Russian propaganda, trying to justify aggression against Ukraine, relies on the thesis that Russians and Ukrainians are one nation, divided by the treacherous West. It tries to argue this using new disinformation about the oppression of the Russian language in Ukraine and old myths about Kyivan Rus as the “cradle of three brotherly peoples”. Russia is trying to completely appropriate the history of Rus by reviving claims about the need to “collect Rus lands” into one state. However, we have bad news for Putin: Ukraine is the true descendant of Rus, not Russia.

Geography. “Go to the Rus land, to Kyiv”

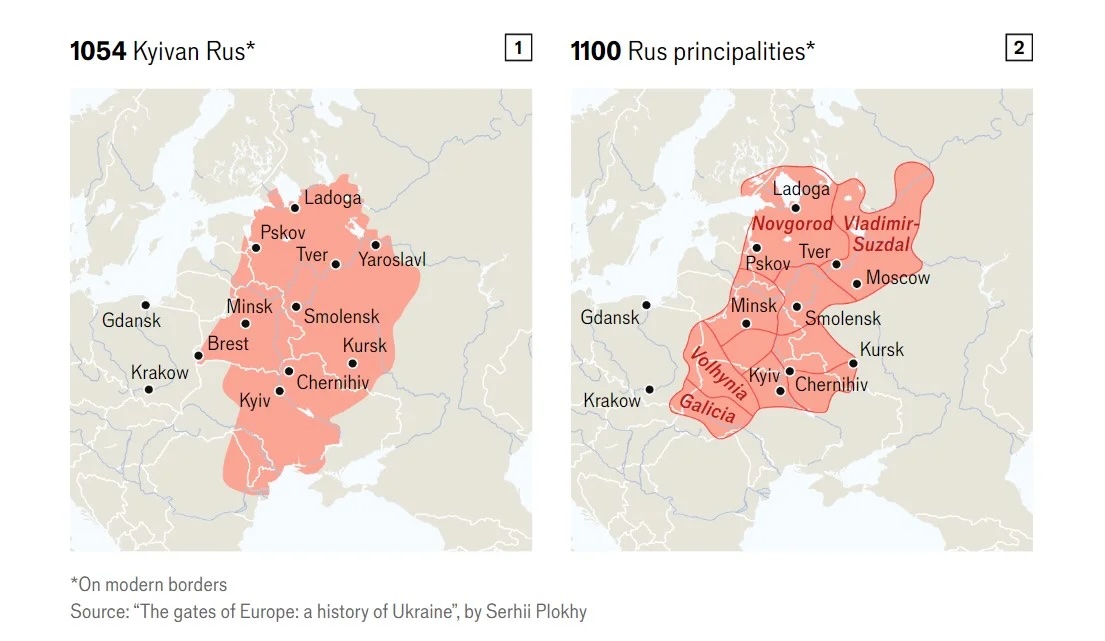

The state of Rus emerged in the Podniprovia

region under two powerful political and cultural forces on the local Slavs. The first was the Byzantine tradition, which spread north from Crimea. The second, the Norman tradition, flowed south from Scandinavia. In the 9th century, in the area where these influences collided, the future Rus was born.

The Rus people (after whom the state was named) spread widely throughout the territory of modern Russia, from the Gulf of Finland along the Volga river to the Caspian Sea. However, none of the cities in this territory, even the older ones like Stara Ladoga, ever became the centre of statehood. The first and only capital of the Rus that we know was Kyiv. And none of the regional capitals of late Rus could compete with Kyiv either in terms of size or importance.

Source: The Economist

This is why the state became divided into Rus “in general” and Rus “in the narrow sense”. The first term referred to the state as a whole, while the second referred to its core, Kyiv. A Byzantine merchant could go “to Rus” (the state in general), but so could a merchant from Novgorod or Volodymyr – and in these cases, it was understood that their route led directly to Kyiv. In its section on the year 1146, the Rus Chronicle includes the following passage: “And Sviatoslav, crying, sent Yurii to Suzdal and said, ‘My brother Vsevolod was taken by God, and Igor Iziaslav was captured. Go to the Rus land, to Kyiv.’”

Ancient Kyiv connects Rus and Ukraine. All the Russian capitals – Vladimir, Moscow, and St. Petersburg – are newly built compared to it.

Politics of Kyivan Rus. Democracy is in the blood

Although the Slavs had princes (known as “kniazes”) and the Normans had kings (known as “konungs”), Rus was not a monarchy. Slavic rulers were closer in status to parents than to kings. Militarily, the leaders of Rus were perceived as older brothers. Both the Slavs and the Scandinavians kept powerful remnants of their original military democracies. This is why the first princes of Rus were careful not to ignore the opinions of senior soldiers. The viche, a popular assembly in medieval Slavic countries that functioned as a city council, could refuse to go to war and could sometimes even overthrow the ruler.

In late Rus, differences between the political models in different regions became evident. In the centre and the west, a typical European process of the rise of the aristocracy took place. And if some ruler (for example, Prince Roman or King Danylo) rose above the boyars, a high class of society, it was due to his personal qualities, not his position. In the north, in Novgorod, they did not have hereditary princes: instead, rulers were selected by the viche.

Source: Ukrinform

In contrast, an autocracy began to take shape in what is now Russia, and the boyars lost their influence there. In 1174, rebels killed Andrii Boholiubskyi, but later, such forms of resistance became difficult. Autocracy was established in northeastern Rus even before the Mongol invasion. The Mongols only strengthened this old local tradition.

For the Ukrainian lands, the struggle for “rights and freedoms” was at the core of political history in the times of princes and of Kozaks – specifically, from the Lithuanian era to the end of the 18th century. In the 20th century, this political culture became even more potent.

Democratic Ukraine – which was even close to being anarchic at some points in history – is closer to the political system of Rus than authoritarian, and sometimes totalitarian, Russia.

Andrii Boholiubskyi (c. 1111 – 29 June 1174)

was a prince of Kyivan Rus who is known for organising a destructive raid on Kyiv. He is also considered one of the founders of what would later become Moscovia.Language. Ukrainian dots above the old “i”

For two hundred years, Russians tried to prove that Rus was inhabited by one common ancient Rus people. The imperial version of the myth says that these people continued to exist, and the Soviet version says the ancient Rus people became the ancestors of the “three brothers”: Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians. Each of these concepts assumed that political unity had to come from cultural unity.

In fact, if a “common culture” did exist, it included only a narrow layer of the Rurikids (the ruling dynasty of Kyivan Rus) and higher bishops. Most people in Rus spoke four or five languages, each of them as distinct as the modern East Slavic languages. This is confirmed by research into graffiti on the walls of St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv and birch bark manuscripts from Novgorod.

Specific features of the Ukrainian language that distinguish it from its neighbors already existed in the days of Rus. Where the Russians have “les” and “pech”, Ukrainians have “lis” (“forest”) and “pich” (“stove”). Ukrainians are now the only ones among their neighbors who say “kin’” for “horse”. Poles, Belarusians, and Russians use an “o” — “kon’”. Then there is “podcast”: oddly enough, Ukrainians almost decided to turn it into “pidcast”!

The name of the founder of the state of Rus was written both in graffiti and in chronicles as “Володимѣръ/Володимиръ” (Volodymyr), which is how it was pronounced. In contrast, the modern Russian version of “Vladimir” comes from an artificial Church Slavonic language.

Back then, the ancestors of Ukrainians also actively used the vocative case. The Ukrainian language still uses it today, while the Russians dropped it from theirs.

Even a basic linguistic comparison brings disappointing results for Russians: the modern Ukrainian language is much closer to the language of the capital of Rus (Kyiv) than Russian is. So it’s not surprising that during the times of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi (1595-1657), former Hetman of the Ukrainian Kozaks, an interpreter was required at negotiations with Moscovia.

Church. Openness vs. obscurantism

Ukrainian Orthodoxy was subordinate to Russian Orthodoxy for so long that people started taking its status for granted. In fact, the Moscow Patriarch uses the title “of all Rus” illegally, because the real Rus Orthodoxy is in Kyiv.

Faith and the Church came to Rus from Byzantium in 988. It is natural that the Kyiv Metropolitanate belongs to the Patriarchate of Constantinople.

The departure of the metropolitans from Kyiv to Vladimir and Moscow in 1299 meant nothing in an ecclesiastical sense. Due to political intervention, the Kyiv Metropolitanate was divided in two, but legally it remained united. In 1448, a separate Moscow Metropolitanate emerged. Through corruption and pressure, it gained the status of patriarchate in 1589. Kyiv remained under the rule of Constantinople, only becoming subordinate to Moscow in 1686.

Council of Volodymyr the Great with noblemen and his army at the adoption of Christianity by Rus. Miniature from the Radziwill Chronicle. Late 15th century.

As an autocracy, the state isolated Moscow Orthodoxy politically and culturally from the rest of the Orthodox world. This caused it to gradually degrade and acquire sect-like characteristics. At the same time, Kyiv Orthodoxy developed in competition with Polish Catholicism and flourished theologically (e.g., publishing polemical literature) and artistically (e.g., the Kozak Baroque architectural style). The clash of these two church traditions in the Romanov Empire after 1654 caused a massive shock in Moscovia and, essentially, a civil war known as Schism. The “Kyivans” came out victorious against the “Muscovites”, giving an impetus for Russia to develop.

Russian Orthodoxy degraded further in the 18th and 19th centuries when the government turned it into the “Department of Orthodox Confession”, essentially making it a government department. Today, the Russian Orthodox Church resembles less and less a Church, and more and more the Russian Ministry of Ideology, even having KGB agents at its helm.

Ukrainian Orthodoxy – democratic in governance, open to the world, intellectual, and oriented towards educated parishioners – is more similar to the Church of Ancient Rus than the authoritarian, closed, obscurantist Orthodoxy in Russia.

Dynasty. A disproven argument

The only real Russian argument in the dispute for Rus is a dynastic one.

After 1340, the rulers of most of the Rus lands came from the Lithuanian Gediminid family. But the Moscow principality, having overthrown Mongol rule, was ruled by the Rurik family – descendants, however distant, of Volodymyr the Great. Because of this far-flung link, during a conflict with Lithuania at the end of the 15th century, Muscovites started claiming they had rights to their “homeland” of Kyiv. And this worked – for a while.

The truth is that this argument expired in 1598 with the death of Fedor Ivanovych, the last (and childless) tsar from the Rurik dynasty. After him, the throne was occupied by representatives of close but separate families – the Godunovs, Shuiskys, and Romanovs.

However, even if the monarchy were restored in Russia today and someone from the Rurik family were to sit on the throne in Moscow, this would not be enough to claim Kyiv. Rus was always ruled from Kyiv, not from Moscow.

Modern Russia has the same relation to historical Rus as Romania (România) has to the Roman Empire (Imperium Romanum).

A distant land that was once colonised by a great power, a similar name the only remaining resemblance.

Ukraine, on the contrary, is the true descendant of Rus.