Throughout history, we have seen many international trials of war criminals who felt absolute impunity before that. After unleashing an unprovoked full-scale war against Ukraine, Russian president Putin has become the main war criminal that must face an international tribunal. There is a lot of debate about what exactly that should look like.

On 3 April 2022, President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelenskyy announced the creation of a special judicial mechanism to investigate Russian war crimes. On 25 May, the US Department of State announced the establishment of an Atrocity Crimes Advisory Group (ACA) to prosecute those involved in war crimes during Russia’s war against Ukraine. It is clear that the criminal prosecution of Putin and his henchmen by international justice is inevitable. In this material, we provide examples of international trials of war criminals that took place in the past or are taking place now.

The first attempts to convict war criminals took place after World War I. The Leipzig trials of 1921 of German war criminals and the prosecution of Ottoman war criminals (the latter committed genocide against Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians) were unsuccessful attempts and turned into a farce due to political pressure. Of the 901 accused of war crimes at the Leipzig trials, 888 were acquitted. The rest were sentenced to short prison terms, and some escaped from prison. The trial of Ottoman war criminals was supposed to take place in Malta, but this did not happen due to the lack of a legal framework and political will. Perhaps it was the lack of punishment for the war criminals of World War I that led to the horrors of the second and largest world war to date.

Subsequent international trials of war criminals, which took place after World War II, were more effective. In this text, we describe the background of each such trial, the personalities of the accused, their charges and sentences.

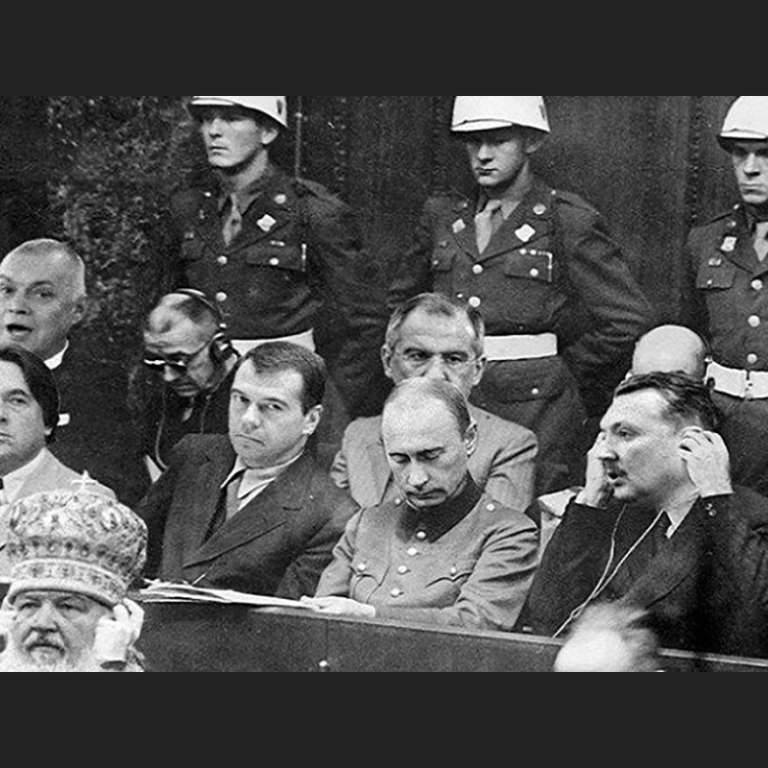

Nuremberg trials (1945–1946)

Background: The International Military Tribunal, better known as the Nuremberg trials, was the first successful international trial of war criminals. It was established by a coalition of the victorious states in World War II: the USA, Great Britain, France, and the USSR. Representatives of these states created the Charter of the International Military Tribunal. The major war criminals of Nazi Germany were tried on its basis. The place of the tribunal was not defined arbitrarily because it was in Nuremberg that the congresses of the Nazi Party took place.

Accused: 24 leaders of Nazi Germany, including Reichsmarschall Goering, Hitler’s deputy as the National Socialist party leader Hess, Foreign Minister Ribbentrop, head of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht Keitel, as well as party functionaries, ministers, leaders of occupied territories, and propagandists. Even before the start of the trial, one of the accused committed suicide by hanging himself from a sewer pipe in prison. Another was recognised as terminally ill and was not tried.

Charges: The defendants were charged with crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. During the Nuremberg trials, the prosecution used the newly invented term ‘genocide’ for the first time in history, although the defendants were not tried for this particular crime.

Genocide

Intentional actions aimed at the complete or partial destruction of population groups or peoples based on national, ethnic, or racial features.Verdict: 12 defendants were sentenced to death (one in absentia), 7 were sentenced to various terms of imprisonment, and 3 were acquitted. The Nuremberg tribunal was not an independent judicial body because it was a court of the winners against the defeated. It did not provide for a pre-trial investigation, and the defendants were named criminals in the primary indictment documents. Only their punishment was chosen at the trial. However, the detailed analysis of the crimes of the leaders of Nazi Germany in an open trial had historical and symbolic significance.

Tokyo trials (1946–1948)

Background: The International Military Tribunal for the Far East, held in Tokyo, aimed to convict war criminals of Japan, Germany’s World War II ally. The tribunal included representatives of 11 victorious countries in World War II: Australia, Great Britain, India, Canada, China, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the USSR, the USA, the Philippines, and France.

Accused: 29 military and political leaders of the Japanese Empire, including prime minister and de facto leader of Japan Tojo Hideki. Emperor Hirohito managed to avoid the tribunal because of his symbolic importance to Japan and his agreement to surrender. Even before the start of the trial, one of the accused committed suicide, and the propagandist Shumei Okawa was recognised not criminally responsible by reason of mental disorder.

Charges: Like the German leaders, the Japanese defendants were charged with crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.

Verdict: 7 defendants were sentenced to death, 18 were sentenced to various terms of imprisonment, and 2 defendants died during the trial. Like the Nuremberg tribunal, the Tokyo tribunal was a trial of the winners against the defeated. It also did not provide for a pre-trial investigation, because the Japanese military leadership was recognised as war criminals according to the Potsdam Declaration of 1945. After the Tokyo trials, there has not been a single case of conviction for crimes against peace (now called crimes of aggression). This can soon be an indictment against Putin and his henchmen.

Crime of aggression

The use of armed forces by a state against the sovereignty, territorial integrity, or political independence of another state (as defined by the UN).

International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (1993–2017)

Background: International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia was established in 1993 by a resolution of the UN Security Council to investigate crimes committed during the wars in the former Yugoslavia over 1991─2001. Unlike the previously described ones, this trial can be considered impartial because it took place on neutral territory (in The Hague, the Netherlands), and judges were appointed by the UN General Assembly. The tribunal selected the more humane life imprisonment as the harshest punishment. For the first time, the tribunal introduced the principle of command (hierarchical) responsibility, recognising the superiors’ guilt for the crimes of their subordinates.

Source: Getty Images.

Accused: 161 people, including the former president of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Slobodan Milošević, the president of the self-proclaimed Republika Srpska Radovan Karadžić, the commander of the army of the self-proclaimed Republika Srpska Ratko Mladić, and other military and political leaders of the former Yugoslavia.

Charges: The tribunal investigated war crimes and crimes against humanity, and for the first time in history, brought charges for acts of genocide, namely crimes against Bosnian Muslims committed in Srebrenica (a city in eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina) in 1995. The tribunal relied on the provisions of the Geneva Conventions adopted in 1949.

Source: Getty Images.

Verdict: 90 defendants were found guilty and sentenced. 21 were acquitted. 13 cases were transferred to national courts, and 37 were dropped due to the withdrawal of charges or the death of the accused. Slobodan Milošević died in The Hague prison in 2006, never having heard the tribunal’s verdict. In 2016, Radovan Karadžić was sentenced to 40 years in prison (later, an appeal revised the ruling in favour of life imprisonment) for war crimes and the genocide of Bosniaks. In 2017, Ratko Mladić was sentenced to life imprisonment for the genocide in Srebrenica and the shelling of Sarajevo. In 2017, one of the defendants, former Bosnian Croat general Slobodan Praljak, took poison right during the announcement of the verdict and died shortly after.

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (1994–2016)

Background: The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda was created based on UN Security Council resolutions to prosecute those responsible for violations of international humanitarian law in Rwanda and neighbouring countries. It is primarily about the genocide of the Tutsi, an ethnic people of Rwanda, committed by members of the Hutu ethnic majority in 1994. The tribunal operated in Arusha, Tanzania, and the appeals chamber was located in The Hague.

Accused: Rwanda’s military and political leadership, including former prime minister Jean Kambanda, as well as politicians, businessmen, members of religious groups, and directors of mass media. A total of 96 were accused.

Charges: The tribunal had jurisdiction over genocide, crimes against humanity, and violations of the Geneva Convention.

Verdict: 61 defendants were sentenced to various prison terms, 14 were acquitted, and 10 cases were transferred to national courts. Regarding 8 defendants, the proceedings were discontinued, in some cases, due to death. 2 accused are still wanted, and 1 was caught only in 2020.

Source: Getty Images.

The Rwandan tribunal is particularly interesting because within this prosecution, propagandists were found guilty of inciting genocide. It was the first time since the Nuremberg trials that hate speech was recognised as a war crime. Ferdinand Nahimana, the director of the radio station Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM), was sentenced by the tribunal to life imprisonment (after an appeal — to 30 years in prison). The executive director of RTLM, Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza – to 35 years (after an appeal – to 32 years). The editor-in-chief of Kangura newspaper, Hassan Ngeze – to life imprisonment (after an appeal – to 35 years). The correspondents Bernard Mukingo and Valérie Bemeriki – to life imprisonment. The organisation Reporters Without Borders, which takes care of the freedom of the press and the rights of journalists, approved this decision. RTLM conducted hate speech broadcasts against the Tutsis for only one year, while the state propaganda of the Russian Federation has been creating an alternative information reality for decades.

Special Court for Sierra Leone (2002–2013)

Background: The Special Court for Sierra Leone was established in 2002 to investigate particularly serious crimes committed during the 1991-2002 war in Sierra Leone between the government and the Revolutionary United Front (RUF). About 120,000 people died during almost 11 years of war. The court was established by an international agreement between the government of Sierra Leone and the United Nations. The Special Court operated in the country’s capital, Freetown.

Accused: 23 people, including the former president of Liberia, Charles Taylor, who supported the RUF, which was distinguished by particular cruelty and recruiting children in the war; Foday Sankoh, the leader of the RUF; Johnny Paul Koroma,the self-proclaimed president of Sierra Leone.

Charges: Crimes against humanity, violations of the Geneva Conventions, international humanitarian law, and laws of Sierra Leone.

Verdict: 16 people received prison sentences, including Charles Taylor, who was sentenced to 50 years in prison in 2012 for crimes against humanity and war crimes. Three people were acquitted, three more died during the trial, including Foday Sankoh, who died in 2003. One accused, Johnny Paul Koroma, fled and has not been found.

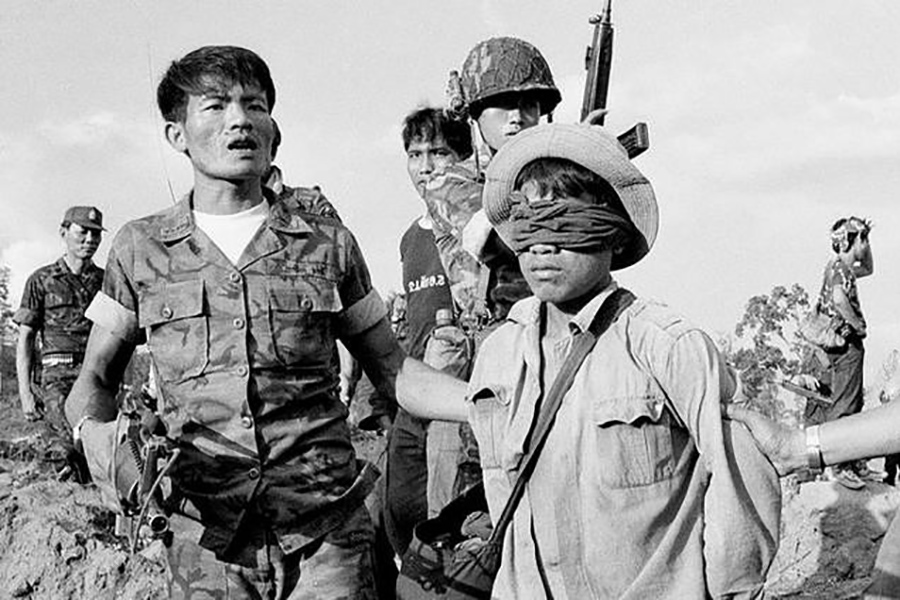

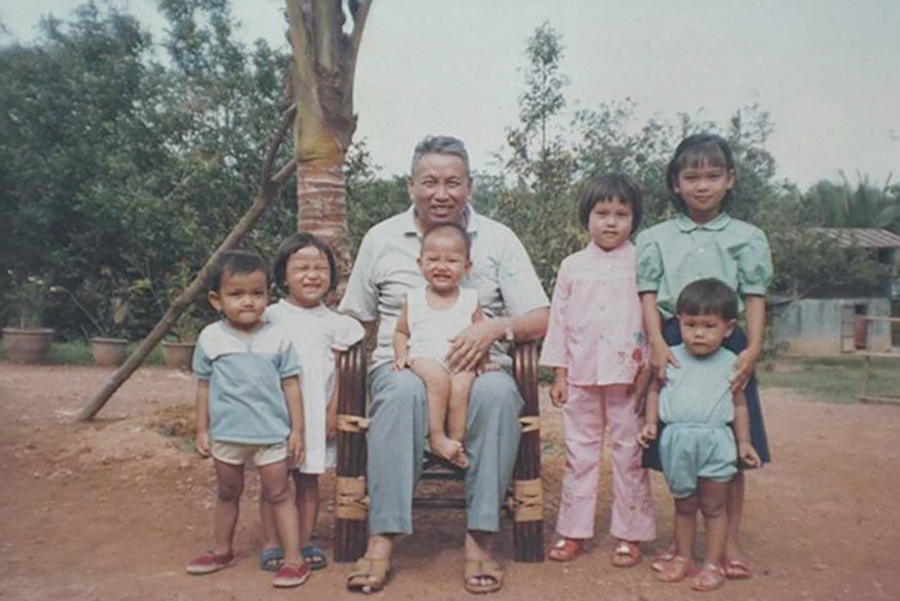

Khmer Rouge Tribunal (2003–present)

Background: The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), or the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, was created to prosecute the leaders of the Khmer Rouge, the radical communists who seized power in Cambodia in 1975. They proclaimed the so-called Democratic Kampuchea, also known as the Genocidal Regime, which lasted until 1979 and killed between 1 and 3 million people. The Cambodian government established the tribunal in cooperation with the United Nations. Meetings are held in Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia. The most notorious leader of the Khmer Rouge, Pol Pot, died in 1998, even before the start of the tribunal.

Accused: 9 leaders of Democratic Kampuchea, including Pol Pot’s closest associates: Kaing Guek Eav, Nuon Chea, Khieu Samphan and others.

Charges: Genocide of Vietnamese and Cham people living in the territory of Cambodia, crimes against humanity, war crimes, as well as crimes under the Criminal Code of Cambodia.

Verdict: Kaing Guek Eav, Nuon Chea, and Khieu Samphan received life sentences. One defendant died before the verdict. Another defendant was found not criminally responsible by reason of Alzheimer’s disease. Cases against another 4 were closed. The EССС was the first trial of a communist regime, but unlike the Nuremberg trials against Nazis, which is often criticised for its lack of objectivity because winners judged the defeated, the trial of the Khmer Rouge is considered neutral and impartial.

Special Tribunal for East Timor (2000–2006)

Background: The Special Panels for Serious Crimes were established by the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor to prosecute perpetrators of serious criminal offences committed during East Timor’s struggle for independence from Indonesia in 1999. The Special Panels were established by the UN administration unilaterally, that is, not based on an international agreement between the UN and East Timor since the country was under the temporary administration of the UN. Moreover, East Timor had no criminal law or judicial system to investigate serious crimes. The Special Panels were held in the city of Dili, the capital of East Timor.

Accused: Almost 400 people were indicted. However, only 88 accused appeared before the court. The rest were citizens of Indonesia whose government refused to hand them over to East Timor or the UN.

Charges: Genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, murder, sexual crimes, torture.

Verdict: 84 people were convicted and 4 were acquitted.

Special Tribunal for Lebanon (2009–present)

Background: The Special Tribunal for Lebanon was established in 2007 to identify and prosecute those responsible for the 2005 assassination of former Lebanese prime minister Rafic al-Hariri and 21 others. This was the first international tribunal that prosecuted persons guilty of acts of terrorism. The tribunal was established by the UN together with the government of Lebanon and has been held in the Dutch city of Leidschendam since 2009.

Accused: 4 people associated with the Shia organisation Hezbollah, recognised by many countries as a terrorist organisation.

Charges: Prior conspiracy and commission of an act of terrorism using an explosive device, intentional homicide with the deliberate use of explosive materials, and attempted intentional homicide.

Verdict: In 2020, Salim Jamil Ayyash, linked to Hezbollah, was sentenced in absentia to five life terms in prison. Three other defendants were acquitted.

Kosovo Specialist Chambers (2015–present)

Background: The Kosovo Specialist Chambers and Specialist Prosecutor’s Office were established to prosecute former members of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) who were involved in war crimes during the 1998–2000 Kosovo War. The Specialist Chamber was created by the Republic of Kosovo together with the EU. Although it is part of Kosovo’s judicial system, the Specialist Chamber is completely independent of any national courts in Kosovo. It has the right to first try all criminal cases within its jurisdiction. The court is located in The Hague.

Accused: 8 people, including the former commander of the KLA Salih Mustafa, as well as Hashim Thaçi, who was the president of Kosovo at the time of the indictment.

Charges: War crimes, crimes against humanity.

Verdict: The trial for three people began in the fall of 2021. As for the rest of the accused, the pre-trial investigation is ongoing.

International Criminal Court

Background: The International Criminal Court (ICC), based in The Hague, is the only international organisation that operates permanently and prosecutes those responsible for genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and crimes of aggression. It was created in 1998 based on the Rome Statute, which, as of 2022, was ratified by 123 countries of the world (Russia first signed it but then withdrew). The ICC can investigate crimes committed on the territory of countries that have ratified the Rome Statute or signed a special agreement with the ICC (as Ukraine did after the Revolution of Dignity and the beginning of the Russian-Ukrainian war). The court’s jurisdiction is limited only to crimes committed after the Rome Statute came into force (2002).

fter the full-scale invasion of Russian troops into Ukraine, 39 countries appealed to the ICC regarding the situation in Ukraine. On 2 March 2022, the ICC began investigating war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in connection with the Russian Federation’s aggressive war against Ukraine. ICC prosecutor Karim Khan has already visited Ukraine several times, where he collected evidence of crimes committed by the Russian military.

Accused: Since its inception and as of 2022, the International Criminal Court has indicted 46 individuals. Among the defendants are the former president of Sudan, Omar al-Bashir, the former president of Côte d’Ivoire, Laurent Gbagbo, and the son of Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi.

Photo: The New York Times.

Charges: Genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and crimes of aggression.

Verdict: 8 people were imprisoned, 4 were acquitted, 10 had their charges dismissed or withdrawn, 4 died before the trial began. As for the remaining 20 people, the proceedings are ongoing. Malian Islamist Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, convicted by the ICC in 2016, was sentenced to 9 years in prison for ”intentionally directing attacks against religious and historic buildings”, which is a valuable precedent for Ukraine.

Given the previous experience of international courts on war criminals, it can be predicted that for the war in Ukraine, the military and political leadership of the Russian Federation will be charged with crimes against humanity, war crimes, crimes of aggression, and possibly genocide, which is much more difficult to prove than others. Crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide can be investigated at the ICC in The Hague.

However, the ICC will not be able to investigate the crime of aggression, since neither Russia nor Ukraine has ratified the Rome Statute. Therefore, a separate temporary judicial body, a tribunal, will be created to investigate the crime of aggression. Ukrainian and international lawyers are already working on creating such a tribunal. At the same time, the trials of the direct perpetrators of war crimes are taking place in Ukrainian courts. Thus, on 23 May the Solomianskyi District Court of Kyiv sentenced Russian sergeant Vadim Shishimarin to life imprisonment for the murder of a Ukrainian civilian.

International courts that have tried or are trying war criminals are criticised for many reasons. Primarily, for the duration of trials. In some places, trials drag on for many years, and the accused often do not live to receive their sentences. However, international trials of war criminals have historical significance because they shed light on historical events and the role of high-ranking officials in crimes. These courts are the only ones capable of providing adequate punishment for international criminals within the civilised legal field. However, it is worth noting that most of the listed international trials became possible only after the military victory over the criminals. Therefore, Ukraine must defeat the enemy on the battlefield before it gets a chance to bring the war criminals to justice.