The term “repatriation” is heard more and more as discussions around returning Ukraine’s cultural heritage gather steam. Some are looking to other nations’ colonial and postwar pasts as a guide for how these return processes might unfold.

This material seeks answers to the question of how Ukraine should return its looted cultural property. Is it possible to hold Russia accountable for cultural crimes? What can be learned from the experiences of other countries that sought to return stolen cultural heritage?

Repatriation — the return of stolen or illegally exported objects of cultural heritage — has a decisive role in restoring historical justice and national memory. If an object was damaged or lost due to hostilities, the aggressor state must transfer cultural property of comparable value to the affected country or pay compensation for the destruction. These obligations are regulated through the following international conventions:

– Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property (1970)

– Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (1972)

– UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects (1995)

Russia is currently blatantly ignoring these international principles and norms, but sooner or later it will be held accountable for its actions.

The repatriation experience after World War II

The return of cultural objects to their rightful countries after World War II is considered one of the most extensive exercises in cultural repatriation. Logically, the core repatriation processes should have taken place in the first decades after the war, but history took an unexpected turn. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, it was found that the Soviet Union had secretly kept thousands of European cultural objects that were thought lost during World War II. This sensation swept the world and triggered a new wave of searching for and returning lost artefacts. Restoring rightful ownership to cultural property has become an essential element of many states’ policies, as well as the subject of interstate negotiations.

Return of cultural property to Germany, Austria, and Hungary

Even though Germany and its former allies were the aggressors in World War II, a lot of their cultural objects were looted in 1944-45. For instance, Soviet soldiers would use railway carriages to bring stolen property to the Soviet Union in large quantities. Consequently, representatives of postwar Germany made many claims to Moscow because the territory of the then-Russian Soviet Republic was home to almost the majority of their looted items of historical, artistic, and archeological value. However, Moscow disregarded these claims as an attempt to undermine the results of World War II and allegedly found no reason to return cultural property to the parties that lost the war.

Dr. Karol Estreicher came to Kraków with works of art stolen by the Germans during World War II

In 1998, the Russian Federation adopted its law “On cultural values transferred to the Union of the SSR as a result of World War II and those located on the territory of the Russian Federation.” The law stated that the cultural property of Germany and its allies that had ended up on the territory of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR) would be deemed the property of the Russian Federation. It also demanded partial compensation for the damage that Germany and its allies had caused to Russian cultural property during the war. This law was, in fact, a legalised seizure of foreign cultural property.

Russia’s decision to consolidate its ownership of stolen cultural property more than fifty years after the end of World War II has come under fire. Germany and other countries have tried to resume the repatriation process for their cultural objects, with some success. Through bilateral agreements, Russia returned more than one hundred ancient stained-glass windows to the Marienkirche in Frankfurt (Oder). These windows had been appropriated by the Soviet authorities after the war and sent to the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. In addition, in 2006, the Russian Federation adopted a law on the return of the well-known library of the Sárospatak Theological Academy of the Reformed Church (one of the oldest educational institutions in Hungary). Austria also managed to repatriate a book collection that the Soviet military had smuggled to the USSR in 1945. In March 2013, the State Duma of the Russian Federation ratified an agreement to return this collection of almost a thousand unique editions, dating from the 15th to the 18th centuries, that used to be part of the former library of the Austro-Hungarian princes of Esterházy.

Stained-glass windows from the Marienkirche. Photo from open sources.

Restitution of private collections to Holocaust survivors

While repatriation takes place at the government level and refers to returning cultural objects to a state, restitution is the process of returning cultural objects to an individual or community. After World War II, the international policy regarding the restitution of private cultural objects to Holocaust survivors proved to be successful.

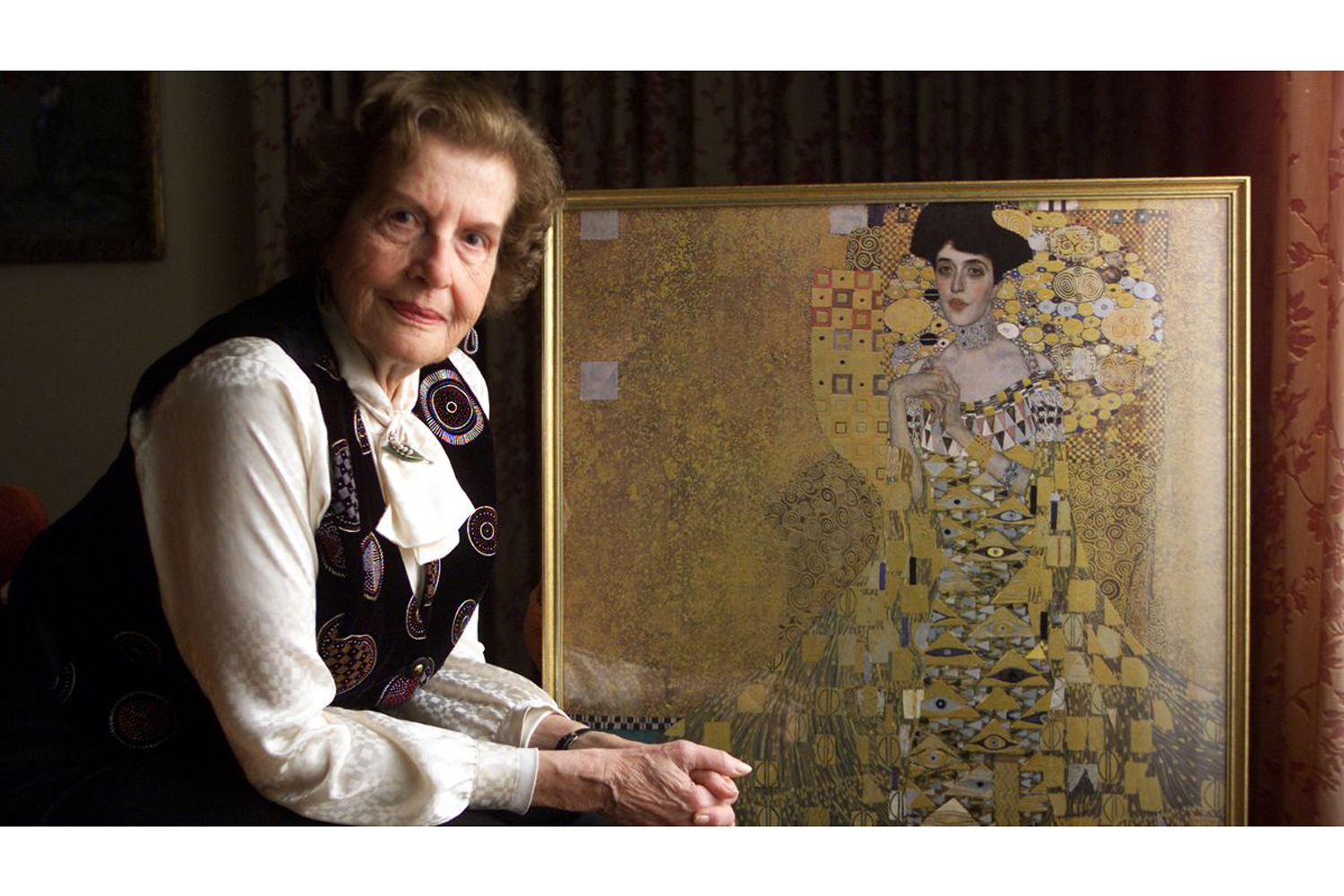

For instance, the 2004 ruling of the Supreme Court of the United States in the Republic of Austria v. Altmann case is considered a prime example of the process of restitution. Maria Altmann, an American of Austrian origin, demanded the return of five paintings by famous Austrian artist Gustav Klimt that the Nazis had confiscated from her family during World War II. Since their confiscation, the paintings had been housed in the Galerie Belvedere in Vienna. In 2000, Altmann went to federal court in Los Angeles and filed a lawsuit against Austria. The case reached the Supreme Court of the United States. Eventually, the parties brought the arbitration process to Austria, where, in 2006, the gallery was compelled to return the paintings to Altmann. Numerous similar cases took place after World War II and, in addition to returning stolen items to Holocaust survivors, these restitution processes sparked important changes at the international level. In December 1998, the Washington Conference developed the Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art. Although not binding, these principles were a crucial step in driving international cooperation in the search for cultural property lost during World War II and its repatriation or restitution.

Maria Altmann with a painting by Gustav Klimt. Photo: Lawrence K. Ho/Los Angeles Times, Getty Images.

The return of Polish cultural heritage

There are also successful examples of post-war repatriation of cultural property to Poland. During World War II, Poland was almost completely looted, with more than 500,000 Polish works of art, constituting approximately 70% of its cultural heritage, ending up in museums around the world. During the first post-war years, Poland managed to return a small amount of cultural property that had been taken abroad. However, in 1965, Polish communist authorities stopped this process. Repatriation could only resume after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Consequently, over the past 30 years, Poland has regained dozens of historical and artistic objects that were stolen by the occupying forces in World War II.

One of the most resonant cases of Polish repatriation centres around The Lady with an Ermine, a work painted by Leonardo da Vinci around 1489-1490 in Milan. At the beginning of the 19th century, likely during a trip to Italy, Polish prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski purchased it for his mother, Izabela Czartoryska, who was an art connoisseur. Initially, the painting was stored in the first museum in Poland, the Gothic House in Puławy. After the November Uprising (1830-31), Czartoryski moved it to Paris. Later, The Lady with an Ermine returned to Poland, but during World War I, it was transferred to the Old Masters Picture Gallery in Dresden for safe-keeping. In 1939, in anticipation of the German occupation of Poland, it was moved again, this time to the Polish town of Sieniawa. However, the Nazis found it and transferred it to the Kaiser Friedrich Museum in Berlin (now the Bode-Museum). In May 1945, a Polish-American commission discovered Lady with an Ermine among the possessions of Nazi leader Hans Frank when he was trying to flee to Germany. At the Nuremberg trials, Frank was sentenced to death, and the painting was handed back to Poland. Now it is on display again in the Czartoryski Princes’ Museum in Kraków.

“Lady with an Ermine” by Leonardo da Vinci. Photo: Stanisław Rozpędzik/PAP.

Another successful case of returning looted cultural property to Poland is that of Aleksander Gierymski’s painting titled Jewish Woman with Oranges (1880-1881), sometimes called Orange Vendor. Two years before the end of World War II, the painting disappeared from the National Museum in Warsaw. It was considered lost for decades. However, in the mid-2000s, it was unexpectedly discovered at an auction house near Hamburg. Returning Jewish Woman with Oranges became a challenging task for lawyers because German law stipulates that after 30 years of continuous possession of an illegally exported work of art, the previous rightful owner cannot legally take the work back. So, the owner of the auction house in northern Germany demanded monetary compensation for transferring the painting. The Polish party and the auction house reached a legal and monetary agreement and Jewish Woman with Oranges was transferred to the National Museum in Wrocław in 2011.

“Jewish Woman with Oranges” by Aleksander Gierymski. Image source: Wikipedia.

After the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Poland intensified its battle to return its cultural property that is still in the territory of the aggressor country. In September 2022, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Poland sent Russia a note demanding the return of seven works of art looted by the Soviet army during World War II. As of the end of September 2022, Russia had still not considered any of Poland’s 20 requests to return the works.

Since Poland lost most of its movable objects of material cultural heritage during World War II, it has ensured that its cultural policy prioritises the return of these treasures. Since 1992, Poland’s Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, supported by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Poland, has kept a nationwide electronic register of movable objects of cultural heritage that disappeared during World War II. Data from this register is published on a special website. Then, all the collected information is sent to international offices, foreign museums, and institutions holding auctions. Wide media coverage has helped locate most of Poland’s previously lost cultural objects and start the repatriation process.

Poland is also making significant efforts to raise public awareness about its national cultural heritage, especially concerning stolen objects. For example, in 2013, the Polish government launched an online exhibition called “The Lost Museum.” It displays stolen and repatriated works and has prompted public discussions about the importance of culture in nation-building and preserving a people’s identity.

Poland’s emphasis on cultural diplomacy has also seen success with Japan. The Madonna and Child painting by Italian artist Alessandro Turchi, stolen by the Nazis from a private Polish collection during the occupation, was identified in January 2022 at an auction in Tokyo. This painting dates from the late 16th or early 17th century. Just like Lady with an Ermine, it was included in the catalog of the most important works of art that were illegally exported from Poland during World War II. As a Nazi ally, Japan was one of the aggressor states in this war. It rightly recognised the Polish origin of the painting and voluntarily returned it to Warsaw.

A painting stolen by the Nazis was returned to Poland. Photo: ポーランド広報文化センター Instytut Polski w Tokio.

Also in 2022, the Ministry of Culture of Poland launched a large-scale promotional campaign in which Polish celebrities starred in 50 short films about stolen works of art. With the celebrities’ support, the Ministry of Culture sought to communicate the extent of Poland’s loss of cultural heritage during World War II. Ministry representatives; leading art critics; directors of the largest museums in Poland; famous actors, athletes, musicians, and journalists; and other public figures took part in the campaign. For instance, Olympic fencing silver medalist Radosław Zawrotniak, journalist Igor Janke, and satirist Krzysztof Skiba all participated.

For International Museum Day on May 18, 2024, Poland is organizing multimedia exhibitions of lost artworks. Poland’s Ministry of Culture claims that sharing images of stolen cultural objects is the first step towards returning them home. This is something that Ukraine could also do as a first step towards repatriating its cultural property stolen by Russia. The growth in interest in Ukrainian products, both in Ukraine and abroad, would make such an initiative even more relevant.

Restitution of Ukrainian cultural valuables

In World War II, Ukraine was the arena for some of the bloodiest battles between enemy armies. After Germany announced its offensive, the Soviet Union issued a decree on June 27, 1941, titled “On the procedure for the evacuation and replacement of personnel and valuable property.” It allowed the evacuation of museum artefacts deep into the USSR, i.e., into the then-rear Russian Soviet Republic. Due to the Nazis’ sudden and rapid advance through Ukraine, it was impossible to evacuate cultural property from nine of Ukraine’s oblasts — and the German army stole these exhibits. One of the main goals that encouraged the Nazis to commit “cultural” looting was Hitler’s desire to establish a museum in his hometown of Linz, Austria. It was supposed to be the largest in the world, where the most outstanding works of art from around the globe would be stored. In addition, according to the Germans’ plans, this looting would finally prevent Ukrainians from being able to study their past, which would allegedly speed up recognition of the supremacy of the Aryan race. According to Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg, destroying national cultural property was enough to eradicate a nation in as little as one generation.

The Soviet army’s attitude towards works of art was no less destructive and arbitrary. Some valuable objects were used as firing points or strongholds on the battlefield; others were simply looted. The Soviet army also used a scorched-earth policy, destroying everything that could not be evacuated so that the enemy army could not take advantage of it. As a result, Ukraine was left without thousands of valuable items of cultural heritage.

After World War II, almost all the cultural objects that the Nazis had stolen from the USSR were transferred to Moscow as compensation. No objects were ever returned to Ukraine. Russia appropriated all the repatriated property, allegedly according to a 1998 law, even though this law provides for the return of stolen cultural property to all the countries that were formerly part of the USSR. Serhiy Kot, a senior researcher at the Institute of History of Ukraine of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, noted that if you count the number of objects returned to the Soviet Union, approximately 74% of the most culturally important artefacts were Ukrainian.

To this day, there are no unified statistics on the number of items stolen from Ukraine between 1941-1945. According to data published by the Ministry of Culture of Ukraine in 1987, Ukraine lost approximately 130,000 art objects during World War II. However, this figure is an estimate — it may be much higher because the full extent of the damage that Ukrainian cultural heritage has suffered is unknown.

Evacuation of cultural valuables in the USSR. Photo from open sources.

After regaining independence, Ukraine was denied participation in repatriation processes for a long time. Negotiations regarding the return of the lost heritage did not involve Ukraine: they only addressed the Russian Federation. This situation began to change when Ukraine took initiative and voluntarily gave over 30 items attributed to the famous German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe to Germany. German-Ukrainian cooperation was gradually improving. However, most of the returns of Ukrainian cultural property from Germany were initiated by private owners. Official repatriation appeared to be more complicated. Despite occasional returns of Ukrainian cultural heritage, Germany believes that “after World War II, Germany returned Ukrainian cultural property to the former USSR and thereby fulfilled its international legal obligations.”

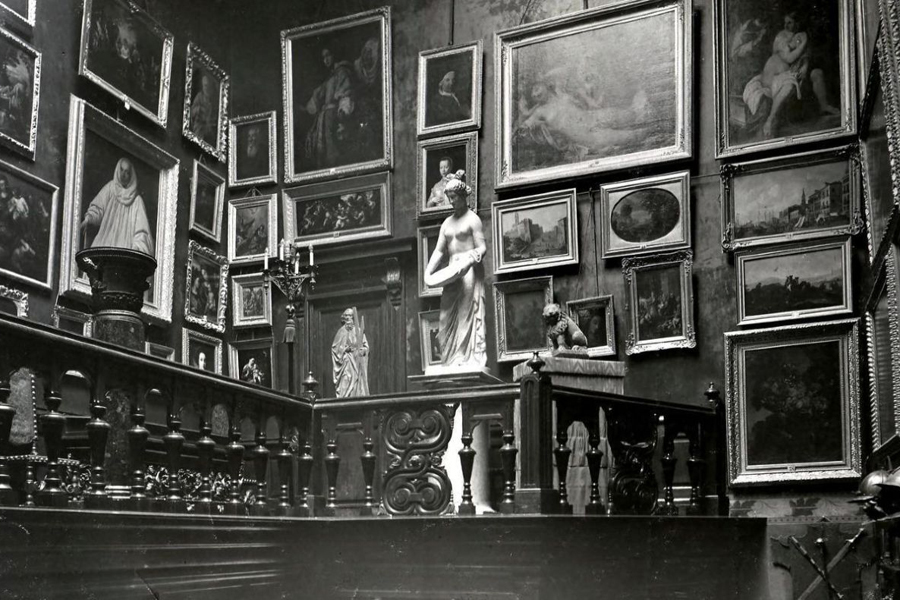

Olena Zhyvkova, Deputy Director General of Research at the Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko National Museum of Arts, points out that Ukraine has lost more artefacts than any other European country. As a result of World War II, the Khanenko Museum lost about 27,000 items. In its framework of cultural cooperation, between 1955 and 2004, the museum returned 89,601 works of art to European Union countries through processes of repatriation. And it was Germany that received, by far, the most — 89,459 objects. How many items did this Ukrainian museum receive from Germany and EU countries in return? None. Olena Zhyvkova adds:

“In 1998, researchers at the Khanenko Museum published an English-language catalogue of paintings lost as a result of World War II, and later put it on the German Lost Art Foundation website. We are still updating this e-catalogue, finding new information about lost items. Each of the 474 paintings mentioned in it is a repatriation object and, therefore, subject to the rule that the aggressor state must transfer cultural property of comparable value to the affected country. I consider the legal regulation on paying compensation inappropriate for movable objects of cultural heritage. Not because the artefacts are priceless, but because money cannot help restore them. Only other cultural objects can partially compensate for the cultural trauma, which will cover the black holes left on the walls of our museums or in our minds.”

The interior of the Khanenko Museum at the beginning of the 20th century. Photo from the Museum archive.

The theft of Ukrainian cultural property is still taking place today as Russia continues its war against Ukraine. History suggests that Russia will not freely return what it has stolen: this can only be resolved through an agreement on Ukrainian terms after Ukraine’s victory, or through international trials. However, there are some known cases when, after it restored its independence, Ukraine did manage to return stolen objects of material cultural heritage from Russia and other countries.

2010

One of the few cases in which Russia did decide to return looted objects to Ukraine was the transfer of two early Christian tombstones from the 5th-6th centuries to the Tauric Chersonese National Reserve in Sevastopol. In 1964, under Soviet rule, they were taken to modern St. Petersburg for temporary preservation. The tombstones were the last of 12 exhibits on display at the Leningrad Museum of the History of Religion and Atheism.

Sevastopol, the ruins of Chersonese. Photo: Real Crimea.

2011

The day before Easter, Germany returned a unique collection of historic pysanky (Ukrainian for painted Easter eggs — tr.) that the Nazis had stolen from Ukraine during World War II. The then-German ambassador to Ukraine, Hans-Jürgen Heimsoeth, personally handed over the pysanky, which had been stored in the Höchstadt regional museum. The return of these pysanky was a continuation of the German-Ukrainian repatriation process, which had started back in 1993. Throughout the whole process, Ukraine regained several hundred cultural objects.

A collection of historic “pysanky”. Photo: Radio Svoboda.

2015

Arcadian Landscape, a painting by Dutch artist Cornelis van Poelenburgh, was returned to the Khanenko Museum. This cultural object belonged to the collection of Ukrainian patrons of the arts Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko. It had been looted from Kyiv during the German occupation. In 2011, a European auction house included it in a canvas sale announcement on its website, and the painting’s origin was confirmed within a year. The Khanenko Museum enlisted benefactor Oleksandr Feldman to help with the case, and he soon bought the canvas and solemnly handed it over to the museum.

“Arcadian Landscape” by Cornelis van Poelenburgh. Photo: Khanenko Museum.

2016

Estonia returned an illegally exported medieval Viking sword to Ukraine. The sword was confiscated from a citizen of Belarus at the Luhamaa checkpoint on the Estonian–Russian border in the winter of 2016. Upon examination, it turned out that the artefact is about a thousand years old. At first, Estonia was going to transfer the cultural object to Russia, but it later confirmed the sword’s Ukrainian origin.

Viking sword. Photo from open sources.

2018

The return of Sketch with a House by Kharkiv artist and celebrated landscape painter Serhii Vasylkivskyi remains mysterious. Like many other paintings, this cultural object was stolen by the Nazis during World War II. For more than 75 years, the canvas was considered lost forever. However, in late 2016, the Kharkiv Art Museum received a letter from the commissioner of the Criminal Police of Berlin, who informed them that an anonymous bidder had discovered a painting similar to Sketch with a House at a German auction. A German-Ukrainian commission worked for a year and a half to prove it belonged to Ukraine. In the end, no legal grounds were found to return the painting, but an anonymous man bought it and delivered it to Kharkiv. The bidder did not disclose his identity: he only said he was interested in Vasylkivskyi’s work of art and promised to visit the museum.

The “Sketch with a House” painting by Serhii Vasylkivskyi.

2020

In January 2020, Ukraine succeeded in returning Mykhailo Panin’s painting titled Secret Departure of Ivan the Terrible Before the Oprichnina, which was illegally exported during the German occupation. This cultural object was in the possession of a former Swiss soldier who immigrated to the USA in 1946. In 1986, the man died, and his private house in the city of Ridgefield, Connecticut, where the painting was stored, was purchased by an American couple. In 2017, the couple put the Ukrainian canvas up for auction. The Dnipro Art Museum immediately responded with a demand to return the stolen cultural object. The United States confiscated the painting and later handed it over to Ukraine.

Another successful case was the return of An Amorous Couple (The Lovers or The Prodigal Son with the Prostitute), a painting by Pierre Louis Goudreaux, to the Khanenko Museum. It had belonged to the collection of Ukrainian art critic and collector Vasyl Shchavynskyi. In 2020, seven years after the museum team managed to stop New York-based Doyle Auctions from selling the painting, the United States returned the artwork for free through a court decision.

“The Lovers” by Pierre Louis Goudreaux. Photo: Khanenko Museum

2022

In September, U.S. Customs and Border Protection confiscated valuable objects that Russians tried to take to the United States. Among them were Scythian Akinakes swords from the 6th–5th centuries BC, a polished flint axe from the 3rd millennium BC, Cuman tribe sabres from the time of Kyivan Rus’, and many other valuable Ukrainian cultural items. They were returned to Ukraine in March 2023.

Scythian Akinakes sword. Photo from open sources.

2023

Before Russia’s occupation of the Crimean Peninsula, the Kyiv Museum of Historical Treasures and four Crimean museums organised an exhibition titled Crimea: Gold and Mysteries of the Black Sea, later popularly referred to as Scythian Gold. This exhibition brought together more than 600 artistic valuables and antiquities from the eras of the Sarmatians, Huns, ancient Greeks, and Goths. It was held in the German city of Bonn from July 2013 to January 2014 before making its way to the Allard Pierson Archaeological Museum in Amsterdam, where it was supposed to stay only until the end of May 2014. However, the Russian invasion fundamentally changed the intended course of events: these Crimean valuables have not returned to Ukraine. In 2021, the Amsterdam Court of Appeal ordered the transfer of the artefacts to Kyiv. Russia responded by filing a complaint on behalf of museums in occupied Crimea the day before launching its full-scale invasion. However, Russia has not found any support in the Dutch court process.

After almost nine years of litigation, on June 9, 2023, the Supreme Court of the Netherlands recognised Scythian Gold as Ukrainian cultural heritage. Therefore, it will be returned to Ukraine.

Scythian gold helmet from the 4th century BC, one of the exhibits at the “Scythian Gold” exhibition in Amsterdam. Returned to Ukraine. Photo: Treasury of the National History Museum of Ukraine.

Ukraine still has a long way to go to restore justice. Nevertheless, with the help of international repatriation experiences and the support of partner countries, the legal return of its cultural heritage is possible.