18th century and reunified under Soviet occupation after WWII – ed.). The processes of the standardisation of the Ukrainian language was still developing and quite fluid well into the 20th century. Bilingualism or multilingualism varies depending on the context. Ivan Franko, one of the top three canonical Ukrainian writers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, is a prime example. He wrote across various genres and paradigms, but he is best known as a realist prose writer who addressed themes of Ukrainian nationhood, the working class, and the peasants. He was deeply concerned with both national and socio-economic rights. However, a significant portion of his output was written in Polish, as he contributed to Polish newspapers and engaged with Polish culture. He also wrote about Polish-Ukrainian relations and explored other cultural contexts around him. He understood Yiddish, translated from it, and had an interest in Jewish culture and Ukrainian-Jewish relations.

Ivan Franko (1856–1916)

was a Ukrainian writer who lived under the Austro-Hungarian Empire and is considered one of the most important figures in Ukrainian literature. As one of Ukraine's most prolific writers, he was also a leading early 20th-century political thinker, advocating for socialism, democratic reforms, and the creation of an independent Ukrainian state.

Portrait of Ivan Franko. Kosiv, 1897. Author: Ivan Trush.

On the other side, in the Russian Empire, writers often wrote in both Ukrainian and Russian, engaging with Russian culture and participating in polemics with it. You can look at one Ukrainian writer, for example, who creates a distinct Ukrainian literature while interacting with Polish and German influences. Meanwhile, their counterpart in the Russian Empire is doing something similar, but in dialogue with Russian culture. This contrast highlights two different versions of how literature can develop under different imperial conditions. And, of course, it was easier for Franko than for his contemporaries in the Russian Empire. So, we have someone like Lesia Ukrainka, for example — the great dramatist and feminist — who corresponded frequently with Franko and collaborated with him in various ways. She worked in the Russian Empire but faced significant challenges, unable to have her plays staged, struggling against censorship, and fighting the repression of Ukrainian identity and culture. Lesia Ukrainka came from a prominent Ukrainian intelligentsia family, where nearly everyone, especially the women, was arrested at some point. These were strong activists and writers who suffered repression simply for wanting to write in Ukrainian, discuss the distinctiveness of Ukrainian culture, and highlight the imperial oppression of that culture. Naturally, the Empire sought to silence them. At the same time, someone like Franko operated in a more accessible environment when it came to language and culture. While Franko was also arrested, it was for his socialist beliefs, not for the same reasons as Ukrainka (she was briefly detained in 1907 for advocating Ukrainian language and culture, which the Russian Empire aggressively suppressed – ed.).

Lesia Ukrainka (1871–1913)

was a Ukrainian poet, playwright, and feminist, considered one of Ukraine's greatest literary figures. She is known for her extensive legacy that explores themes of national identity, personal freedom, and women’s rights, often using symbolism and modernist techniques.The three key figures of Ukrainian literature — Taras Shevchenko, Ivan Franko, and Lesia Ukrainka — are especially significant because Ukraine’s lack of statehood meant cultural figures often became the voices of the nation, making their impact go far beyond literature. Could you highlight some of the specific literary techniques or approaches they used?

When we read Shevchenko, we might have the impression we’re reading a writer who’s very much grounded in his specific context. We don’t feel this cosmopolitanism when we read, especially Lesia Ukrainka, who’s all about this cosmopolitan outlook. Paradoxically, this was very European for the time. It was the era of romanticism and romantic nationalism, where nothing was more European than being deeply rooted in your cultural tradition. This idea originated in Germany, influenced by German philosophy and concepts of folk and national culture. It spread very quickly around Europe, so romantic writers were exploring their distinctive traditions in Europe at the time. And it’s important to remember that we’re talking about the early 19th century. The idea that we can write sophisticated, complex literature in vernacular languages — languages of everyday speech — seemed relatively new in some cases. This led to a focus on the native language, local traditions, and the concept of the nation. At the time, it was a novel idea to organise both culturally and politically around a nation with its own culture and language. This was very European, and in many ways, Shevchenko was very European too. One of my favourite moments in Shevchenko’s writing is an unpublished introduction to one of the editions of Kobzar (an 1840 collection of Shevchenko’s poems, regarded as the pinnacle of both his legacy and Ukrainian classical literature – ed.), where he mentions Scotland — I find it particularly interesting. He also talks about the difference between Walter Scott and Robert Burns.

Taras Shevchenko (1814–1861)

was a Ukrainian poet and artist, widely regarded as the founder of modern Ukrainian literature. His works, focused on themes of freedom, social justice, and Ukrainian identity, played a key role in shaping the Ukrainian liberation movement throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.I wanted to ask you if Shevchenko reminds you of Walter Scott in terms of their significance to their nations — not their literary styles, but the impact of their legacies.

Shevchenko saw Burns as the model to follow because he wrote in his own language about his own people, while he argued that Walter Scott didn’t truly understand his people. Scott wrote in English for a wider British audience. So, the parallel would be that Hohol is like Scott, and Shevchenko is like Burns. Scott, like Hohol, was fascinated by the historical tension and conflict between England and Scotland, but he depicted that history moving toward a harmonious union. Scott wasn’t a Scottish nationalist; he supported the union and was quite conservative politically, much like Hohol, even though there are elements in Hohol’s work that subvert the empire. I think if you read some of the stories, they’re about negotiating a synthesis and harmony between different cultures within an imperial context, something many writers at the time saw as both possible and desirable. In contrast, with Shevchenko, we see an anti-imperialism that feels very ahead of its time. The way he very firmly calls out cultural imperialism, the use of religion in imperial conquest, and the use of the civilising mission (a colonial narrative framing the imposition of imperial culture and institutions as beneficial to the subjugated societies portrayed as backward – ed.).

Shevchenko wrote not only about Ukraine but also about the Caucasus. In this famous poem, he explicitly criticises the idea of the imperial “civilising” mission. This was in the 1840s, which is quite remarkable. I think he also understood that Robert Burns was a great example of a writer who didn’t write in standard English, the language of the imperial centre, but used his native linguistic tradition to create high literature. And that’s what Shevchenko wanted to do: he was interested in the idea of taking this “marginal language” and creating something else — important literature that would be crucially understandable to ordinary people, not just a small elite.

"Caucasus"

Shevchenko's 1845 poem, strikingly condemning the ongoing Russian conquest of the Caucasus. Empathising with oppressed Caucasian peoples, the poem became one of the earliest and most politically charged anti-colonial works created within the Russian empire.

This explains a memory from my childhood — why the Soviet Union seemed to have such an affection for Walter Scott. It’s interesting because his books were always just there, you know? In every home, you could find at least a few of his works in Russian.

Without Walter Scott, it would have been hard to imagine that there would be Hohol. People often forget that Hohol’s most famous work during his lifetime was not Dead Souls (a satirical novel about a man buying deceased serfs to acquire their property – ed.) but Taras Bulba, that sold the most copies. It was a historical adventure novel, entirely based on the model of Walter Scott. How can we take history and reimagine it as the basis for the modern novel, using it to tell a story that connects readers through their shared experience of the narrative? Scott pioneered the idea that people could learn their history through the novel, and Hohol did the same. This is also an interesting moment for both Ukrainian and Russian Hohol. He wrote two versions of the same novel. The first, written in Ukrainian, focuses on Kozak history and the fight against the Poles, without mentioning Russia. Later, in the 1840s, Hohol sought to align more closely with the Empire, concerned that some of his earlier works were too critical of imperial society. At that time, the Russian Empire was pushing for writers to focus on Russian history. So, Hohol decided, “Okay, I’ll take that Kozak history novel from 1835 and rework it”. He then starts adding all these different lines into the same novel about the Russian Tsar and Orthodoxy, the ancient Russian lands, and all of this stuff that feels entirely artificial when you read it. You can see this shift from Hohol saying, “I’m a writer with a vision of history rooted in where I come from — the imperial periphery, a place the readers in the centre know little about. I want to show them the difference and tell a story about us in Ukraine that’s not the same as you in Russia,” to saying, “Okay, I’ll add a few paragraphs here and there, and suddenly, we have a historical novel suggesting that where I come from was always Russia.”

Kozaks

were a warrior class and democratic military state that emerged in the 15th century in the territories of modern-day Ukraine, primarily for frontier defence. The Kozaks played a pivotal role in shaping Ukrainian statehood and national identity.You mentioned numerous limitations placed on writers in the Russian Empire, including the ban on using Ukrainian language in their work. While discussing the oppression of Ukrainian writers, I’d like to bring up the continuation of the Russian Empire in the form of the USSR. In this context, we must also address the phenomenon of the Executed Renaissance, which is crucial to understanding Ukrainian literature. Could you tell us more about its significance?

The Executed Renaissance

was the generation of Ukrainian artists, writers, and intellectuals, active mostly in the 1920s, who were repressed under Stalin's rule as part of the broader Soviet campaign against Ukraine’s national identity and political autonomy.

Photo: Mike Johansen. Selected works Ed. R. Melnikov. 2nd edition, supplemented. Kyiv. Smoloskyp. 2009, 768 с. Series “Executed Renaissance”.

By the Executed Renaissance we mean the execution of writers under Stalin. Obviously, the argument that you often hear is that Russians were also murdered in the purges, which, of course, is true. But that perspective is very Russo-centric because what you miss is that writers were not being executed just for writing in Russian – such an idea didn’t even exist. The fact that you wrote in the Russian language and of itself was not a political statement, and it didn’t put you in danger. All official Soviet literature of socialist realism (the officially mandated artistic style in the USSR from 1934 to 1980, promoting the ideals of the Communist Party – ed.) was written in Russian, and writers across the Union were encouraged to adopt the language. That’s often forgotten by people who look at the Stalinist purges from the Russian point of view. Of course, Stalinist repressions were different to Tsarist repressions; there are different ideological underpinnings to them. But we also see a through line, a continuation of that centre-periphery dynamic, whereby we have a large state centred around Moscow, with Russian culture and language at its core. The authorities, whether under Stalin or the Tsars, saw it as essential to impose the centre’s culture and language on the periphery to prevent the state from falling apart. This is a thread that runs through Russian history, from the earliest Russian Empire to Putin’s Russia today.

The local and national languages and cultures on the edges of the Empire were seen as threats to its unity, potentially leading to disintegration. This creates a continuity between the repression of writers in the 1930s and earlier persecutions under the Tsars. The language used to describe separatism is strikingly similar across both periods. In the 1930s, writers were often labeled as nationalist terrorists or fascists — terms that echo the rhetoric we hear from the Kremlin today. The promotion of the Ukrainian language was seen not as cultural figures standing up for the linguistic and cultural rights of millions of people but as some kind of subversive and separatist plot that was probably inspired from outside by external enemies. This is something that you find going back to the Russian Empire, where they’re convinced that somehow it’s the Poles who are manipulating the Ukrainians into thinking that they’re different from the Russians. Even very similar ideas come down to today when we get the idea that it’s all the EU convincing Ukrainians that they want to move away from Russia.

In 2022 and 2023, we saw a resurgence of talk about the Executed Renaissance as Russian occupying forces began arresting and murdering writers once again, in much the same way. For instance, Victoria Amelina was a well-known Ukrainian novelist and war crimes investigator. She was among those who uncovered the diary of writer Volodymyr Vakulenko, who was murdered in the occupied territories. Vakulenko had kept a secret diary of life under occupation and buried it in the ground. Amelina looked at his case and warned of the danger of a new Executed Renaissance — a new purge of Ukrainian writers by Russia if they gained control of them. Tragically, she was killed in a missile strike in the east of Ukraine, where she had been frequently traveling to speak with people, gather testimonies, and document Russia’s war crimes. She became a victim of that very danger she had warned about months before. We need to understand this broader context, especially in the context of what the term Executed Renaissance means. It was Polish intellectual Jerzy Giedroyc (a renowned Polish post-WW2 intellectual who played a key role in advocating for Polish-Ukrainian cooperation and the democratisation of Eastern Europe – ed.), the prominent émigré in Paris, who coined this term for an anthology of Ukrainian writers killed by Stalin. These writers, who had lived within Soviet Ukraine, supported some form of socialism or communism but believed in an independent Ukrainian socialist republic, free from Russian control. Writers of the 1920s, in particular, spoke forcefully about how Russian imperialism continued under the Bolsheviks, with policies that eroded Ukraine’s political and cultural autonomy, mirroring those of the Tsars. Writers like Mykola Khvyliovyi, whose work is highly relevant to contemporary discussions on decolonisation, wrote about the need for Ukraine to shed the negative effects of centuries of Russian imperial rule and move towards Europe, embracing a global culture that believes in itself. They rejected being forced into a cultural hierarchy where Russian culture was dominant, and Ukrainian culture was expected to imitate it. This generation of writers was cosmopolitan, forward-looking, and eager to modernise Ukrainian culture. Their modernist, avant-garde ideas terrified the centre, as they saw this emerging culture as too modern, too confident, and too self-sufficient. By the 1930s, Stalin found this unbearable, leading to an extremely violent response in which hundreds of these writers were murdered, effectively wiping out a whole generation of Ukrainian writers. Of course, the most tragic aspect is the loss of those lives, but the impact goes beyond that. A whole period of Ukrainian literature became invisible, both to Ukrainians and to the world. When we think of avant-garde modernist literature in Europe, certain writers, like Kafka, come to mind. Russian writers might also be familiar to the average European reader, but they likely wouldn’t be able to name a Ukrainian avant-garde writer. Why not? It’s not because such writers didn’t exist — they did. However, they’ve been made invisible because of that initial act of violence.

Mykola Khvyliovyi (1893-1933)

was a leading figure of the Executed Renaissance generation. Initially a committed Ukrainian communist, he soon became disillusioned with the USSR, advocating for Ukrainian cultural autonomy and severing ties with Russian culture in favour of European tradition. Khvyliovyi’s suicide in 1933 foreshadowed mass Stalinist reprisals against his generation’s writers.Since the start of the full-scale war, we’ve been talking more about the Executed Renaissance in Ukraine as we see certain patterns repeating. This year, much of the focus has been on Sandarmokh, part of the Gulag system, where over a thousand people were executed in 1937 as part of the Executed Renaissance. Many of those killed were Ukrainian writers, scientists, and artists. One such name is Valerian Pidmohylnyi, who was murdered there at just 36. I’ve recently heard a Ukrainian scholar suggest that if he had survived, he might have become Ukraine’s Nobel laureate in literature.

The Sandarmokh tract

is a woodland area in northern Russia where Soviet secret police executed over 9,000 political prisoners in the 1930s, nearly a third of whom were part of Ukraine's cultural and scientific elite.

Whether Pidmohylnyi or another writer would have won the Nobel Prize is an interesting question. It highlights the impact of imperial violence, not just in terms of censoring what was written, but also in preventing so much from being written at all. Many books were never completed, or never written, and a whole generation of writers was lost, killed in their 30s and 40s — an age when writers are often at their best. This situation mirrors that of Hohol and Shevchenko: Hohol received support from the Tsar to write, while Shevchenko did not. In both the Tsarist and Soviet systems, if you wanted access to resources, time, and support to write and publish, you had to align with imperial culture. Ukrainian writers were often denied that space, time, and resources, making it incredibly difficult for them to pursue a career as professional writers. Unlike Russian writers like Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, who had the time and resources to write long novels and see them published and serialised, Ukrainian writers lacked those opportunities. This disparity influenced what was written and what wasn’t. If writers like Shevchenko had not been arrested and exiled, but instead allowed to develop as poets and prose writers, we might have seen incredible novels from him. Though he did experiment with prose and the novel, he lacked the time, resources, and freedom to fully pursue it, as the empire took that from him.

Pidmohylnyi was an extremely talented writer, deeply interested in Ukraine, but he was also a translator of French literature, which was how he sometimes made a living. He knew French literature well, and you can see its influence in his work. He’s most famous for his novel The City, which tells the story of a young man who comes to Kyiv in the early days of the Soviet state with a cultural and class mission. It’s a brilliant urban novel, and if anyone familiar with Kyiv reads it, they will feel the specifics of the city and fall in love with it through the novel. So, who knows — would he have won the Nobel Prize? Why not? He was murdered as a young writer, and like many of his generation, we’ll never read the works he would have written. This pattern repeats again and again.

When talking about the Nobel Prize, Ivan Bahrianyi often comes up — though, unfortunately, he died before he could be nominated. For me, his story is a striking example of Russia’s imperial influence even beyond its borders. Ivan Bahrianyi, for those who may not know, was imprisoned and sent to the Gulag several times. He managed to escape and, during the Nazi occupation, fled to Europe. Twenty years before Solzhenitsyn, he told the story of the Gulag, yet while the world remembers Solzhenitsyn, Bahrianyi is largely forgotten outside of Ukraine.

Ivan Bahrianyi (1906-1963)

was a Ukrainian writer and political activist, renowned for his works addressing resistance to the Soviet Great Terror. Repeatedly persecuted by Soviet authorities, he escaped during World War II and joined Ukraine's independence movement in exile, becoming one of the first voices to expose Soviet atrocities in the West.

Ivan Bahrianyi, photo: UINP.

Again, this comes down to access to institutions, resources, and opportunities, with one of the key factors being translation. It’s difficult for a writer who hasn’t been translated into English to win the Nobel Prize. Typically, writers are first translated into English, which sparks broader interest in their work, leading to translations into other languages. This is a critical difference between Solzhenitsyn and Bahrianyi. Solzhenitsyn became this kind of co-celeb among Westerners, who were critical of the Soviet Union. Obviously, it was in the interest of the USA and the democratic Western world to give a platform to “Soviet dissidents”. In that context, they were particularly focused on Russian writers. It’s more complicated to support a writer from a lesser-known country who speaks about their specific problems. They wanted someone who could talk about the Gulag from a broader, more general perspective. Additionally, there is also a pre-existing interest in Russian literature, culture, and the “great Russian novels”. In the Western imagination, Solzhenitsyn is just another Russian writer who writes “big books” full of clever ideas, books that every educated person should read. It isn’t so much about the content of these books, but about the image of what an educated person should understand. Typically, these works come from writers who write in imperial or post-imperial languages, which are associated with “greater” cultural value. There’s not much logic to this, but it’s how we tend to think: the greater the state’s influence, the more valuable its culture is.

For that reason, someone like Solzhenitsyn is much more likely to be taken seriously and given credibility than someone like Bahrianyi, who comes from a context, culture, and language that we don’t know about. People are very resistant to things they don’t understand. This is precisely because of the history of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, which have ensured that the world doesn’t know what Ukraine is. Because, if the world truly understood what Ukraine is, it might start sympathising with Ukrainians and support their aspirations for independence. Russia has worked hard to make Ukraine invisible, but it’s not just about what Russia has done – it’s also about how the West approaches literature. We still tend to take seriously only writers from “big important literatures” — Russian, French, German, and so on. We find it difficult to engage with literature from places that seem unfamiliar or exotic.

These things also depend on how works are translated. You need translators, often not native speakers of the target language, who are interested in foreign cultures, willing to invest time, and knowledgeable enough to translate accurately. But to gain that knowledge, you need to study the language, often at university or school. If someone can’t learn Ukrainian, then no one can translate Bahrianyi into English. On the other hand, with Russian writers like Solzhenitsyn, there’s institutional support for Russian culture, which is widely regarded as an important “big culture”. This means there are many translators available. When these translators approach publishers, they’re met with the familiar names of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, and publishers are eager to promote works like Solzhenitsyn’s because they’re comfortable with the well-known Russian literary tradition. Publishers aren’t willing to take risks, as it ultimately comes down to making money, and readers are more likely to buy what they already know.

Many translations into English have happened thanks to the diaspora. The diaspora establishes its own publishing houses and university chairs in North America to get Ukrainian literature out there. However, it can’t influence the publishing policies of big publishers like Penguin, nor can it establish Ukrainian language programs in every university. While the diaspora can publish Bahrianyi through its own channels, the work stays within the community and lacks broader support from mainstream media, universities, and literary reviewers. These outlets are often biased toward Russian literature and reluctant to expand their horizons to include Ukraine, which they don’t fully understand. As a result, there are structural barriers in the West that make it difficult for a Ukrainian writer to gain visibility in English and be considered for prestigious awards like the Nobel Prize.

In your opinion, what needs to change, and who should drive these changes? Specifically, in terms of academia — how literature is taught — and how publishing houses operate. What further steps can be taken to raise the profile of Ukrainian literature on the global stage?

Some universities are starting to open new research centres, offer Ukrainian language courses, and rethink how they teach Russian history, culture, and its relationship to Ukraine. Many colleagues recognise the need for change, but others remain resistant. The term “decolonisation” can be understood in many ways, and for some, it feels threatening. For example, some may worry, at a basic level, that if Russian studies become too decolonised and Ukraine-focused, their jobs could be at risk. Changing the structures, syllabuses, and funding allocations in universities is a difficult process, especially when universities are driven by the commercial need to attract students. In the UK, education is largely market-driven, and if a course doesn’t attract enough students, it doesn’t pay for itself. Sadly, more students are willing to pay to study Russian than Ukrainian, and there is a wider crisis in language studies, as many are reluctant to learn foreign languages. However, change is possible if we reconsider how we approach the study of Ukraine. Ukraine is a fascinating country with a rich culture and language, and studying it can bring immense rewards. Beyond that, we can explore how Ukraine’s experience offers insight into universal themes, such as democracy and the history of empires — a timely and important subject today. One of the major mistakes is continuing with the structure of so-called Slavic studies, Russian studies, or East European studies, where the study of Russia is central and everything else — Poland, the former Yugoslavia, or Ukraine — is treated as peripheral, optional extras. This mindset needs to change. We should study Ukraine in relation to literature, empires, and modernism, drawing connections with places like India or South America. Ukrainian modernism should be studied as part of European modernism, not just Russian modernism. Ukrainian cinema should be considered in the context of European avant-garde cinema, not solely as part of Soviet cinema, which is often viewed as Russian. When it comes to languages and cultures offered at universities, Ukrainian should stand alongside French, German, Italian, and Spanish, not be treated as an optional, secondary-level language to study only alongside Russian.

In terms of broader publishing and getting literature out there, we should aim to position Ukrainian writers as part of a larger European or global conversation, rather than viewing them as provincial or parochial. Let’s discuss Lesya Ukrainka as a feminist who addresses global and universal concerns, positioning her as part of the European canon. She shouldn’t just be seen as a writer who tells us about the complexities and tragedies of Ukrainian history, which limits her potential audience. Similarly, let’s frame Olha Kobylianska as a feminist writer, someone who was exploring ideas that Virginia Woolf would engage with, but much earlier. This approach would allow us to present them to publishers in a more compelling way. I’m not suggesting we publish them simply because they’re Ukrainian and because Ukraine is at war, as that interest will not last forever.

Olha Kobylianska (1863-1942)

was one of Ukraine's most prominent female writers, one of the earliest feminist and social realist writers in Eastern Europe, exploring themes of social injustice, women's rights, and Ukrainian national revival.We also need to connect with people who are not naturally interested in Ukraine. This is a great opportunity to do so because of the war and the growing interest in Ukraine. Many journalists who didn’t know much about Ukraine before have come to the country, and they are essential allies. These individuals can communicate about Ukraine, not as specialists like me, but with the authority of someone who writes about culture and literature. Those of us who want to promote the study of Ukraine must engage with them, keep them on our side, and make use of their influence because they are valuable allies.