The art of vytynanka – or papercutting – first appeared in rural villages in Ukraine in the middle of the 19th century, as a form of home decoration. For a long time, it was considered to be a dying art. However, Dariya Alyoshkina, a craftswoman from Lviv, has found a new way to draw attention to this Ukrainian craft, creating vytynanky for modern interiors, public institutions and book covers. She also creates large vytynanka curtains that have won her fame in Poland, France and even South Korea.

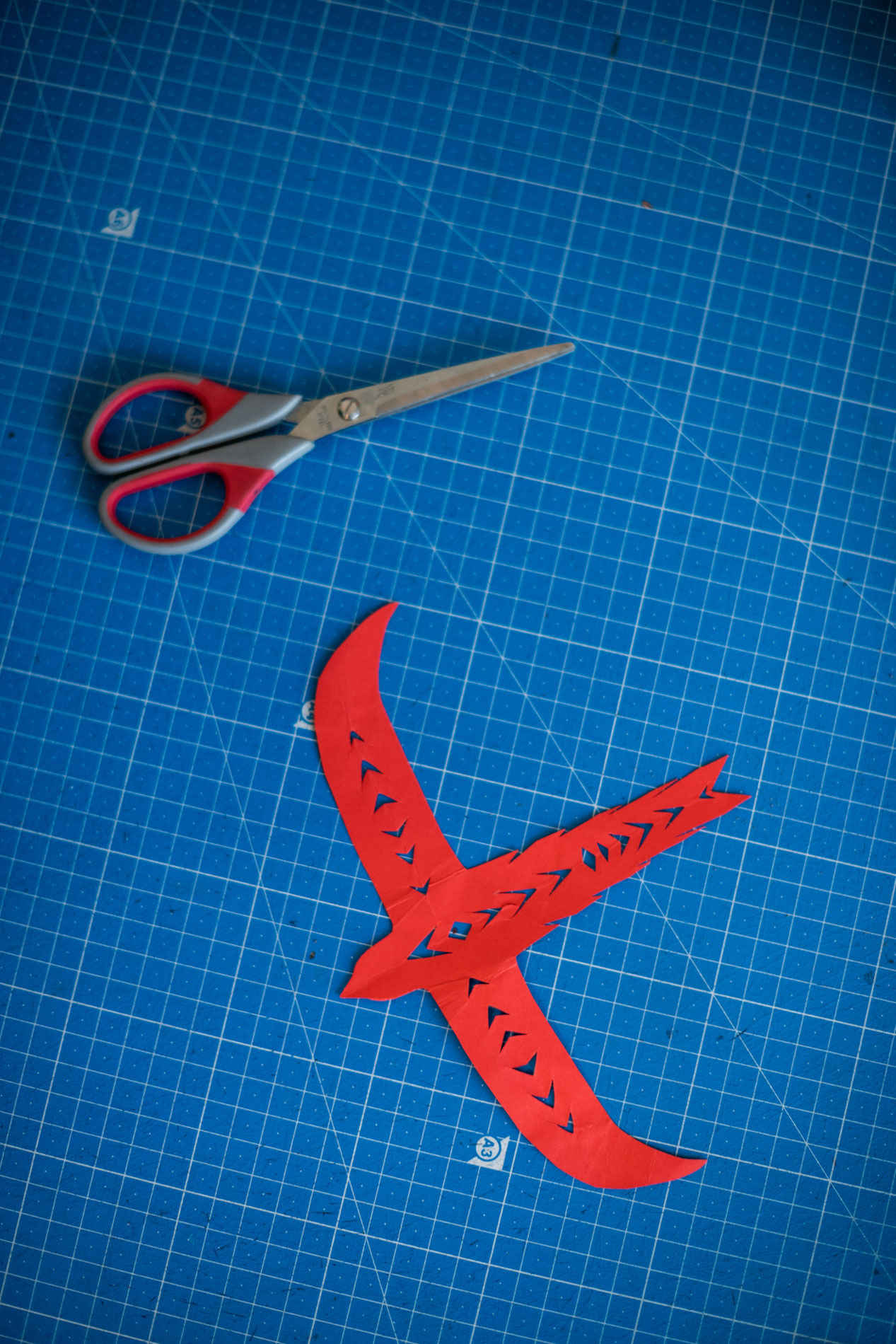

Vytynanky are decorations for the home, cut with a knife or scissors out of white or coloured paper, in the form of lace or silhouettes. The word is derived from the verb ‘vytynaty’, meaning ‘to cut out’. Traditional paper vytynanky were made with geometric or floral patterns, though they can also be found in the form of animals, people, everyday objects and houses. The paper was folded anywhere from twice to eight times. It was a cheap and easy way to decorate the home for celebrations.

In the past, vytynanky were used to decorate windows, walls, hrubky (stoves with a ledge for sleeping), shelves and stoves. Traditionally, a vytynanka tells a story of village life: celebrations, weddings and births.

It is believed that vytynanky originated in China some time between the 7th and 12th centuries. Researchers consider the prototype of the Ukrainian vytynanka to be the ‘kustodiya’ — a small piece of white paper with laced edges that was used as backing and decoration for official stamps in the middle of the 16th century. Only the edges were cut like lace; the centre was left for the stamp to be printed.

The vytynanka in its classic form became well-known in Ukraine in the 19th and 20thcenturies. Though they can be found all over Ukraine, they are most common in the Carpathians, and the Podillia and Naddniprianshchyna regions. The images and their place within the house varied from region to region. For example, in Podillia, vytynanky were used as wallpaper, carpets or curtains. In the Carpathians, people decorated the walls around windows and tie beams (beams that support the ceiling of a house — auth.).

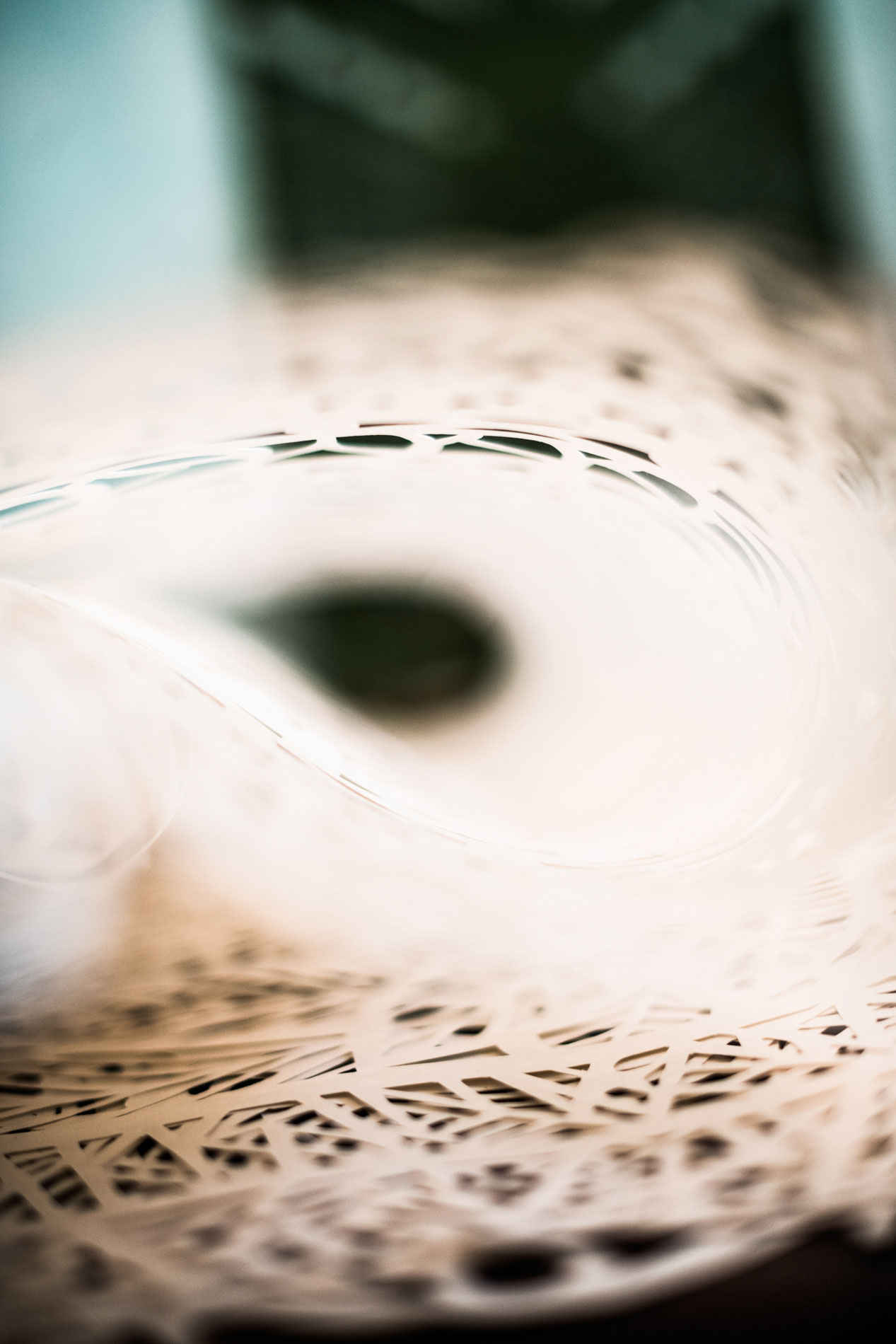

For celebrations, vytynanky were made in the form of snowflake-stars, crosses, periwinkles or angels. The vytynanka in the form of a cross was a talisman and was attached to the tie beam, where a baby’s crib would usually be placed. Shelves and sideboards were decorated with vytynanky that looked like lace doilies. Vytynanky representing the tree of life were hung in the spaces between windows.

In the 1960s and 70s, colourful industrial fabrics, carpets and other forms of interior decoration displaced vytynanky from everyday use. From then on, vytynanky were used only occasionally, as seasonal snowflake decorations for windows and Christmas trees.

Dariya

Dariya Alyoshkina’s childhood was spent in the Podillia region, where vytynanky were popular and had not disappeared from use. Growing up in a creative family, she too chose a creative path. She graduated from the V U Shkriblyak College of Applied Art in Vyzhnytsia, and Lviv National Academy of Arts, with a master’s degree in monumental and decorative sculpture.

Dariya was also the founder and director of the “Dyv” shadow theatre in Lviv, which often used vytynanky in performances.

Nowadays Dariya isn’t only a craftswoman, but also the mother of a large family. It was difficult for her to continue her sculpture practice at home after the children were born. But she wanted to grow creatively, and to combine this with motherhood. Then Dariya remembered vytynanka, which her parents had taught her in childhood. With her mother Lyudmyla, she had often made vytynanky for school contests, or just to decorate the house.

Dariya decided to perfect her skills in this already-familiar technique, and make something different. Her works are remarkable in terms of their proportions: she makes vytynanky that measure several metres across.

— I started to make large-format work – I guess you could say that’s how I caught people’s attention,” she muses. “Then people began to find out what vytynanky were, to realise that we had them in our culture. In 2008, vytynanka was considered a dying art form in Ukraine. Because they’re made of paper, they can’t be preserved – well, if it hadn’t been for certain historical events, it would have been possible to preserve some examples.

Dariya adds that she “occupies a neutral niche among vytynanka makers”, as there are some people who have devoted their lives to the art.

— I’m not exactly reviving these traditions, but I’m drawing attention to this art form and reviving it in some way,” she says. “I mean, I don’t know the most authentic motifs or methods. Basically, it’s all very simple, because the material is readily available and anyone can learn the craft.

In vytynanka, Dariya has found her new creative direction, one that she can combine with child rearing, allowing herself a few minutes at a time to enjoy working with paper.

— Vytynanka has been a lifesaver for me; it saved my creativity,” she says. “I’m very happy that I’ve found myself in it, as I have this inner need – perhaps inherited from my dad – for fulfilment. Only then do I feel truly happy.

The creative process

There are four different techniques for making vytynanky: lace (made from a single sheet of paper, with the image cut away), silhouette (with the image silhouetted), single (from a single sheet), and complex (appliqués made from several sheets of paper).

Vytynanky can be created with scissors, a special knife or even by hand. The maker either sketches out the image or cuts it out directly, folding the paper several times to form patterns. All Dariya’s works are symmetrical, as that’s the way she was taught.

— A lot of people make them without folding, but I fold,” she explains. “I also sketch out the image in pencil. For example, we sketch out the pattern here, and our hands act as scissors. It’s said that they were made this way on days when it was forbidden to use a knife inside the house. So, on certain holidays when housewives couldn’t pick up a knife, they made quick vytynanky by tearing the paper instead.

For this method, the paper first needs to be crumpled in order to make it softer, and then the patterns are torn out without scissors or a knife.

Dariya says she sees a kind of magic in folding paper for vytynanky, because you don’t know what you’ll find when you unfold it. She cuts out her vytynanky with a knife similar to a lancet, with replaceable blades. Sometimes she has to replace the blade 5 or 6 times in the process of making one piece.

Dariya uses a dense material (banner canvas) to prevent her works from tearing and enhance the presentation. While sketching out the designs, she plans where the lace will be, so as not to overload the paper and make the vytynanka lopsided.

— I have a system that I devised for myself,” she reveals. “But now there are plenty of plagiarists who think this is the way it’s always been done.

In order to cut a vytynanka out of rigid paper, Dariya holds her knife so firmly that her hands hurt afterwards. She works both sitting and standing. According to her, the most important thing is to have a plan for cutting the lace, so it won’t tear.

Dariya can spend anything from 3 to 5 days on one big curtain: this is a much longer process, due to the large size of the paper and her far-from-ideal working conditions:

— It’s a little hard for me, because I don’t have my own workshop and I make everything in these conditions. It’s really quite limiting: you want to start a grand project, but then you realise that you have constraints, that you don’t have space.

Don’t fear the paper

Besides the scale of her works, Dariya pays close attention to the images she uses. She admits that images of women, especially of Berehynia (a goddess in Ukrainian folklore), are the most frequent. She attributes this to her long-standing interest in traditional motifs, which dates back to her student years at Vyzhnytsia College. Carpet making and tapestry were taught there, and Dariya claims that this experience has helped her a lot in creating vytynanky. She explains why she particularly likes to make big curtains:

— Some time ago, people used to believe that decorating the windows with vytynanky would prevent evil from entering the house; that a vytynanka in the window worked a bit like a sieve. That’s also very interesting – a magic ritual. I really like these curtains – in big, nice windows, they almost look like stained glass.

Dariya says that for a long time, Ukrainians were afraid to buy vytynanky for their interiors as paper is a material that is considered fragile. Some are also afraid to work with it, because they are afraid of spoiling the work.

— You really need to feel it somehow,” she says. “Since paper is wood, I think it has a soul. I find it more difficult to work with artificial materials. But paper is so alive for me, and when you cut images out of it, it’s so interesting to observe the process.

A format that conquers the world

Dariya’s works no longer look like classic vytynanky. Her curtains travel more than she does herself, to places as far-flung as Germany, Poland, France, Belgium, South Korea and the USA. At her exhibition in Seoul, half the works on display were bought up by visitors; one was sold to the prime minister of South Korea.

— When we arrived, we got the feeling that there was paper in each house,” she enthuses. “They have paper lamps and other paper installations. It must be the homeland of paper; they have a great attitude to it.

Often Dariya travels to Poland for master classes. She says people there are also interested in paper and the art of vytynanka. She travels with her musician husband Hordiy Starukh — he brings lyres, and Dariya brings vytynanky. The creative couple often collaborate on projects, which provides inspiration to both of them.

Alongside her foreign projects over the last several years, the volume of orders and offers of collaboration from within Ukraine has increased. Two of Alyoshkina’s vytynanka curtains adorn Lviv City Hall, and the publishing house “Staryi Lev” selected Dariya’s work to illustrate the cover of Jorge Amado’s book, “Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands”:

— One day they wrote to me and asked to buy one of my vytynanky for a book cover. People rarely buy images like that for their homes — they order something easier to understand — lions or something. This image is of a woman with two men — it really suited the book.

Dariya expresses an interest in modern projects, but traditional and folk symbols are also deeply rooted in her work. Even when she is trying to create something abstract, Ukrainian symbols emerge.

— When foreigners started taking an interest in my work, they felt it was pervaded with Ukrainianness,” she recalls. “I was afraid that in France it would be seen as ‘sharovarshchyna’ (a derogatory term denoting a pseudo-folk representation of Ukrainian culture). But when I set up the Ukrainian stand at the Salon du livre (the annual Paris book fair), it was such a good fit that everyone agreed it was both contemporary and authentic.

Dariya has also made works for the Roman Ivanychuk library in Lviv, based on Ivanychuk’s novels:

— The first piece was based on his novel ‘Malvy’ (“Mallows”) and we decided to include an inscription from it. There are also a lot of intertwined symbols that are hard to make out. If you look closer, you can see little letters — the whole alphabet is intertwined here. At the top, you can see the Ukrainian trident and mallow flowers.

The second piece bears the library’s logotype – ‘The library on Market Square’. The third one has a quotation from Roman Ivanychuk: “In this land your umbilical cord is buried.”

— This vytynanka is based on his novel ‘Manuscript’: there’s a rolled-up manuscript and an orans (a figure in a posture of prayer, with hands outstretched sideways). In a way, it symbolises the unity of Ukraine.

Life-changing social networks

Dariya is used to sharing her work and even her creative process on Facebook. She posts as soon as she finishes a piece, which generates customers. Dariya admits that selling pre-made works is much easier than making specific images to order:

— When I create something, post it, and then people buy it, that’s the best outcome.

It is thanks to her active use of social media that Dariya has been able to find an audience for her work outside of Ukraine:

— It’s really cool that we have social media now. It’s just life-changing, in my opinion. All my journeys abroad began with Facebook — people saw my work and then wrote to invite me. When you’ve been abroad and come back to Ukraine, you’re already a star. Before that, nobody knew you. All you needed to do was go to Paris for three days.

Making vytynanyky for a living and dreaming of having her own workshop, Dariya hopes that one day, when her children grow up, she can return to working with stone. The children aren’t far behind their parents — each is looking for their own creative pathway, continuing the family’s artistic journey.