This material is an attempt to tell what has happened to the Ukrainian language since the beginning of its existence and how it has formed into what Ukrainians use now. Ukraïner will try to explain how, despite all the prohibitions, the Ukrainian language has not only survived, but it has also spread far beyond the borders of Europe, with the numbers of people in Ukraine who use Ukrainian steadily growing as well.

What was there before the Ukrainian language?

Each modern language, Ukrainian included, began to develop a very, very long ago, at a time for which there is no definite data. In a world where there were no means of instant communication, and the fastest means of transportation was horseback riding, people had far fewer opportunities to communicate with anyone other than their nearest neighbours. At times there were foreign merchants or conquerors, or, on the other hand, the peoples’ own trading activities and conquests that helped to expand contacts. There were no grammar or textbooks for learning the language, so our ancestors knew it only as it was spoken in their hometown or village.

Today, it is known that the Ukrainian language does not exist by itself. It is related to many other languages, which are called Slavic. The similarities between the different Slavic languages are not accidental. They create a complex system of correspondences. For example, one can notice dissimilarities in the roots and suffixes of the same words. The Ukrainian -ів corresponds to the Russian -ов and the Polish -ów (pronounced /uf/), such as in Lviv, but Lvov and Lwów; Krakiv, but Krakov and Kraków. Such dissimilarities between different languages mean that they had been developing according to different laws. And if philologists understand these laws, they will not only be able to predict what Ukrainian roots will look like in related languages (though not always), but they will also be able to assume what those elements looked like before these laws came into force and before these dissimilarities formed different languages.

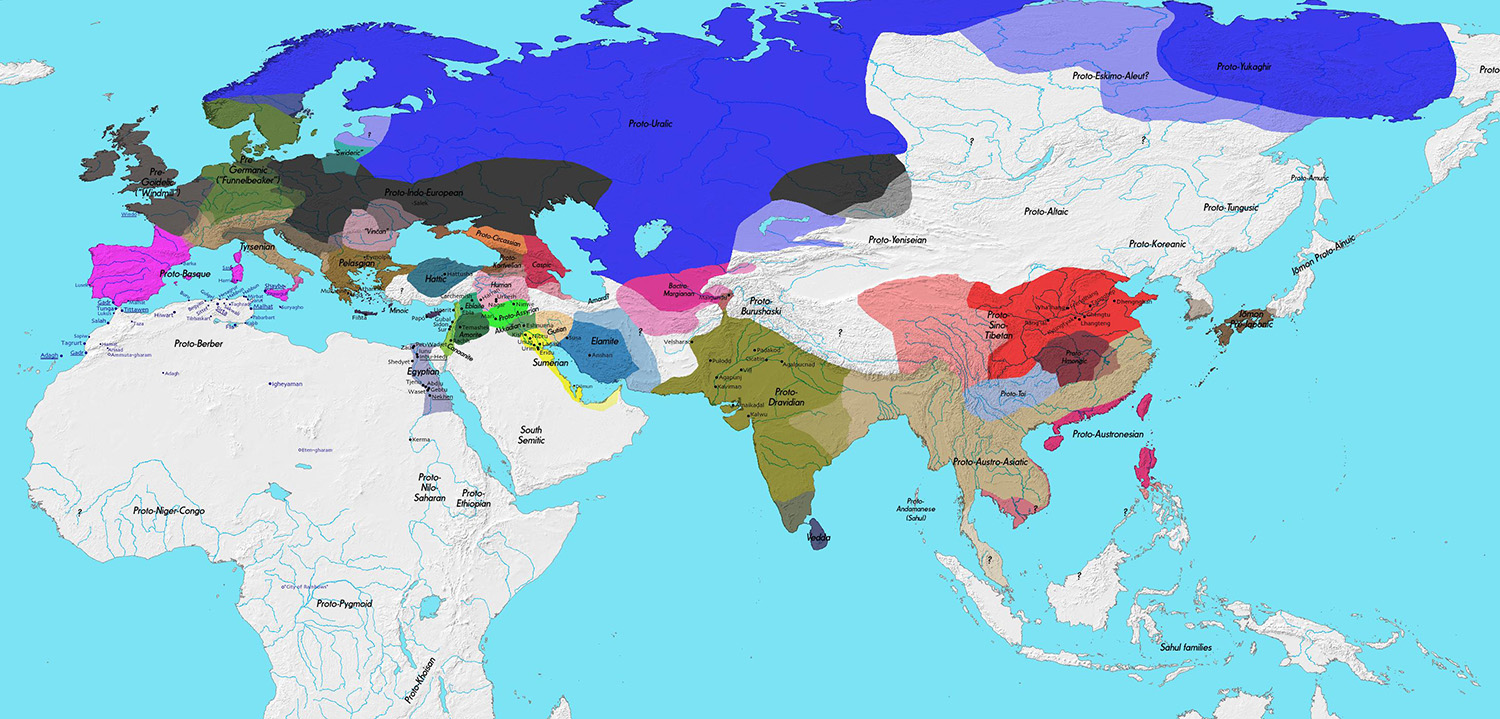

The hypothetical, reconstructed language spoken by the Slavs long before they even took the name “Slavs”, is called by philologists Proto-Slavic. However, it did not appear by itself but separated from the Proto-Indo-European language like Proto-Germanic, Proto-Baltic, and other ancestors of dozens of modern languages. But, of course, this is just a theory. Scientists do not know whether these languages really existed. Most likely, there was a massive amount of subdialects that were once mutually understandable but have significantly changed over time.

Ancestors of modern languages..

How did Ukrainian form from the hypothetical Proto-Slavic language?

Philologists cannot say much about the development of the Slavic languages prior to more or less final settlement of the Slavs on these territories. From the disintegration of the Proto-Slavic linguistic unity, i.e., somewhere from the 6th century, the Proto-Ukrainian period begins, which lasts approximately until the 11th century. The major features of the Ukrainian language as a system appeared at the end of the 11th through the mid-12th century. At that time, the formation of the language was taking place in two main areas — Polissia and Podillia. Linguist Yurii Sheveliov calls these territories “the subdialect regions”, emphasising that it is inappropriate to refer to these initial dialect forms as languages.

Young George Yurii Shevelov (1934—1936, Kharkiv). Image from Dmytro Antonovych Museum-Archives in UVAN, New York, USA.

What did these two regions do to the language? Across the territories where the Russian and Belarusian languages will later emerge, all consonants before the front vowels (e, i, ĕ) are palatalised. Therefore, the Russian words хлеб (bread) or дерево (tree) are pronounced /xlɛb/ and /dɛrɛvo/, while in the Ukrainian language, consonants before e remain non-palatalised: дерево /derevo/, небо /nebo/. In the word хліб (bread), the vowel, which originated from the Proto-Slavic ĕ (it was later denoted by the letter ѣ (“yat”), turned into i, which makes the previous consonant palatalised.

Also, the combinations of sounds цв- and кв- in words цвісти and квітнути (to blossom) have been preserved until now in the Ukrainian language, while there is only цвести in the Russian literary language (some forms with кв- are present in dialects), and kwiatnąć in Polish. The Proto-Slavic sound combination кв- did not change in Polissia, but transformed into цв- in Podillia. And here, you can see another dissimilarity. The Proto-Slavic sound ĕ (represented by the letter ѣ (yat) in ancient Ukrainian written records), turned into і in the Ukrainian language (represented by letters i and и), but into е in Russian (denoted by the letter e), and into e or a in Polish (ia in writing, as the previous consonant is palatalised). Compare how the word “white” sounds in these three languages: Ukrainian білий /bilyʲ/, Russian белый /bɛlyʲ/, and Polish biały /bjauy/.

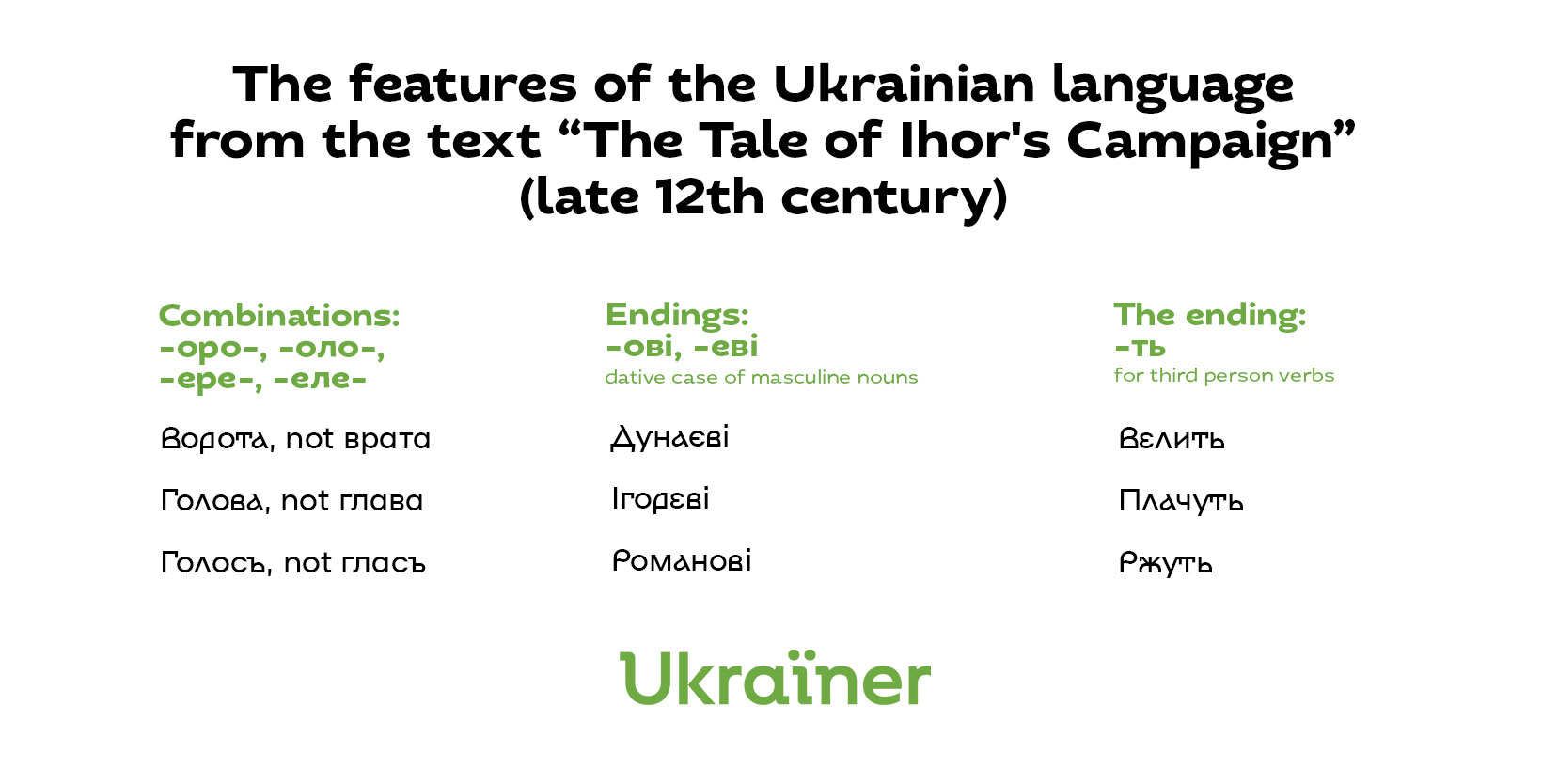

Today, scientists know that certain features of the Ukrainian language have been directly inherited from Proto-Slavic, for example, the endings -ові, -еві in the dative case of the singular masculine nouns (such as домові, князеві), the vocative case (друже, княже, брате), the ending -мо in the first person plural of verbs in the present and future tenses (даємо, зробимо), and the alternation of consonants г, к, х with з, ц, с respectively in the dative and locative cases of singular nouns (слузѣ, на березѣ, в рѣцѣ), etc.

Instead, in certain phonetic features, the language in Ukraine deviated from Proto-Slavic. Already in the second half of the first millennium AD ґ /g/ was pronounced instead of г [ɦ]. Another example, е after ж, ч, ш, й before the following non-palatalised consonant changed into о: жена (wife) became жона; человѣк (man) — чоловік; єго (his) — його; пшено (millet) — пшоно.

With the appearance of the first written records, the period of language development referred to as Old Ukrainian begins.

At this stage, Ukrainian acquires most of the features by which it is recognised today. The most important and least apparent change for modern people was the reduction in the number of vowels and the increase in the number of consonants. Ukrainian used to have the nasal sounds ę and ą, that are preserved in the Polish language. Short vowels, represented by ь and ъ, have either become full vowels or disappeared. Of course, both Ukrainian and Belarusian still have the soft sign (ь), and Russian also has the hard sign (ъ). However, they have not represented independent vowels for a long time. Early Proto-Slavic language had 10 vowels, 10 diphthongs (i.e. combinations of two vowels), and only 15 consonants. In Old Ukrainian, according to some claims, only 9 vowels remained, but there were about 30 consonants.

Considering the number of changes that have taken place in Ukrainian phonetics, it is possible to roughly determine the degree of affinity across different Slavic languages. Yurii Sheveliov compares the modern Slavic languages based on phenomena remaining common to them after Proto-Slavic collapsed. The closest to Ukrainian is Belarusian, followed by Russian, Bulgarian, Polish, and Slovak. In terms of vocabulary, according to the linguist Konstiantyn Tyshchenko, the most relative to Ukrainian is again the Belarusian language (84% of vocabulary is related), followed by Polish (70%), Slovak (68%), and Russian (62%).

Is the Old Slavonic Language the same as Old Ukrainian?

No.

The thing is that the written language was brought to the Ukrainian and Belarusian lands along with Christianity. The book language was significantly different from the spoken one — in fact, these were different languages. Moreover, scholars claim that religious and secular written records (for example, laws, and decrees) were also written in different languages. There were two literary languages in the 11th century:

1. Old Slavonic, also referred to as Old Church Slavonic, was based on one of the dialects of the Old Bulgarian language and was specifically created to translate the Bible from Greek into a more comprehensible language for Slavs.

2. Old Kyiv language, also referred to as Old East Slavic or Old Ukrainian, was the language of the formal documents and other secular writings on the territory of Kyivan Rus.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to reproduce exactly what language people spoke at that time because there were no voice recorders or social networks. However certain features can be reconstructed because they penetrated the local written languages. For example, in Izbornik of Sviatoslav or Sviatoslav’s Collections of 1073 and 1076, there are features that are characteristic of the Ukrainian language today and that differentiate it from its neighbours. For instance, the ending -ть in the third person of verbs, confusing ѣ with и, which means that the sound denoted by the letter ѣ (yat) was pronounced like i.

Since the 12th century, it is more appropriate to speak not about Old Church Slavonic, but about the Kyiv Izvod of Old Church Slavonic. The Izvod was a version characterised by changes accumulated from the spoken language, which influenced the reading (the aforementioned misreading of the letter ѣ) or the spelling of words: къдє, сьдє in the Kyiv Izvod; къдѣ, сьдѣ in the Moscow Izvod. For example, the letter ѧ (small yus), which represented the nasal sound ę in Old Slavonic, was used in ancient Ukrainian records as an interchangeable letter with ıа. After all, the ancient spelling of yus gradually turned into the Ukrainian letter я.

However, it is difficult to differentiate which ancient records belong to ancient Ukrainian. Older manuscripts usually do not indicate the place or time of creation and when they do, they do not always tell the truth. At the same time, even a book created somewhere in Novgorod or Suzdal can belong to the written records of the ancient Ukrainian language, if its copyist came from Ukraine, and vice versa. Thus, Sheveliov notes that the inscription on the Cross of Euphrosyne of Polotsk enables classifying it as a monument of ancient Ukrainian literature. Meanwhile, part of the graffiti of St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv was obviously created by the Moscow Izvod speakers, meaning that it does not belong to the monuments of Ukrainian literature.

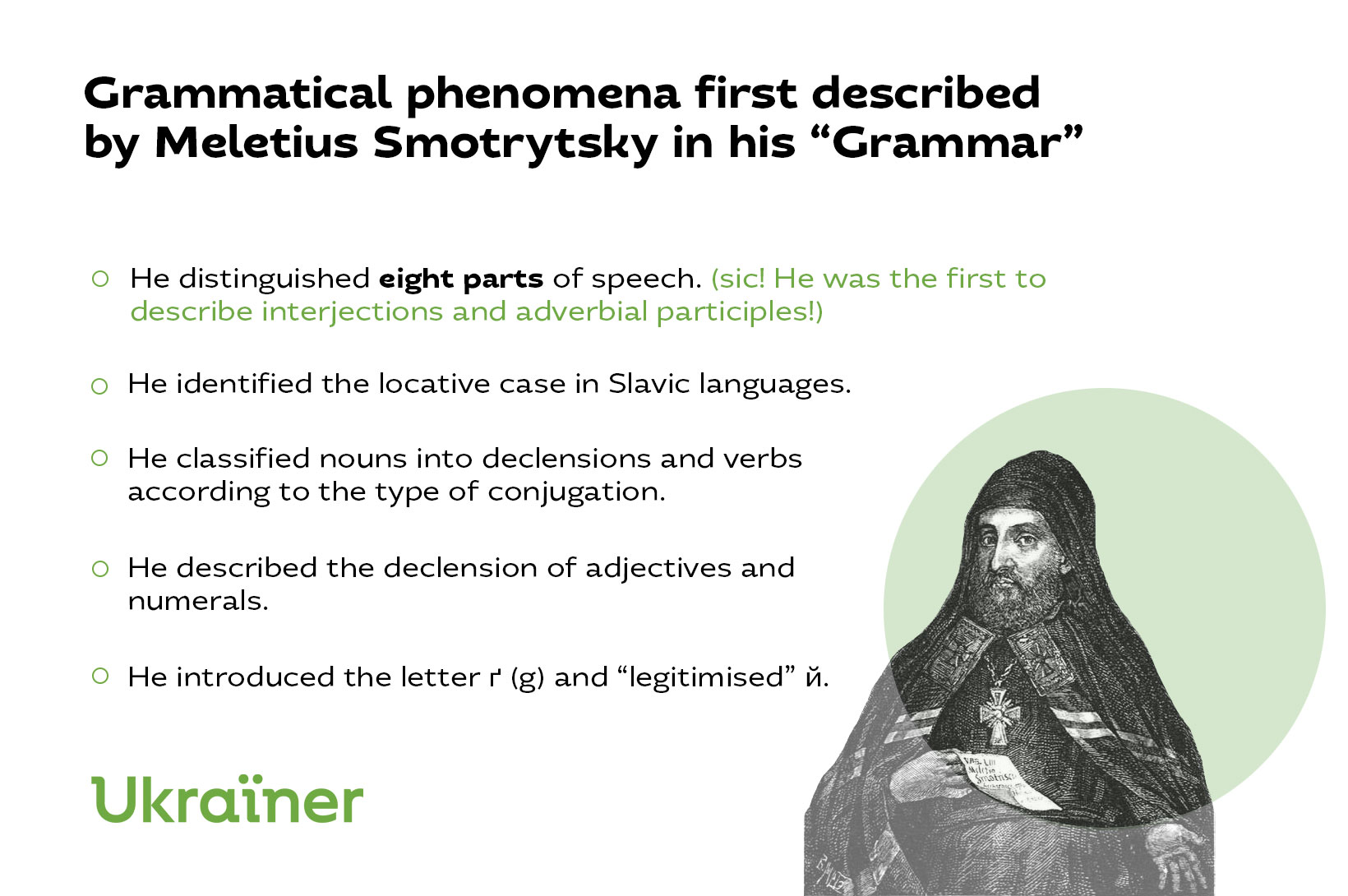

The Kyiv Izvod is the edition of the Old Church Slavonic language in Kyivan Rus. Linguists use the term Ukrainian edition of the Old Church Slavonic language to refer to the written language after the collapse of this state. There were other editions: Russian, Belarusian, Serbian, etc. The Ukrainian edition of the Old Church Slavonic language was described by Lavrentii Zyzanii in Grammar (1596) and codified by Meletius Smotrytsky in his own Grammar (1619).

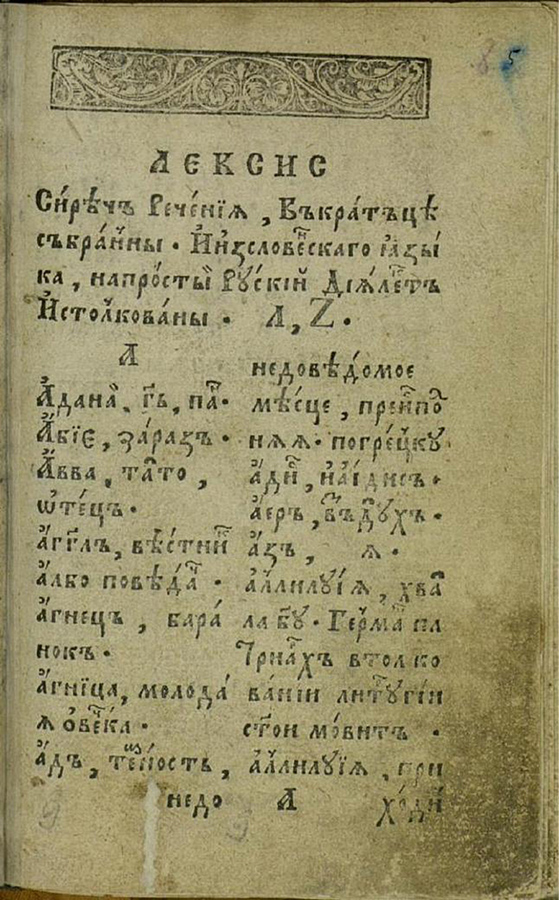

The Ukrainian edition of Church Slavonic was used in the services by the Church of the Kyiv Orthodox Metropolitanate and the Greek Catholic Church. Simultaneously with Lavrentii Zyzanii’s “Grammar”, the first Church Slavonic-Ukrainian dictionary was published. The Church Slavonic words in it were interpreted in a language that was derived from the Old Kyiv language, and was closer to the language people spoke.

Lavrentii Zyzanii, Lexis (1596). Source: Wikipedia.

A similar phenomenon — clear differentiation between written and spoken languages — is inherent in many cultures. For example, in Western Europe, Latin was the language of education, science, and religion for a long time, but people used different languages in their everyday life. At the beginning of the 14th century, Dante Alighieri wrote The Divine Comedy in the spoken language of the Tuscan region because he lived there. This dialect became the basis of literary Italian.

Or, for example, Ottoman Turkish was used as an administrative and literary language in the Ottoman Empire from the 13th to the first third of the 20th century. Still, most citizens used the so-called “vulgar Turkish” (kaba Türkçe), which formed the basis of the modern Turkish literary language.

Is it true that Ukrainian poet Ivan Kotliarevskyi wrote his famous Eneida poem to finally bridge the gap between the spoken language and various versions of the written one, as it is often taught at schools?

It is true that in the 18th through the 19th century a lively interest in peoples, their traditions and way of thinking grew throughout the whole of Europe. This triggered the formation of national liberation movements, which later led to the rise of many modern European states: Germany, Italy, Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, etc.

But Kotliarevsky had other reasons for writing in a living spoken language.

The fact is that with the rise of the Russian Empire, the Ukrainian version of the Church Slavonic language began to be replaced by Russian. From 1720, the decree of Peter the Great on the Left-bank Ukraine allowed the printing of books only in the Russian version. The decree of 1729 required the rewriting of all government decrees and orders from Ukrainian to Russian. From 1740 all the records of the Hetmanate were to be kept in Russian. In 1794, the Metropolitan of Kyiv Samuyil Myslavskyi issued a new decree that made the Russian version of Church Slavonic obligatory for the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. From Russia’s point of view, it was a movement towards the standardisation of language, but from the point of view of the Ukrainian academy, with its centuries-old book and literary traditions, these were repressions and prohibitions.

When all the literary languages that existed in the Ukrainian lands were banned, what was left for the intelligentsia to do except writing in Russian, a language that was not spoken there and whose tradition did not extend there except for several hundred years?

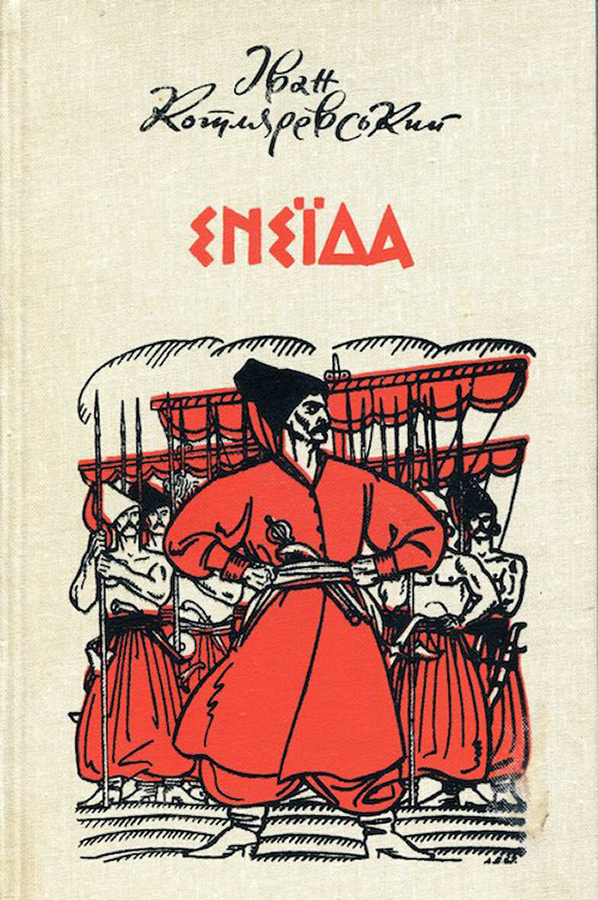

The Aeneid by Ivan Kotliarevskyi, edition of 1968, illustrated by Anatolii Bazylevych. Source: http://uartlib.org.

The intelligentsia found an alternative: they began to use the living spoken local language in writing because no one had banned it yet. In 1798, Ivan Kotliarevskyi’s Eneida was published in St. Petersburg as an attempt, a game, and a provocation.

Did Kotlyarevskyi’s Eneida immediately encourage others to start writing in the living Ukrainian language?

Eneida was indeed a popular work among the intellectuals of that time, but reading in the vernacular language was strange and unusual, so there arose a controversy over what the Ukrainian literary language should be, whether it could be used to write serious works, not only humorous ones.

In the 1830s, other works by Kotliarevskyi written in the vernacular were published in Kharkiv: the plays Natalka Poltavka and Moskal-Charivnyk (The Muscovite-Sorcerer), and Hryhorii Kvitka-Osnovianenko’s novels, among which were not at all humorous, but serious works, such as Marusia.

In 1840 Shevchenko’s Kobzar was published in St. Petersburg. Shevchenko’s uniqueness is that he, a native of Naddniprianshchyna, used his local dialect in his poems but selected the words that were clear to every Ukrainian, no matter where they came from, which gave Shevchenko’s poetry an all-Ukrainian character.

Taras Shevchenko. Illustrator: Oleksandr Grekhov.

In Naddniprianshchyna, translations of the iconic works of world literature — the Bible, works by Shakespeare, Goethe, Byron, Heine were published in the living Ukrainian language.

At the same time, in Halychyna, which was part of another empire, Austro-Hungarian, similar processes took place as in “Greater Ukraine”. In 1848, the first newspaper in the Ukrainian vernacular Zoria Halytska was published in Lviv. The 1830s and 1860s were the years of cultural revival in both central-eastern and western Ukrainian lands, when many ethnographic materials, Ukrainian-language sermons, and teaching materials on the Ukrainian language were published.

Therefore, the language based on the version spoken by people was increasingly used in writing. Attempts were even made to standardise it.

Is it true that the modern Ukrainian literary language is based on the Poltava-Kyiv dialect?

Yes, because the authors who were the first to write in the living Ukrainian language came from Poltavshchyna, Naddniprianshchyna and Slobozhanshchyna regions, but the modern Ukrainian literary language has also been significantly influenced by the Western Ukrainian dialects.

In the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries, about 470 censorship orders were issued in the Russian Empire, the most notable were the Valuev Circular of 1863 and the Ems Ukaz of 1876. These decrees prohibited the publication of books in Ukrainian (including those based on the vernacular language): first all except fiction, then all, including fiction and even musical notations. The Ems decree also prohibited the use of the Ukrainian language in schools, churches, journalism, newspapers, magazines, science, formal documents, translations, public speeches, theatre, etc.

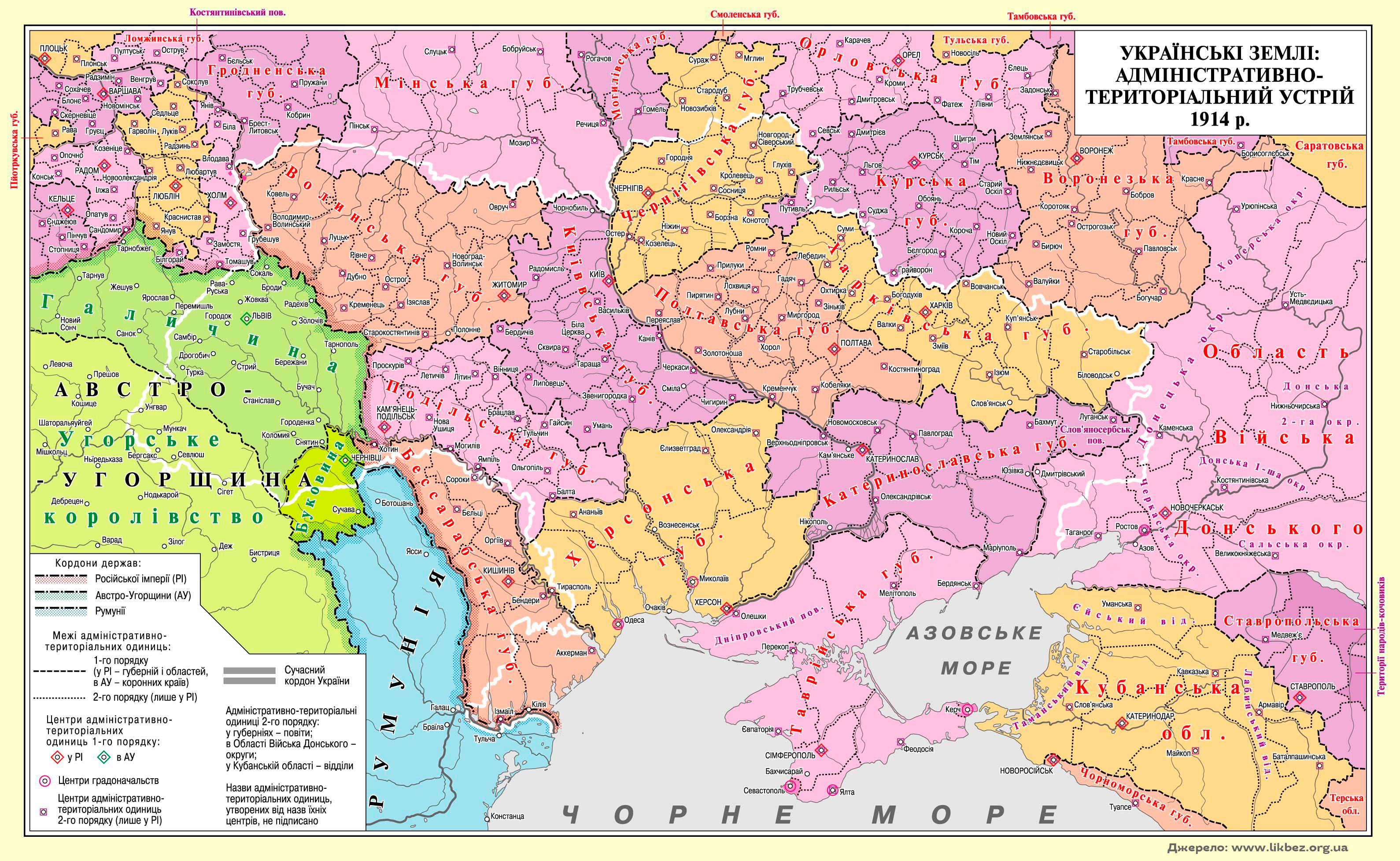

Banned across the Russian Empire by the Valuev Circular and the Ems Ukaz, book publishing in Ukrainian had to move to those Ukrainian lands that did not belong to the empire at that time: Halychyna and Bukovyna. Then, the local authors understood that one day Ukraine would become united, so they aspired to become part of “Greater Ukraine” and focused on their literary language.

Administrative division of Ukraine of 1914. Map created by Dmytro Vortman. Source: www.likbez.org.ua.

But when book publishing moved to Western Ukraine, i.e. in the late 19th — early 20th centuries, the language of artistic, journalistic, scientific publications that were published in Lviv and Chernivtsi became naturally saturated with words of the local dialects, as well as socio-political and scientific terms that were used in Halychyna and Bukovyna. There the terminology was more developed than in “Greater Ukraine”, because the Ukrainian-language press had been publishing for more than a decade.

Therefore, at the beginning of the 20th century, the Ukrainian literary language was significantly supplemented with words that originated from the Western part of the country.

How did the period of national liberation struggles of 1917-1921 affect the Ukrainian language?

It was during the time of the Central Rada that the term “Ukrainization” was first used. As Yurii Sheveliov writes, “after a break of almost two hundred years, the Ukrainian language becomes the official language for legislation, administration, army, and assemblies”. Ukrainian was introduced in schools. Ukrainian-language educational institutions were opened including the Ukrainian People’s University, the Scientific-Pedagogical Academy, and the Academy of Arts. Of course, there was a lack of textbooks, terminology, and specialists. So in the summer of 1917, there were about a hundred courses in Ukrainian studies for teachers, and a private “School Education Society” started publishing school textbooks. For educating adults, the “Prosvit” network was created, which had its own libraries, organised lectures, etc.

At that time, the standardisation of legal terminology began. Many specific legal terms, obviously taken from the times of the Kozaks, can be found in the texts of the Central Rada. Many legal terms were loanwords, the language of the West Ukrainian People’s Republic documents were very similar but contained more Latinisms.

During the Hetmanate, the government promoted the Ukrainization of primary schools. They opened new secondary and high schools with Ukrainian as the language of instruction while retaining the Russian ones that already existed. The latter would open departments of Ukrainian studies. Also, there were summer courses in Ukrainian studies. To increase the prestige of the Ukrainian language and culture, state institutions were established: the National Library, the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, where dialectological, orthographic, and terminological commissions functioned. “The most important rules of Ukrainian spelling” were approved.

Regarding the period of the Directorate, immediately after coming to power, on January 3, 1919, it issued a law “On the state language in the Ukrainian People’s Republic”, which required the use of Ukrainian in the army, navy, government, and other public institutions, citizens having the right to turn to state institutions in their native languages. Ukrainian was made a compulsory subject in higher education establishments.

At that time, the armies in the Ukrainian National Republic — UNR — and in Crimea, which was not part of the UNR, were Ukrainianized. Revolutionary events and the national liberation movement in mainland Ukraine affected the sailors of the Black Sea Fleet whose personnel were 70-80% Ukrainians at the time so greatly that they became the nucleus and main engine of the Ukrainian Sevastopol community. By the end of April 1917, Ukrainian soldiers formed a great number of Ukrainian clubs and councils in their land units and on ships. The Ukrainian publishing house Atos was founded in Simferopol.

Is it true that the Soviet government has always done nothing but ban the Ukrainian language?

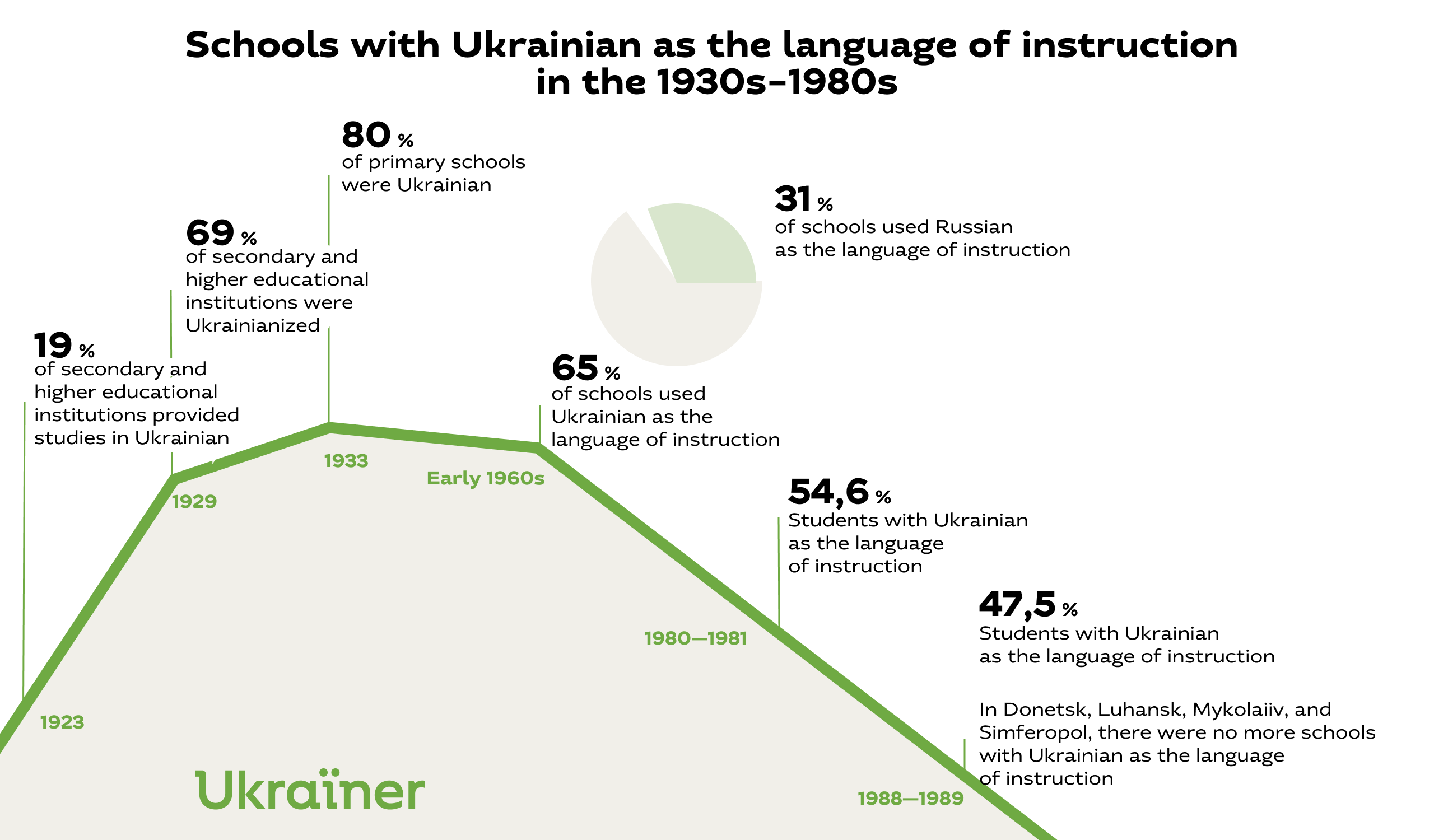

No, the Soviet period was not consistent in this respect. In 1923-1932, the period of Ukrainization lasted, when Ukrainian rapidly developed and spread.

Ukrainization was taking place within the policy of “korenizatsiya” (deepening roots), which proclaimed that the governments of the union republics, the working class, and the population of cities, in general, would be significantly replenished by their indigenous citizens (still mostly peasants): in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic — by Ukrainians, in Belarus — by Belarusians, in the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic — by Crimean Tatars, etc. Also, the national languages would be given official, or even dominant status.

In Ukraine, korenizatsiya policy became Ukrainization. In the novel The City (1928), Valerian Pidmohylnyi describes how the leading character, who came from a village to study in the city, started teaching the Ukrainian language to officials and made good money. So, now peasants could teach something to the townspeople, particularly authorities if they did not know Ukrainian. According to the slogan “uniting the city and the village”, the cities were rapidly filling with peasants, and thanks to this they were also Ukrainianized. The Ukrainian language was introduced in schools. By the way, Ukrainization also took place in those lands that were not formally part of the USSR but were ethnically Ukrainian: Kuban, Kursk, Voronezh, and the Far East (Zelenyi Klyn).

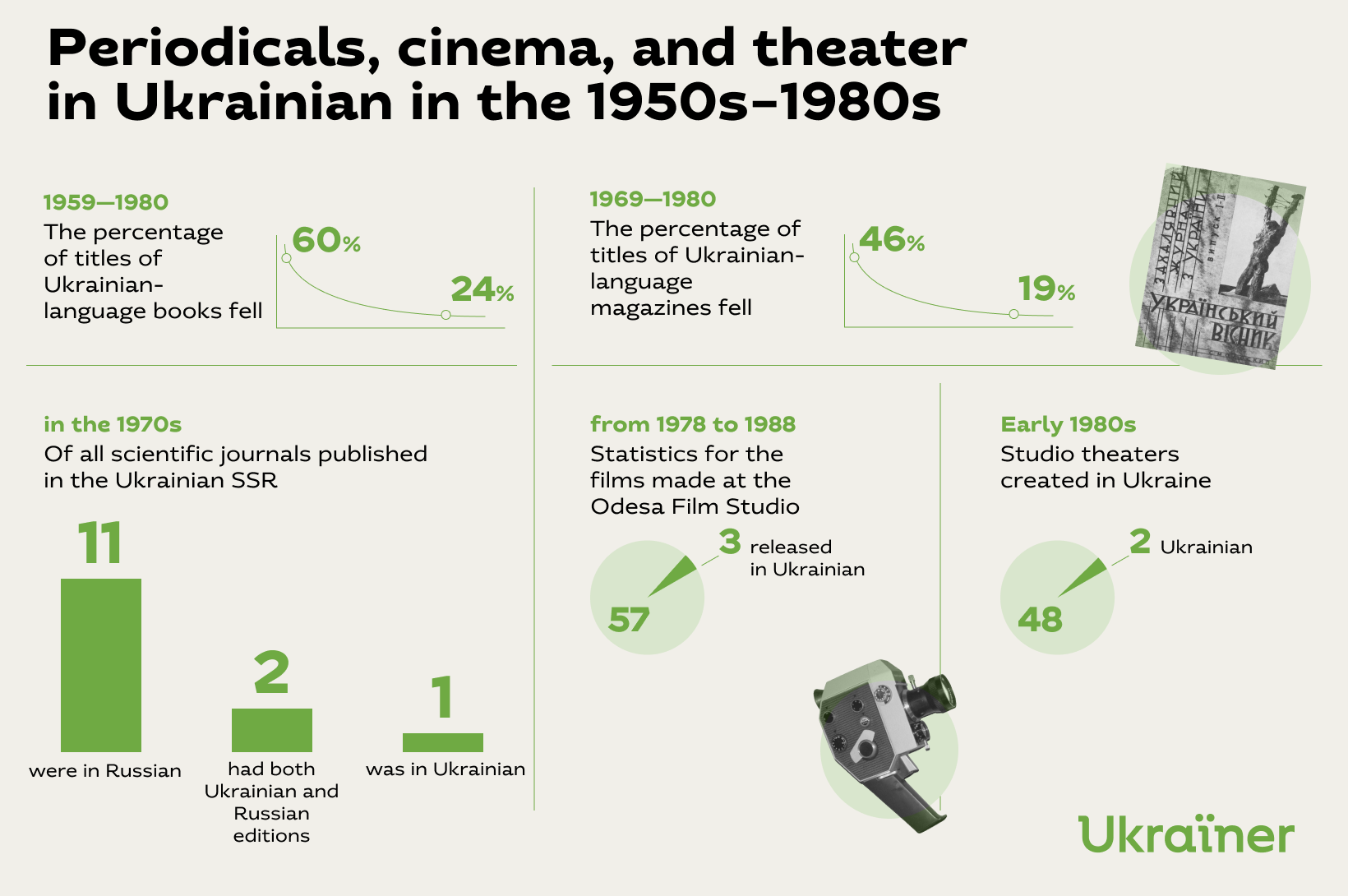

Ukrainian books were published, theatre and cinema were also Ukrainianized.

If in 1922 there were no Ukrainian-language newspapers, in 1933 there were 373 out of a total of 426 titles, and 89 magazines out of 118. It is recorded that in 1933, 83% of books in the USSR were published in Ukrainian. In 1931, 66 theatres out of 88 staged plays in Ukrainian.

Ukrainian school in Nova Sotnia settlement in Eastern Slobozhanshchyna, Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, 1933. Source: Wikimand.

At that time, the language not only spread — it was organised and developed. Much effort was focused on compiling dictionaries, in particular, in 1924-1933, three volumes of the unprecedented Russian-Ukrainian dictionary, edited by Ahatanhel Krymsky and Serhii Yefremov, were published. This dictionary provided rich material on specific Ukrainian vocabulary. The fourth volume was prepared, but not published because Stalin’s pogroms against the intelligentsia began. All scientists’ work was declared sabotaging by the authorities.

In 2016–2017, the Potebnia Institute of Linguistics and the Institute of the Ukrainian Language of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine reprinted three volumes of the Russian-Ukrainian Dictionary, edited by Ahatanhel Krymsky and Serhii Yefremov.

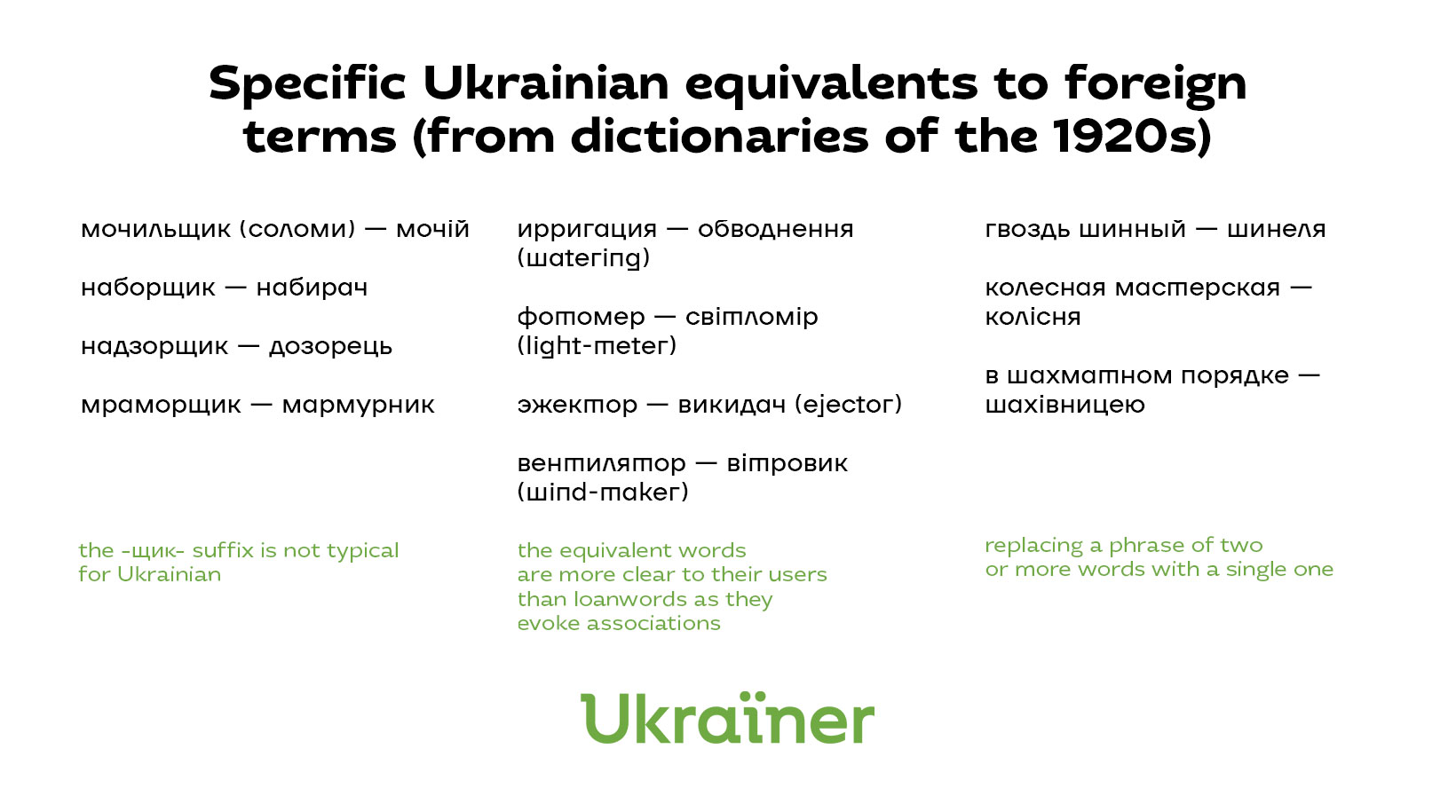

In the 1920s, massive work was being done in the field of terminology — a number of terminological dictionaries were published. This created the opportunity to use Ukrainian in various areas of both urban and rural life.

In 1918-1933, 83 terminological dictionaries were published, 30 of them by the Institute of the Ukrainian Scientific Language. Dictionaries were large and small (as appendices to textbooks, manuals, and magazines). They covered a variety of topics from “Dictionary of technical terms of sugar beet technology” to “Pure mathematics terminology”.

In the course of Ukrainization, the orthography was standardised. There were earlier attempts to do it (the so-called Kulishivka, Drahomanivka, and Zhelekhivka norms, compiled in the 19th century), but they did not take into account the peculiarities of different regions where the Ukrainian language was in use. In 1925, a commission of 20 scientists was appointed, including some representatives of Western Ukraine which did not belong to the USSR at the time. In 1928, the orthography was approved and given the status of mandatory. Today it is known as “Kharkiv orthography” or “Skrypnykivka” grammar (after Mykola Skrypnyk, who was the People’s Commissar of Education at that time). It became a kind of compromise between the versions of writing used in “Greater Ukraine” and Halychyna. It was decided to write original words according to the pronunciation of Central and Eastern Ukrainian dialects and loanwords as they were written in Halychyna.

Why did the Soviets resort to korenizatsiya?

The Bolshevik government addressed the nations in their language to gain their understanding and approval. The Bolsheviks did this to make the peoples of the union republics accept them as their friends, not invaders. Therefore, Ukrainization was a means, not a goal. The goal was to strengthen the power of the Bolsheviks.

So after Ukrainization ended, bans and repression began?

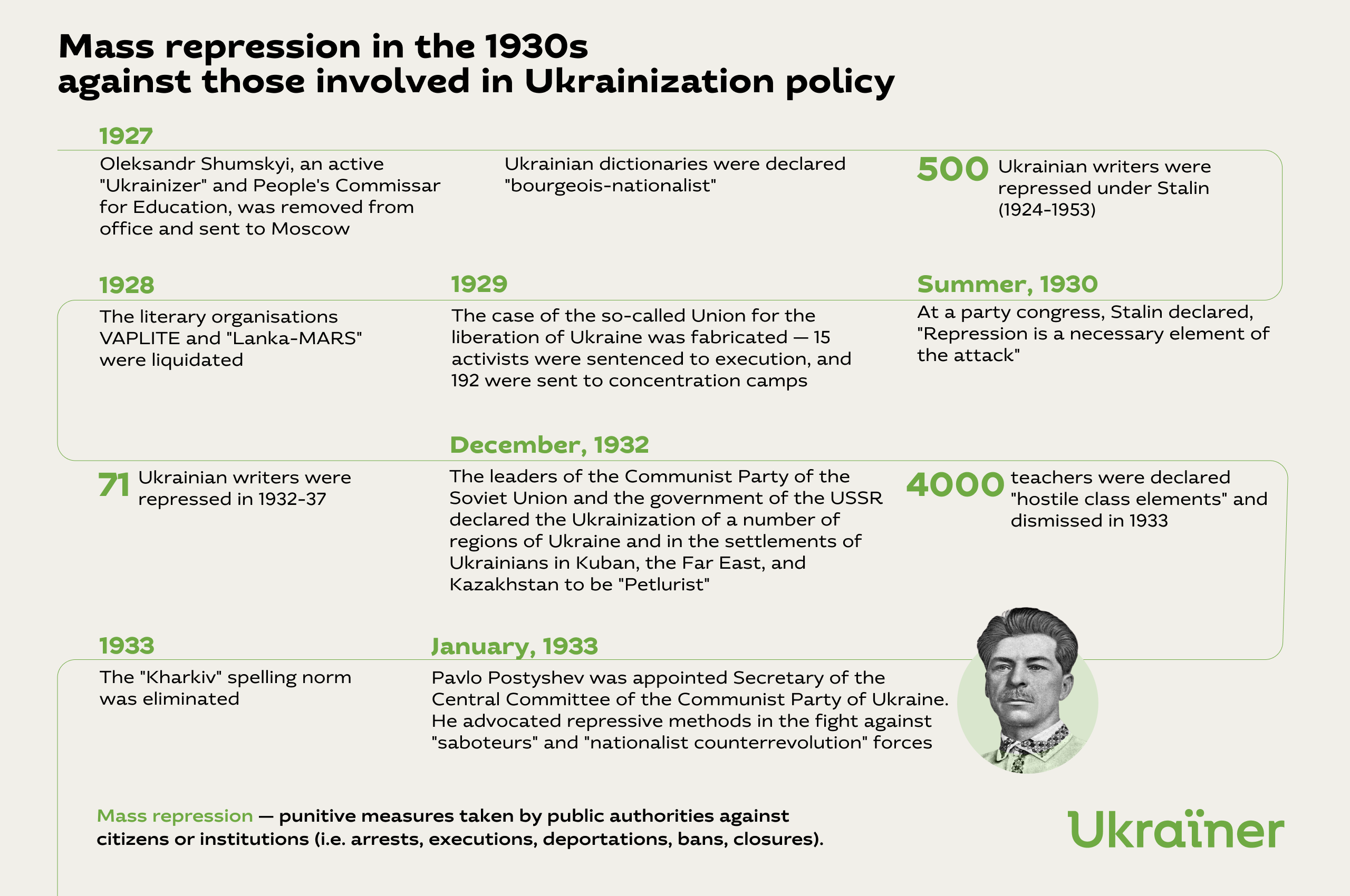

Yes, in 1932 (the beginning of the Holodomor) the policy of korenizatsiya began to be curtailed. Ukrainization was declared “Petliurist” (after Symon Petliura, a Ukrainian politician who actively opposed Bolsheviks and was on their wanted list). Many philologists, writers, playwrights, directors, and scientists were imprisoned, sent to concentration camps, or executed.

In 1933, the spelling commission abolished the norms of the “Kharkiv orthography” of 1927-1928. They declared them along with the newly compiled dictionaries to be “bourgeois-nationalist”. The authorities began to work on new dictionaries designed to “remove artificial barriers between the Ukrainian and Russian languages” and to “reflect the beneficial effect of the Russian language on Ukrainian”. Also, the Soviet authorities believed that it was necessary to develop a “common vocabulary of the languages of the USSR’s peoples” and to widely introduce internationalisms.

Now the Soviet government began to interfere with the internal mechanisms of the language: it was forbidden to use certain words, syntactic constructions, and grammatical forms. Instead, they introduced the words that were closer to Russian or even calques. They removed the vocative case, the use of the Ukrainian polite addresses: пані, добродійко (lady); пане, добродію (sir). They even removed the letter ґ from the Ukrainian alphabet, although, for example, this letter occurs in more than 300 words in Hrinchenko’s dictionary (1907-1909).

There were also restrictions on the level of use of the Ukrainian language, for example, in science. In 1970, the Ministry of Education of the USSR issued an order requiring that dissertations be written and defended exclusively in Russian.

Of course, the spread of the Russian language in Ukraine was also facilitated by the Soviet resettlement policy. During the Soviet era, many Russians and individuals of other nationalities were relocated to the territory of the Ukrainian SSR. They could not use their national languages, and they used Russian instead.

What was the language of instruction in schools, colleges, and universities in Soviet times?

On April 20, 1938, the resolution of the Council of People’s Commissars of the Ukrainian SSR and the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine “On compulsory study of the Russian language in non-Russian schools of Ukraine” was issued. In 1959, the Verkhovna Rada of the Ukrainian SSR passed a law “On the strengthening of the connection between school and life and the further development of the public education system in the Ukrainian SSR “. According to the new law it was not mandatory to study the Ukrainian language in schools. The result can be illustrated by a scene from a biographical film “Forbidden” (Ukraine, 2019). The scene includes a school in Horlivka in Donetsk region, where the Ukrainian language and literature are taught by Vasyl Stus, who later becomes a famous Ukrainian poet. A mother is making a request — she wants the Ukrainian language to be removed from her daughter’s studies. The daughter is a student who the teacher praises for her diligence and talent. The woman thanks the teacher, says sorry, and explains that it is better for her daughter to learn Russian to make her life easier. It turns out that this is the second language class refusal in a week. It is about 1963, and the situation fully complied with the 1959 law. People rejected Ukrainian because they considered it dangerous and hopeless, in contrast to Russian.

Almost all middle-level educational institutions (training schools), except for cultural and pedagogical, were Russified. At the universities of Dnipropetrovsk, Kharkiv, Odesa, and Donetsk, teaching at all departments except the Ukrainian philology department was conducted in Russian. Russian was used for teaching in polytechnic, industrial, medical, trade, agricultural, and economic educational institutions. Some western regions were the exceptions.

That is why in Ukraine, some people have never studied the Ukrainian language in schools, nor have read Ukrainian books and newspapers, nor have watched Ukrainian films.

Did Ukrainians reconcile with the Russification policy, or did they still protest against it?

Even in the darkest times of Stalin’s repression, there were voices protesting against Russification. There were many protests both at that time and after Stalin’s death. Here are just a few examples.

In 1939, Maksym Rylskyi wrote in “Literaturna hazeta” (Literature newspaper), “The system of decrees, prohibitions, and restrictions, the system of administration cannot be useful for the development of language culture”. By the way, Maksym Rylskyi was also repressed and imprisoned, but was not sent to a concentration camp. In 1969-1970, Borys Antonenko-Davydovych, in the newspaper “Literaturna Ukraïna” (Literary Ukraine) and the magazine “Ukraïna”, raised the question of returning the letter ґ to the Ukrainian alphabet along with a number of previously removed words and forms. At that time he had already spent more than 10 years in prison and concentration camps. Ivan Svitlychnyi openly criticised the 1948 Russian-Ukrainian dictionary on the pages of magazines for Russifying the Ukrainian language, and then he even worked on a dictionary of synonyms in the concentration camp. However, he was not able to complete it due to difficult living conditions which led to illness and a premature death.

In 1959, when the law “on strengthening the connection between school and life and the further development of public education in the Ukrainian SSR” was passed, according to which Ukrainian could not be studied in schools, Ukrainian poets Mykola Bazhan and aforementioned Maksym Rylskyi argued against this law in the press. Pavlo Tychyna, then chairman of the Verkhovna Rada of the Ukrainian SSR, resigned not wanting to participate in the vote. Oles Honchar and Andrii Malyshko, who were deputies of the parliament of the Ukrainian SSR, wrote a joint statement of protest against the adoption of the law.

In 1965, Ivan Dziuba wrote a book with a title that rhetorically asked: “Internationalism or Russification?”. The authorities declared the book anti-Soviet and its possession and distribution a criminal offense.

In 1978, Oleksa Hirnyk committed an act of self-immolation in protest against the Russification of Ukraine. Before that, he had been distributing handwritten leaflets for four years, speaking out against the Russian occupation and Russification.

At the place of Oleksa Hirnyk self-immolation act at Chernecha Hill. Source: online media Istorychna Pravda www.istpravda.com.ua.

Resistance was provided, in particular, by those who, it seems, were not persecuted by the Soviet government, but as it seemed at first glance, were kindly treated. For example, in the 1940s-1950s, texts such as Oleksandr Dovzhenko’s script Ukraine in Flames and Volodymyr Sosiura’s poem “Love Ukraine” were published. They became almost political manifestos in literary disguise. Or, for example, the world’s first cybernetic encyclopedia was published in Ukrainian. How did it happen? It was important for the scientist Viktor Hlushkov, one of the first computer scientists in the world, to publish an encyclopedia of cybernetics — to spread science. And for the writer Mykola Bazhan, who held high government positions in the Ukrainian SSR for many years, it was important that the encyclopedia be published in Ukrainian. Bazhan managed to convince Hlushkov that the first edition should be published in Ukrainian — they said it would be a trial, and then, upon editing, it would be published in Russian. In 1973, the encyclopedia of cybernetics was published in two volumes in Ukrainian.

How did the language situation change after Ukraine gained independence?

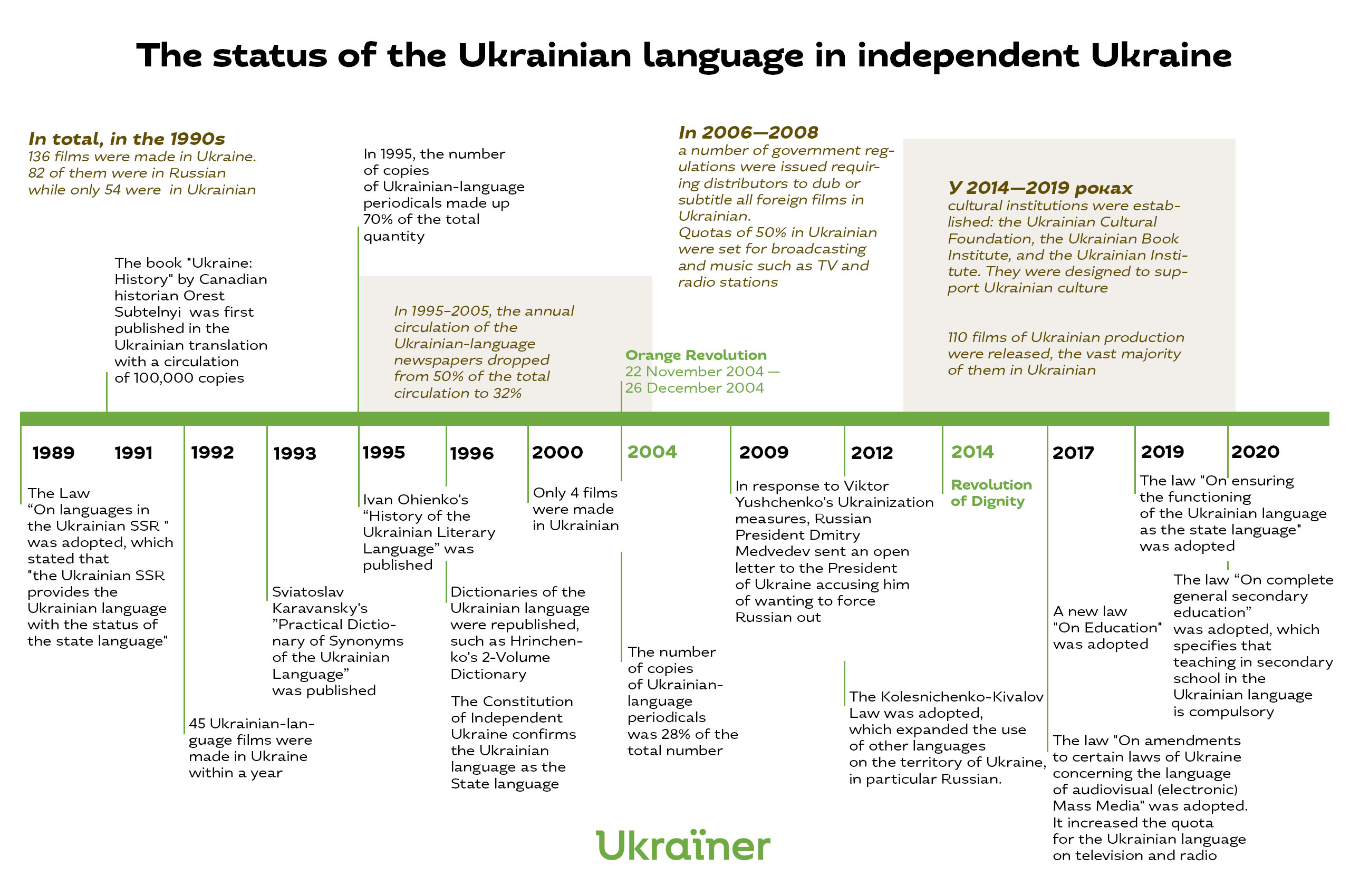

Two years before independence, in 1989, when the Soviet Union was undergoing “perestroika”, the Law on languages in the Ukrainian SSR was passed, stating that “the Ukrainian SSR gives Ukrainian the status of a state language”. This status was specified in the Constitution of independent Ukraine (1996).

However, after many years of colonial rule, the situation developed inertially, and diglossia which had lasted for centuries, did its thing.

Diglossia

The functioning of two languages in one society, but in different spheres: for example, one language in politics, education, science, public use, and another language in everyday life or folklore performances. Therefore, one language is perceived as "more prestigious” or “higher", and the other as “less prestigious” or “lower".On the one hand, interest in the history of Ukraine grew. For example, Ukraine: A History by Canadian historian Orest Subtelnyi was first published in Ukrainian in 1991 with a circulation of 100,000 copies. Further, despite the disappointing economic situation of the 1990s, books by philologists who were repressed or deliberately forgotten in the Soviet Union were published. These books included Sviatoslav Karavanskyi’s “Practical Dictionary of Synonyms of the Ukrainian Language” (1993), Ivan Ohienko’s “History of the Ukrainian Literary Language” (1995), and dictionaries of the Ukrainian language such as Hrinchenko’s Dictionary in 2-Volumes (1996). Words banned in Soviet times began to return to use.

On the other hand, there was no balanced language policy that would help overcome diglossia, and Ukrainian continued to lose to Russian in many areas. The number of schools with Ukrainian as the language of instruction was growing. The number of hours for studying it increased. Admission campaigns in universities were conducted in the state language. The Ukrainian language exam became mandatory. These were all important achievements. However, in the media — Russian dominated. Branches of Russian mass media were opened in Ukraine.

Although interesting Ukrainian-speaking performers, such as Katia Chilly, Yurko Yurchenko, Viktor Pavlik, the groups VV, Skriabin, Okean Elzy, and others appeared on the music scene, Russian remained a more prestigious language in show business. Publishing books in Ukrainian has long been a matter of enthusiasm rather than a real business, and the domestic market was not protected or promoted at the state level. Again, books were imported from Russia without hindrance. They were cheaper than Ukrainian ones due to their larger circulation. In this case, the prime cost of each book is lower. Likewise, Russian-made films and Russian TV channels were broadcast without hindrance. Films from other countries were dubbed into Russian or Russian-dubbed products were bought in Russia.

After the Orange Revolution, there were some changes, primarily in the field of media. Quotas were set at 50% for broadcasting and music in Ukrainian on all TV and radio stations. In 2006-2008, a number of government decrees required distributors to dub and/or subtitle all foreign films in Ukrainian.

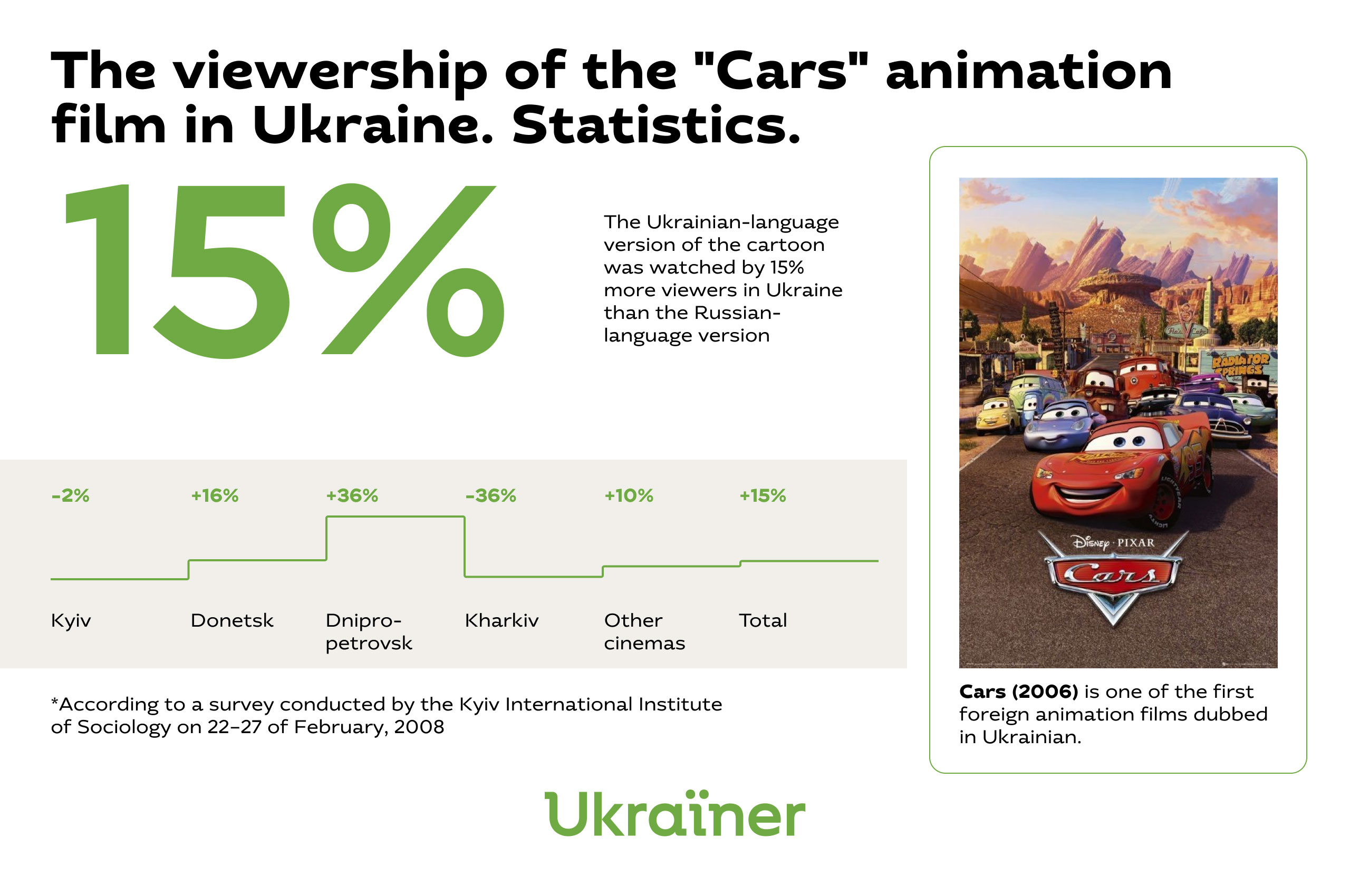

Despite the controversy over whether Ukrainian-language films could be mass-produced, people across the country continued going to cinemas after regulations on the mandatory dubbing/subtitling of films in Ukrainian had been introduced. According to a survey by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, only 3% of citizens said that Ukrainian dubbing prevented them from going to the cinema, and the first Ukrainian dubbed animation film “Cars” (2006), shown in two versions — Ukrainian and Russian — revealed that the Ukrainian version was watched by 15% more viewers than Russian. In particular, a larger number of viewers watched this movie in Ukrainian in Donetsk region, where the Russian-speaking majority prevail.

It should not be forgotten that Russia was deliberately influencing the language situation in Ukraine all this time. One of the vivid examples is that in 2009, in response to Viktor Yushchenko’s Ukrainization measures, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev sent an open letter to the President of Ukraine accusing him of wanting to oust the Russian language from the media, science, education, and culture.

Under the pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych, attempts were made to overturn the preceding president’s achievements in terms of language. These attempts included a decision to replace mandatory dubbing of films in Ukrainian by a resolution on mandatory dubbing of films in Ukraine (no matter what language), and mandatory subtitling of films in Ukrainian if the film is dubbed in another language. At that time, the so-called Kolesnichenko-Kivalov Law (Law on the principles of state language policy № 5029-VI 2012) was also adopted, which expanded the use of other languages in Ukraine, primarily Russian in practice.

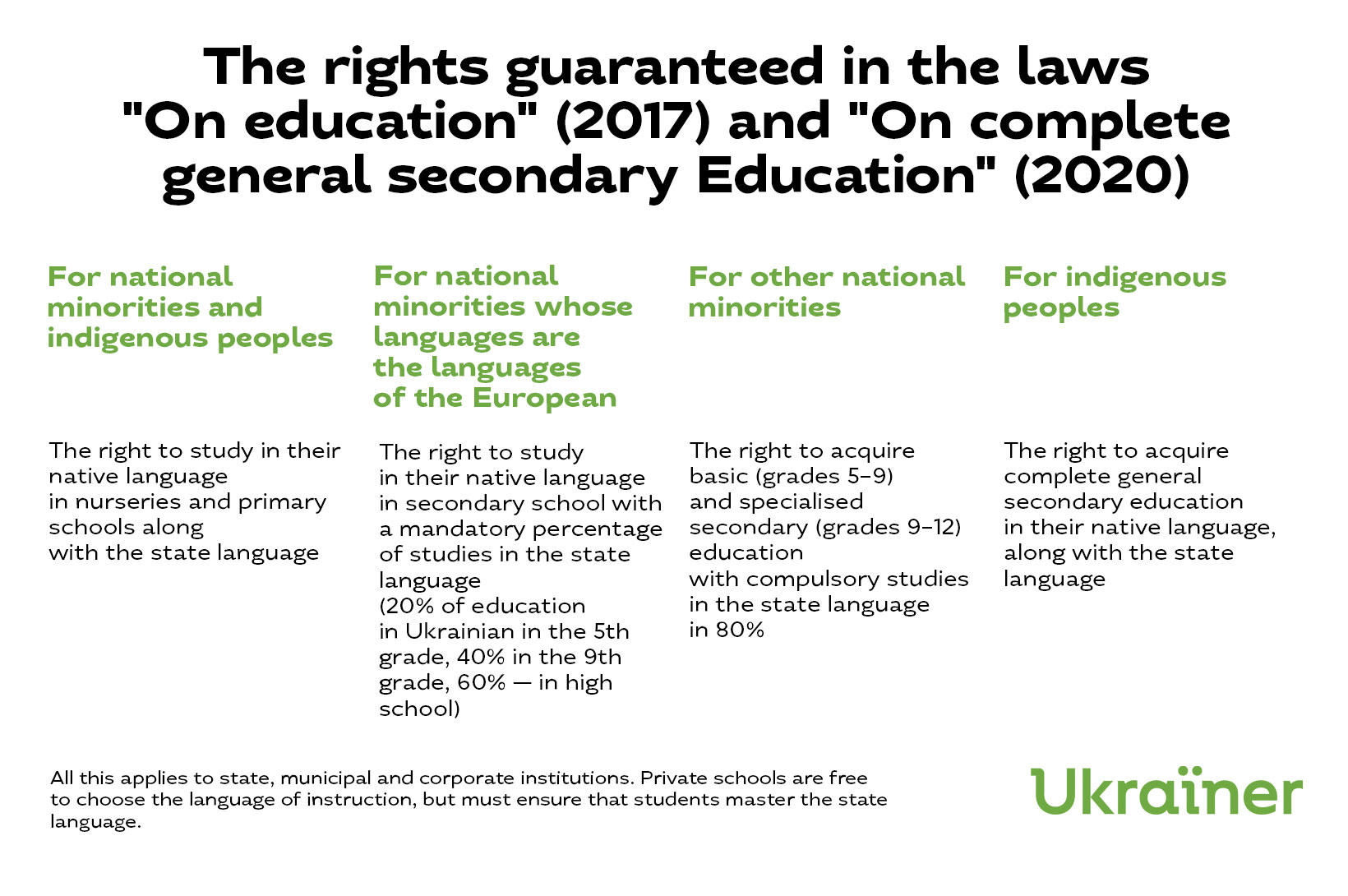

The period from 2014 to 2019, after the victory of the Revolution of Dignity, can be called a new round of Ukrainization. Significant changes started to take place in a key area of language use — education. In 2017, a new law “on education” was adopted. Until then, in Ukraine they studied and taught according to the law adopted before the proclamation of Independence, in May 1991. In March 2020, the Law of Ukraine “On Complete General Secondary Education” was passed. It mandates teaching in Ukrainian in secondary school.

The law stipulates that all students who finish school (Year 12) must be fluent in the state language.

In 2019, the Law of Ukraine “On Ensuring the Functioning of the Ukrainian Language as the State Language” was finally adopted. Immediately after its articles came into force, there was an increase in the use of Ukrainian in the public sphere including in the Verkhovna Rada and in local governments. The service sector has also seen striking changes.

In addition, during this period, in 2014-2019, cultural institutions were established: the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation, the Ukrainian Book Institute, the Ukrainian Institute. All of these institutions were designed to support Ukrainian culture, to replenish it with new models, and to promote it. Significant funds were invested in the development of cinema and other creative industries during this period. This is evidenced, in particular, by the fact that in 2014-2019 a hundred and ten films of Ukrainian production were released, the overwhelming majority of them — in Ukrainian.

Has the language changed since Independence?

Of course. Slang changed, as by definition it changes every few years in all languages. There were also neologisms to denote new phenomena. In the 1990s, certain words banned or deliberately forgotten in Soviet times began to return to use.

At the same time, the rejection of Russianisms imposed on the Ukrainian language and widely used earlier began.

And, of course, since English is the dominant language in the world today, Ukrainian is replenished with Anglicisms every day. Loanwords acquire Ukrainian affixes.

Should we give up all words similar to Russian?

No, not at all.

Because of the previously implemented Russification policy, some people really want to give up everything that looks like Russian. So they start avoiding words similar to Russian. Actually, Ukrainian and Russian are related, and apparently, their vocabularies are similar. Self-sufficiency is not about fighting anything that sounds different, it is about speaking Ukrainian without looking at neighbouring languages.

In addition, words that do not sound similar to Russian are not always more specific to Ukrainian. For example, the Ukrainian word “dakh” (roof) was actually borrowed from the German word “Dach”. However, the Russian word for roof, “krysha”, which is still widely used, although generally perceived as a Russianism, is a common Slavic word derived from the root “kryty” (to cover). There have been dozens of processes that triggered changes in words and meanings. There are even more words that are similar to Russian, but in fact, they are not.

Does adopting loanwords clutter up the language?

Lexical borrowing is a natural phenomenon in all languages whose speakers are in regular contact with

foreign speakers. The territory where the Ukrainian language is spoken has always bordered on and was in close contact with the iconic cultures of its period and region. This has significantly affected the language Ukrainians speak today.

Loanwords often come into a language in waves and can fill a certain area of use. For instance, before the Old Ukrainian language appeared, Proto-Slavic was replenished by loanwords from German in the military-political and domestic spheres, such as words for prince, helmet, king, sword, regiment, well, carrot, and radish. Later, in the 13th-14th centuries, Ukrainian was filled with Germanisms that were used in the field of handicrafts and trade, like the words for locksmith, furrier, wheelwright, fair, and account.

In the 11th century, a lot of Greek words used in the religious and ecclesiastical sphere came into Ukrainian (mainly through the Old Slavonic): for example, words for angel, apostle, Bible, icon, and many others, including calques. In the 16th-17th centuries, when the ancient Greek language was studied in schools, many Greek words denoting school terms came into Ukrainian, such as words for mathematics, philosophy, vocabulary, syntax, drama, theater, and choir. Of course, antiquity and Christianity made up the basis for European civilization, and therefore, Greek words and Latinisms fill European languages and are exchanged between them, already modified. In particular, ancient Greek and Latin are present in most words from science, technology, politics, and culture in many languages.

Close contacts with the steppe brought Turkic loanwords. In the times of Kozaks, Ukrainian was filled with even more Turkish words due to close connections with Crimea, for example, words for watermelon, pumpkin, cauldron, carpet, and barn. A lot of terms from a traditional Kozak vocabulary, including kozak itself, were in fact Turkish.

Yiddish became one of the major languages in terms of its impact on the formation of Ukrainian. There was a two-way exchange: on the one hand, words denoting such concepts as borsch, Kozak (distorted by French into Cossack), and steppe passed from the Ukrainian language into the European ones through Yiddish. That is why in Europe they say “borscht”, not “borshch”, because this word is pronounced this way in Yiddish. From Yiddish, Ukrainians borrowed the words for purse, swindler, iron, porch, shout, and, most importantly, under the influence of Yiddish, the sound ґ /g/ was returned to the Ukrainian language. Long ago, at the very beginning of its development, this Proto-Slavic sound almost disappeared from the Ukrainian language, remaining a corresponding lenis consonant to the fortis k. Then the sound ґ returned to Ukrainian in loanwords from Yiddish, German, and some other languages. Meletius Smotrytsky, creating his grammar, borrowed a letter to convey this sound from the Greeks.

At the same time, Ukrainian was filling up with loanwords from many western neighbours: Polish, German, Hungarian, Romanian, and other languages.

It’s not hard to guess from which language Ukrainian borrows the most words today. This is the language that currently affects most of the world’s languages. Business, education, technology — all these industries are full of English words. Smartphone, cashback, creative industries, crowdfunding, online commerce, event, IT cluster, blockbuster, all sound almost the same in Ukrainian. Not all of them have entered the literary language, and not all will enter. It has already been mentioned that lexical borrowing is a natural phenomenon; however, sometimes speech that teems with newly arrived words may be hard to understand. That is why it makes sense to look for equivalents based on specific Ukrainian words or roots borrowed long ago, which Ukrainians often do. This way, there are original Ukrainian words to denote crowdfunding, leader etc. as well as extracted from the depths of the language, like words meaning airport, deadline, environment, and photo.

Did Ukrainian “lend” its words to other languages?

Of course, certain words have passed from the Ukrainian language to others. First of all, these include exotic words representing purely Ukrainian realities, such as borsch, varenyks, hryvnia, vyshyvanka, bandura, and, what is especially interesting, Maydan. Why is it so interesting? The word maydan was borrowed from Persian through Arabic and Turkic. However, due to significant political events in the history of Ukraine — the Orange Revolution and the Revolution of Dignity, which Ukrainians call the Maydan, — this word is associated by foreigners with Ukraine and denotes revolutions that have taken place there. In addition, there are some words that are considered loanwords from Ukrainian in Polish, Russian, Hungarian, and Romanian.

Should we despise dialects and zealously fight for the purity of language?

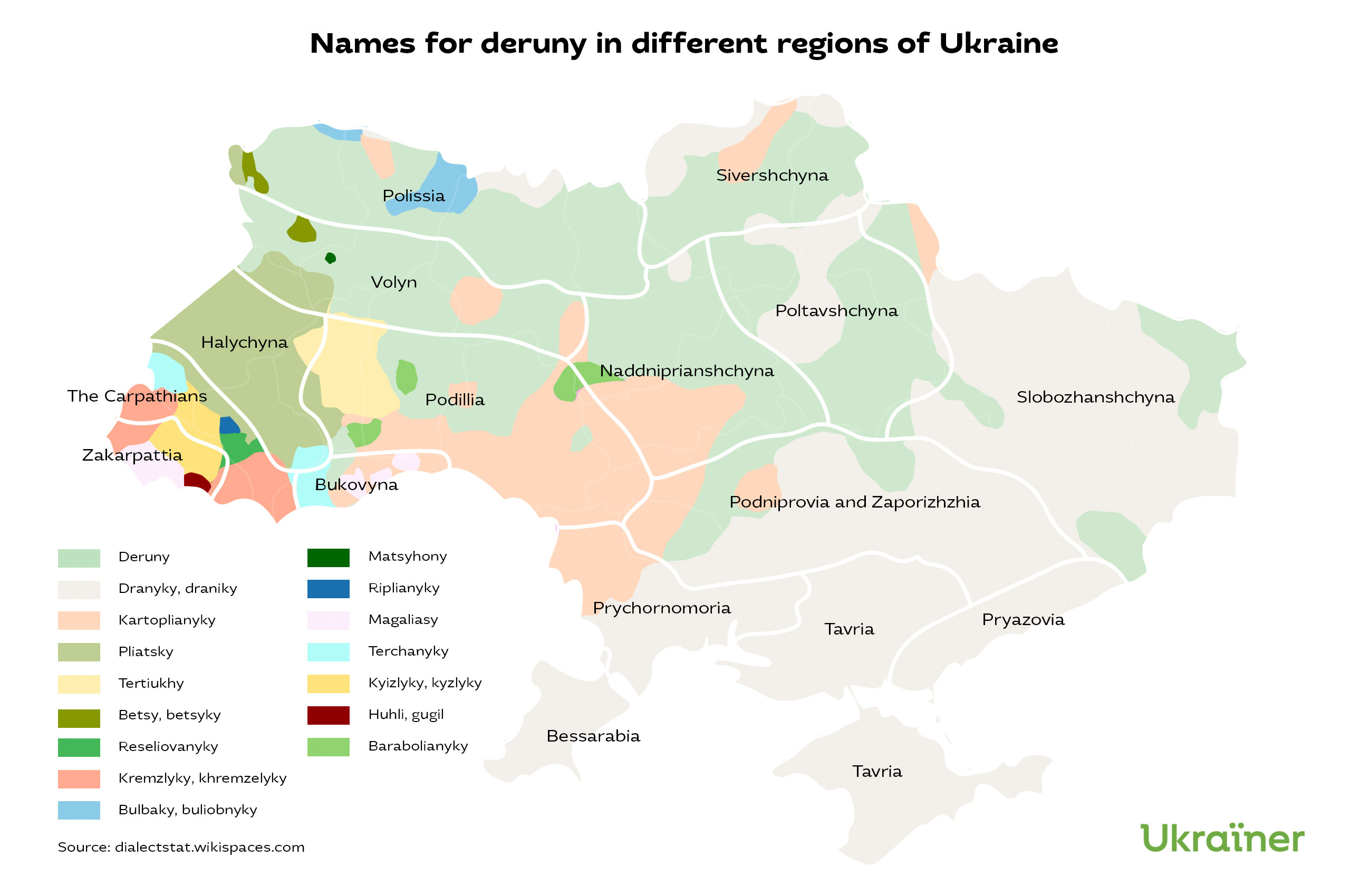

The concept of purity of language is relative because literary language is a matter of agreement: philologists have decided to consider certain words and forms correct and others incorrect. The literary language itself comes from dialects — as it has been already mentioned, the Ukrainian literary language is based on the Kyiv-Poltava dialect, or the Middle Dnipro subdialect, but it was significantly influenced by other dialects, including the Dnister subdialect.

In general, from a scientific point of view, dialects include jargon and slang (it is then called a social dialect or sociolect). This section is about the regional dialect, or, in other words, the peculiarities of speech in different regions.

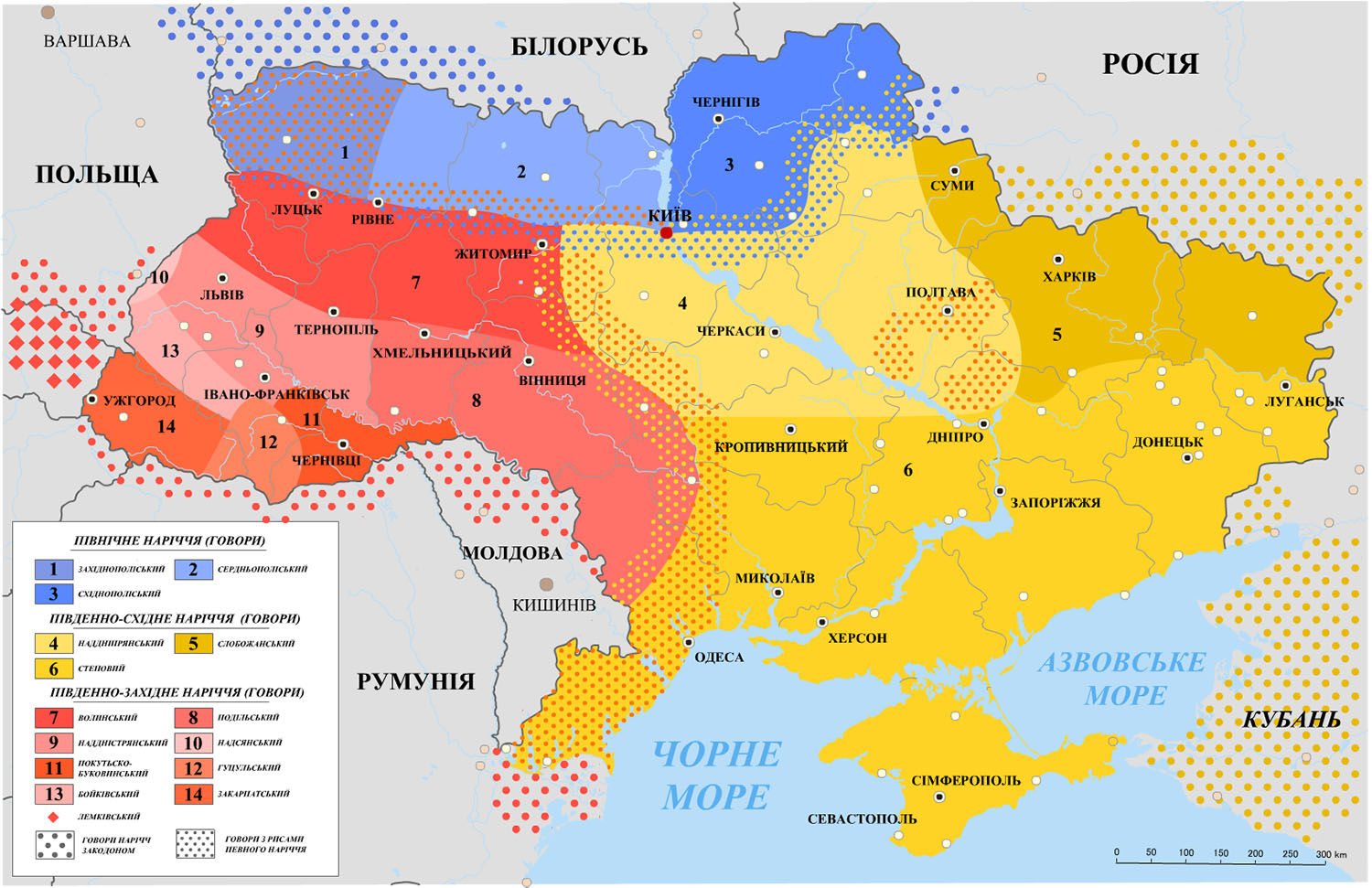

Scholars divide the Ukrainian language into three dialects: northern (or Polissia), southwestern, and southeastern. Dialects are subdivided into subdialects (only 15 subdialects within three dialects). Within the subdialects, there are multiple varieties (each village and city has its own one). Lastly, everyone has their own idiolect.

A map of Ukrainian dialects and subdialects. Source: Wikipedia.

The most archaic features are preserved in the northern dialect. Just imagine: in the villages in the north of Chernihiv region or in Kyiv region you can sometimes hear sounds or words that were used before the times of Kievan Rus!

However, many archaic features are also preserved in the dialects around the Carpathians, for example, in the Hutsul and Zakarpattia dialects.

It is often believed that certain words live in the dialects of certain regions because they are borrowed from neighbouring languages. Sometimes this happens, for example, in Zakarpattia, they call the city “varosh” because it sounds so in the neighbouring Hungarian: város. In Bessarabia, the Romanian word for corn is used. But it often happens that a word or form existed in a particular area long before borders were established, and this area started to belong to two different states. The word or form was preserved in the literary language of one state and replaced with another form in another state remaining in the dialect.

Why does the language of the diaspora sound so… different?

As early as the middle of the 18th century, the entire North-Eastern Presov region and Zakarpattia communities moved to the Balkans, fleeing poverty and landlessness.

From the 1870s until the beginning of the First World War, Ukrainians traveled en masse to North and South America, and to Siberia. During the twenty years between the wars, they emigrated again to the United States and Canada, but often to European countries. After the Second World War, Australia and New Zealand were added to this list.

Svoboda (Freedom) — a newspaper of Ukrainian diaspora in the USA. Source: The newspaper’s archive.

Imagine the language of the late 19th century to the first third of the 20th century. If a Ukrainian met a school teacher from Halychyna of that time, they would understand each other, of course, but many words would be unfamiliar to a modern Ukrainian, and even if the words were familiar, their pronunciation might be surprising.

And that is the language which Ukrainians, whether from Halychyna or Greater Ukraine, brought to the new places. In Ukraine, the language has changed in one direction: Sovietization, de-Polonization, Russification. There was not only a complete transition to Russian, but there was the replacing of certain words in Ukrainian to versions closer to Russian, and new realities specific for this area influenced the language, which could not appear within Ukrainian communities in Germany or America because the realities were different. As a result, on the one hand, the language of emigrants was frozen, preserved, and, on the other hand, supplemented by loanwords from the local languages. Therefore, it seems to Ukrainians that the diaspora’s language is funny, while the diaspora thinks that Ukrainians are completely Russified, although, in fact, foreign Ukrainian is full of archaisms and contains a handful of loanwords that make it different from the Ukrainian language that is spoken on the territory of Ukraine.

How was the mixed language — surzhyk — born?

Russian and Ukrainian, as neighbouring languages, undoubtedly influenced each other. In Russian, there are many Ukrainianisms; however, from the beginning of the 18th century, Russian began to influence Ukrainian due to special circumstances: the language of the empire became the language of the colony. Ukrainians who became tsarist officials or soldiers adopted the Russian vocabulary. When the Russian administration began to function in Ukrainian cities, Russians arrived in Ukraine in large quantities, which also affected the speech of local residents. Diglossia was established in Ukraine. Russian was used in government, education, and culture, while Ukrainian was used in everyday life.

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, two-thirds of the townspeople in Greater Ukraine were Russians and Russified Jews owing to the resettlement policy. The vast majority of peasants were Ukrainians. When industrialisation began and peasants moved en masse to the city, they switched to a more common language, and the opposition emerged: Ukrainian was the language of the village, and Russian was the language of the city. These peasants did not speak Russian well because it was different, so Ukrainian and Russian were mixed. This is how the mixed language — surzhyk — was born.

Diglossia in the Ukrainian lands was exceptionally distinct during the 19th and 20th centuries. After Ukraine gained Independence, the Russian language did not disappear, as Russians and Russified Ukrainians continued to communicate in Russian as a “more prestigious” language or just out of habit. In addition, Russian continued to fill media: television, radio, newspapers, and magazines. Many of these media were, in fact, from Russia — in the 1990s, most Ukrainians still watched ORT, RTR, and other TV channels governed from Moscow. Therefore, the conditions for surzhyk were favourable: the local Ukrainian language mixed with the local Russian was actively mixing with Russian from Russia.

Today, when Ukrainian has become the language of public administration, education, science, and most of the media, it is more and more a “prestigious” language, while surzhyk is still the type of speech of the uneducated. However, the experience of other countries that came out of the colonial situation and mixed speech types suggests that the more Ukrainian language will be in public use — in the media, education, government, service — the less space will be left for surzhyk.

Why do some writers or other educated people write their posts on social networks in surzhyk?

Surzhyk is also often used in a humorous way. It is almost absent in the media but can often be found on social networks, in humorous posts. Educated Ukrainians — often writers, editors, journalists, translators — speak and write posts in surzhyk (although, of course, they speak a literary language), as if inviting their readers to a kind of “circle of trust”. Many people grew up with surzhyk, and surzhyk can be associated with home. Surzhyk sometimes creates an atmosphere of homeliness, comfort, and trust. Books written entirely in surzhyk, such as Mykhailo Brynykh’s Masterpieces of Ukrainian literature and Masterpieces of world literature, came from the same jovial mood. Of course, this is not the language we can hear on the suburban train — it is filled with terms, anglicisms, but it is still surzhyk. You can read more about surzhyk in literature in the explanatory article about Ukrainian literature.

Is surzhyk a separate language or dialect?

No, it’s not.

Some words that look like they belong to surzhyk are in fact elements of a dialect. But surzhyk itself is neither a language nor a dialect because both languages and dialects have their norms, even if they are not established spontaneously and are not codified. On the other hand, surzhyk has no norm — a person spontaneously chooses words from one or another language.

Many Ukrainians switched to Russian due to the political situation. And were there those who switched from Russian or other languages to Ukrainian?

There are many such examples. A Russian Mariia Vilinska studied Ukrainian and became a Ukrainian writer, pen name Marko Vovchok. Hryhorii Kvitka-Osnovianenko wrote plays in Russian in the 1820s and 1830s, but in the late 1830s, he began writing in Ukrainian and was an “advocate” for the artistic possibilities of the Ukrainian language. Olena Kurylo, who came from a Jewish family, became a prominent Ukrainian philologist and was subjected to Stalin’s repressions. Although Oleksandr Oles belonged to a Ukrainian family, he did not constantly speak Ukrainian; he decided to switch to it completely at the unveiling of the monument to Kotliarevskyi in Poltava, where he met Panas Myrnyi, Lesia Ukrainka, and other cultural figures. As a child, Olena Teliha spoke mostly Russian in her family, but when one of the Russian monarchists called her second language, Ukrainian, “a dog’s language,” she strongly opposed it and became uncompromisingly Ukrainian-speaking.

Unveiling of Ivan Kotliarevskyi monument in Poltava, 1903. Image from the archive of Ivan Kotliarevskyi Literary Memorial Museum in Poltava.

There are interesting examples nowadays, too. Volodymyr Rafeenko, a writer from Donetsk, who wrote only in Russian until 2014, left for Kyiv after the occupation of his hometown, studied Ukrainian so that he could write fiction in it, and in 2019 published the novel Mondegreen in Ukrainian. At the presentation of the book, he told a shocking story. One of his grandmothers, who spoke pure Russian and never spoke Ukrainian, as it turned out later, was born in a village and grew up in a Ukrainian-speaking family. When she got to town, classmates laughed at her clumsy Russian. She decided to learn Russian better than all of them. And she did it, losing Ukrainian because of the feeling of shame created by the circumstances of that time. Volodymyr’s other grandmother also spoke Russian. The presence of Ukrainian in her childhood was evidenced by the fact that all her adult life, she spoke Ukrainian only when addressing her pets — cats and dogs.

When Belarusian Mikhail Zhiznevsky, who lived in Ukraine, and Armenian Sergey Nigoyan, who was born and raised in Ukraine, and read Shevchenko’s poems on the Maidan a few days before his death, died on the Maidan, it became clear once again that Ukraine is a multiethnic state: Crimean Tatars, Jews, Russians, Bulgarians, Armenians, Gagauz, Poles, and representatives of other ethnic groups who are citizens of Ukraine are all Ukrainians.

Owing to the upheavals of history, Ukrainian was not necessarily their ancestors’ language for many Ukrainians, and their family stories were different. Hopefully though, Ukrainians will continue choosing Ukrainian as the language of their children; the language not only of many generations of people who lived on these lands, but also the language of the future. And they should remember: Ukrainian-speaking Ukraine is Ukraine protected from an external enemy by its own unity.

supported by