“Listen to the voice of Mariupol” is a series of stories of people who managed to flee from Mariupol. We continue the series with a conversation with Yulia Kostenko, a Ukrainian-speaking native of Mariupol who wrote a war diary during her time in the besieged city.

Yuliia has been a volunteer at Ukraїner since 2018, translating materials into French. Before the war, she also worked as a teacher. When the pandemic began, Yulia returned to her home city of Mariupol from Lviv. There, she started working at a language school in a team of education professionals and teachers. Yulia spent the first weeks of the blockade with her parents and dog in their flat. However, later on she had to leave her home. On April 11, she and her family left the occupied city.

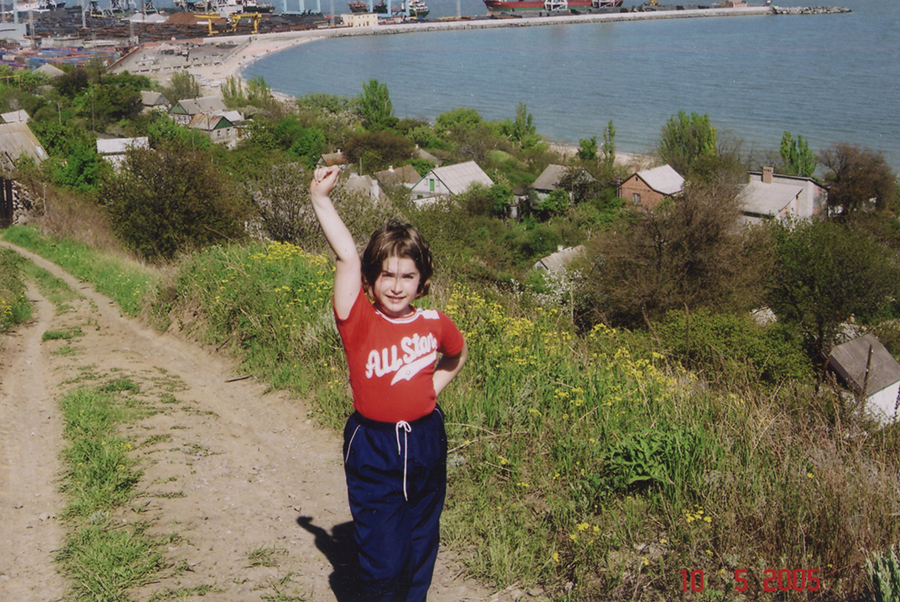

“The city of my childhood… I have memories of the seaside. During the summer holidays, I would visit my grandmother, who also lives by the sea. I mostly remember the sea, and probably my neighbourhood, which is quite close to the city centre. I remember the tree near the entrance to my building. It was great to climb up it and feel super grown up. And I can’t say I was afraid of it. On the contrary, I really liked it. If I hadn’t been teaching, I probably would have been doing rock climbing.

Photo from Yulia's personal archive.

I used to speak Russian in Mariupol. And then one morning, I woke up and was sick of it. Plus, I worked in the education sector. And I just knew that this was missing for me personally. So instead of dictating to my students ‘yablaka’ (‘яблоко’, Russian for ‘apple’ — tr.) I just started saying ‘yabluko’ (‘яблуко’, Ukrainian for ‘apple’ — tr.).

After that, there was a greater interest in what Mariupol was, and what Mariupol’s sense of Ukraine was like.

(In 2014, the Ukrainian Armed Forces were able to drive separatist and Russian forces out of Mariupol, preventing it from becoming occupied in the name of the ‘Donetsk People’s Republic’. These events made the city particularly famous all around Ukraine. The wider Ukrainian society grew curious about the city, its people and their strong sense of belonging to Ukraine, which held the city within the country in 2014. – ed.)

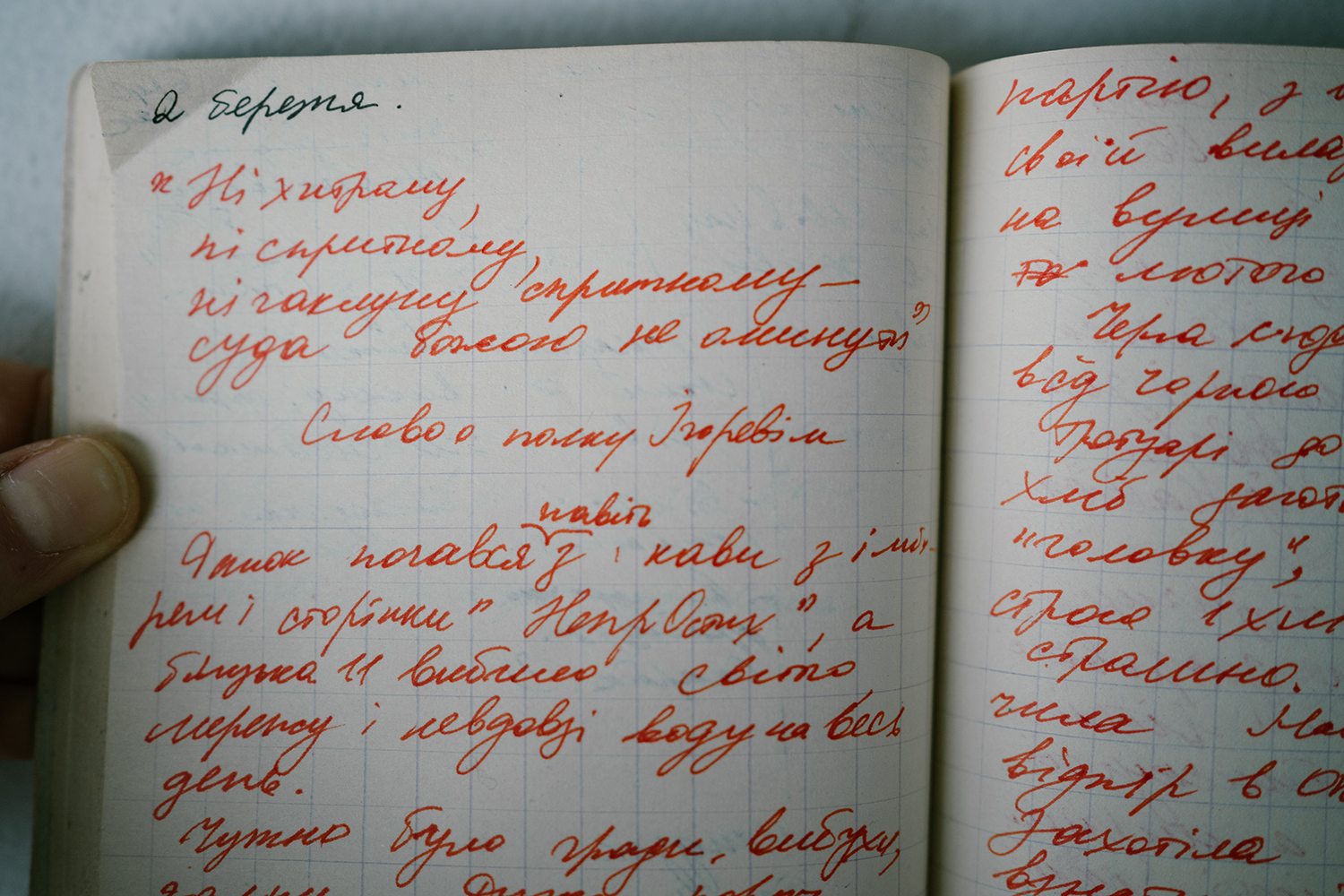

Very different kinds of people live in Mariupol. My grandma is from the Ivano-Frankivsk region. And she lived quite close to Mariupol. I’ve always enjoyed spending time with her. Our city is mainly Russian-speaking. Now this situation is somehow changing, and continues to change. Thanks to my granny, I learned about Ukrainian traditions that I probably would never have learned about without her, just living in Mariupol. I was always interested in talking to her because she knew some great words I would never have heard on the street. For example, I recently asked her: “Gran, how would you say that it’s cold outside right now?” She taught me the word ‘studenO’ (a lesser-known synonym of the Ukrainian word ‘kholodno’, meaning ‘cold’ — tr.). I started writing these words down. In my diaries I even have a separate page for Granny Melania’s lexicon. For me, language is such a huge layer of culture. You can say ‘banka’, or you can say ‘baniak’ (Ukrainian for ‘jar’ — tr.). You can say ‘strybaty’, or you can say ‘plyhaty’ (Ukrainian for ‘jump’ — tr.).

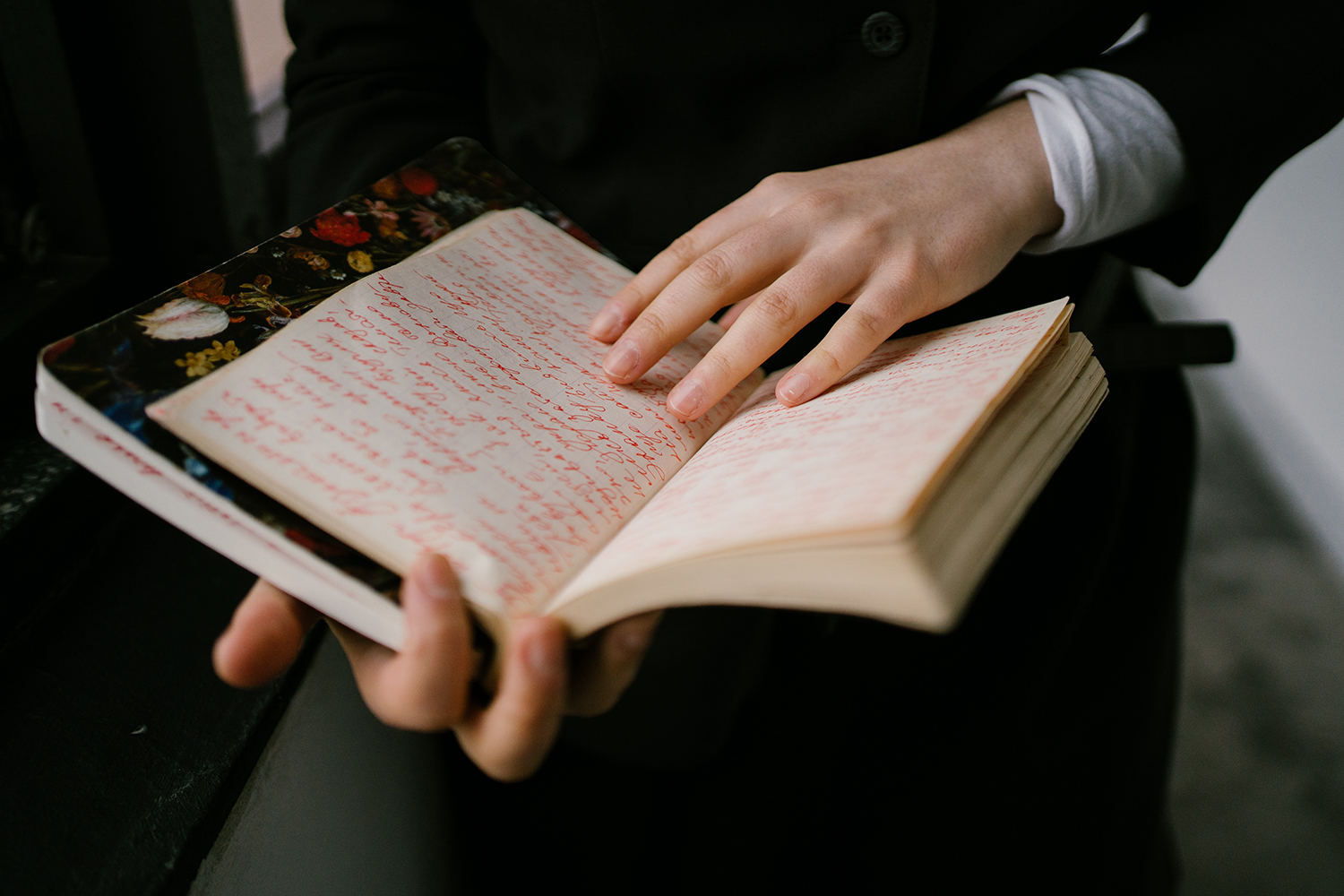

I’ve always been doing things like this: writing something, making notes, keeping a diary. It’s just that when I see that my grandma is already getting old, I want to write down these moments that I can come back to later. I’ve been writing a diary ever since I was a teenager. I do it because, through words, I can experience reality, experience the world around me, and this is crucial. Some people start drawing or singing about it. And for me, writing is one of the ways to express myself.

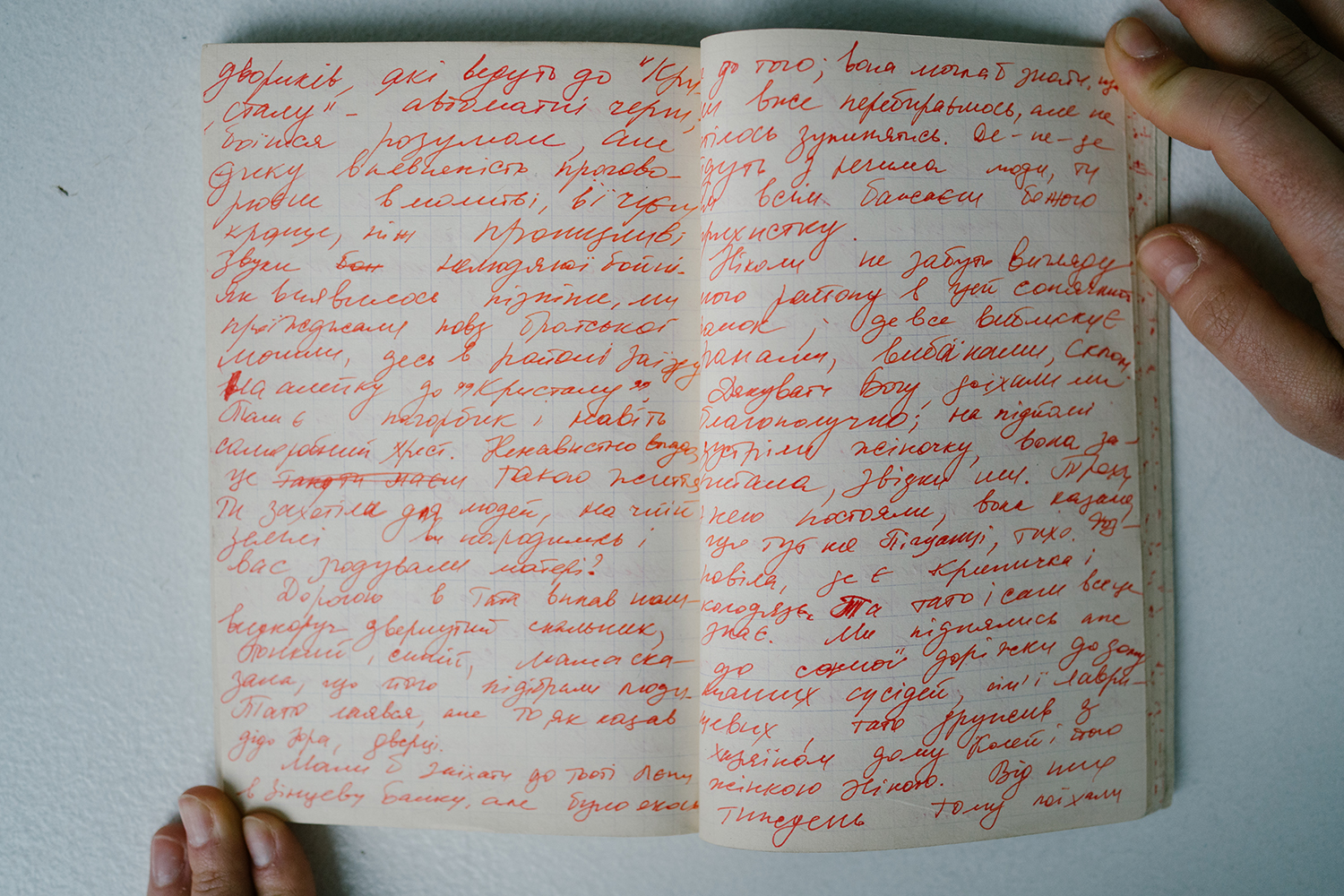

From the first day of the war, I realised that historically important events were taking place, and I couldn’t help but write it down. Moreover, in those conditions, writing for me was the most appropriate and the simplest thing to do, because all I needed was a pen and paper. First, writing things down really saved me. And second, it’s something that is emotionally charged. I would mainly write when I had access to a light source of any kind. I would either light a candle, if it was already getting dark, or else write during the day. It was also what you might call a quest. First you sit down to write somewhere near the window, and then you hear that something has flown past you, and you grab everything and run to the bathroom. And when all the military actions around you subside a little, you finish writing by candlelight.

When there were military vehicles and equipment near our house, you could hear everything very loudly, so we made a shelter in the bathroom. We threw all the carpets there and hid underneath. Sometimes, we would fall asleep there. Between 5 am and 6 am on the morning of March 25, the next-door building burst into flames. We were hiding in the bathroom, sitting on the floor. Later, we had a hurried breakfast and a cup of tea or coffee, and rode bicycles with our things to grandma’s place by the sea. It was about 8 am. We loaded everything onto our backs, but my parents were the most heavily-laden, no matter how much I pleaded for them to pass me at least one bag. There were eight or nine of us in total, including our dog Lord.

Photo from Yulia's personal archive.

We took the usual route to grandma’s, but everything around us was destroyed beyond recognition. For the whole duration of the war, I had just been sitting in a flat and didn’t even know what our neighbourhood looked like. On Budivelnykiv Street (where I grew up), there were two buildings with all the windows broken and glass lying everywhere. At the crossroads with Bakhchyvandzy Street, everything was completely shattered: shops, bars, dangling trolleybus wires that you had to avoid. There were terrible potholes in the asphalt. Closer to the bus stop, near the market, there was a pothole almost as wide as the road itself. And all around, you could hear the whoosh of the infernal ‘Grad’ missiles. Towards the courtyards that led to the ‘Crystal’ (a local café), you could hear machine gun fire. In your head, you’re afraid, but you say a prayer with crazy confidence and hear it more clearly than the piercing sounds of the inhuman massacre. It later turned out that we were riding past a mass grave, somewhere near the entrance to the alley leading to the ‘Crystal’. There was a mound and even a handmade cross. I had never felt that way in the modern, 21st-century city that was so lively, renewed, pulsating with energy. Never before had I felt so strongly like I was living in the Stone Age.

Thank God we got there all right. I was so grateful to have such kind neighbours. They got on very well with our grandma. We met Gran. I hugged her. She was very pale and tired. The neighbours said she had been hiding for a long time and really needed support. She even exercised every day by walking up and down a rather steep staircase. That was an intense workout for Gran. We were sitting in the yard, taking Lord for walks, and going to see the neighbours. And, for the first time in ages, we were feeling relieved. All the neighbours and friends who came to see us in the yard that day were interested in us and our neighbourhood, and told us their stories.

We heated water for the first time in a long while, and it was such a relief to finally be able to wash yourself properly. But at first, you’re tired, your head is full of other thoughts. And only later, after you’ve done it a few times, you think: “Oh, damn, this is hot water.” Throughout March, the average temperature was approximately -8°C to -10°C. Then, for a couple of days, it was -5°C, so you would go, “Oh, it’s getting warmer!”. Then, -10°C again. So it was really freezing cold in our flat. We had a clock that also showed the temperature. First it was 3°C, then 2°C, then it decreased by degrees. We lived at zero degrees for several weeks. My feet were the most freezing of all, because I barely left the house. I just ran around the rooms and did a little tap dance to keep warm. I would always sleep in ten sweatshirts, a fleece and socks. We would warm each other up. The mutual support in my family was so powerful the entire time. I’m proud of us all. My family has always been very important to me, and now the relationship has reached a whole new level.

Unfortunately, from March 22 onwards, it also got very noisy by the sea. Then it got noisier with every day. And you’d realise that there was now no safe place anywhere in the city, even in the area that was still quiet yesterday. So then we did all that we could to look after each other’s health — first mental, then physical — making tea, keeping each other fed, scratching each other’s backs, hugging, and so on.

It was April 7, the celebration of the Annunciation. It was an exciting day because a husky dog snuggled up to us when we went out into the yard. “You meet a dog on April 7, on Annunciation,” we said, creating positive superstitions for ourselves. We started saying, “Oh, this is a good sign,” a sign that soon we would somehow be liberated, and would be able to move around safely. So we left on April 11. We left at 9 o’clock, in a car belonging to the friend we’d been staying with. We went via Azovska Street, but the Russian military warned us that further on there was fighting going on. We went back. Dad went on a reconnaissance mission up the hill by bicycle – he said the coast was clear. We got into the car, crossed the hills and the plains, then drove to the checkpoint and underwent a real interrogation.

The checkpoint was right at the exit from Mariupol. I personally experienced humiliation at their hands. I lived through this interrogation, and I think it may push me to do some real work on myself. They intimidate you, they humiliate you — in short, it wasn’t the friendliest conversation I’ve ever had. However, we survived this not particularly sweet conversation and went to Melekino, which people call Muliakine. Dad arranged a place for us to stay. We spent the night in Melekino (we immediately checked into a boarding house). As Dad said, it was a budget option, but that didn’t matter because for us, it was on another level. We were amazed at the hot water in the taps, the electricity, and the fact that we could charge our phones. On the balcony, you could look around and listen to the sea and the unfamiliar silence.

Dad arranged for us to leave at 5 am: we just had to sleep through the night and get moving again with renewed strength. At the designated time, we left with a really good driver. We were in a convoy of two cars. My mother and I spent the whole time praying. And near the town of Chervone Pole, burnt-out cars were scattered on both sides of the road. And you realise that this was a convoy that drove by perhaps a week ago. And it’s all turned into metal scrap. These are such deeply wounded places that you realise how much of a miracle it is that you are now getting out. Even then, we felt such a powerful sense of gratitude for everything. Even just for the fact that we were unharmed. We were so lucky that my mother and I said that it was all just God’s will. I remember that whole journey with a constant tightness in my stomach, in a state of prayer.

After getting through 12 checkpoints, we reached Zaporizhzhia, where we stayed with my friend and her parents.

I brought my diaries, postcards from friends, and my ‘We are with Mariupol’ badge with me to Lviv. I brought my books: Taras Prokhasko’s ‘The Unsimple’ (‘NeprOsti’), Myroslav Dochynets’ ‘Children Of The Ferns’, and a collection of poetry by my friend Iryna Zahladko. And a book I have to return – ‘Peer Gynt’. I took my prayer book too, which I had started writing by hand. I also took a drawing by the girl who sheltered my parents and me in Zaporizhzhia. Her mother painted me a watercolour as a gift, a picture of me and my dog. I mean, these are objects that give me strength. You take the things that light you up.

I had a short list of places I would like to visit under the hashtag ‘victory’. I wanted to post it somewhere, but I haven’t got around to it yet. I wanted to visit a rock club in Lviv, and in Kharkiv, the square and the philharmonic hall. Living in Mariupol, I learned about everything at a distance. After moving and travelling around Ukraine, I started to discover that our country has great festivals. We have so much of everything, we are so rich… If once upon a time you had a dream, to-do lists, lists of places to visit, now you can’t postpone anything. We have to live right now.

How do I envisage our victory? My first thought is that all the cities that have been occupied should be Ukrainian. That’s how I imagine this celebration. After victory, I think Ukraine will become a tourist attraction. Every city in the country will become an emblem representing something of its own.

Compared to Russians, Ukrainians have a sense of value. A sense of the value of our history, culture, and art. We have a very caring, very sensitive attitude to this. I do not think Russians have this, and now they lack it more than ever. But Ukraine is breath itself. And love. And people.”