How does Russia’s war in Ukraine endanger the environment and what can we do to restore it? Let’s find out from Ostap Reshetylo, associate professor at Ivan Franko National University of Lviv and project manager at World Wildlife Fund (WWF)-Ukraine.

Ukraine is the largest country whose borders lie entirely in Europe. In Ukraine, as well as in the Black and Azov seas, a variety of landscape and climatic conditions have created habitats for around 50,000 species of animals.

slideshow

The gradual destruction of natural landscapes and the development of human-created and controlled ecosystems in their place have led to the extinction of many local species and to the emergence of allochthonous species — those that historically come from other areas, including crop pests. These processes have unfortunately accelerated in the 21st century, most notably since 2014, when Russia began its military invasion of Ukraine. The invasion has had devastating effects on Ukraine’s environment.

The impact of warfare on ecosystems

The impact of war on biodiversity and nature in general cannot be overstated. For example, in World War I, 9 million horses died, and the numerous trenches dug changed the landscape of Europe. In World War II, about 200,000 horses in the German army were killed in just two months. Russia’s armed aggression in Ukraine also harms the environment. It is important to discuss these consequences now so we can better manage them in the future.

Photo from open sources.

Since the start of the full-scale war in 2022, about 25% of Ukraine’s protected areas have been occupied. This includes about 900 protected sites, 14 of them wetlands of international importance. Some of the sites are part of the Emerald Network, a pan-European network of protected areas outside the EU created to protect endangered species and habitats. Fortunately, some of these areas have been liberated, but those in the east and south of Ukraine remain occupied.

Photo: Yurii Stefaniak.

War impacts the entire ecosystem. In addition to living creatures, soil, air, and water can also undergo damaging effects. For instance, if soil becomes imbalanced, everything that lives in and around it — from the smallest microorganisms to mammals — suffers as well.

When it comes to environmental pollution as a result of hostilities, soil must be examined. Many harmful substances can accumulate in soil, in particular due to explosions and missile attacks. Metal fragments can remain in the soil for a long time, and various chemicals can pollute it. This pollution lasts for years, if not decades.

Since water systems are self-cleaning, rivers and lakes generally accumulate less pollution than soil. Their complex systems of life, the flow of water, and the settlement of pollutants to the bottom help these bodies of water remain more resilient to pollution. However, they are not immune to it.

Photo: Yurii Stefaniak.

Fortunately, while the air is also polluted in certain areas, it is at the lowest level of concern. Since air pollution is localized and air masses are very mobile, the concentration of harmful substances gets carried away and disperses, settles, and diminishes.

This is not to say that the air is completely safe, though.Polluted air can cause acid rain that damages plants and soil. And as the most passive part of the environment, the soil will accumulate most of the pollutants.

The full scale of the environmental consequences of the war can only be known after it’s over. Prohibitions on visiting certain areas, whether due to active hostilities or mines, make it impossible to study the environment holistically. But by evaluating what is currently known about the war’s damaging environmental effects, we may be able to better prepare for future restoration.

How Russia is harming animals

Different animals are affected by the war in different ways. Those that are more mobile, easily startled, and have better developed self-preservation instincts — such as bears, wolves, lynx, deer, and elk — are less directly affected by the war. They are rarely seen in peacetime, and even less so in regions with active warfare. The sound of explosions scares them, so when they have the opportunity, they run away from them.

There have unfortunately been cases of deer and other large animals being killed by mines or tripwires in mined areas, but in most cases, these are isolated incidents.

Photo: Yurii Stefaniak.

However, most other animals get disoriented and frightened by explosions, shooting, machinery, night flashes. This forces them to change their behaviour and their usual life cycles, which can affect a population’s future. For example, if a forest burns down or a body of water becomes so polluted that animals cannot live there, they are forced to look for a new suitable environment. If there are no suitable areas nearby, they may face a lack of food, which can lead to the death of part of the population.

While it may seem easy for birds to change habitats — they can fly, after all — it’s not that simple. Birds’ flight and migration patterns are well-established with clearly defined routes and timelines. The war has disturbed these patterns, brought the threat of death and caused a lack of safe places to rest, feed, and nest. In Ukraine’s forests, for example, the “period of silence” — when animals typically breed and humans are prohibited from disturbing them — lasts from April to June. Imagine that during this period, everything around these forest animals explodes and burns. How is their natural breeding impacted? Certain species will have fewer or no newborns, which will affect current and future population dynamics.

It is still too early to say whether the war has changed birds’ migration routes because these creatures have highly developed instincts to return to the same places or to an area close to their usual habitat. Storks, for instance, try to return to the same area or even to the same nest. For now, birds’ migration routes and habitats in Ukraine remain relatively stable, but the longer the war lasts, the more likely their behaviour will change. This could lead to a disproportionate amount of deaths or the failure to reproduce.

Photo: Yurii Stefaniak.

Animals that are lower on the evolutionary tree, may die more often from the effects of the war because they are less mobile and cannot escape as far as birds or larger animals. However, these animals are less sensitive to flashes and sounds. If their habitat does not have active hostilities, they won’t be directly affected.

Which species are endangered in Ukraine

The most threatened animals are the endangered species that live in the steppe zone, where most of the war’s destruction has occurred. From eagles to bison, these animal populations are facing grave threats due to Russia’s hostilities.

The steppe eagle is a bird of prey that occasionally appears in the Azov-Black Sea region during migration. It is listed as “endangered” in the Red Book of Ukraine, the official list of threatened species in the country. One of the last nesting sites of this species was recorded in Askania Nova, a protected area in the Ukrainian steppe that has been occupied by Russian troops since the beginning of the full-scale war.

Photo: Serhii Korovainyi.

The marbled polecat, a small predator of the Mustelidae family, is listed as “vulnerable” in the Red Book of Ukraine. Only about 100 of them remain in the country. Marbled polecats prefer steppe areas and sometimes live around shrubs and river valleys in Donetsk and southern Slobozhanshchyna. Today, these habitats are being destroyed by hostilities.

The steppe marmot, a rodent known as a harbinger of spring, feeds on steppe vegetation. Its main populations in Ukraine are found in the Slobozhanshchyna and Donetsk regions. In 2021, the steppe marmot was listed in the Red Book of Ukraine and was recognized immediately as “endangered”. The population has reached a critical point due to active hunting, habitat destruction and fragmentation, and now active warfare.

The bison of the Zalissia and Konotop subpopulations, which are also in the Red Book of Ukraine, had their territories invaded by Russian troops in the first days of the full-scale war. Even though the Russian occupation of these territories lasted only about a month, it affected the number and general condition of the bison. The southern area of Zalissia National Park became an arena for hostilities, along with surrounding villages. The park was subjected to powerful artillery and mortar shelling. Military units and equipment travelled along forest roads. Large areas of the park were mined, which still poses a problem for the safety of people and animals in these areas. The bison of Zalissia also lost the males in their population due to the war, which means that the herd is infertile. If no bulls are introduced in the near future, this subpopulation will be doomed to extinction.

Photo: Rafał Kowalczyk.

Although there were no active hostilities in the Konotop forest, the roar and noise of military equipment was stressful for animals. This included the local bison, which left their usual habitats and moved deeper into the forest. When they returned to their regular feeding areas almost a year later, scientists discovered that no new bison had been born that year. This is likely due to the stress caused by Russian troops’ interference in their environment.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine also caused the suspension of a project to restore the bison population in the Chornobyl exclusion zone. Developed by the European Bison Friends Society and financially supported by the World Wildlife Fund, the project aimed to create a new population by transporting a herd of nine bison from Poland. A four-hectare enclosure in the Chornobyl zone was specially built to house the animals before their release into the wild. Just when the transport phase of the project was finalized and almost ready for implementation, Russia launched its full-scale war. The transportation of the bison was suspended. However, even though these territories were temporarily occupied, the enclosure remains intact. The WWF-Ukraine team believes that the bison reintroduction project can be relaunched after Ukraine wins the war and the territory is completely demined.

Bison, Kivertsi National Park, Tsuman Forest. Photo provided by the authors.

What can help animals in Ukraine

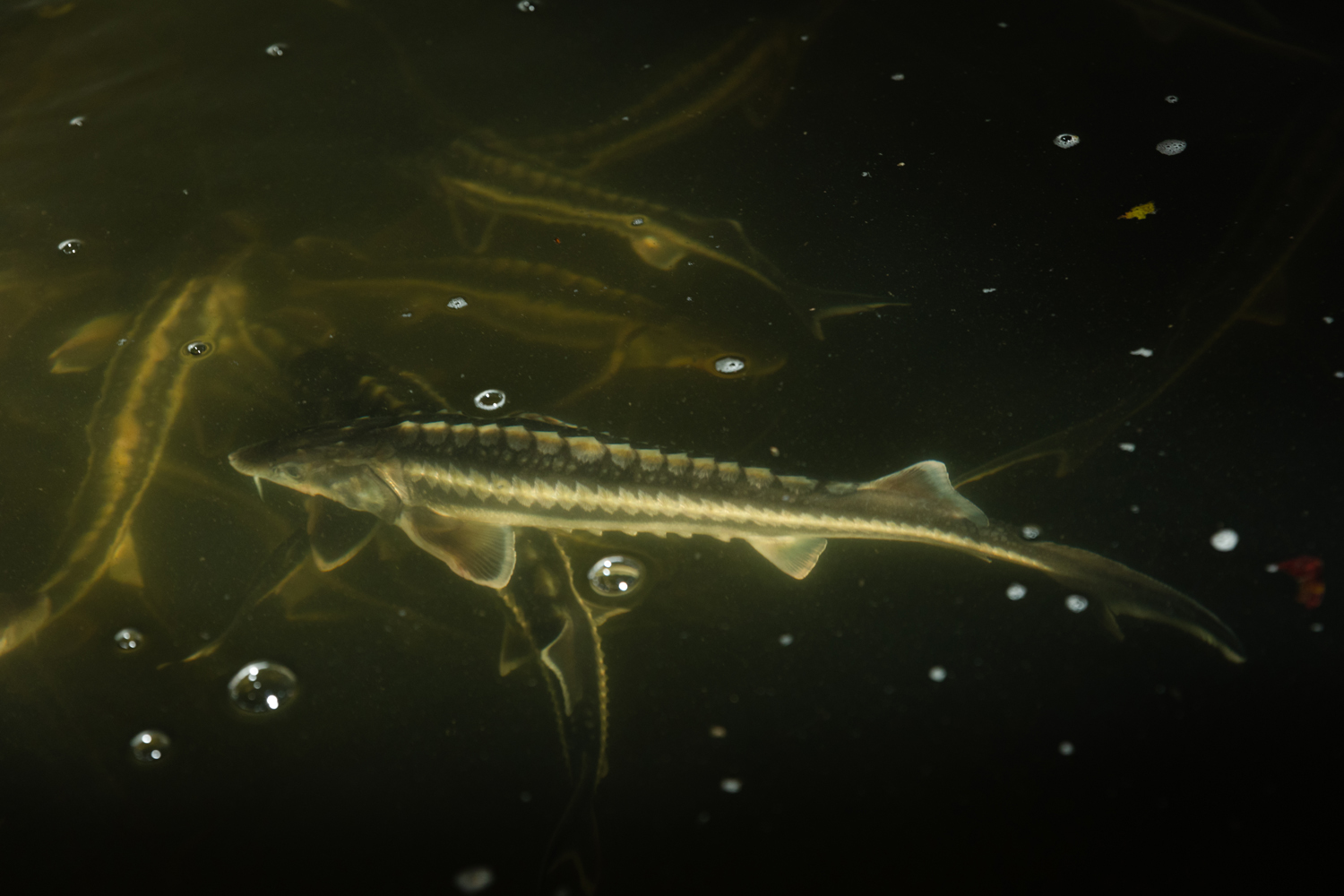

Aquatic ecosystems are suffering from the environmental effects of Russia’s military invasion too. Russian troops’ destruction of the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant triggered an environmental and humanitarian disaster and threatened the existence of many species, including sturgeons. Sturgeons are an “umbrella species”, meaning that their conservation supports other species and the sustainability of ecosystems in general. Today, all species of sturgeon found in Ukrainian waters are listed as endangered or vulnerable. The deterioration of conditions needed for reproduction and the impact of illegal fishing have led to a significant decline in population numbers and the sturgeon’s inclusion in the Red Book of Ukraine. Effects of the Russians’ destruction of the power plant further worsened the conditions needed for a healthy sturgeon population.

Stocking the Danube with sturgeon. Photo provided by the author.

On 18 October 2023, the WWF-Ukraine team released 2,500 young sterlet and diamond sturgeon into the Danube River. Called stocking, this process is not only about nature conservation. It also supports a long-term strategic goal to help restore the sturgeon populations in the Danube and ensure the monitoring and protection of their habitats. The Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine is also working on establishing aquaculture sturgeon farms to provide fishermen with an alternative source of income and to combat the poaching of sturgeon for black caviar, which is the main reason for their critically endangered status. This is one mechanism of environmental restoration in Ukraine and a powerful step towards increasing the Danube sturgeon population and biodiversity as a whole.

Stocking the Danube with sturgeon. Photo provided by the author.

Nature takes time to recover. A tree can be destroyed in an instant, but how long does it take to grow back? This is also true for other components of natural systems, particularly population size. The key question is: when will rare species be able to recover, and will they be able to recover at all?

Photo: Yurii Stefaniak

Ukraine has many rare steppe species whose habitats are small and concentrated mainly in the southeastern part of Ukraine, where the most intense hostilities are taking place. Some live in parts of Donetsk and Crimea that have been occupied for almost ten years. We still don’t know what is happening to the populations of rare reptiles, predators, and marine invertebrates there. When the war is over, research will certainly be conducted, but the results may shock us. How can all of this be restored? It will take time and a lot of resources. We must also be prepared for the possibility of losing something and being unable to restore it to its pre-war form. If this happens, we will have to rethink how to best focus our environmental restoration work in Ukraine.