“Listen to the voice of Mariupol” — a series of stories of people who managed to flee from the besieged Mariupol. We continue the series with a conversation with Katia, the wife of an Azov serviceman who spent several months in a bunker at the Azovstal plant with her two sons.

Katia was born and lived all her life in Mariupol. Together with her husband, they planned to build a future there. Katia’s husband is a serviceman. A few days before February 24, he began preparing the family for leaving the city. Unfortunately, Katia hadn’t been able to evacuate from Mariupol before the beginning of the full-scale invasion, so she had to hide with her sons at the Azovstal plant. Only on May 1, after passing a filtration camp set up by the invaders in the village of Bezimennyi, Katia finally managed to evacuate through the humanitarian corridor organized by the UN. Now she’s relatively safe on the territory controlled by Ukraine. However, Katia’s husband is currently being held captive along with other soldiers who were holding the defense of Mariupol at the Azovstal plant, surrounded by Russian troops.

— My husband’s name is Sasha. We met when we were 17 years old. Since then, it’s been like love at first sight. We haven’t been apart. We have two children: Mark and Lev. My husband wanted our future to be in Mariupol and wanted to get promoted in his service role. We tried to save up for buying a car, maybe in the future for buying an apartment. We thought that our children will go to study at a good university.

Everything seemed to be fine, but 2014 came. Then, for the first time, everything turned upside down. And when he realized who had come to his land, he said, “I will not tolerate this.” And then he joint military service. First, he went to the National Guard, served there for several years, and four years ago, he relocated to Azov Regiment.

He had no military education, so he had to learn everything during his service. Sometimes he was not at home for eight months. And now, it’s like he was born to be a serviceman, as if it’s in his blood.

I’ve always been communicating with our children as if they were adults, trying to explain everything to them as it is. So, I said, “Dad is a military man now.” And for them, he is a great role model.

It seems to me that the Azov servicemen had been getting ready (for another invasion – ed.). They knew what could happen one day – either tomorrow, in a year or in eight years. They had something to fight for: their families, their city, Ukraine. In addition, they are all brilliant guys. They have very great leadership. They know what they are doing. My husband said, “Something will happen. Please, leave. Pick grandma, do something. Go away.” But he said that on the 25th, he would tell me what was the exact scale of the threat.

People started discussing what to do, collecting emergency bags. It was around February 21. He said, “Get ready.” So, I ran to look for the most necessary things. Immediately you face such a reassessment of values: what is important and what you can leave behind. Since we are experienced tourists, I put backpacks on the scale and counted how much I could take with me, how much I could take for children. And in two days, I was ready.

For me, the most difficult thing is that I forgot my wedding ring at home. I took it off when I was washing the dishes. And then we were getting ready in a hurry, so it remained on the shelf. Also, the albums with my children’s photos remained there and the photos of my mother, grandmother — everything was left there, all those albums. But I managed to take a large hard drive with me. It shows our whole life in photos and videos.

When my husband realized the scale of everything, he said that there was probably no chance to leave. He was called on February 19 or 20. And on the night of the 24th, it all started. I woke up from a very loud bang. About an hour later, Sasha wrote, “Get ready, go to grandma’s.” Our apartment is on the fifth floor, and hers is on the first floor and lives further from the city center. We packed up and went to my grandmother’s house that day.

Photo from Katia's personal archive.

On March 2, the power grid was turned off. There was no longer any communication. On March 4, we got woken up to because the house was shaking. We could hear that. In the evening, the military arrived and took us with them with saying, “Your husband sent us here. Get ready, you are going to the shelter.” We were taken to the Azovstal plant at night, driving without any lights. It was dark, so we couldn’t see anything. When we arrived, we were taken to a dark room and shown a place to sleep: it was one of the work shops at the factory. We stayed there until March 10, until our premises came under heavy fire. At that moment, we realized that we should immediately run and hide in the bunker. We were most worried when a tank fired our way on March 9, killing a woman and injuring a guy. The children didn’t see that, but they later saw the guy. He was shell-shocked, all black and gray. We provided him first aid. I covered the children with a sheet and told them not to look.

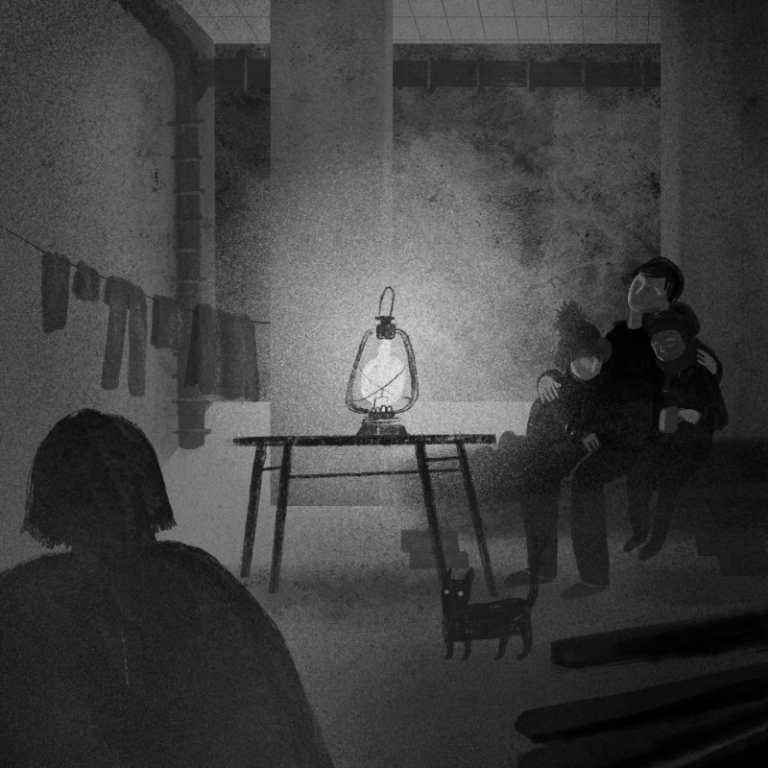

The next day, under fire, we fled to this bunker. There were 10 of us in the workshop, and 30 of us were already in the bunker. In the first few days, the younger son Lev would wake up and cry, “Mom, I dreamed that our house was destroyed” or, “mom, is everything fine with you? Are you all right there?” At such moments, I was hugging the children close to me, and we were falling asleep like that. Although I was shaking, I didn’t show it. We were lucky that my grandmother gave us mattresses, pillows, a fur coat, so we almost had a bed. Others didn’t have it. They assembled benches, made something, and searched for mattresses in the factory. In the bunker, the temperature did not exceed 14 degrees for two months. We had a fairly large supply of water in large tanks, but it was stinking since it was process water. The drinking water was bottled and carbonated. At first, we drank it, then our military brought other water.

We went down to the bunker on March 10 and stayed there until May 1. Men who cooked food ran to the basement under fire, where they built a fire place and cooked. The children and I were sitting in the storage room and waiting. The light could be seen from a few meters away. It was about ten meters from the door, and you needed to crouch down to see there was sun somewhere.

Photo from Katia's personal archive.

Photo from Katia's personal archive.

First, we brought all our supplies from home to the bunker: porridge, canned food, everything from the refrigerator, everything we had. The military also brought us some humanitarian aid while there was such an opportunity. These were the first days when there were no heavy attacks. Then, when we had already moved to the bunker, we took all the food. So, for two weeks, we held on to what was there. Subsequently, the military came and asked if we had what we needed, and tried to get something more. Mostly it was porridge, oatmeal, stewed food, canned food — this was the main diet. In the morning we could drink tea, at lunch we always ate oatmeal, and in the evening we already tried to make porridge with stew, so that at least some meat was there.

Photo from Katia's personal archive.

We knew there were air attacks. When you hear “Bang! Bang! Bang!”, then again — “Bang! Bang! Bang!” Those were Grads. “Grads” were small “sediments”, as we called them. And if the sound was like “frrrrrrrrrr”, then it was a rocket flying. You were sure it was a plane because it was buzzing loudly, you could hear it launching rockets. That was probably the most terrible thing. We know how tanks and mortars sound. Now, sometimes, I sit in the room, quietly. And I noticed that I started to hear electrical appliances humming.

Generators were brought to us there, but there was not always fuel for them. When there was an opportunity, some men had to run to the factory for fuel. When it was brought in, we kept them working for a few hours to charge our phones and turn on the lights. That’s how we saved charging on our phones. For example, I was turning it on once a day to look at the time, day, and I was immediately turning it off. We had car batteries, to which light bulbs were connected, so there was such a small light in the dark. We also had a kerosene lamp until the kerosene ran out a month later.

Photo from Katia's personal archive.

Photo from Katia's personal archive.

In the morning, we were trying not to get up until the men returned with hot water for tea. Some girls were trying to keep themselves in good shape — they were applying creams, doing manicures just to do something; someone was just waiting; others were gossiping all day. During the lunchtime, we were eating, cleaning up and just sitting and waiting. There was not much to do, I was waiting until the evening and going to bed.

Photo from Katia's personal archive.

There were toilets — ordinary toilets. But there was no water. Well, at least it was a sewer, not the pits. When we were washing dishes and doing laundry, we stored this water and then used it in the toilet. To wash ourselves, we had to ask men to heat water over the fire. We were washing ourselves in a small room where there was a drain, and it was freezing, so we had tp wash quickly, at least once a week.

I kept a diary to keep track of the days so that they wouldn’t merge into one mess. When we found out that we would go through all those Russian checkpoints and be examined, unfortunately, I had to burn the diary. There was a lot of information that I did not want to share with them.

There were about ten children in the bunker. They were spending all days running back and forth, making some pistols and submachine guns out of paper and tape, shouting that they would defeat the Russians. They were playing the Azov servicemen. In addition, we had books with fairy tales, and we had a tradition — every day before going to bed, we were reading fairy tales.

Photo from Katia's personal archive.

All the days in the bunker were the same, except when our military came. My husband hadn’t showed up for the first two weeks, and then he came to us. I was so happy! It turned out that he didn’t know exactly where we were, so he had to look for us. And from that day on, he tried to visit us, bring us something. Sometimes he would come every three days, sometimes he wouldn’t come for two weeks. The last time I saw him was on April 29.

On April 26, we recorded an appeal to the world asking to evacuate us. Our video has collected several hundred thousands views. And a few days later, the military came to us and told us about the possibility of leaving. From that moment on, we had been sitting on our suitcases and waited, waited, waited every day. Then it was already May 1, at one o’clock, the bus arrived as started picking people.

Photo from Katia's personal archive.

The exit from the bunker was like teleportation. Two months ago, we came in, and it was still snowing, but when we came out, everything was already green. When we left, we saw a small area — the Eastern district. There were charred black boxes. The inside areas of some houses were gone. Meaning that, where there should have been stairs at the entrance, there was nothing – a hole. I couldn’t believe my eyes: either there was a part missing, or everything was burned down. And no house was intact. Everything needs to be demolished and rebuilt.

On May 1, when our military arrived, we boarded a broken bus with no windows or seats. We were taken out of the factory and met across a bridge by representatives of the UN and the Red Cross. They walked us to the next bus. I think that was a bus from the so-call Donetsk People’s Republic. The Russian military was already armed there. They took us to Bezimenne. That’s where we were “filtered,” spent the night, transferred to buses and were taken to Zaporizhzhia.

During the inspection, the Russian military took everyone in turn to tents, where they checked things and sorted everything out. They were watching very carefully and asking provocative questions. I was a little more lucky: they didn’t check everything meticulously. They also took my phone, connected it to my computer, installed something, checked all the photos, correspondence, if any. When they found any connections with the military or police, questions arose. I had to undress because they were checking my tattoos. Then we went to the next tent, there were many tables, and at each one it was the same. We told them where we lived, where we would go, what our plans were. They looked at our documents, took fingerprints and photographed us. They also asked why we didn’t want to go back to Mariupol, “Do you know that there are fights going on in Zaporizhia now? There’s a war there. Where will you go? No one is waiting for you there. Go to Mariupol. It’s good there now, everything is being restored there, it will be great for you.” And so, I went through this filtration for two hours, for someone it was longer. They didn’t find anything in my possession, I hid everything. And no connection was found. So, it was easier for me. For who were found in some connection to military, there was more pressure. They threatened them and wrote to the military from their mobile phones on Instagram, Telegram, and tried to call.

We left the filtration camp the next day, it was May 2. By the time we got to Berdiansk, it was almost ten o’clock in the evening, and we stayed there at school. We were even able to wash our hair in the sink. Because we were going to Ukraine, to the city, we had to be pretty. On May 3, we already left to Zaporizhzhia and arrived on May 6, around five in the evening. All this journey from Mariupol to Zaporizhzhia lasted three days.

When we saw the Ukrainian checkpoints with our flags, we started applauding and shouting, “Hooray.” We were all waving, the kids were jumping in the bus. There was a feeling of “Finally! Here are Ukrainians.” I was happy, ready to hug and kiss everyone and say, “You are so cool!”

We promised to tell everyone what was happening in the bunker, what conditions our military was in, and what condition our city was in. We said that we need to convey to the world what was happening in Mariupol. We thought no one knew. Upon arrival, we saw how many people were meeting us. This was such a shock! Everyone always tried to feed us. I said, “I can’t eat that much, please don’t feed me, take me away.” And we were told, “Eat, eat, eat.” And then we were taken to shelter. Very nice girls are working there. We were given clothes, everything was given. And the psychologist was also worried about us. In general, I wanted to clean myself up, standing under a hot shower, and, of course, to go for a walk, see green leaves, get some air, so that my children could run around. Although we were told that no one was waiting for us here — it was all a lie, everyone was waiting for us. And this is a different world altogether, different from what it was two months ago. People have changed. This is a very different Ukraine, I think. It seems to me that Ukrainians have united, felt who we are, why we should support each other, why we should be together. We felt that it is our responsibility to be Ukrainian.

Now we are temporarily in Dnipro. I like to walk in the park with my kids. I like to hug them, then a certain aura is created around me, like a barrier from the whole world, from all adversities. It is important for me to be in the sun every day, and especially for children. Of course, I want to go home. I hope to go to Mariupol, to the sea. I never thought I’d miss the sea…

slideshow

When my husband last wrote to me, almost a week ago (the interview with Kateryna was recorded on May 21. — ed.), they have already begun to take out the military from Azovstal. He said that everyone would be taken out one-by-one and that there would be no communication in the near ftp. He told me not to worry. He said that he would be in captivity, laughing, “In life you need to try everything” — as always, in humour. Furthermore, he said that if they call and demand a ransom, I mustn’t fall for that and should not give any money.

Our children have already defeated Russia in their games a while ago. They have a favourite song. They brought it to us in the bunker, it was a hit for us, it talks about the corpse of a Muscovite. And there’s this chorus, “La-La, La-La.” They have long wanted to be like their dad. He is a role model for them. Their dad is strong, smart, always serious but cheerful. The guys are saying, “I will be like dad, a soldier.”

Being a military wife requires self-control, some positive thinking, and being able to wait and hope for the best. In general, when my husband said, “I’m going straight to the war. I have to go” — I saw in his eyes that he would not forgive himself if he did not leave. I had to support him in this as much as I could, as much as possible. And I did. I have always thought that each of us has the right to do what they consider to be necessary. Everyone is entitled to express their opinion, but to not prohibit to do something.

The most valuable thing we have is our lives, the lives of our children. Not apartments, not real estates, not computers — such little things mean almost nothing. Before the war, I was sad at home and I didn’t know what to do. There was some melancholy. And now I think, “God, I will be happy every day for being alive, for the sunshine — that’s all I need.”

Mariupol is a city of hope for me. When Mariupol will come back under control of Ukraine, of course, we will go there. Of course, we must contribute to its restoration. I am strong now, with an unshakable belief that the victory will definitely be ours.