This publication opens a series of articles that explain the Holodomor topic. First of all, we’ll try to find out what the Holodomor was, and what had preceded this genocide of Ukrainians and one of the biggest crimes against humanity in world history. We’ll also explain why the vital information on the Holodomor tragedy is still concealed and in whose best interest it is to keep it secret.

In 1921 the American Relief Administration (ARA) was negotiating with the Soviet Union the terms for their future operations in the Soviet state. Maksym Lytvynov, a Soviet diplomat at that time and later the People’s Commissar of the Foreign Affairs, in his response to an American representative said, “Food is a weapon.” And in 1932–1933 on the territory of modern Ukraine, the Soviet regime demonstrated what a devastating weapon it could become if possessed by totalitarian dictatorship. This was when millions of people died as a result of the deliberate Soviet policy. The Holodomor was recognised as a genocide by 17 countries. Today it is considered one of the biggest crimes against humanity.

Voronkiv of Boryspil district in Kyiv region — a village since the olden days, and a settlement in the times of the Cossack Hetmanate. A young bride in her national wedding dress, surrounded by her bridesmaids and friends, circa 1920s. The photo provided by the National Centre of Folk Culture “Ivan Honchar Museum”.

– … Perhaps the classic example of Soviet genocide, its longest and broadest experiment in Russification – the destruction of the Ukrainian nation.

This was the description of the Holodomor given in his article by Raphael Lemkin, a Polish lawyer of Jewish descent, who was the first to put the term “genocide” into the global context. The Holodomor is a proper name of the genocide of Ukrainians. This was a form of deliberate mass killings of Ukrainians during 1932–1933. It became possible by setting the unrealistically high quotas for the state grain procurement plan and through coercive expropriation of people’s land, property, and food — the measures that killed millions of Ukrainians. In this way Stalin was trying to suppress the Ukrainians who opposed collectivisation (a policy adopted by the Soviet government to transform traditional agriculture from private property to collective state-controlled ownership — ed.) en masse and who rose against the Soviet rule.

Raphael Lemkin

The author of the term “genocide” who also helped to create the legislative framework for recognising a crime as genocide. Its main element is the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. It was adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations on 9 December 1948. For the first time in the world history, this document defined genocide as any of the acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such.Over the long period of time this Soviet crime of destroying millions of people and their national and collective consciousness remained little known even in those places, where the events occurred. Total censorship, official statistics falsification, intimidation by the officials, and fear of retaliation had shushed the ringing voices of eyewitnesses and made them speechless. When faced with the choice — to be killed and to endanger their families or to remain silent — most of the eyewitnesses chose silence. Not a single document could prove their survival, which teetered on their physical and emotional edge, or the efforts they had to make to give birth to new generations. The memories of the people became the “archives”.

Today, after almost a century since the Holodomor, all these voices can be heard again. And the new generations can find out the truth and learn the lessons that cost lives of millions.

Before the Holodomor

In 1918 World War I was over. The national liberation attempts of Ukrainians resulted in the Bolsheviks’ occupation of Ukraine. On 30 December 1922 a new state arose that united hundreds of nations and cultures by means of military interventions and revolution — the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

— The mass murder of peoples and of nations that has characterised the advance of the Soviet Union into Europe is not a new feature of their policy of expansionism, it is not an innovation devised simply to bring uniformity out of the diversity of Poles, Hungarians, Balts, Romanians — presently disappearing into the fringes of their empire. Instead, it has been a long-term characteristic even of the internal policy of the Kremlin — one which the present masters had ample precedent for in the operations of Tsarist Russia. It is indeed an indispensable step in the process of “union” that the Soviet leaders fondly hope will produce the “Soviet Man”, the “Soviet Nation”, and to achieve that goal, that unified nation, the leaders of the Kremlin will gladly destroy the nations and the cultures that have long inhabited Eastern Europe. — Raphael Lemkin.

Volodymyr Lenin, the leader of the newly formed Soviet state, while waving banners and promoting the power of ideas, knew very well that in the post-war devastation the army needed to be fed. In Lenin’s view, Ukraine with all its fertile lands and well-developed farming was destined to become the source of food for his empire. That’s why in the 1920s, along with the miracles of illusory communism, the country witnessed shortages of food and provisions. While the rest of the world was renovating their cities, destroyed in the war, the Ukrainian SSR turned into a victim of a plan to build a global empire, — a plan which was destined to fail.

In 1921–1923 the post-war devastation, lack of working population, and a drought, accompanied by inadequate Soviet policy of grain procurement, resulted in the famine on the territory of Ukraine. Tons of grain were taken from the South of Ukraine, the region that had suffered from the drought the most, to become sold or to be sent to the Volga region in Russia, which also suffered from the famine. The Ukrainian SSR, which was de-facto an imperial colony, received no money or provisions in return.

Several millions of the dead from the famine of 1921–1923 could not deter the Soviets from their economic experiments on their way to the great communism. But even perversive ambitions of the communist leaders could not break the rules of life: the population needed food, and the state required an army and the management system. That’s why in 1921 a new economic policy (NEP) was introduced. NEP replaced “prodrazvyorstka” (a policy and campaign of confiscation of grain and other agricultural products from villagers — ed.) of the war communism era with the food tax. While prodrazvyorstka assumed confiscation of grain in the quantities set by the state and at fixed prices, the food tax required handing over 20% of the farm produce to the state. In the future, this rate was supposed to be lowered to 10% and should be allowed to be paid in monies.

This move by the Soviet government turned out to be a success: the situation in the country after World War I stabilised. Impoverished population, which was living in endless queues, lack of quality food and products, were nevertheless helping to support the system. But levels of dissatisfaction closely followed the growing rates of impoverishment in the newly formed empire.

slideshow

The Holodomor

Since 1929 the forced collectivisation started. In April 1930 a new law on grain procurement was passed, which required giving away to the state from ¼ to ⅓ of all harvested grain. This was the time when the grain prices on the global market went down because of the Great Depression. To keep the money flowing into its budget, the USSR had to significantly increase its volume of global sales. At the same time, it needed to keep up appearances pretending to be a successful and determined new state that was indulgently looking at a decaying capitalistic world on the eve of global revolution. To maintain its image, the USSR required money, and to make money they needed to increase volumes of grain procurement. They kept collecting the increasing volumes of grain from the population, providing nothing in return. So, by the early 1930s, there were over four thousand protests of farmers against this initiative of the state. The average farmers understood well: if they were capable of feeding their families with their hard work while the state was incapable to do so, the farmers did not want such a state. In farmers’ view, to give away their property and the results of their work to the state collective farms (“kolhosps”) for nothing would just be insane.

Most of Ukrainians were living in villages. In reality, the direction of grain procurement in the Ukrainian SSR and Kuban (the Russian region where Ukrainians were approximately half of the population — ed.) from purely economic changed to a national one. It then became a matter of eliminating the private ownership mindset of not just any farmer, but of Ukrainian farmers specifically, of destroying all of their national identity. That’s why from the very beginning the measures, taken by the Soviet regime, were very different for the Ukrainian SSR and the rest of the USSR.

After the first waves of coercive collectivisation, the farmers began to leave kolhosps en masse: they were taking back their inventory, cattle, and grain. Local protests and the acts of sabotage were spreading across the territory of Ukraine.

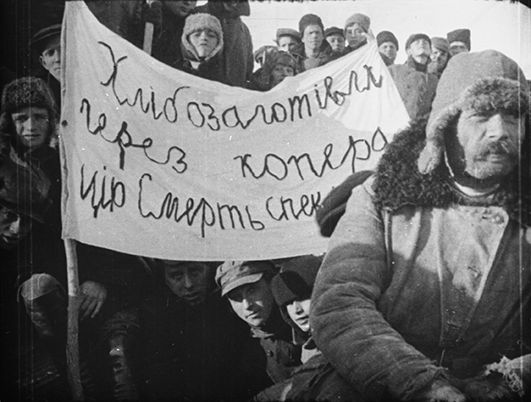

We can learn about the scale of those protests from various special reports of the State Political Directorate. The reports mentioned over 67 districts where the population was opposing the collectivisation policy.

According to one of such reports to Stalin on 28 December 1932, the regime arrested 12,178 people in the first 20 days of December. All of them were officially (and falsely) accused of sabotaging the grain procurement activities. In reality, this was a way to suppress any protests or opposition from the ordinary people.

In the era of limited communications and the only source of information being state press and radio, the “trick” worked just well.

A rally at the bulk point after giving away the grain. The Uli village of Kharkiv region 1932. Photo provided by the Pshenychnyi Central State Film, Photo and Sound Archive of Ukraine

On 7 August 1932 the resolution “On Safekeeping the Property of State Enterprises, Collective Farms and Cooperatives, and Strengthening Public (Socialist) Property” was enacted. This document was better known as “the Law of Five Ears of Grain”. For the theft of any collective farm property, the offenders could be executed by shooting; should they have any “extenuating circumstances”, they could “get away” with imprisonment for at least 10 years. According to “the Law of Five Ears of Grain”, people were not allowed to collect even crop residues. During that time special patrol brigades went from house to house in a village to confiscate all grain people had.

By 1932 an unrealistic grain procurement plan was set for Ukraine, imposing a quota of 356 million poods of grain. To officially approve this plan, Stalin’s closest associates — Kaganovich and Molotov — arrived in Kharkiv. Unlike most of their fellow party members, those two were clearly aware of Stalin’s intention to destroy any existing opposition at all costs, especially in Ukraine. At the conference on 6 July 1932 Kaganovich and Molotov accused the leaders of the Communist Party of Ukraine of failing the collectivisation and objected to the proposal of the Ukrainian communists to reduce the grain procurement quotas for Ukraine. Such a statement failed all attempts of the heads of kolhosps and local councils to emphasise that it was simply unrealistic to implement the plan. Kaganovich’s response meant no compromise and was very clear: the system would not come to a halt. The system intended to take it all.

Pood

One pood is roughly 16.38 kilogramsFollowing the initiative from Stalin, on 22 October 1932 the government accepted the resolution to create the Extraordinary Commissions in Ukraine and the North Caucasus, tasked with increasing the grain procurement rates. This resolution outlined the principles of formation and coordination for those very patrol brigades, which would later go from house to house, confiscating not only all the grain, but any other food people had. Molotov became the head of this Commission in Ukraine. Kaganovich took care of the North Caucasus. At that time he was the head of the Department of Agriculture and he was fully responsible for the agricultural policy of the Soviet Union. He was one of those who led millions of people to their death.

Nearly everyday the new documents and resolutions were issued by the Soviet regime; step by step they were taking away anything the villages had. Each new signature of an official would take away some more from once rich and confident proprietors. Every new letter in a resolution would push them closer to becoming speechless slaves of the system.

The state resolution “On Measures to Intensify Grain Procurement” from 18 November 1932 demanded the entire procurement plan to be accomplished by 1 January 1933. The document abolished all in-kind advance payments in collective farms and required to give back any grain which had been provided to collective farms for their catering needs. Those farms which did not meet the procurement plans, would be levied with in-kind penalties as punishment. The resolution introduced in-kind penalties in a form of additional provision of potato and meat, in the quantities equal to their procurement plans over one and a half years. It was allowed to apply those penalties multiple times. In reality, patrol brigades were confiscating anything edible they could find. At the same time, special units were implementing a “witch hunt” policy and consistently destroying any sources of unrest and disagreement, even if they were just potential. This was done through arrests and sending into exile to the remote regions of the USSR. In this way the punitive authorities were confiscating all provisions from all over Ukraine.

On 1 December 1932 the Soviet authorities banned trading in potatoes in those regions that could not fulfill their obligations of contracting and validation of the available potato deposits in collective farms. This banned list included 12 districts of Chernihiv region, 4 districts of Kyiv region and 4 districts of Kharkiv region. From December some of the other districts were banned from trading in meat and cattle. From 6 December those districts and certain villages were put on “black boards”, or “boards of infamy”. Any villages put on those “boards” were in fact sentenced to death. Supplying any provisions to such villages was banned, and people were not allowed to leave either. The villages would be surrounded by the army units to prevent any escape. The army would lock people inside their houses and then would watch the entire families dying.

Photo by Oleh Pereverzev

— The Holodomor was civilizational annihilation of Ukrainians. Joseph Stalin aimed to destroy such a civilizational phenomenon as Ukrainians, and to prevent the Ukrainian people from playing their independent role in history ever again. — Vitalii Portnikov.

On 16 January 1933 the Communist Party approved the final grain procurement plan for Ukraine with the quota of 260 million poods (4.2 million metrical tonnes). It was demanded for this plan to be “performed fully and unquestionably, at all costs”. In fact, the Soviet leaders confirmed: they were ready to watch the slow and painful death and moral decay of millions of people for the sake of “bright future of communism” for nameless masses.

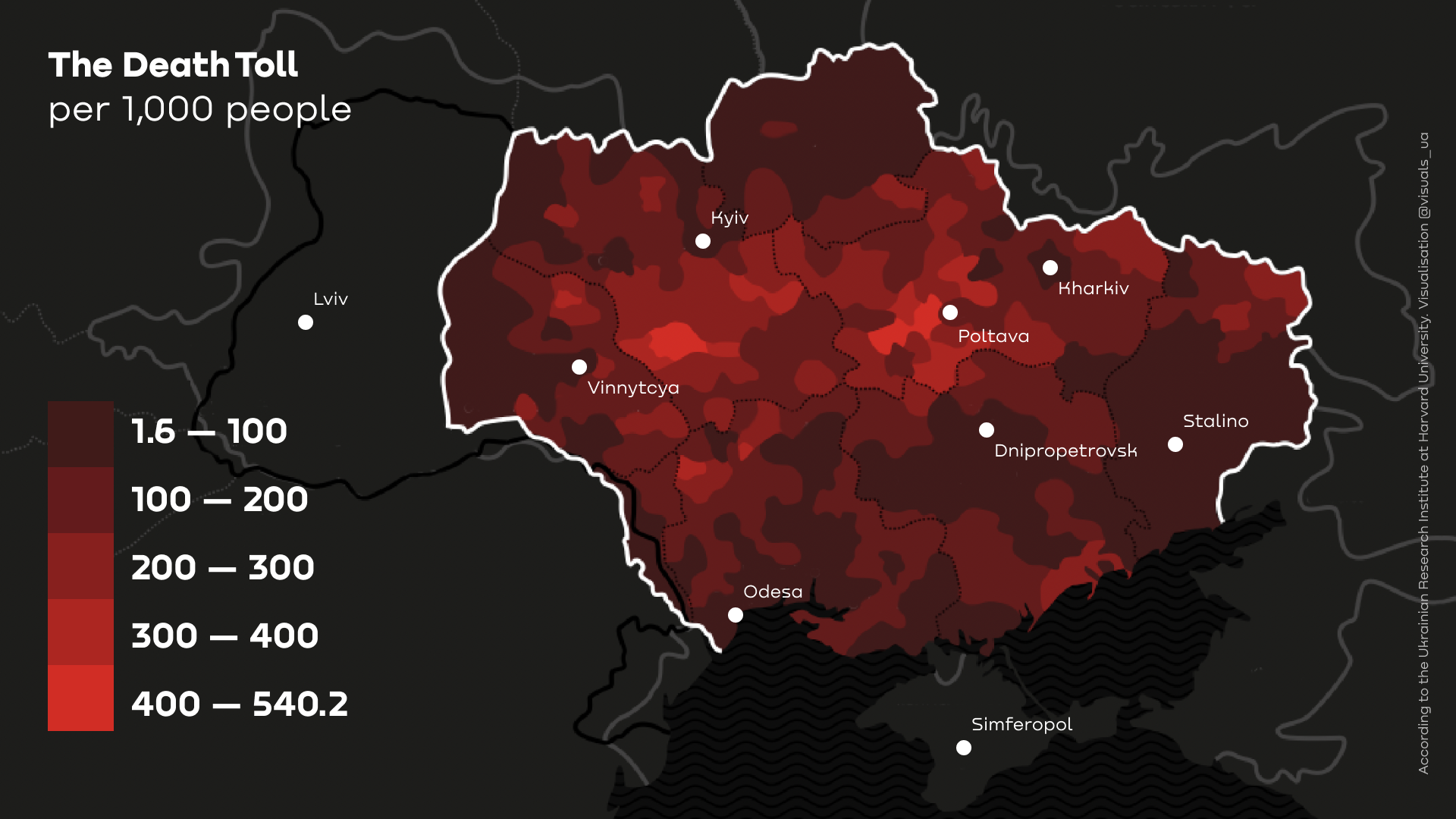

On 22 January 1933 another state resolution forbade leaving the Ukrainian SSR and Kuban territories. The period between January and July 1933 became the most severe in terms of the death toll, reaching its peak in deaths by June 1933. The Ukrainians who died during the Holodomor totalled in millions.

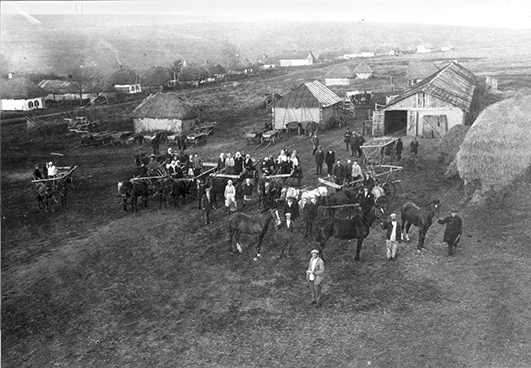

The farmers of the Illintsi village in Vinnytsia area at the bulk point during giving away grain to the state, 1929. Photo provided by the Pshenychnyi Central State Film, Photo and Sound Archive of Ukraine

Statistics Games

“Life has become better, life has become merrier,” — comrade Stalin proclaimed in December 1935. Life became “merrier” indeed. In 1934 People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs (or shortly “NKVD”) took control over Registry Office departments. Soon the fake justification of why too many people were dying, too little were born, and why the Soviet regime was not the one to blame or to protest against, was devised and presented in one of the state resolutions:

“The registration offices were often used by the class enemies who infiltrated these organisations to perform their counter-revolutionary and sabotaging activities, such as: registering one death several times, not taking records of newborns, and so on.”

Class enemies

Class enemies of the USSR (also called “anti-Soviet elements”) were intelligentsia, priests, workers, and well-off farmers, who were falsely accused of counter-revolutionary (anti-state) activities and sentenced to exile to labour camps or to death.This was a typical example of manipulating the facts and distorting the information in order to cover the state’s own inefficiency and systematic policy failures with false accusations of the innocent people.

There was another reason for such a decision. Back in 1934 Stalin emphasised: the population in the USSR was continuously growing. The new statistics was supposed to beat the data from the last census of 1926 and aimed to present a great view: the growing of the empire and the welfare of its population, eager to give birth to new baby comrades. The real data revealed million losses in 1932–1933 instead.

Preparations to the new census of 1937 were very ceremonial. Comrade Stalin himself edited the questionnaire and removed from it any questions about place of birth and relocations. On 1 January 1937 the Soviet government addressed people with the request to take the census very seriously because “through the numbers it had to testify the victory of socialism”. Since the mission was not an easy one — to “find” almost ten million people that had died in the genocide and not to embarass comrade Stalin — the authorities first went on their rounds to talk to the population in person.

But “somehow” the great plan has failed. On 6 January 1937 the census was finished within a day — much sooner than it was expected. On 10 January one of the census managers received a memorandum: “Looking at the provisional figures, the census results in the Ukrainian SSR make all this information classified.” And indeed: comrade Stalin could not accept the failed celebration of the Soviet state’s blooming era or the lack of several million people. But if there was no celebration, someone had to be made responsible for that. And so it was: the main “killjoys” at the Stalin’s party became the organisers of the census — they were immediately repressed. For 1939 the new census was planned which became a real hoax to hide the truth.

The fact that mortality rates were deliberately falsified by the Soviet regime is barely shocking. The system that made millions of people silent could not allow the world one day to find out all the bones underlying the ways of proletarian revolution.

It is because of that “playing with statistics” various scientists and research centres of the Holodomor provide their own figures of the death toll, discovered by learning from many different sources and archive documents. What’s worse: the absence or inability to find the official calculations open the way for manipulations. For some historians, this creates an excuse for not recognising the fact of the Holodomor as genocide. And Russia, for example, as a “successor of the Soviet Union”, directs its efforts on pulling in the reduced numbers of the victims and even questions the fact that the Holodomor was the Soviet regime’s deliberate policy.

Statistics always has its pros and cons. On the one hand, it turns a personal tragedy into a measurement error on paper. On the other hand, it provides an opportunity to follow the trends and to get a deeper understanding of the events, to “zoom out” and observe the complete picture. It also helps to avoid political manipulations and conjecture in the absence of direct evidence. The stories of the eyewitnesses combined with the archive documents, which weren’t destroyed, formed the evidence base that helped to recognise the Holodomor as genocide. This evidence has also been supported by declassified archives of the Security Service of Ukraine which are now publicly available. They helped to prove that the Soviet regime was deliberately destroying the Ukrainian nation. Each testimony is a real survival drama of individuals and entire villages, of the revival and continuation of their life, with new generations and endeavors.

But the history of the genocide in Ukraine still has many gaps. It is not enough just to be able to learn about the crimes of the Soviet regime — it is important to be able to mark the scale of those crimes clearly, based on the statistics data. This could be done, in particular, with the help of all those documents that have been taken out from Ukraine and are now stored in the Kremlin archives. The true and accurate number of the dead would become a sober fact which is required for holistic understanding and articulation of the historic trauma of this magnitude.

supported by

The material was published in cooperation with the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide with the support of the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation.