In 2020, London celebrated the 15th anniversary of the Plast revival. Created in a similar way to scouting but with national features, for many people, this youth movement is an important place for growing up and education, shaping one’s identity, and acquiring important skills and abilities. Plast centres among emigres, including the branch in London, allow local youth to keep in touch with Ukraine, as well as to present Ukraine to the world.

In the middle of the 20th century, Ukrainian Scouting known as the Plast movement spread abroad in various countries around the world, including Great Britain. Today, in London alone, there are more than 100 active members, and the organisation itself serves as one of the cultural centres around which the Ukrainian diaspora unites.

Who are the plastuny?

Scouting is a voluntary non-political youth movement that operates in most countries of the world. It is designed to promote the physical and intellectual development of all children involved, regardless of affiliation; to form emotionally and spiritually mature individuals; to educate socially responsible citizens of local, national, and international communities.

The first Scout camp was held in England in 1907. Its founder was a British military officer and writer Robert Baden-Powell. Four years later, on the initiative of three teachers, Oleksandr Tysovskyi, Ivan Chmola, and Petro Franko, a similar organisation was founded in Lviv, that was a part of Austria-Hungary at that time. The creators of the Ukrainian Scout movement have developed their own educational system, similar to the Scout one but with some differences. The newly created organisation was named Plast. In addition to the English term ‘scouting’, the founders came up with their own, ‘plastuvannia’, derived from the name of the Cossack scouts who moved around crawling to remain unnoticed.

Plast uses non-formal education methods with an emphasis on practical outdoor activities. Summer camps and activities in nature have been an integral part of Plast since the very beginning because such a setting allows one to test strength and acquired knowledge the best. Nowadays, there are Scout camps of various directions: art, recreation, horse-riding, aquatic, etc. where Plast members champion their skills.

Vmilist

(Ukr. for ‘ability’) It is a confirmation of knowledge and skills provided within a certain Plast activity (for example, ‘ship science’, ‘horseback riding’, ‘cartography’). The ability merit badge is sewn onto a uniform.

Today, Plast is administratively divided into okruhy (‘districts’), stanytsi (or mistsevosti; ‘branches’ or ‘zones’), and kureni (‘huts’). Groups of up to 30 people gather in kureni to work together. The symbol of the organisation is a lily woven into the Ukrainian trident, and its petals stand for the three main responsibilities: to be faithful to God and Ukraine, to help others, and to live by the Plast law. Another well-known attribute is the scout uniform that covers up all the differences in social status and ensures the equality of all the organisation members.

Plast branches operate in most regions of Ukraine, as well as abroad: in Germany, Poland, Canada, the United States, Australia, Argentina, and other countries where there is an active Ukrainian community. The main goal of the organisation is to promote the patriotic education of conscious Ukrainian youth.

Today, the Plast members (Ukr. ‘plastuny’) from Great Britain have the opportunity to go to Scout camps in neighbouring countries, such as Germany, where they can try other activities and expand their outlook. They also go to camps in Ukraine to see the local Plast, to feel the spirit of camping in the Carpathians, and to meet their peers.

Special features of the British Plast. Marta Muliak

Today, one of Plast’s powerful centres among emigres is the Ukrainian Scout Organisation in Great Britain. After the end of the Second World War, those who could not return to their homeland or stay there began to come here en masse from Europe. Most of them were divisional soldiers and people connected with the Ukrainian underground or released from labour camps.

During 1946–1947, the first national groups were established, and the following year the first congress of the Plast members took place. Later, Ukrainian scouting centres appeared in Manchester, London, Derby, Nottingham, and other cities in Great Britain. The Plast branch in London was founded on February 25, 1950, thanks to the efforts of M. Levytskyi. In 1970, Marta Enkala founded a senior Plast group, and in 1979, she was elected the head of the London branch. Together with her brother Adrian, they were engaged in the Plast movement since they were teenagers.

However, later Plast in Britain began to decline. Until the ‘60s of the 20th century, the organisation operated only in some small centres. The Kraiova Plastova Starshyna (Ukr. ‘National Plast Office’) was concentrated around Manchester and actively organised the annual summer camps at the Verkhovyna Plast Home in Wales. The large-scale Plast revival began in 2005, with the first meeting in London, says the current mentor and head of the London branch, Marta Muliak.

Vykhovnyky

(Ukr. ‘mentors’) Older Plast members who help young people join the movement.“The revival of the Plast branch in London began with three families who came to England from different countries: the family of Orysia Martsiuk who was born in Germany, the Shyshko family from America, and the Grabovych family from Canada. They gathered and initiated the first meetings. ‘I flew to London in 2006, on January 7, when Koliada was just beginning. I went to this Koliada celebration and stayed with these 3 families to develop Plast.”

A couple, Oksana Litynska and Denys Uhryn, also joined the activities of the revived Plast. Both were engaged in the Plast movement in Ukraine back in the 90s and met each other in the organisation. In Ukraine, Denys took part in launching many sports camps, in particular, he was the founder of the ‘Fest’ ski camp. Oksana manages to combine the position of CFO in a London bank and work responsibilities at Plast. Since March 2021, she has headed the Kraiova Plastova Starshyna, overseeing the development of Plast throughout the UK. In addition, Oksana and Denys are mentors at the London branch. Both are fond of mountaineering and hiking, in particular, since 2013 they have climbed to the highest peaks of each continent. They also organise trips for children from Plast.

Kraiova Plastova Starshyna, KPS

(Ukr. ‘National Plast Office’) Executive and administrative body of Plast.In England, Marta Muliak has been working for the National Health Service for over 10 years, planning palliative care for critically ill patients. At the same time, she has always been an active Plast member. She first joined the organisation during her school years, having met a girl from Plast during an ethnographic expedition of the Lviv Junior Academy of Sciences.

Marta remembers well her activity in the Ukrainian Plast and believes that partly thanks to it she managed to establish herself personally, acquiring important skills and abilities. In particular, she often recalls the story when as a mentor, she went camping with younger children.

“There were three of us mentors, aged 19. We took 30 girls to the mountains. And suddenly one child said: ‘My heart hurts’ and started choking. We grabbed this child in our arms, left one mentor with the group, and hurried to the camp ourselves. We ran there, called an ambulance and the child’s parents. Fortunately, everything was fine after the child had had some rest. But this situation has shown that sometimes we work with children on the verge of danger. This requires constant attention and responsibility from mentors.”

slideshow

Nowadays, her responsibilities as head of the branch include keeping the entire team of the branch together, supporting members if necessary, taking care of financial affairs, cooperating with state and public organisations, in particular with other scouts. By the way, any activity in Plast is carried out voluntarily.

Marta says that you can join the organisation from an early age. Children from three to six years old come to Plast: they are ‘Plast little birds’ that have a separate educational program. At the age of six, there is a transition to the level of novice Plast members. From the age of eleven to eighteen, children engage in Plast activities within an ulada (Ukr. ‘community’) of youth. Those who decide to stay in the organisation as mentors move to the ulada of senior Plast members (18-35 years). After 35 years, the seniorship ulada begins and its duration is not limited. People of all ages can join Plast. Often parents join in the process of their childrens’ Plast activities. The main requirement is to pass the test, take the Plast oath, and continue to live by the rules.

“The Plast law consists of 14 points that list the characteristics that a plastun must have. For me personally, one of the most important is to ‘always be cheerful’. That is, no matter what obstacles may come your way or the people you interact with, always stay positive and think of everyone as best you can. In fact, it is a big challenge for people.”

Photo archive of Marta Muliak.

Marta says that Plast in emigration has three main tasks that resonate with her worldview and motivate her to remain active within the organisation: transmitting and preserving Ukrainianness abroad, communicating with nature, and educating confident, free, and responsible Ukrainian youth. According to her, today’s main goal of Plast is to provide such conditions that every child has the opportunity to join:

“In Plast, a person can develop or, as we say, self-educate; create your identity which is very important. It doesn’t matter if you are involved all the time or not. It happens often that Plast members officially leave the organisation, have a break for 5-6 years, and then come back. Once a Plast member, always a Plast member.”

The woman claims that Plast activities help not only to preserve the tradition, but also self realization through it, to set value priorities, to share what one has acquired with one’s children and, finally, with everyone who needs it.

“I am a part of Ukraine, and I do not associate Ukraine exclusively with its territory. Ukraine is in my genes, and I can’t imagine Ukraine without its language, tradition, history, and ornaments. I also can’t imagine not passing all these things to the next generation.”

Nourishing self-identity. Olha Mukha

Ukrainian Plast in the diaspora is significantly different from British scouting, says Olha Mukha, a youth ulada mentor at the Shark club. In particular, the education of local Scouts does not have such a powerful nationalist and cultural component, and outdoor activities are usually less intense.

“We (Plast in the diaspora — ed.) should always keep a balance between bringing some serious things and bringing some games so that it is pleasant for our members. We try to introduce a competitive aspect that allows us to include national education, cultural identity, knowledge of history, and the memory of the native land. We bring up healthy children with a full outlook and self-identification.”

Olha works as a manager for Congresses, committees, and new centres at the Secretariat of the International Organization for Writers and Journalists of PEN International. She combines her work with activities in Plast, where, in addition to education, she acts as a spokeswoman for the region of Great Britain.

The local Plast branch offers a lot of activities as the organisation cooperates with many other Ukrainian institutions in London, including the Ukrainian Social Club, the Union of Ukrainian Youth commonly referred to as CYM (Ukr. ‘Spilka Ukrainskoi Molodi’), and the Association of Ukrainians in Great Britain (AUGB), etc. In London, near Holland Park, a kind of national district has emerged where the Saint Sophia Society is located as well as the Ukrainian Institute of London, the Ukrainian Embassy, the main office and department of the CYM, and the offices of other organisations. There are even Ukrainian pubs with national dishes on the menu.

Most of the events are in one way or another focused around the Ukrainian House organised by the SUB. Here Plast members hold their charity fairs and thematic events, the Ukrainian Saturday school operates, CYM meetings take place, and young people gather in hobby groups: singing, dancing, and more. Plast’s main goal is to organise all of this as a great and exciting game, completely different from the concept of schooling, says Olha.

“We often say that all children have two days off, and our children have one at best because Saturday is always fully packed with various activities: Ukrainian school, Plast, and various parties.”

They try to involve students in a variety of activities, including those that add awareness of the connection with Ukraine and its past. For example, Plast members regularly visit the Hannersberg Cemetery where there are many burials of Ukrainian emigrants of various waves. Children participate in the restoration and arrangement of forgotten graves, thus studying certain parts of their history.

It is important not to just keep children busy with something but to keep them in the community through fascinating events. Therefore, at the beginning and end of the Plast year, the organisers arrange entertainment such as climbing, rowing, or kayaking, says the volunteer.

The Plast year

The period of the main functioning of the branch lasts from September to June, which includes every Saturday meetings, celebrations, and Plast meetings.Significant events in the life of the members such as admission to the Plast ranks or the transition to a new ulada are also accompanied by various rituals. Thus, during the action, the mentor greets the entrants with a left-hand shake and raising three fingers of the right hand (traditional Plast greeting), and then rewards them with honours that must then be sewn on the uniform. At the end of the greeting, all present shout ‘SKOB’ three times in honour of the new person. This is a Ukrainian acronym for the personal features that a Plast member should have: strong, good-looking, careful, and fast.

“We need something inspiring to make children want to be in society, supporting this format of play. Preserving the Ukrainian context is very important for us. We try to do this in such a way that children like it and want more.”

Olрa herself came to Plast when she was school age and lived in Lviv. For her, this was a great contrast to the Soviet school: training a sense of responsibility, self-testing, and getting out of the comfort zone.

“This is always a moment of internal competition. When you are primarily responsible for others. Accordingly, they are involved in such activities from the age of 15-16, when you understand what personal and collective responsibility is and how you can help solve problems.”

The woman claims that many of the skills acquired during the Plast membership helped her in later life and professional activities. In particular, they cultivated a sense of healthy leadership, self-sufficiency, and understanding of other collectives and cultures. She still clearly remembers the moment of taking the Plast oath.

“When I was 14 years old, we had a camp in Ternopil region. One night we were all alert in full uniform. And in the dark, we went somewhere with our senior colleagues, with torches, sometimes knee-deep in the water. Then we gained our right to the Plast oath. After all, before that you need to pass a system of tests, to prove that you are worthy of this oath.”

Currently, the number of participants in the London branch is 120 people. In 2020, the 15th anniversary of the Plast revival was celebrated here. The pandemic added new challenges: the usual activities had to be transferred online and new strategies for organising events had to be developed. However, during this period, the number of new Plast members only increased and none of the children left Plast.

Olha says that the most important thing in the organisation is team spirit. And personally, she enjoys working with children the most, when there is an opportunity to teach and at the same time develop with them.

“The main tool we have to give children is self-identity, cultural armament. We give it to them in different ways, mostly through the game. This is what I love most about my part of the job.”

In addition, the value of Plast lies in the opportunity to tell the world about themselves, present the country to foreigners, overcome stereotypes, and promote awareness of others. Olha claims that in recent years, British awareness of Ukraine has increased. In part, this is due to cultural events and news because modern politics, in her opinion, is based on culture.

“At least now there is no confusion of Ukrainian and Russian languages. Many people are well aware that we are not a part of Russia that has somehow broken away, but that we are a separate state that has always been that way. Sometimes, when we hold public events in our uniforms, people ask: ‘Who are they? What are these unusual scouts?’ The answer: ‘These are Ukrainian scouts!’. So we try to reach new awareness levels with our events. I think the events help a lot.”

Olha believes that Plast is culturally very important for the Ukrainian community in the diaspora because families are often nationally heterogeneous and family members identify themselves differently. When children are born, there is a need to create a friendly Ukrainian-speaking environment for children and Plast becomes just such a place.

“It is important to establish this aspect of identity. When a child living in the diaspora in the fifth or sixth generation clearly says: ‘I am Ukrainian.’ You might ask: ‘what’s so useful about that?’. In fact, your personal happiness depends on how well you know yourself, how honest you are with yourself, and how well you can determine what this life gives to you and what you give to life.”

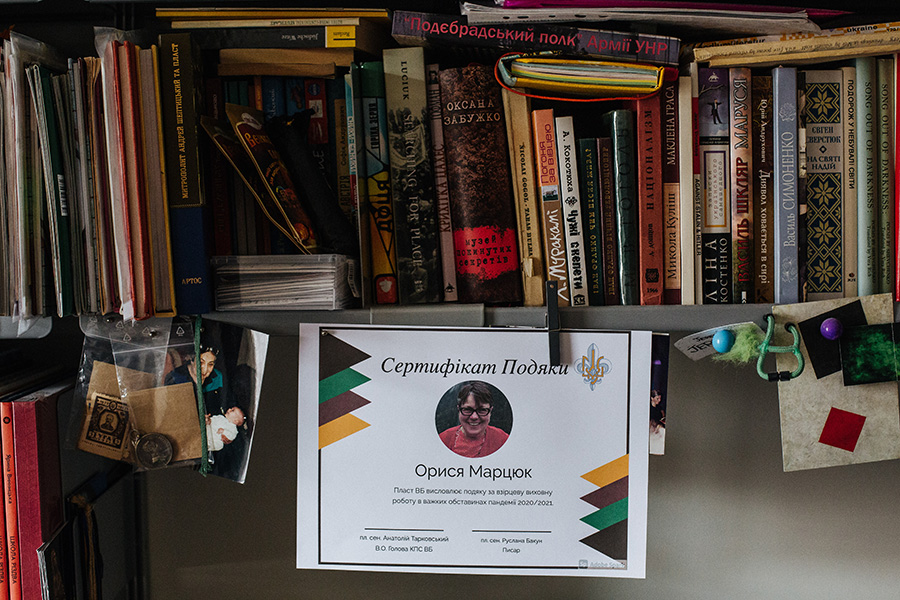

Values of Ukrainian scouts. Orysia Martsiuk

The thesis about the importance of Plast in the establishment and preservation of national consciousness is confirmed by Orysia Martsiuk, a liaison officer of the London branch.

Here: zviazkova

(Ukr. ‘liaison officer’) A member of the senior Plast who takes care of the administration of the branch and reports to the regional leadership, as well establishes contacts with the Scout Organization of Great Britain.“It was clear to me that without Plast it would not be possible to keep the language. I was so lucky that (in 2005 — ed.) there were three families of 2-3 children — enough to start Plast. We started meeting once a month, and that was very important.”

Orysia herself was born in emigration but has always associated herself with Ukraine. Her parents came from Ukraine but stayed in Germany after World War II. During the war, the Gestapo arrested her mother for her ties to the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN). She was sent to the Ravensbrück concentration camp. Her father held the position of financial assistant in the OUN and was acquainted with the leading figures of the organisation. Upon returning to Ukraine, both would obviously be repressed, so the family settled in Germany.

They lived in various cities, including Munich and Berlin. After graduating from school, Orysia began studying in Hamburg. Later in Berlin, she met her future husband and later moved to his homeland, the United Kingdom. Now she claims that the preservation of her identity was influenced by three factors: the Ukrainian church, Plast, and the birth of a son who had to be raised in a bilingual family:

“As soon as Yarema was born to us, I talked to my husband about which language to choose (for communication with our child — ed.): German or Ukrainian? Ukrainian was convenient for me because I didn’t know German or any other lullabies. When my mother-in-law, an Englishwoman, arrived, she was uncomfortable that I spoke only Ukrainian to my child. I had to explain it to her.”

The move to the UK in the 1990s marked many new challenges during the adaptation process. At that time, CYM, an Association of Ukrainian Women in Great Britain, and several other institutions already existed. Orysia visited a Ukrainian Catholic parish and sent her son to a Ukrainian kindergarten. Even though today the number of national organisations has grown, the woman still lacks a club where it would be possible to communicate in Ukrainian on some everyday topics, such as music or cinema. Orysia and her husband first visited Ukraine in August 1991.

“It was a time of great upheaval. We got in the car and drove off. The first time we spent the night in Mukachevo and had to book a room. My knees were shaking. I didn’t know, maybe my language was fiction and nobody would understand me. I had to try it out and it worked.”

With the revival of the London Plast, the woman became actively involved in its activities. She already had the necessary experience to do this because as a child living in Germany, she was also a Plast member. Among the materials of the family archive, Orysia keeps many pictures from that time, in particular from her first camp. Today, in the London organisation, she is not only a liaison between Plast and the British Scout Organisation but also a mentor and scribe of the branch. Even so, her activities are not limited to this: a wide range of activities in the branch allows everyone to be involved in various initiatives.

“Our projects are quite different. We started inviting young mentors and children (from Ukraine — ed.) to camps more than 10 years ago so that these young people could see how we organize Plast. Last year, our children raised a significant amount of money and sent it to the development of Plast in eastern Ukraine.”

The woman emphasises the deep values of Plast and their importance for every single Plast member: friendship, responsibility, trust, and willingness to help each other. Personally, it helps her keeping in touch with Ukraine and drawing inspiration from working together in the community.

“I am Ukrainian, although different, because I have never lived in Ukraine. All I know about Ukraine is second-hand experience. However, my emotional roots are definitely in Ukrainian culture. Ukraine for me is the chernozem (‘black soil’) from which I grow. It is in my soul.”

supported by

The project “Anthropological and ethnographic expedition by Ukraїner: Ukrainians in Great Britain” is realized within the program “Culture for change” with the support of the Ukrainian Cultural Fund (Ukraine) and the British Council (Great Britain). Ukraїner is responsible for the content of this multimedia story, which might not represent the official position of the Ukrainian Cultural Fund and the British Council.