Listen to the voice of Mariupol — a series of stories of people who managed to flee the besieged city. We start with a snippet from a phone conversation with Masha, a local who evacuated with her family on March 16.

Masha has been living in Mariupol all her life. Her windows look out onto the children’s Polyclinic destroyed by Russian invaders’ airstrikes on March 9. Masha and her husband Slava have three sons and a dog. During the siege of Mariupol, her family and the other 40 residents of their house spent most of the time in a shelter, hiding from shelling. At the same time, the city was cut off from gas and electricity supply. There was also a shortage of food and drinking water. On March 16, they managed to leave the city in a neighbour’s car in the direction of Yalta, a village located 33 km from Mariupol.

“First, they cut off the running water, electricity, and gas. On the first day without gas, people were still full of enthusiasm. Everyone went out into the yard to fry potatoes. It was like the May holidays. There was no anxiety yet because there were no attacks.

Our yard was small. Four entrances, everyone knows each other here. Someone lived in the basement already, someone — on the first floors, someone recently moved in with relatives. Everyone got to know each other, but to be honest, there wasn’t much time to remember the names.

We lived on the fifth floor. I was afraid to stay there with the kids, so we decided to go down to live with a neighbour on the second floor. From the first night, we often went to the shelter. My husband Slava brought electricity and running water there. Our neighbours brought a mattress. And we began to take down things there slowly. And when the maternity hospital was bombed, we got two small mattresses for children into the shelter and started to stay there every night.

Everyone in the shelter had flashlights and candles. Everyone was distracted as best they could. We played cards and checkers. We also read books with the children. I took the Harry Potter book with me, so we read it with a flashlight. We supported each other. There were about 40 of us in the shelter.

Each of our days started with cooking. The men went out around seven in the morning to lay out a fire near the entrance. We took out the grill grates from the oven and pans and pots. Everything was black. We cooked food on the fire. We took water from the water utility. At first, it was bottled — both running and drinking. Firewood was brought wherever possible. There was a building construction site next to us. It was the city council burned down, which they began to rebuild to open in September. There are many different pallets left there. People took out old furniture, broke and brought here branches.

When the looting started, the locals devastated a store near our house, “Vaniushka’s sweets”. All the cookies were taken out, and we also ate those cookies. Slava went to the pharmacy, but people took everything out of there. All he took were vitamins. We ate them because there was nothing else left.

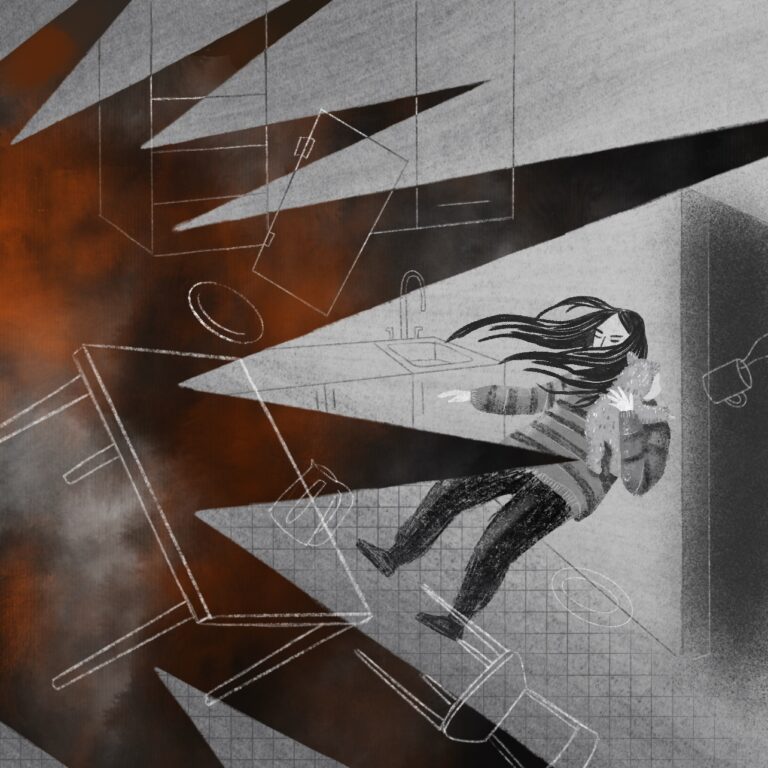

On the airstrike at the hospital, we were in the kitchen. Our neighbour Vika brought a teapot from the street, so we decided to drink tea. When they bombed, I was standing in the kitchen. Yarik, with the youngest Vladik (Masha’s children. — ed.), sat on the couch with Vika. The only thing I caught a glimpse of was a flash. I just shouted, “Get Down!” but no one made it. The blast wave just knocked us down.

The glass flew out because we had taped the windows well. Therefore, there was no debris. We fell to the floor with my nine-month-old son, Yarik, on top, then my neighbour and me. It didn’t even occur to me that it was an airstrike. I thought it was so-called grads that fell somewhere nearby. I decided to run to the shelter in the apartment, a small storage room near the load-bearing wall.

Not only that, but I trained the children for a long time as soon as it became known that the armed forces were being drawn to the border. Having the experience of 2014, I know what to do: fall, cover your head with your hands and open your mouth so that you don’t get concussed. Children know this. They immediately get down and cover their heads with their hands.

Zhenya was the first to run into the pantry. Yarik followed him. I picked up my youngest son in my arms, and my mistake was getting up. And when there was a second bombing, the blast wave threw me into the wall. I scratched my hands. The child hit his head, but it was soft because it was drywall, so my hand was harmed more. Somehow I ran to the pantry and lay down with my whole body on top of the children. I probably lay there for about twenty minutes until everything was quiet.

When there are bombings, they follow each other. The interval between them is small. If it is ”grads”, then the sound is similar to peas falling — pam-pam-pam-pam-pam — that is, there is a specific interval. And if there is an airstrike, then there is a whistle. But that time, there was no whistle.

After the windows in the neighbour’s apartment were blown out, the air temperature became as low as outside. So, we lived in the basement. The temperature there ranged from 9 °C to 12 °C. Maximum -12.9 °C because many people were there, breathing, closing the doors at night, those between shelters. To warm up we put on warm clothes, slept dressed in outerwear and covered with warm blankets.

They slept at the time between shellings. As soon as I had the opportunity, I immediately fell asleep. It was vital for me to sleep because I am breastfeeding my youngest son. There is more milk during sleep. I entertained myself there calmed myself down as much as I could. It was horrifying when they were shooting somewhere nearby.

I was only thinking about my children those days. I was thinking about how I would arrange my life in the future so that this would never happen to them again. There was a period when I blamed myself for not leaving on February 24 (the beginning of a full-scale war of the Russian Federation. — transl.), at least to Dnipro. I was afraid then. I had the opportunity. But until recently, like everyone else in my surroundings, I did not believe there would be such a meat grinder. No one could even imagine. I thought it would be like in 2014. I thought it was a matter of days. And that there would be some agreements that would be respected so that the military conflict would somehow be resolved. But this is just a large-scale genocide. I can’t call it anything else.

We left town after a boisterous night. Then everything was shaking. It seemed to bomb every two minutes. An hour of silence, then another shootout. Two hours of silence, and again. You sleep and don’t know what will happen next. The walls were shaking. Dust was falling on my head. The kids were all dirty. We pressed into a neighbour’s car at 10 a.m. There were nine people, a dog, and a cat. We drove for about an hour — no one shot at us, but it constantly shelled around when we were driving. The Ukrainian military blocked the street where we live. Twenty kilometres from Mariupol, at the entrance to the village of Mangush, there was an improvised checkpoint with the military. They were armed with machine guns and made “pass” gestures.

There were numerous questions from children: “Mom, why is this so, why are they shooting, and what they didn’t share, and when will it end…”? I admit that I don’t have an answer to many questions.

Lying in the shelter, I repeatedly imagined that I would return home after some time. I thought about how I felt. That was helplessness. That was the desire to cry. These were what I had found. I do not know how long it will take to restore all this. Not a year or two. Now it is difficult to predict anything. But there are children. Children and I are the top priority.

I am afraid to go to Zaporizhzhia after there was information that “grads” shot the evacuating column. However, if you don’t try it, you won’t know. If there is even one chance to leave, you should take it. Because stuff is just stuff, an apartment is only an apartment. And life is one. And how we live it depends entirely on us.”

When recording this conversation, Masha and Slava were looking for transport to go to Zaporizhzhia. Eventually, they succeeded. After a shortstop, they set off again. As of now, Masha and her family are heading to the west of Ukraine.