In this text, we will find out how Ukrainian literature was formed independently and in the fight against numerous prohibitions, without which it cannot be imagined, and in general, whether the exact start date of modern Ukrainian literature is known. And we’ll look into baroque palindromes, read anecdotes about Chornobyl, listen to the sound of Ukrainian cordocentrism, and read Ukrainian intellectual novels together.

This publication is an attempt to look at the history of Ukrainian literature through the eyes of a person who would like to discover this still unknown world. This is a conversation about notable phenomena and figures that may interest a wider range of readers, and that is from a new angle to see what seems familiar. This is not a chronological statement, and it is not a canonical list of non-traditional references. It is rather a story made from colorful pieces or a guide to places that can be visited in this world.

Not exactly ancient literature

Ruthenia, or not Ruthenia

In 1187, the name “Ukraine” was first recorded in the Kyiv Chronicle, and soon, this name would be fixed everywhere. To emphasize the continuity and connection between ancient epochs and modern times, Mykhailo Hrushevskyi uses the name “Ukraine-Ruthenia.”

Modern Ukrainian tradition distinguishes between the concepts of “Ruthenia” (“Ruthenian”) and “Russia” (“Russian”). “Ruthenian” is an ethnonym of medieval Ukrainians, but in Russian and in most other languages, these concepts — “Ruthenian” (belonging to the 10th-13th centuries) and “Russian ” — are the same. Literary critic Dmytro Nalyvaiko notes that in the Middle Ages in the West, “the name ‘Ruthenian’ was assigned to Ukrainian lands altogether, while the name ‘Ukraine’ was used in the local sense as ‘Kozak land’ approximately from the middle of the 17th century.”

“Books guide us to repentance.”

In the 10th — 16th centuries, literature developed within the framework of church institutions. For the general public, books became attributed to Christianity, and the process of working on a handwritten text was likened to the sacrament of icon painting.

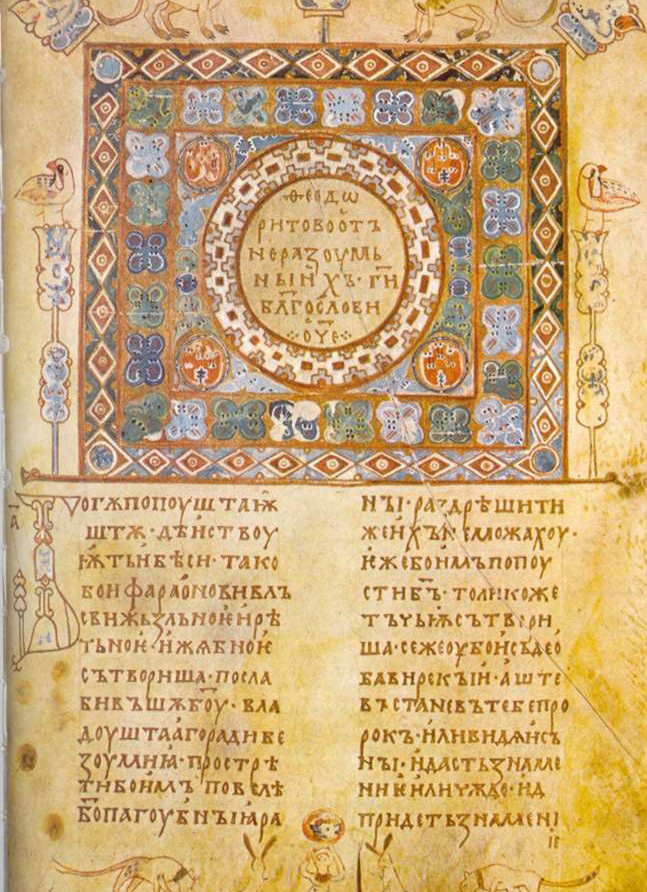

Izbornik of Sviatoslav (Sviatoslav’s Collections) (1073). Source: Wikipedia.

From the 11th century to the present, thirteen monumental works of literature have survived. For example, Izbornik of Sviatoslav (1073) was written on 266 parchment sheets and sewn into 34 books. The pages of this text collection are full of images of saints, birds, and zodiac signs.

Humiliation, shame, and passion

In the genre diversity of literature of the Kyivan Rus era, its dependence on the written or oral form of utterance is recorded.

For example, “pilgrimages” told stories about visiting holy places. The Kyiv Cave Patericon was a collection of stories about ascetic monks and their teachings.

Scribes and authors also had a special taste for the selection of names for their works that embodied their worldview systems. “Vineyard” is the word that calls the garden home and so denotes the image of the heavenly city symbolically.

The search for hidden meanings and symbols forms the basis of understanding the world. For example, Physiologus, written in the 2nd-3rd centuries in Alexandria by an anonymous author, was known in our area as early as the 12th century. In this work, stories about animals are recorded, the reality of which the scribe believes. There is a story that an elephant sleeps standing near a tree, and if it suddenly falls, it will not be able to get up on its own. Then “the big elephant” will come and try to help, but it will not. Twelve more elephants will come for him — and in vain, too. But in the end, “the little elephant” will appear, exposing its trunk and putting the poor elephant on its feet.

National Geographic can’t help you understand such twists and turns. Instead, the Bible will help. And this story should be interpreted as follows: the fallen elephant symbolizes Adam, the “big elephant” — Moses, the twelve elephants — the twelve Old Testament prophets, and the small is Christ.

The author of that time was perceived more as someone who embodies God’s will than someone who is acting according to their own beliefs or choices. At the same time, we note that the first complete handwritten translation of the Bible into Church Slavonic has been preserved since 1499.

The tale of Barlaam and Joasaph, written in about thirty languages, was translated from Greek at the beginning of the 12th century. This story is notable because, according to the investigations of many researchers, it was created based on the biography of the Buddha, or Prince Siddhartha Gautama.

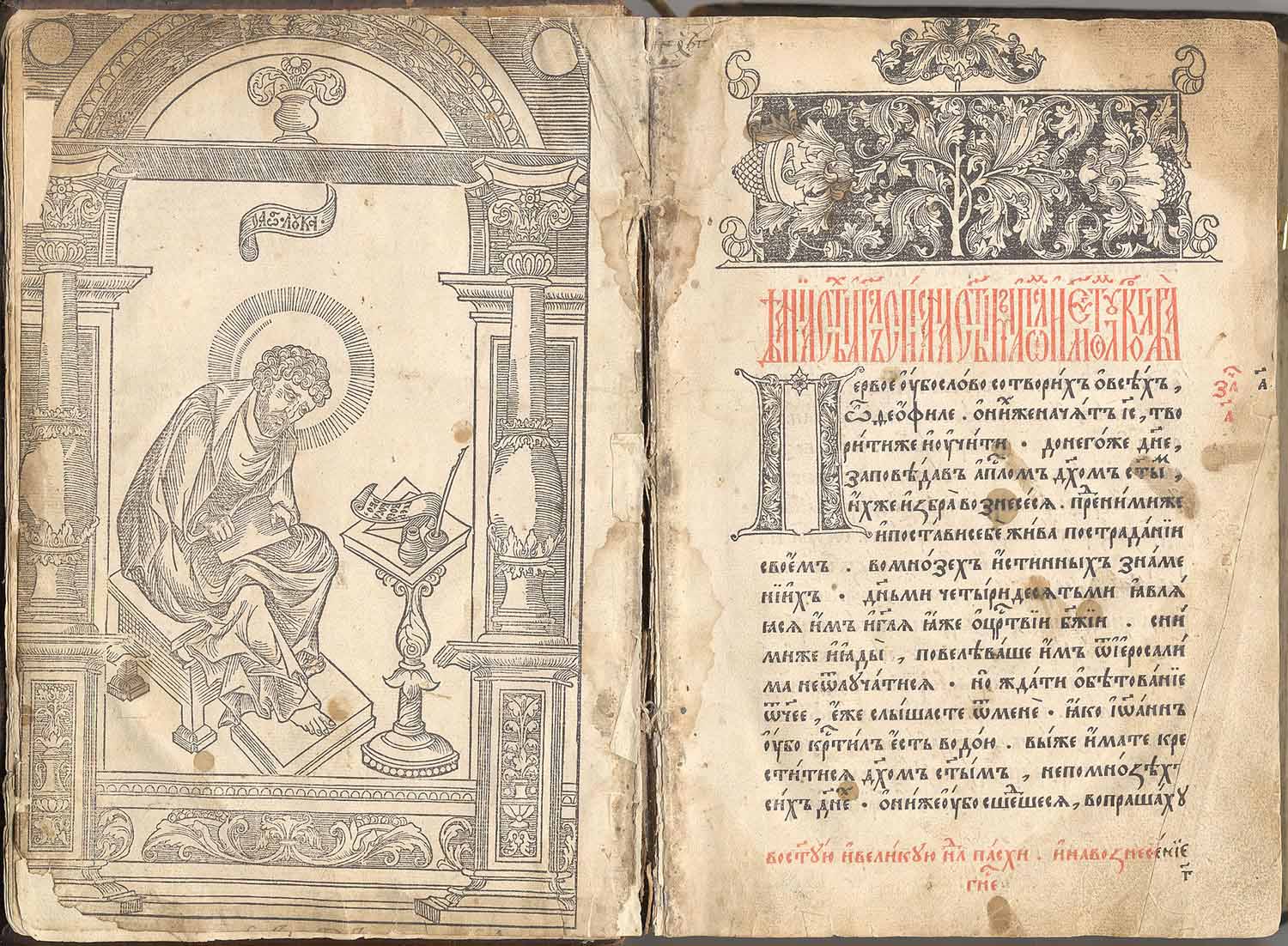

Apostolos by Ivan Fedorov. Source: Wikipedia.

But another era was already approaching: the age of printing. In 1483, the first printed book by the Ukrainian author, Yurii Kotermak, from Drohobych, was published. He was the rector of the University of Bologna, one of the most respected universities in Renaissance Europe. In 1491, the first Cyrillic publications appeared in Krakow. Around 80 years later, in 1574, Ivan Fedorovych created in Lviv the first printed book on Ukrainian lands called The Apostle and the first among the eastern Slavs called Primer.

It will be an era of artistic discoveries, strange and twisted, like a pearl in a bizarre shape.

«І О смерті пАм’ятай, і На суд будь чуткий»: Бароко3

Baroque, or not baroque

The Ukrainian Baroque is a phenomenon of the 17th-18th centuries. One of its most expressive features was the predominance of spiritual elements over secular ones. And although the form could be secular (lyrics, short stories, etc.), the content mostly had a spiritual beginning. During the Baroque period, Ukraine continued to get acquainted with its ancient heritage, which had begun in the Renaissance period, most often in a Christian-mythological context. Dmytro Chyzhevskyi gives several notable examples: “the Blessed Virgin becomes Diana”; the Cross is compared to the trident of Neptune. The attraction to grotesqueness also increases, and the game begins, a game with allegories, symbols, and shapes.

The use of the simple language is expanding, which is increasingly gaining text space from the Slavic-Ruthenian language (the Ukrainian version of the Church Slavonic language).

Catedra, matter and concept

The author of the Baroque era seeks to impress the reader and potential listener if the text is spoken publicly. Chyzhevskyi gives examples of rhetorical decorations: theatrical gestures, recitation pronunciation, calls, and appeals to Saints as if they are live persons. He appeals to them with questions and reproaches.

At the content level, we are also talking about persuasiveness and impressions. For example, Ioanykii Galiatovskyi was a monk, Archimandrite of the Yelets Monastery in Chernihiv, teacher, and rector of one of the oldest educational institutions in Eastern Europe — the Kyiv-Mohyla College. It has existed since 1632, while the Ostroh Slavic-Greek-Latin School was founded even earlier. Ioanykii Galiatovskyi called for the sermon to be interesting for parishioners. It introduced them to Christian teaching and brought some new knowledge (even about history and nature). And, by the way, preaching in the Baroque era reaches its peak. Galiatovsky used the usual Latinisms for his time — words that would resonate in the hearts of every modern person who came across curatorial concepts or filled out a grant application: affect, disposition, catedra, conclusion, concept, matter, prerogative, relation, meaning.

Age of Pearls

The Baroque is impressive. Baroque tends to surprise. Both a writer and a priest, Ivan Velychkovsky, knows exactly how. We don’t know exactly when he was born, but we have a date of death — 1701.

Velychkovsky experiments with forms. There is, for example, a unique “echo”: the following line of a poem is a word made up of the last two syllables of the last line. This poetic dialogue with Adam begins like this:

— Что плачеши, Адаме? Земнаго ли края?

— Рая.

— Чому в онь не внійдеши? Боїш ли ся брани?

— Рани.

— Не можеши ли внійти внутр його побідно?

— Бідно.

— Іли возбранен тобі вход єст херувими?

— Іми.

— Одкуду дієт ті ся сицевая досада?

— 3 сада.

— Кто ті в саді снідь смертну подаде од древа?

— Єва.

— Кто же Єву в том прельсти? Змій ли вертоградський?

— Адський.

Velychkovskyi also has palindromes (he calls them “literal crayfish”, because “they are read backwards, as crayfish walk”). There are also encrypted messages that become a continuation of his ideological instructions.

Here’s how he encrypts his name in underlined letters:

І О смерті пАм’ятай, і На суд будь чуткий,

ВЕЛьмИ Час біжить сКорО, В бігу Своєм прудКИЙ.

Not just literature

The Baroque captivates society and penetrates into various spheres. As noted by the outstanding linguist and literary critic Yurii Sherekh, the baroque “extended its general principle not only to the ‘playfulness’ of poetic jokes and the intensity of the horrors reproduced in poems, but it also increased the ornament of church carvings, the splendor of Cossack clothes, and the blatant haphazardness of speech. This haphazardness was the system’s style.”

In the 1690s, at the expense of Hetman Ivan Mazepa (who penned “Duma”), the Church of St. Nicholas was built in Kyiv. The seven-tiered iconostasis makes a remarkable impression on parishioners. St. Sophia Cathedral was being rebuilt at the expense of the Hetman and forepersons. About a dozen Baroque churches in Kyiv, including St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery, are being built or reconstructed at the cost of colonels.

Twenty years later, on April 5, 1710, Hetman Phylyp Orlyk would sign with the Cossack Foreman the document called The Constitution of Bendery.

And one more thing — historical songs and dumas were popular during the Baroque period. However, the stature of kobzar will grow in importance. The first mention of kobzars is in Polish sources from the early 1500s.

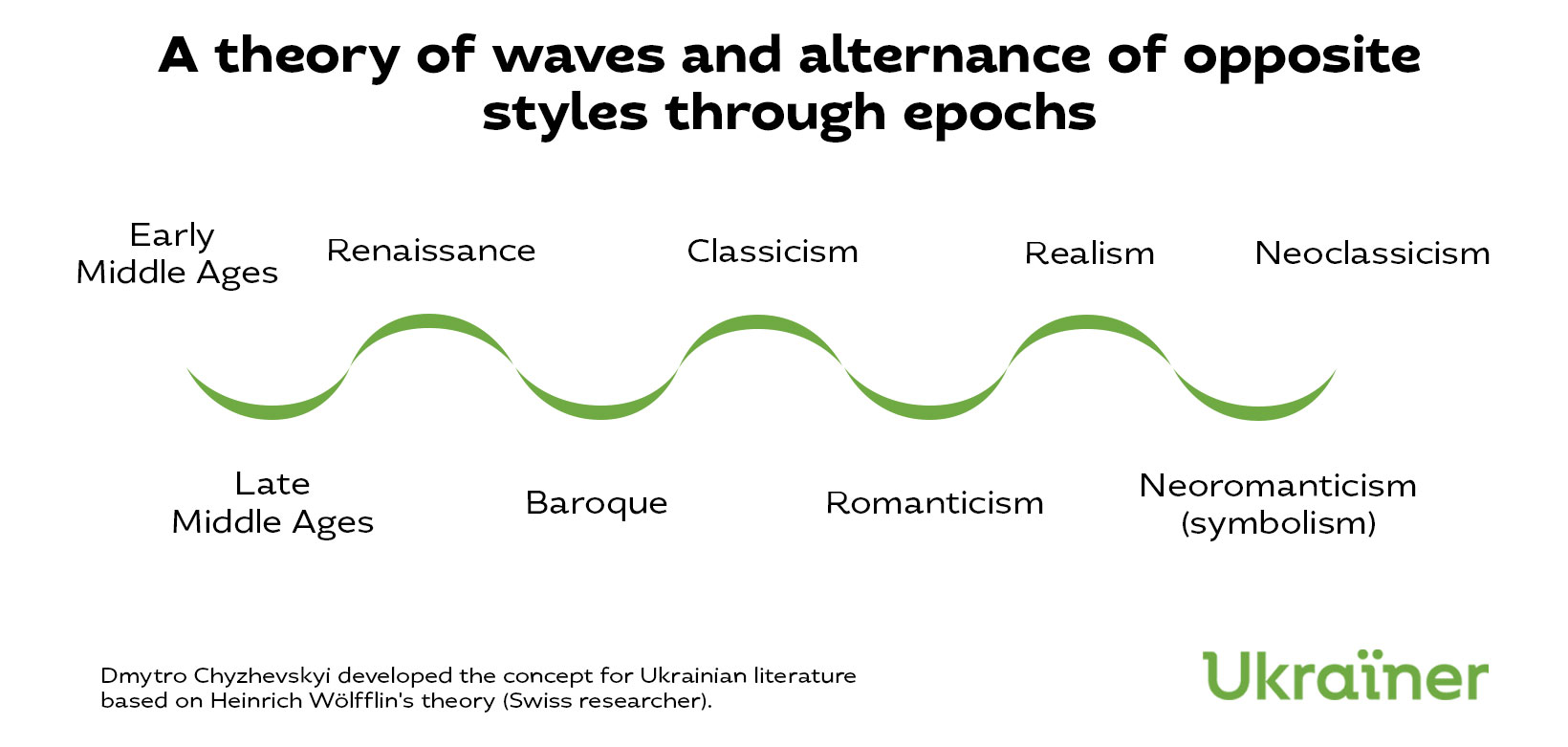

No end

The theory of waves and alternation of opposite styles of epochs, proposed by the Swiss researcher Heinrich Welflin, was developed by Dmytro Chyzhevskyi based on the history of Ukrainian literature. Welflin proposed sets of pairs of basic concepts in art history, that art history analysis relies on (among them, for example, “flatness — depth” or “clarity — ambiguity”). Chyzhevskyi continued to work with the opposition. His examples include a love of simplicity or a tendency to complexity, a desire for clarity of presentation or an emphasis on “depth”, which may not always be clear to the reader, and working with a normalized language or trying a language experiment.

D. Chyzhevskyi notes that “the scheme of development of cultural styles resembles waves on the sea: the nature of styles changes, “agitated”, fluctuating between two different types opposing each other. And from this alternation of waves of history, an essential idea for Ukrainian culture as a whole arises: each era has its own baroque style. It is invisible and indestructible”.

Hryhorii Skovoroda by V. Sizikov. Source: Central State Cinema, Photo and Audio Archives of Ukraine n.a. Pshenichny

At some point, reality craves quirkiness, craves subversive humor, craves a round of history in which you want to return to perhaps the most interesting era of your past.

Loudly, Quietly, Whispering, With your heart.

The beginning of the 18th century is marked by two events. In 1715, the first mention of the haidamaks was recorded — another archetype of Ukrainian literature and consciousness, and in 1720 a decree of Peter I was issued banning the publication of books in the Ukrainian language. Another half-century will pass, and in 1775 Russian troops will destroy the Zaporizhzhia Sich. The same year the war of independence of the North American colonies began, and 21-year-old Louis XVI was crowned to the throne of France, only to later be eliminated by the French Revolution.

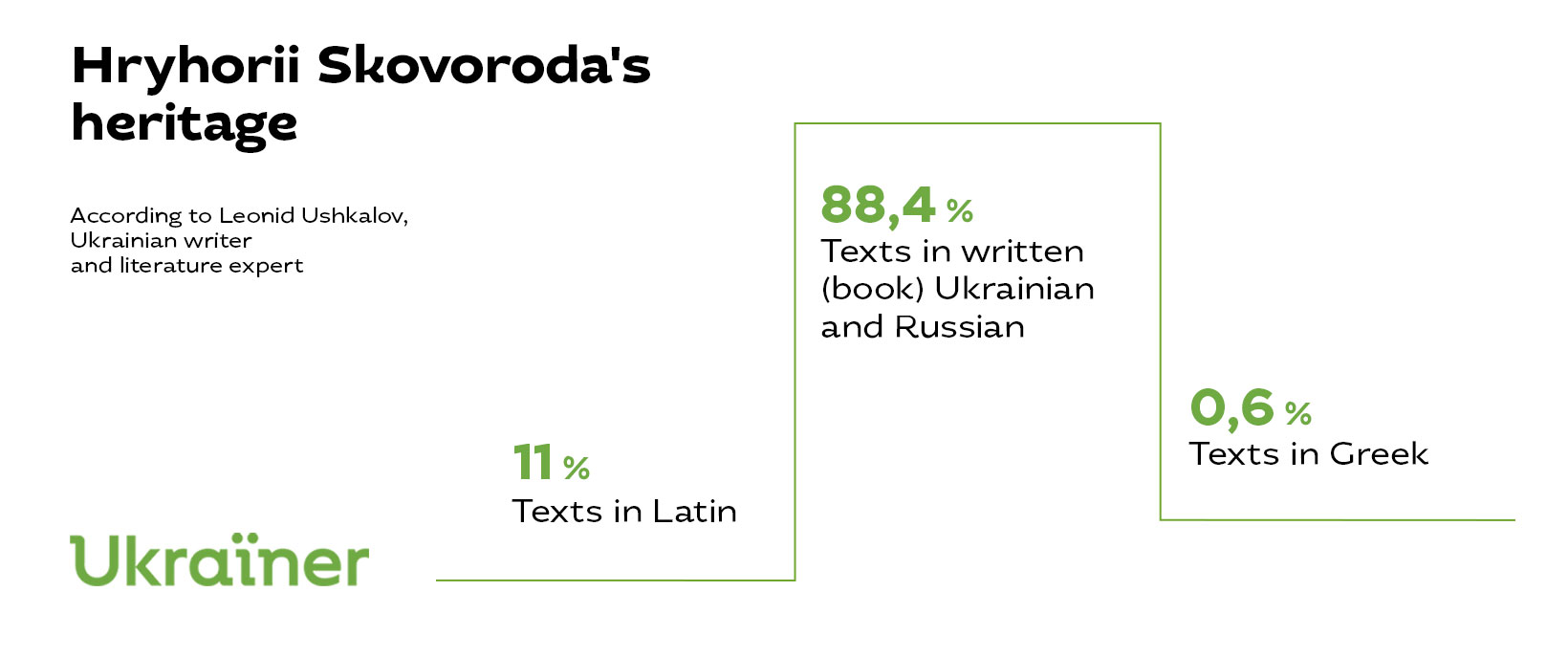

Around this time, 1766-1772, Hryhorii Skovoroda was working on philosophical treatises and began writing “Kharkiv fables”. In everyday life, he speaks Ukrainian, according to his memoirs: “with an accent of a true little Russian”. But Skovoroda’s creative legacy, according to Leonid Ushkalov’s observations, is divided into three main parts from the point of view of language.

What dictionary did the author use? Modern people feel familiar with, for example, the neologisms of Skovoroda, some of which deserve to break into the present day and become a brand name or better characterize the current habits.

Heart to heart

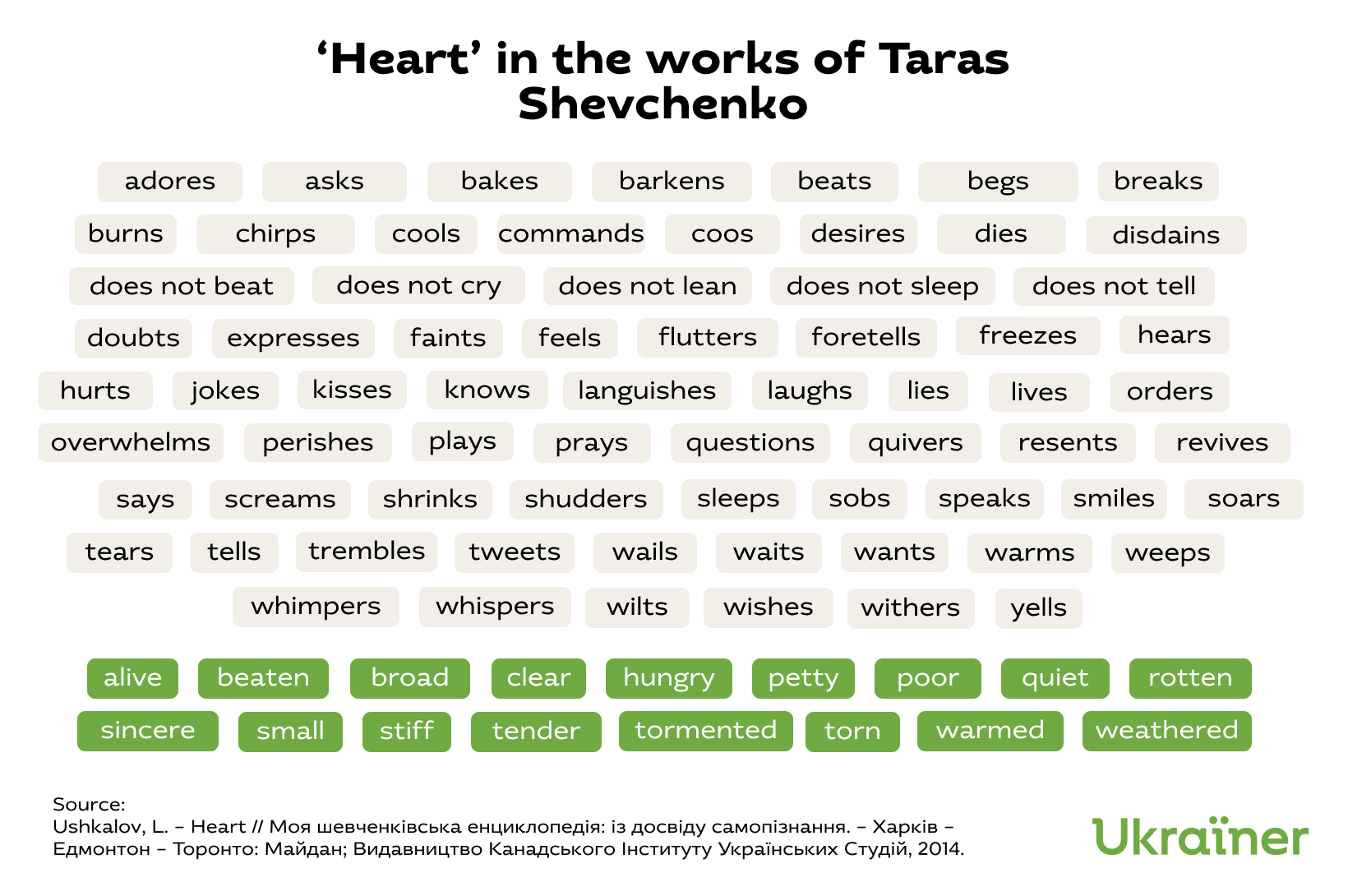

Skovoroda is responsible for the formation of a special Ukrainian philosophy — cordocentrism, the philosophy of the heart. According to D. Chyzhevskyi, H. Skovoroda considered the emotional and voluntary nature of the human spirit, which is the “heart” of man, to be the central one. From the heart “grow thoughts, aspirations, and feelings”.

In the 1940s, the Ukrainian writer and centurion of the UPR Army, Yevhen Malaniuk, said of Ukrainians: “We are cordocentric people.” He immediately revealed the central conflict that occurs here: “And this is the doom of my people, which is both its weakness and its strength.” When looking at Skovoroda’s works, Leonid Ushkalov estimated that the image of the heart is mentioned 1,146 times in different contexts. Ushkalov notes that this is “almost two and a half times more common than the name of Christ”.

It seems that the heart behaves like a shadow in the fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen, which separates from its owner and becomes independent. Well, or like the “nose” of Major Kovaliov in the story of Mykola Hohol — it becomes its own goal.

And Shevchenko’s heart can also be like this: painful, rotten, hungry, alive, tortured, small, heated, cold, beaten, torn, quiet, complicated, poor, washed, broad, and sincere.

Shevchenko also has an example of a conversation with his own heart. He talked to it like it was a living, independent entity.

“Why do I feel so heavy? Why so weary?

Why does my soul in wailing grief lament

like a starved child? Ah, heart oppressed and dreary,

What do you wish? What is your discontent?

Are you for food, or drink, or sleep aspirant?

Sleep, then, my soul! Forever sleep apart,

Shattered, uncovered…

Let the senseless tyrant Rage ever on…

Close, close your eyes, my heart.”

(Translated by С.H. Andrusyshen and Watson Kirkconnell)

It is clear that the “heart” beats not only in Ukrainian cordocentrism. And the Western tradition has its own huge history from Plato and the Bible to Thomas Kemp.

But even more interesting is how the heart-oriented and heart-driven nature of folk songs has become an integral part of pop culture.

And it is important to remember this “cordiality” of Ukrainian philosophy in your mind. For every “My Heart Will Go On,” there is “My Heart” by Sviatoslav Vakarchuk, and in the chorus, we will sing together:

В небі зійшла зоря,

Бачить із висоти,

Як моє серце

Рветься і плаче,

Та не помічаєш ти…

The uncontrolled element of burlesque

We can also find examples of humor and satire in more ancient examples of Ukrainian literature, but they are rather non-systemic in their nature. But at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries, the element of satire broke into Ukrainian literature. In general, a something new is forming among educated people who wander in search of overcoming difficulties. This group includes wandering students, deacons, and monks.

Holiness begins to allow laughter. A new slogan is proclaimed: the simple are able to express high truths. And in the Baroque era, even Christ smiled. Skovoroda asks rhetorically, “When did Christ laugh? This question is very similar to this sophisticated one: does it happen when the sun is hot? What are you saying? Isaac, Abraham’s son, that is, laughter, joy, and cheer…”

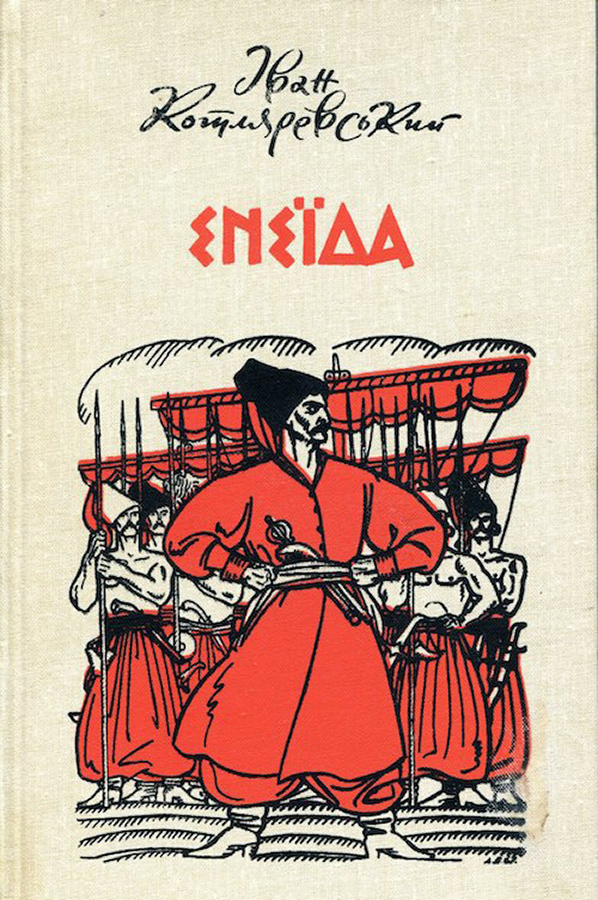

1968 edition of The Aeneid with illustrations by Anatolii Bazylevych.

In 1794, Hryhorii Skovoroda died. And Ivan Kotliarevskyi undertakes to twist Virgil’s “Aeneid” in his own way, creating a remake. He took the original source’s characters and plot, changed the mood, and painted it in the colors of Ukrainian culture.

The Aeneid had an amazing and lasting effect. This applies, for example, to the choice of a language that signals separation from the entire imperial context. According to Hryhorii Hrabovych, the main function of the works written by Kotliarevskyi’s followers was to ridicule the pompous, smug, artificial imperial society and normative, canonical literature (and hence the next level — the dependence of Kotliarevskyi’s style on colonial status).

The element of Ukrainian laughter hit the Russian Empire. Mykola Hohol, a writer from the Poltava region, taught Russia to laugh. Hohol’s laughter was mentioned separately by the Russian philosopher Vasilii Rozanov, who felt M. Hohol’s destructiveness towards Russia and called it an even greater misfortune than the Mongol yoke. And, of course, his words: “Hohol unscrewed some kind of screw inside the Russian ship. After that, the ship began to fall apart. The unrestrained, slow sinking of Russia from year to year has begun”.

Hohol’s legacy is associated with one of the most important films in the history of Ukrainian cinema — The Lost Letter (1972, directed by Borys Ivchenko). Formally, this is an adaptation of the story, but the film still forms its own burlesque rules of the game and outlines the lines of Ukrainian identity. Somewhere at this time (the 1960s and 70s), a special type of literature was formed called “Ukrainian fantasy”, where irony occupies a prominent place among other expressive means.

The burlesque element of Ukrainian literature reached a new stage in the second half of the 1980s, when Yurii Andrukhovych, Viktor Neborak, and Oleksandr Irvanets founded the literary club called Bu-Ba-Bu (Burlesque, Farce, Buffoonery), which destroyed the dam of officialdom. What directly called for their texts to connect with the Ukrainian “baroque”? Some researchers consider the publication in 1992 of Yurii Andrukhovych’s debut novel Recreations as the beginning of modern literature, as it was already with The Aeneid.

Canon: “Not everyone has returned yet, but not everyone has left yet.”

Stonemason, or not a Stonemason.

Mykhailo Semenko, the poet, founder, and leader of Ukrainian futurism in the 1920s, described the harm caused by the religious worship of Taras Shevchenko as follows: “if there is a cult, there is no art… Your honor has killed it”. He also urged: “Let our parents (who did not give us anything as an inheritance) enjoy their “native” art. And living together with it, we young people will not shake hands with them. Let’s catch up with today”.

Every literary generation attempts to overthrow its predecessors in literature or infringes on the icons of national literature. But, despite everything, the basis of the Ukrainian canon, which includes Kobzar, Prometheus’ daughter, and “Kameniar” (Taras Shevchenko, Lesya Ukraiinka, and Ivan Franko) — remains indifferent to the attempts of new generations to desacralize, debunk, and throw off their pedestals.

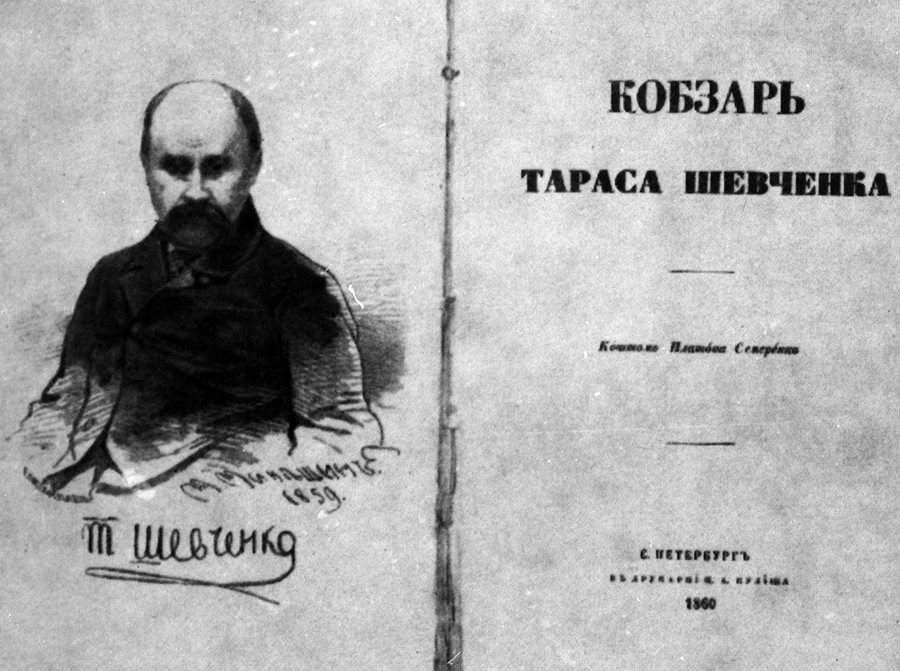

The concept-brand “Kobzar” appears during Shevchenko’s lifetime comes from the name of his first poetry collection (1840, eight poems, 114 pages). Later, after the exile, the semantics of “Kobzar” will be added — a fighter for truth and justice, a martyr.

The title page of Kobzar by Taras Shevchenko (1860). A reproduction. Source: Central State Cinema, Photo and Audio Archives of Ukraine n.a. Pshenichny

Kobzar is a singer, primarily blind, who becomes the embodiment of collective memory. Literary critic Hryhorii Grabovych calls Kobzar a “shamanic intermediary” between collective memory and higher forces — “history, heaven, God”. Shevchenko’s concept of the people, with the people and only for the people, comes to the fore ideologically. And, like any canonization, this leads to the cutting off of everything that initially contradicts the given concept and underestimates the texts themselves (and the brilliant legacy of Shevchenko as an artist).

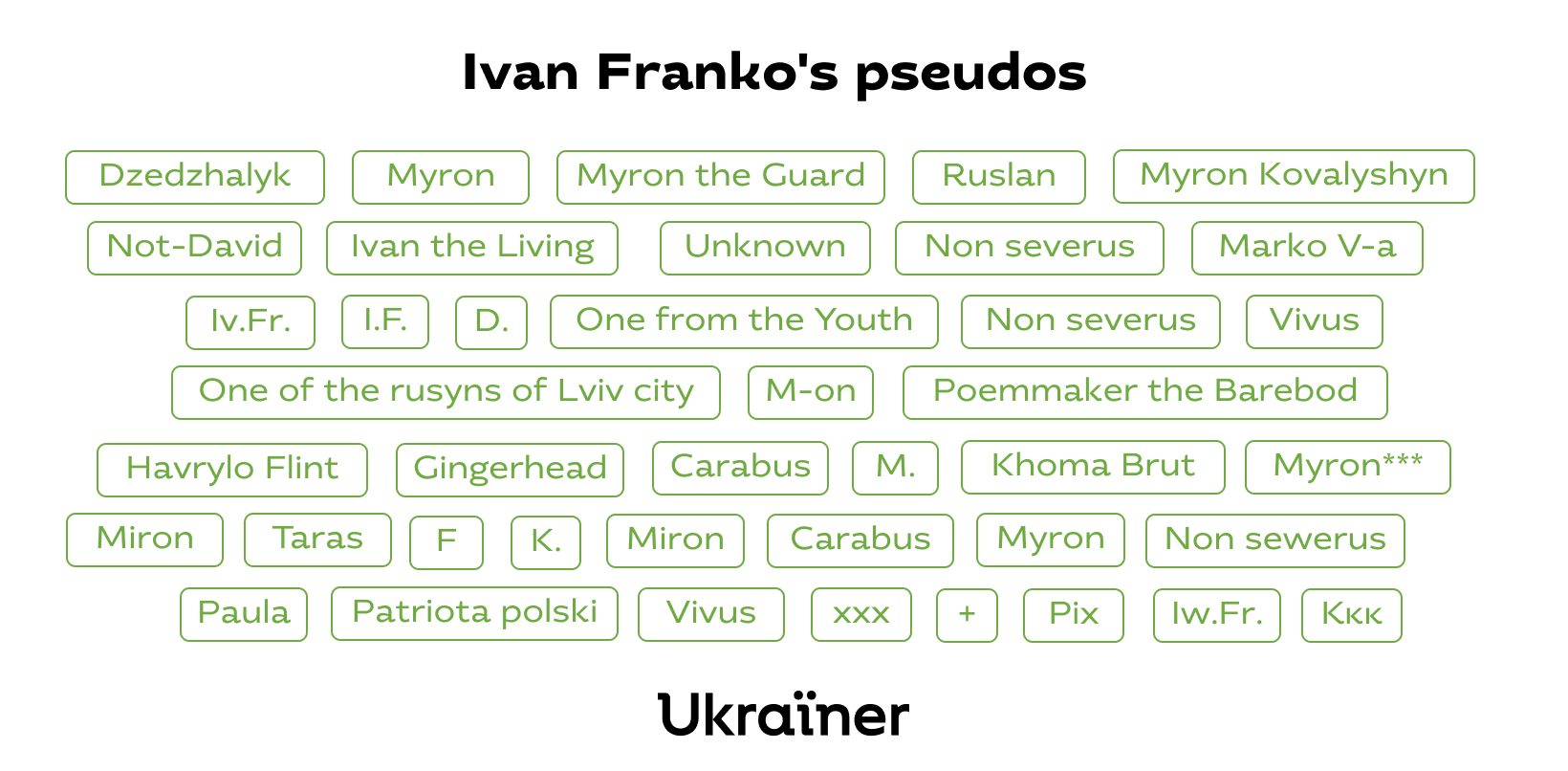

According to Hrabovych, in the concept of Kameniar, Ivan Franko is assigned one function, which is purposeful socio-social engagement, with a particular emphasis on the fact that he was a socialist, a realist, an atheist, and a materialist. But at the same time, several important accents are lost. And Tamara Hundorova’s book called Franko is not a Stonemason becomes a starting point for polemics about rethinking the usual formula.

Franko, the poet, is the author of 10 books of poetry, which include more than half a thousand individual works. Franko, the novelist, is the author of more than 100 short stories, including fairy tales and children’s stories, which have been compiled in 18 collections of short prose. Franko, the translator, translated into Ukrainian the works of almost 200 authors from 14 languages and 37 national literatures (some of them, however, through German). Franko, the scientist, has written over 3000 works, including studies on folklore, theory, and the history of Ukrainian and World Theater. And, of course, Franko is the author of the work called “From the Secrets of Poetic Creativity” (1898), in which he writes about the “lower consciousness” and its role in everyday life and artistic creativity. Franko had about 100 pseudonyms: Myron, Myron Storozh, Myron Kovalyshyn, Ruslan, The Unknown, Not David, Not Theophrastus, Non Severus, Vivus, Marko V-A, one of the youths, one of the Rusyns of Lviv, and others.

Canon and iconostasis

After gaining independence, numerous texts by repressed writers returned to literature. At the same time, the canon also includes works by Soviet writers who, sometimes, did not stand up to criticism, even at the time of publication. And, in the end, texts of different artistic significance and skill become the facts of the same stream.

The Australian literary critic Marko Pavlyshyn sees a special difference between the Western canon and the canon prevailing in Eastern Europe. The Western canon concentrates on texts, but in Eastern Europe, the object of veneration becomes “a set of biography of the writer, his works, and historical roll”. This can be said about Pushkin, Tolstoy and Dostoievskyi in Russia and Shevchenko, Lesya Ukraiinka, and Franko in our country. Pavlyshyn compares literary canonization in the Soviet Union with the canonization of a church saint. And thus, an iconostasis is formed from the following canonized authors: “The iconostasis directs the attention of the faithful to the person, their virtues, their significance, and their connection with the central idea of salvation. It is the person that attaches importance to their attributes, including the texts that are associated with them.”

The author’s introduction into the canon, “canonization,” and worship of the created myth about the author leads to a loss of focus on the texts themselves as well. At the same time, there is a cutting off of those facts of the biography that do not fit into the given ideological framework.

It is important to note that, in addition to the usual “triune” Ukrainian iconostasis (and Hohol), one way or another there are figures that are not trivial for understanding how diverse Ukrainian literature is. And their stable place in the iconostasis from time to time gets brighter coverage and a round of new reader interest.

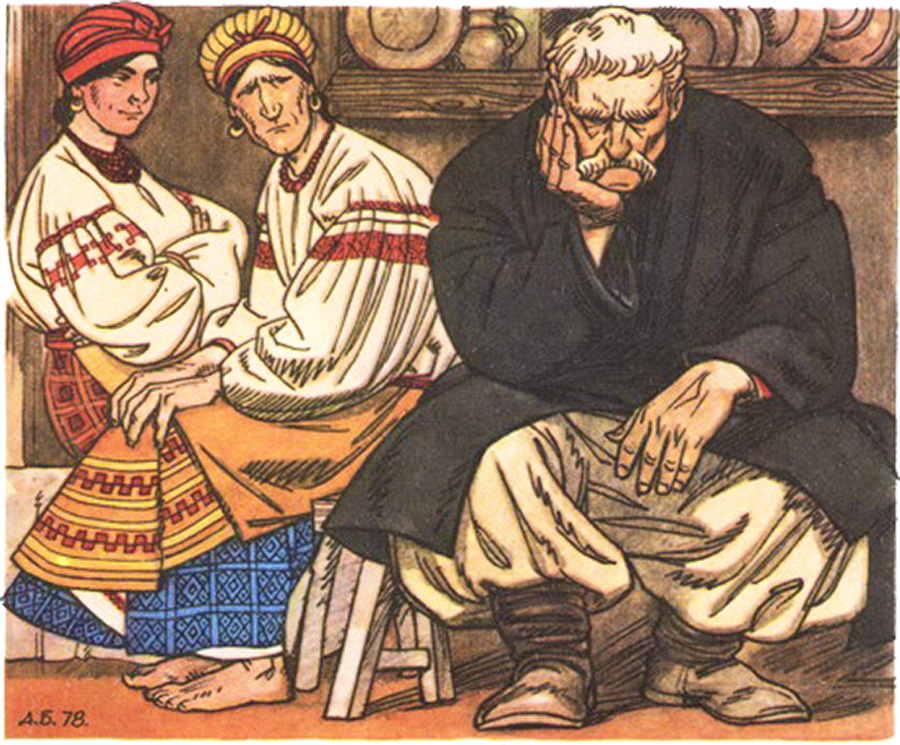

Illustration by Anatolii Bazylevych to Kaidash's family by Ivan Nechui-Levytskyi.

For example, Ivan Nechui-Levytskyi’s Kaidash’s family (1878), which already serves as a kind of archetype of Ukrainian family history, is actualized in the form of a brilliant film adaptation of Catch Kaidash (2020), which was created by one of the leading contemporary playwrights Natalia Vorozhbyt. The family chronicle of the Kaidash feud turns into a reflection of the formation of Ukraine in the 2000s — 2010s.

One more example is the figure of Olha Kobylianska, who in a new round of research and discussions about the origins of Ukrainian feminism, has earned a newly interested audience. You can come across a quote from her memorable speech in October 1894 at a meeting of the Society of Russian Women in Bukovyna in Chernivtsi more and more often. Where, among other things, 31-year-old Kobylianska says: “The idea of emancipation of women, or the idea of a women’s movement, is actually the idea that proves the current situation of middle-class women, and especially unmarried women, is sad, worthy of the attention of all thinking minds, humane hearts of both genders, and sincerely wishes to improve women’s fate.”

Another example is the figure of Mykhailo Kotsiubynskyi, which appears not only as a brilliant cinematic interpretation of Serhii Paradzhanov and Yurii Illienko’s story Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, but also as psychological and impressionistic prose, which stands apart from the legacy of his contemporaries. By the way, the short story by Vasyl Stefanyk, which received a new range of discussions thanks to the next anniversary, was also published.

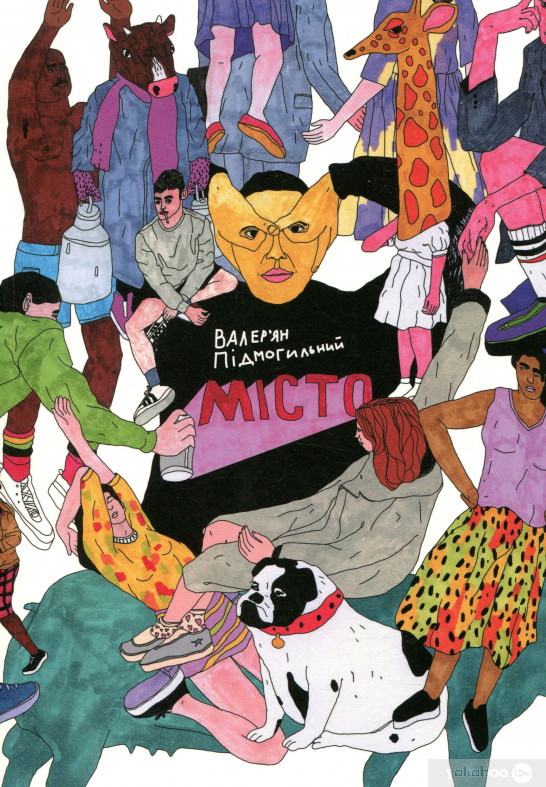

Cover of the The City novel by Valerian Pidmohylny. Osnovy Publishing House, 2017.

Also, non-trivial conversations about the intellectual novels of Viktor Domontovych and Valerian Pidmohylnyi can become a good antithesis to conversations about the cordocentrism of Ukrainian literature. And, of course, The City by V. Podmohylnyi also serves as an excellent antithesis to the usual topos of the village in Ukrainian literature.

Thus, not having a very successful novel debut may lead to rereading more ancient poetic works, as in the case of Lina Kostenko, without whom a broader idea of the iconostasis of the late twentieth century is impossible.

And the whole era of the Ukrainian 1920s is worth mentioning separately, which in parallel with our entry into the 2020s is gaining a new sound. We are not even talking about theses that are used in political campaigning and attributed to outstanding authors of that time (as in the case of simplifying the whole concept of Mykola Khvyliovyi to the thesis Get away from Moscow). We are talking about the return to the Ukrainian context of names and entire genres that deny the conditional incompleteness of Ukrainian literature. In parallel with this, the term “Ukrainian avant-garde” is constantly being established at the international level, which, finally, should distinguish this phenomenon from the shadow of the general “Russian avant-garde” in the broader world art history discussion. In recent years, Yaryna Tsymbal has organized anthologies that demonstrate the diversity of our 20s: collections of detective stories, romance novels, love prose, science fiction, women’s prose, as well as reportage, which contains observations of Ukrainian authors obtained during their travels to distant worlds (Iran, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Italy).

Summing up the thoughts about the Ukrainian “iconostasis”, Marko Pavlyshyn quotes a line from the poem by Nataliia Bilotserkivets — “Not everyone has returned yet, but not everyone has left yet,” which aptly characterizes the canon of the Independence times: not all names have returned yet, but some of those that remain have probably already lost their relevance.

It is illegal to prohibit

Ukrainian culture in general, and literature in particular, has almost always been a struggle, crystallized through resistance, overcoming prohibitions, repressions, and colonial influence.

Over the centuries, prohibitions have taken different forms and had different purposes. Obviously, among the historical examples, the most famous are two prohibitions. First, the Valuev Circular (1863) — a censorship ban on printing Ukrainian-language spiritual and popular educational literature. With particularly remarkable theses, the echoes of which we still hear: “There was no special little Russian language, there is not and can not be, and that their dialect, used by the common people, is nothing but Russian, only spoiled by the influence of Poland; that the Russian language is as understandable for little Russians as for great Russians, and even much more understandable than the dialect that some little Russians, and especially Poles, invent for them-the so-called Ukrainian language.”

The second, and no less well-known document is the Ems ukaz (decree) (1876) — a ban on printing and importing any Ukrainian-language literature and translations from foreign languages, as well as a ban on theatrical performances and music publications in the Ukrainian language.

In an attempt to replace the Ukrainian Cyrillic alphabet with Latin, closer to the time of the Valuev Circular in Eastern Halychyna and Bukovyna, which were under the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1859, the Ukrainian Cyrillic alphabet was replaced with Latin.

At different times, different authorities were afraid of celebrating the anniversaries of Ukrainian writers. For example, in 1914, it was forbidden to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Taras Shevchenko’s birth.

The Soviet system tirelessly and purposefully subjected Ukrainian artists to repression. The bloody, cold-blooded, and consistent extermination of a generation of incredible Ukrainian artists was especially egregious. They created Ukrainian literature in the era of modernism and the avant-garde in the 1920s. They made a real revolution in expanding genre diversity, poetic vocabulary, and stunning experiments with form and style.

Generations of dissidents and human rights activists were subjected to relentless persecution almost daily.

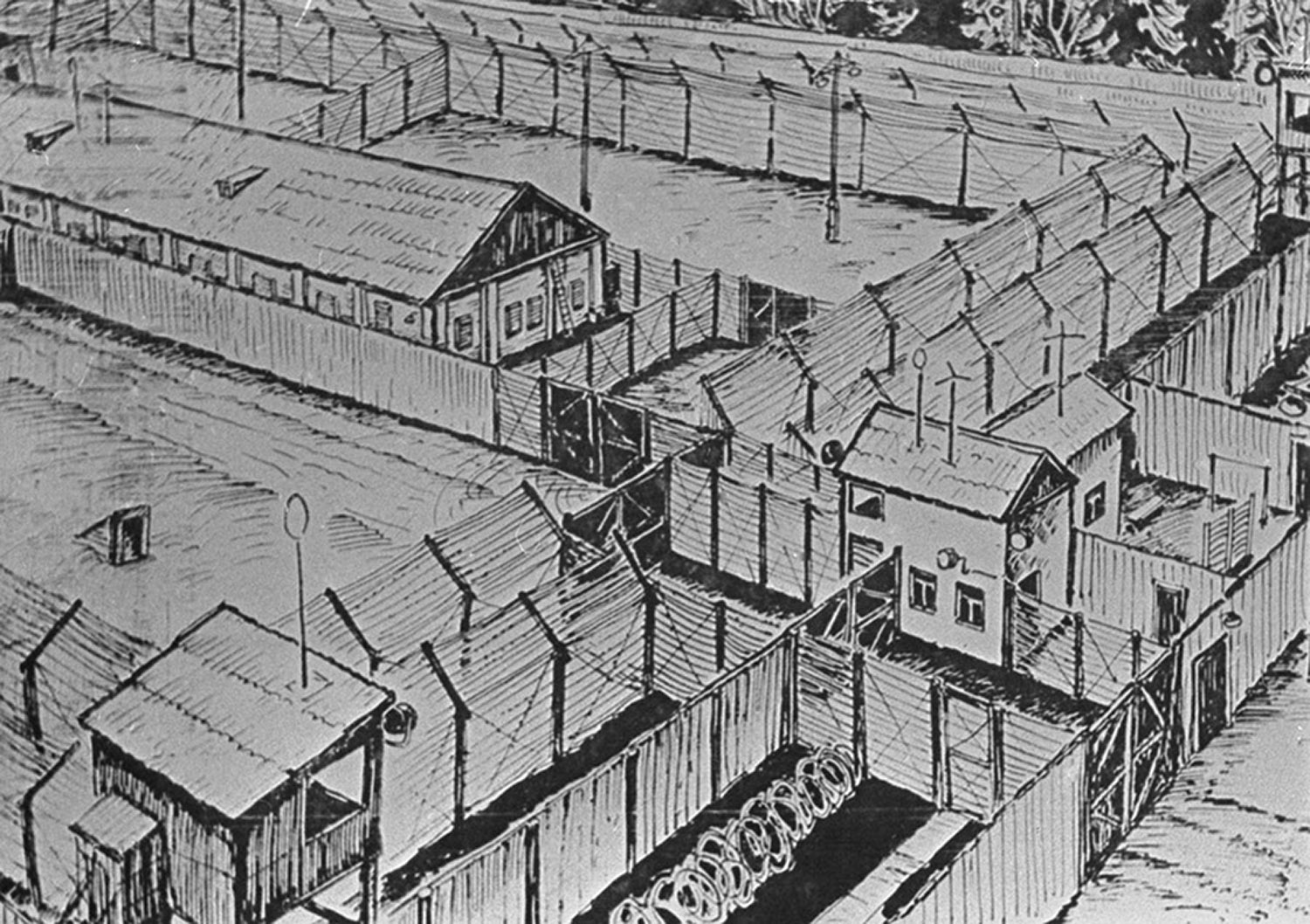

A corrective labor colony Perm-36 where Vasyl Stus was imprisoned. Drawing by L. I. Borodin, a writer. Source: Central State Cinema, Photo and Audio Archives of Ukraine n.a. Pshenichny

Needless to say, one of the most powerful Ukrainian poets, Vasyl Stus, was tortured in camps in 1985. At the same time, his last lifetime publication of poetry in the Soviet Union was in the magazine Donbass in early 1966. The next one happened four years after his death, in 1989.

1985 is the most recent time of repression for us.

It was the year when Mykhailo Horbachov announced a course for the reconstruction of the Soviet Union, Microsoft began developing the Word program, and Mike Tyson started a professional career as a boxer.

That year is not that long ago. Those who were friends with the poet are still alive. And those who tortured him are still alive.

External ban. Internal ban

The Soviet system created an environment hostile to languages other than Russian. This tendency consisted not only of prohibitions (the order on the defense of dissertations was only in Russian in 1970) but also in the system of bonuses and incentives (1984 was the beginning in the Ukrainian SSR of payments of increased salaries to Russian language teachers by 15% compared to teachers of the Ukrainian language).

However, not all bans were imposed from the outside.

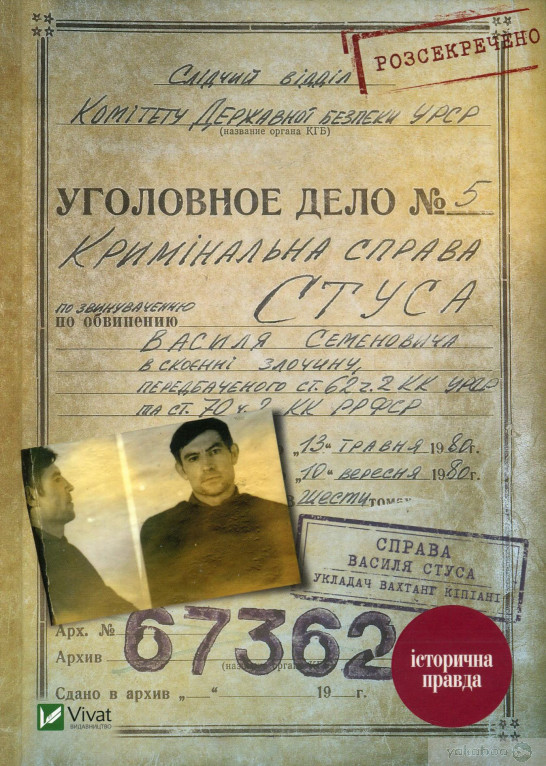

Cover of the book called The case of Vasyl Stus arranged by Vakhtang Kipiani. Vivat Publishing House, 2019.

For example, from 2004 to 2015, completely continuing Soviet traditions, the national expert commission of Ukraine on the protection of public morals operated. Several high-profile scandals are associated with its activities. The most famous is the 2009 ban on Olesya Ulianenko’s book, The Woman of His Dreams. The 10-thousandth edition of the book was withdrawn from sale after being accused of pornography, but was later returned to bookstores.

Among the latest examples of attempts to ban Ukrainian books was the attempt in 2019 by the pro-Russian politician Viktor Medvedchuk to ban the book called The Case of Vasyl Stus by Vakhtang Kipiani. In Soviet times, Medvedchuk was a state lawyer for Vasyl Stus.

Medvedchuk demanded to ban the sale of the book, as well as to recognize the following phrase as false in court: “… Medvedchuk admitted at the trial that all the “crimes” allegedly committed by his client “deserve punishment”. Among others, the following statement should be removed from the book: “he [Viktor Medvedchuk] actually supported the charges. Why do we need prosecutors when there are such reliable lawyers?”

In March 2021, the Kyiv Court of Appeal overturned the decision of the Court of First Instance to ban the publication of the book, and the total circulation of the publication, thanks to the broad support of society, reached 100 thousand copies.

“Build a homeland in our souls”: literature of exile

AUM: fill the void.

Ukrainian emigration took place several times. The first of which occurred at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. From the first time, which is considered labor, a small number of texts remained.

The second time of emigration is associated with the defeat of the national liberation struggle. First, in the 1920s, the “Prague School” was formed (although formally, not all association representatives lived in this city). The most important feature of Ukrainian literature of emigration is highlighted, which is an alternative to Soviet official literature. It was especially evident in the 1930s, first with the doctrine of unified social realism and then with repression.

The next powerful stage of Ukrainian expat writers was generated by the Second World War. AUM (Art Ukrainian Movement or Ukrainian Art Movement) is one of the few Ukrainian public institutions in the camps of the American occupation zone, where there were about 200 thousand Ukrainians. Among the founders: Viktor Petrov, Ihor Kostetskyi, Yurii Sheveliov, Ivan Bahriany, and others. Initially, it was decided that this association “should not be a type of Soviet Writers’ Union. It should be elitist, with the initiative group selecting members based on their literary merits.”

AUM writers (1947): in the bottom row — Yevhen Malaniuk, Yurii Sheveliov, in the top row — Vasyl Barka, Ulas Samchuk, Ihor Kostetskyi. Source: Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (IEU).

The defining idea of the movement was Ulas Samchuk’s thesis about great literature. Literature is the result of the history of the people, a manifestation of their soul and thinking, and at the same time it appeals to the human spirit as a whole. Experiment with form, let art for art’s sake fade into the background. According to U. Samchuk, “Every great work of literature is saturated with the authentic truth of life, which in its sum proves with mathematical accuracy that two times two is four, that we all, whoever we are and wherever we are, belong to the same community of living beings on Earth.”

AUM existed for three years, and more than 1,200 books and pamphlets were published in the camps, of which about 250 were publications of original works in poetry, prose, and drama. During the time of AUM, Ivan Bahrianyi’s Tiger Catchers, Viktor Domontovych’s Doctor Seraficus and Without Foundation, Ulas Samchuk’s Ost and others were written or first published.

Subsequently, Yurii Sherekh remembered: “We lived in Germany, but we had no ties with intellectual Germany… I imagined life in Ukraine according to the pre-war model, how destroyed Ukraine was rebuilt, through what difficulties and tensions, through what terror it passed through, we did not imagine.” We were surrounded by emptiness, and we filled it with illusions.

Within a few years, some of the writers died or left the group. In 1949, many writers who were in camps for displaced persons left Germany, mainly for North America.

But in Germany, for example, the poet and translator Ihor Kostetskyi remained, who, together with his wife Elizabeth Kotmayer, founded the On The Mountain Ukrainian Publishing House, whose active publishing activity lasted until the 1970s. The first book of the publishing house was a collection of poems by Thomas Stearns Eliot, translated by Ihor Kostetskyi. Also published here were Ukrainian translations of Shakespeare, Verlaine, Baudelaire, Dante, Ezra Pound, and others.

New York: Modernism again

In the 1950s, many Ukrainian cultural figures lived in New York and its suburbs. Therefore, it is no coincidence that a new literary formation called the “New York Group of Poets” was set up here. The group included “people who were born in Ukraine at the turn of the 20s and 30s, spent their childhood or teenage years with their parents in displaced persons camps, and received their education after the war in America or in other Western countries.” Both cultures, Ukrainian and American, were native to the group members.

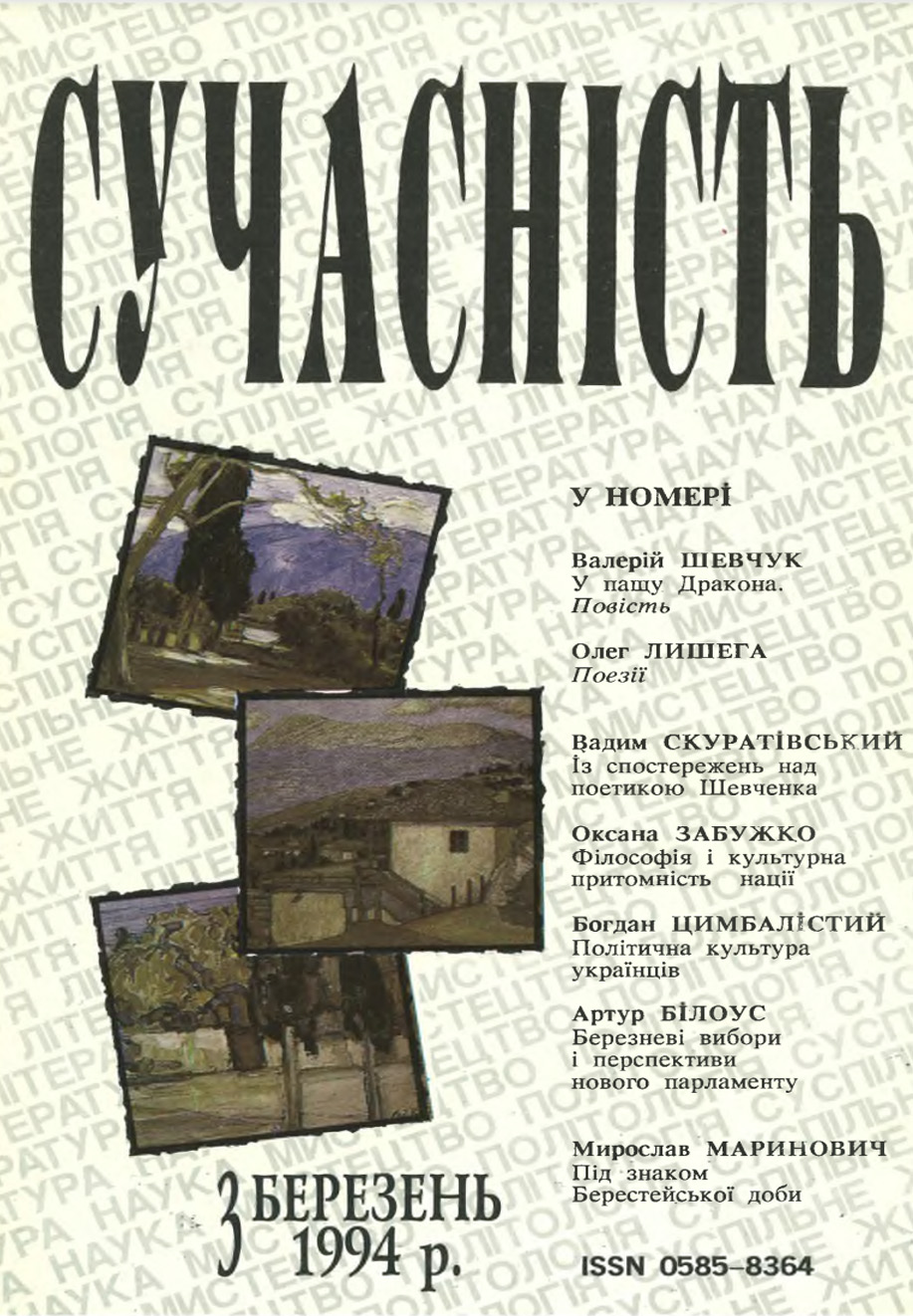

Cover of Modernity magazine, 1994.

In the mid-50s, the first books by members of the future New York group were published. They were written by Bohdan Rubchak, Bogdan Boichuk, Yurii Tarnavskyi, Vera Vovk, and Emma Andiievska. The group was formed approximately in 1958.

According to the observation of Solomiia Pavlychko, the writer and literary critic, the New York group of poets “associated themselves with New York, and accordingly, with the dynamics, cosmopolitanism, and permanent modernity of this city, as well as its sensitivity to the artistic avant-garde.” According to S. Pavlychko, a radical difference from the provincialism that is rooted in the native literary tradition becomes unifying. But at the same time, the connection between Ukrainian literature and modernism was renewed after losing a whole generation of artists in the 1930s.

In 1961, Modernity magazine was founded in Munich, and for 30 years it was published in Germany and then in the United States. The magazine had become an essential platform for Ukrainian diaspora intellectuals. In 1992, the magazine’s editorial office moved to KyiIn the mid-50s, the first books by members of the future New York group were published. They were written by Bohdan Rubchak, Bogdan Boichuk, Yurii Tarnavskyi, Vera Vovk, and Emma Andiievska. The group was formed approximately in 1958.v, foreshadowing the unification of literary processes (it is noteworthy that, having survived adversity for 30 years of foreign existence, the magazine was finally closed in 2013 in Kyiv after considerable turbulence).

In all these decades, the Ukrainian Free University in Munich, the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, and the Ukrainian Research Institute of Harvard University have remained essential tools for international representation of the Ukrainian voice.

In his memoirs about AUM’s activities, Yurii Sherekh probably formulated the very essence of the literary and artistic process in exile: “We ended up in a foreign land; we lost without playing political bets. If there could not be a homeland on the geographical map, we could build a homeland in our souls.”

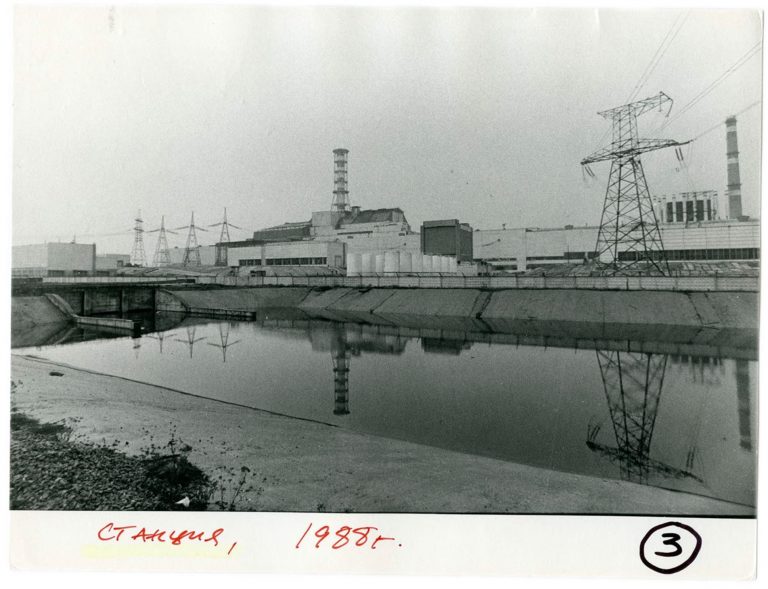

Literature after the Chornobyl tragedy

On April 26, 1986, an accident occurred at the fourth power unit of the Chornobyl nuclear power plant, which caused an artificial environmental and humanitarian catastrophe. Ukraine’s total economic losses are estimated to be 179 billion dollars. As a result of the disaster, 1.96 million people were affected, including 191,260 participants in eliminating the consequences of the accident.

According to Tamara Hundorova, the Chornobyl disaster is considered the beginning of the countdown of Ukrainian postmodernism, with its attributes of the end of the world and the finality of history, which brings irony to the forefront as a powerful attempt at an antidote. Hundorova says: “In general, Ukrainian postmodernism is a post-Chernobyl text… The Chornobyl disaster coincided with the disintegration of totalitarian Soviet consciousness, and it became a symbolic backdrop against which both consciousness and literature changed.”

slideshow

Tamara Hundorova traces the dynamics of perception of the Chornobyl accident as a kind of symbol. In the 90s, Chernobyl was part of Ukraine’s struggle for independence, and the idea of “spiritual Chornobyl” came to the forefront. In the early 2000s, Chornobyl was embedded in a broader sense of catastrophism — “in the sense of destroying the environment, health, threats to nuclear energy, and culture.” Now, Chornobyl is increasingly associated with the first signals of the collapse of the Soviet Union.

A technological catastrophe of this magnitude and ideological destruction on another level leads to the search for a new language and dictionary, new means of expression for understanding the bizarre reality.

Here we will note that the Chornobyl catastrophe can not be taken as the exclusive starting point of modern Ukrainian literature. After all, many modern writers made their debut in the first half of the 80s, or even earlier (for example, the first book by the above-mentioned Nataliia Bilotserkivets was published in 1976). The foundation of the Thursday magazine in 1989, which gathered a community of extremely talented authors, contributing to the formation of the so-called Stanislavsky phenomenon, can also be considered so. There was the publication of the novel Field Research on Ukrainian sex by Oksana Zabuzhko in 1996. There was the meeting of three poets, namely, Yurii Andrukhovych, Viktor Neborak, and Oleksandr Irvanets, and the group that they formed.

Irony as a weapon

The Bu-Ba-Bu literary group, founded a year before the Chornobyl disaster, significantly contributed to the rethinking of the new reality. In particular, Oleksandr Irvanets, one of the participants of Bu-Ba-Bu, takes irony as one of the essential tools for twisting the socialist realist canon. As Andrii Bondar says: “The poet seems to be counting on many psychological complexes of Ukrainian poetry of the Soviet era at once — with tearful lyricism and social romance, with servilism and official patriotism, with creative passivity, and again romance.”

For example, in the large-scale text of 1992 called “An open letter to the Prime Minister of Canada, Brian Mulroney, and Governor-General Roman Gnatishin from the workers of the collective farm “Illich’s way” (crossed out) “Ilkovych’s way,” which, recounts the endless proclamations of the Soviet ordinary people to the whole world and also records numerous signs of modern times:

We can’t drink or eat here,

Nor read newspapers and books,

While the Quebec separatists

Tear your body to pieces,

Long-suffering mother-Canada!

We’re surprised by your silence.

What do they want? What else do they want?

What else are they missing from you?

Even in a stricter form of travesty, irony will break out in the plays of Les Podervianskyi. He gave several generations of listeners capacious formulas for diagnosing reality for any life occasion.

In recent years, the story of Chornobyl has had a brilliant artistic reinterpretation, such as in Pavlo Arie’s play called At the Beginning and End of Time (the theatrical hit Stalkers staged by Stas Zhyrkov) and books by Markian Kamysh. His debut, Stalking the Atomic City Life Among the Decadent and the Depraved of Chornobyl, was translated into Italian and French, and English, and is expected soon. Two important non-fiction books have also appeared. Serhii Plokhii’s research, Chornobyl. The Story of a Nuclear Disaster, was awarded the British Baillie Gifford Prize for Best Non-Fiction, as was the book by Kateryna Mikhalitsyna and Stanislav Dvornytskyi, Reactors Don’t Explode. A brief history of the Chornobyl disaster, addressed to a teenage audience.

With the completion of the confinement of the fourth power unit, it seems that jokes about Chernobyl are disappearing into oblivion. For example, those that have the same postcolonial subtext:

Ukrainians ask Moscow:

— How will we continue to live?

— Badly. But not for long.

Or like this:

The KGB warns:

— For spreading panic rumors, you’ll be imprisoned for three years. If the rumors are confirmed, the sentence is seven years.

Friday, Robinson, and more

To explain Russian-Ukrainian relations, Mykola Riabchuk uses the classic example in postcolonial studios with Robinson Crusoe and Friday: “each Robinson “loves” his Friday — but only as long as Friday accepts the rules of the game imposed on him and recognizes the colonial subordination and general superiority of Robinson and Robinson culture. As soon as Friday decides to rebel, which is to declare himself sovereign and equal to Robinson, and his culture as valuable and self-sufficient, he becomes a bourgeois-nationalist traitor who belongs in prison. The “normal” Friday is the one who dutifully accepts Robinson’s hugs; the “abnormal” is the one who finds them excessive, humiliating, and tries to break out of them.

Since independence, the question has been raised whether it is possible to apply the methodology developed by post-colonial studios to the experience of post-Soviet countries.

The classic signs of colonization are the lack of sovereign power, restrictions on travel, military occupation, the lack of a convertible currency, the subordination of the national economy to an external hegemon, and the forced study of the colonizers’ language. American researcher David Moore, considering these categories, and finally concludes that the Central European peoples were really under Russian-Soviet control.

Oleksandr Motyl uses the term “supremacism” to denote a dismissive attitude towards the Ukrainian language as the dominant trend in Soviet society. In such circumstances, using a particular language removes the symbolic meaning and the language becomes a political marker: “Ukrainian dissidents felt that the use of the Ukrainian language was tantamount to opposition to the Soviet state.” Using a language other than the official language may be interpreted as a refusal to accept “the people’s friendship” and demonstrates a dislike for “Soviet citizens”.

Marko Pavlyshyn suggests distinguishing between anti-colonialism and postcolonialism. Anti-colonialism is a sharp attempt to form a narrative alternative to the Imperial one, where the values that were oppressed under colonial rule come to the fore. Anti-colonialism was manifested in the fight against historiographical myths, including the deconstruction of the myth of the brotherhood of Slavic peoples and the coverage of numerous actions to destroy Ukraine.

According to M. Pavlyshyn, on another level, postcolonialism works because it creates a space free from the ideology of playing with old colonial myths, subordinating them to their own aesthetic tasks. The key techniques are irony, parody, and carnival. The uncontrolled element of Ukrainian burlesque at a new stage of history once again breaks the ideological dam.

slideshow

In 1954, Yurii Sherekh wrote an article titled “Moscow, Maroseika”. That year, the USSR celebrated the 300th anniversary of the so-called reunification of Ukraine with Russia. Sherekh’s article ends with the following words: “The history of cultural ties between Ukraine and Russia is the history of a great and not yet over war. Like any war, it has offensives and retreats, captives and prisoners. The history of this war must be studied.”

Back in 2013, speaking about the types of colonialism, Mykola Riabchuk expressed the fundamental idea that applying a post-colonial approach to the Ukrainian situation is acceptable. Still, “it would be naive to believe that the post-colonial course explains all Ukrainian problems.”

“Each of us will have new dreams”: here and now

“Somewhere out there, near the Svyatoshyn military enlistment office, my wife remained, confused and focused on new challenges. She had also begun a new life, full of cold nights and awkward mornings. How long will we not see each other? A month? Two? A year? Or never?

Then, for the first time, I felt like I was living someone else’s life. And from now on, I will see someone’s dreams. And I will take someone’s place to become a hero, to become a coward, or die.

One way or another, each of us will have new dreams.”

So ends the first essay from the book Absolute Zero by Artem Chekh, a writer who spent ten months in the ranks of the armed forces of Ukraine in 2015-2016. With the revolution of dignity, the annexation of Crimea, and the hybrid Russian-Ukrainian war, several radical social, cultural, and literary paradigms are taking place. And new dreams come.

Writers go to war. And those defenders of Ukraine, who probably would never have tried themselves in writing, transform their experience into literature. The most interesting literary phenomena of recent years are somehow connected with the understanding of the war and its consequences: Boarding School and Mariia’s Life by Serhii Zhadan; Amadoka by Sofia Andrukhovych; Long Times by Volodymyr Rafieienko; The Death of Cecil the Lion Made Sense by Olena Stiazhkina; Daughter by Tamara Horikha Zernia; Prison Song by Olena Herasimiuk; Bad roads by Nataliia Vorozhbyt.

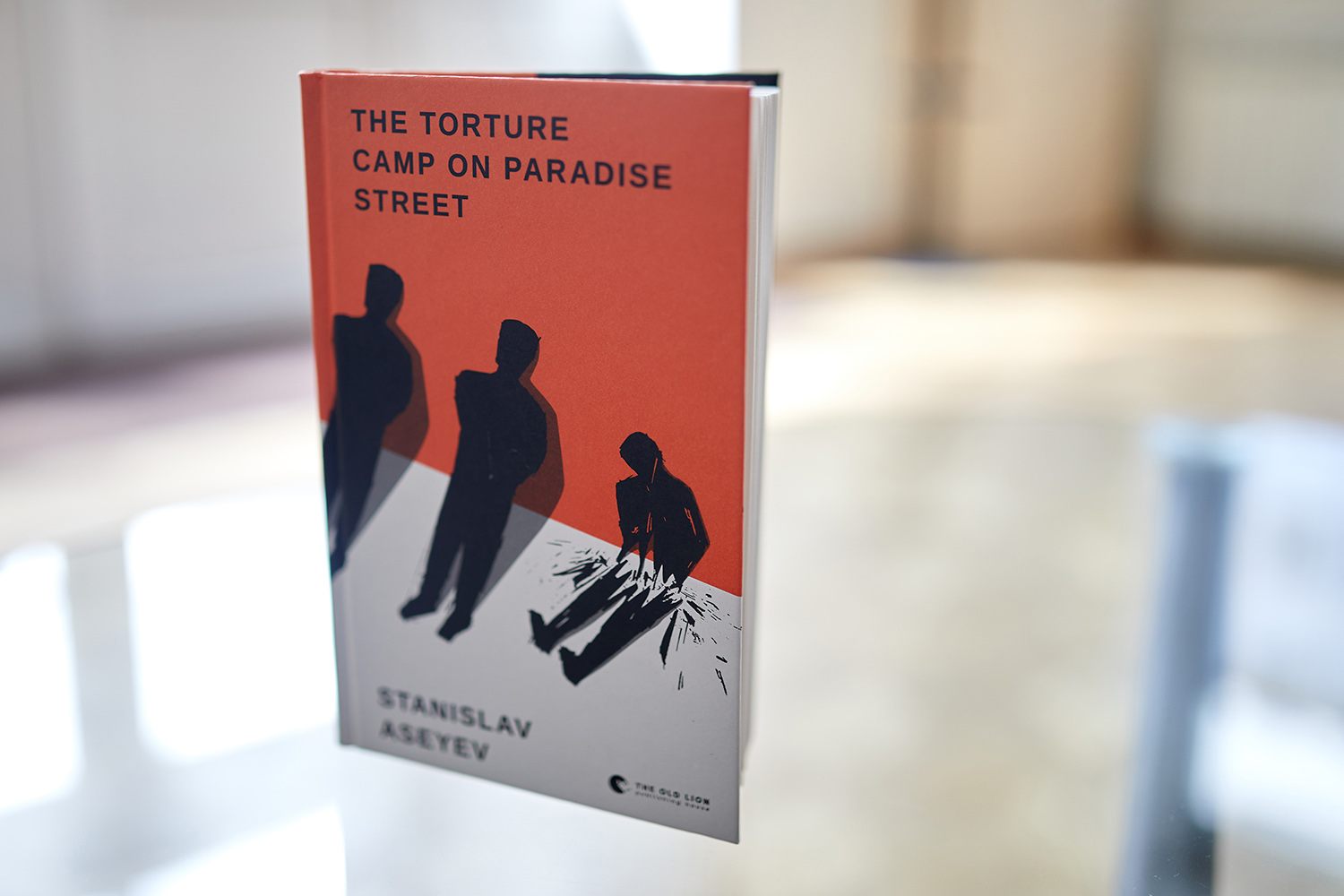

Cover of the English-language version of the book The Bright Way by Stanislav Asieiev.

Separately, some books are embedded in the tradition of camp prose in a new round of horror, for example, The Bright Path. The story of a Concentration Camp by Stanislav Asieiev and Chronicle of a Hunger Strike by Oleh Sentsov, each of which passed through the torture chamber. Stanislav Asieiev was abducted on May 11, 2017, and held by the pro-Russian terrorist organization “DNR” until December 29, 2019. Oleh Sentsov was detained in Simferopol by Russian security forces on May 10, 2014, and sentenced on August 25, 2015, on charges of terrorism to 20 years in prison to serve his sentence in a high-security penal colony. On September 7, 2019, he returned to Ukraine thanks to the exchange program of Russian criminals from Ukraine for Ukrainian prisoners of war from the Russian Federation. It is also worth recalling several in-depth conversations with the writer and philosopher Ihor Kozlovskyi. He rethinks his experience of being imprisoned by the so-called DNR militants, which lasted 700 days.

Recent years really seem to be the heyday of Ukrainian non-fiction and essayism, for example, books by Oleksandr Boichenko, Vakhtang Kebuladze, Diana Klochko, Tamara Martseniuk, Andrii Liubka, Taras Liutyi, Taras Prokhasko, Anna Uliura, Volodymyr Yermolenko, and others. The Yurii Shevelev Award for achievements in the field of essayism has been established since 2013. In the BBC Book of the Year contest, the corresponding nomination finally appeared in 2018. The importance of non-fiction here can have several explanations. On the one hand, the beneficial interest of the modern reader is in acquiring knowledge, developing, and acquiring new competencies. On the other hand, the flickering of post-truth and endless fake bubbles lead to the search for support for authoritative knowledge, literally for verified information. Finally, self-realization by Ukrainians, the awareness of their identity, leads to an interest in Ukrainian history, traditions, modernity, geographical charm, and art.

After the Maidan, new institutions are being formed aimed at strategic thinking and implementing long-term initiatives. The Ukrainian book Institute regulates State Library purchases and implements the Translate Ukraine translation program (57 translations of Ukrainian authors were published worldwide in 2020, 90 publications are expected in 2021). The Ukrainian Cultural Foundation provides stable support to the cultural sector. It supports various publishing initiatives (while among the requirements of the UCF is a healthy-thought-out plan of presentation events, leading to better promotion of publications funded by the foundation). The Ukrainian PEN is playing an increasingly active role with its particular focus on human rights activities, support for freedom of speech, and the presence of the voices of the country’s leading intellectuals in the public sphere. PEN also embodies important special projects, such as “From Skovoroda to the Present: 100 Iconic Works in Ukrainian”.

slideshow

The National Cultural, Art, and Museum Complex called “Mystetskyi Arsenal” serves as a platform for strategic support for the development of literature. We are talking about the largest book festival called Book Arsenal, and the activities of the Arsenal academic laboratory, and the project called “Literature for export”. In 2021, 21 Ukrainian publishing houses and 41 foreign ones from 22 countries negotiated between Ukrainian and international publishers. The Ukrainian Institute, the Ukrainian PEN, and the Ukrainian Book Institute are launching the Drahoman Prize to support and celebrate translators from Ukrainian to the languages of the world.

The Publishers’ Fair has a new name: Book Forum Lviv. Every September in Lviv (since 1994), it presents a non-comprehensive program of presentations, discussions, and literary and artistic events.

But here the following must be noted. Each of these state institutions is now under enormous external pressure and attempting to manage processes manually. The entire functioning of institutions is possible only if they are independent and not in anticipation of another raider seizure by the bureaucracy.

A ban on importing goods originating from the Russian Federation into the customs territory of Ukraine has begun. A considerable list includes onions, chocolates (sweets with alcohol). This also applies to veterinary vaccines, fertilizers, cans for canning, and motor vehicles. Finally, restrictions on the import of books from the aggressor country have partially come into effect.

Even with such a partial restriction on the import of Russian books, the general flourishing of Ukrainian culture and the interest of Ukrainians in Ukrainian led to a revival of publishing and the formation of new trends. For example, the documentary filmmakers put the succinct word “flash” in their series about post-Maidan Ukrainian culture.

For example, niche publishers that specialize in non-fiction are producing books for children and teenagers with a deep study of the historical context and advice from a psychologist (Portal), books about art and design (ArtHuss, IST Publishing), translated and Ukrainian reportage (Choven), selected translated modern classics (Babylonian Library), science fiction, and just about everything in the world. It does notmatter how strange this definition of niche specialization sounds (Vihola, Laboratory). Special mention should be made of the appearance of several publishers that specialize in translated and original comics and graphic novels, while at the same time attempting to form a terminological apparatus. Here the main thing is the approval of the specific term “maliopys” (Vovkulaka, UA Comix, Mal’opus — a publishing house whose activities are not limited to purely comics).

Along with the development of niche publishing houses, more vigorous testing of new forms of books begins including e-books, audiobooks, art books, book blogs, podcasts about literature, and podcasts that become books (for example, In Simple Words, which has become a reasonably successful book). However, the tendency to destroy cultural departments in the Ukrainian media and reduce the number of sites interested in detailed literary and critical materials is becoming increasingly threatening.

The decentralization of Ukrainian culture is also reaching a new level, and contemporary literary festivals are emerging all over the country. Not to mention the tours of Sergii Zhadan and Max Kidruk, in which the number of cities of performances can reach hundreds.

The issue of literature in the languages of people living on the territory of Ukraine deserves special attention. There are several processes going on here. For example, some works focus on the author’s conscious transition to the Ukrainian language. In the novel Mondegrin by Volodymyr Rafieienko, the discovery of the element of the Ukrainian language becomes almost the main plot, and in the book The Death of the Lion Cecil Made Sense by Olena Stiazhkina, sections in Russian and Ukrainian generally alternate. Meanwhile, the novels of one of the most exciting debutants of recent years, Illarion Pavliuk, are initially written in Russian, but they come to the reader exclusively in Ukrainian translations.

In 2018, at the initiative of the Crimean house, the first Ukrainian-Crimean Tatar contest, “Crimean figs”, was launched, which resulted in the publication of an anthology of texts of various genres, styles, and poetics united by a common theme of Crimea. Texts in Crimean Tatar and Ukrainian are published under one cover.

A vital conversation begins about the ethnic diversity of Ukrainian society. Olesia Yaremchuk has created a book of reports, Our Others, which contains stories about Armenians, Germans, Meskhetian Turks, Hungarians, Romanians, Roma, Swedes, and Crimean Tatars who create a fantastic polyphony of Ukrainian society. In 2021, Ukraїner published a book titled Who are we? National communities and indigenous peoples of Ukraine.

The fate of the dead, the fate of the living

For long periods, the book and song were almost the only means of preserving language and identity in Ukrainian literature.

Ukrainian writers rarely lived to old age. They rarely died of natural causes and received recognition during their lifetime.

Yurii Sherekh wrote: “The fate of dead writers does not differ significantly from the fate of living ones.”

History shows that new repressions, purges, denunciations, unfair trials, and fabricated cases are always there, or they’re already here.

Those who tortured artists in Soviet times are still alive and so are their methods.

I hope that one day there will be a generation of Ukrainian artists and writers who will not have to start all over again every time, who will be able to live a long and happy life, realizing all their plans.

They will also have readers who will discover their books. They will accept them as their own. We have a lot to be proud of. We have to remember.

In the meantime, you can also try to uncover the books of living and deceased writers.

You will love them.

P.S.

And finally, the last story. I don’t know if it’s worth looking for any symbolic meaning, but here we go. In the Chronicle of 1071, there is a version of the story about the creation of man: “And the devil created a man, and God put his soul into him. That is why when a man dies, the body goes to the ground, and the soul goes to God.”

supported by