Formerly an important industrial enterprise, today Zhytomyr’s “Elektrovymiriuvach” (“Electromeasurer”) plant mainly produces equipment for physics classrooms. In 2019 Andrii Chyburovskyi became its co-owner. He decided to preserve the plant’s capacities and create a socially meaningful project on its basis. An architect Roman Sakha and fundraiser Vita Bazan, he is converting former laboratories and warehouses into an innovative park, called Vymiriuvach (“Measurer”), based in the former laboratories and warehouses.

Here, visitors will be able to create a prototype of their own product, take part in a several days long residence to compose electronic music, work on a machine tool with various materials, find a new life for outdated parts and devices and create craft accessories. The “Vymiriuvach” team’s ambitious plans include helping to launch high-quality serial production and scale local business and establishing a strong educational platform for Zhytomyr and Ukraine as a whole.

The History of Vymiriuvach

The plant was built in the centre of Zhytomyr in 1956. After the devastation of the Second World War, authorities wanted to restore the country’s industry and produce military equipment. So they built an all-purpose factory that produced everything in demand, from ship’s radio transmitters, rocket launch control systems, and special equipment for the military, to electronic musical instruments and car control panels.

The plant ended up not only serving the rest of the USSR, but exporting to more than 40 countries. Today, the bulk of Elektrovymiriuvach’s production consists of electrical measuring devices, training kits for university students and school equipment for STEAM-laboratories and science classrooms. The plant’s products continue to be exported abroad, including the US. Andrii Chyburovskyi, the plant’s general director, explains why their products are popular abroad:

STEAM-laboratory

An innovative educational space where the learning process is based on modelling, design and experimentation.“After working with the equipment for a year, they test students and examine how they progress. Then they compare it with other schools to decide if it works effectively. And the fact that demand for our products is growing shows that they are necessary, functional, modern and high quality.”

Andrii considers it hard for Ukraine to compete with Chinese producers when it comes to production volumes and prices. So from the start of his work at the plant, he focused on transforming a solely production-oriented enterprise into an innovative one. He took up leadership of Elektrovymiriuvach in 2016. After the plant’s steep decline in the 1990s, which was followed by privatisation and staff layoffs, he was called in as crisis manager together with Vitalii Kuzmin. They were expected to lay off more people and sell off the plant’s property.

Instead, the managers reached an agreement with the then-owner to buy the plant within a few years. Andrii says that it might be more profitable to build a shopping centre or residential complexes in its place, but they decided instead to create an innovative and meaningful space for society:

“Now we are co-owners and dream of making a project that, in addition to financial profit, will also bring social benefits. This project is not only about Zhytomyr but the whole country. And if everything we plan comes through, it will be a unique project, for Europe, and for the world.”

“You don’t have to reject everything that’s old”, Andrii believes. So instead of starting from scratch, the new owners chose to combine what had accumulated over decades — the plant’s values, production approach, innovative achievements, and even its outdated but quite solid material base — with the latest trends in business, education, and industry.

Looking for like-minded people, Andrii and Vitalii turned to Roman Sakh, an architect and the creator of Ostriv (“Island”), an arts and science center in Kyiv. They sought his advice on reconstructing the facade of one of the plant’s buildings, a former tool workshop. They talked about reconceptualising and filling the free space, including with offices, but Roman pushed a more holistic approach. They discussed how simply leasing the space for offices could put the facade at risk. They decided, Roman tells us, to find another guiding motive apart from just square meters and the right to real estate:

“This was the start of a dialogue about this ecosystem, this holistic, values-driven project that unites people and creates an environment where people want to make things. We didn’t have a specific focus then. That was my introduction, my first steps with “Vymiriuvach”. We didn’t even have the name then, just a project for the facade.”

Today, there are over ten innovators working to create this multifunctional space on the factory grounds, who administer the space as well as attracting external funding. Some are from Zhytomyr, most are from Ostriv, which is based at the Kyiv National University of Construction and Architecture. The team acts mostly intuitively. Although there are examples of successful revitalisation and conversion of industrial facilities, including in Ukraine (such as Promprylad), you can’t just copy someone else’s model — you have to consider your own capacities, conditions, etc.:

“It’s about determining what unique set of ingredients you’re starting off with, in order to cook up a unique recipe. You can consult and invite experts, but it’s always a unique story.”

The first concept for Elektrovymiriuvach’s revitalization came together about a year after this cooperation began. At that time, it was only about one building. But even in 2021, three years since the project started, Andrii doesn’t have a final vision:

“For sure, we are moving in a common direction and taking the right steps. The key is not to stop. Maybe we won’t reach our initial concept — maybe it will be something much better even. But we’ll definitely reach our goals.”

The team currently has two directions picked out: education, the original source of innovation and development, and industrial production, which can still be successfully employed.

Roman invited Vita Bazan to the project in 2020. They had previously worked together in an urban development program, “Kod Mista” (“City Code”). Vita is part of Spilnokosht, a public fundraising platform for social projects, and is an expert on fundraising strategies and community development. She now helps raise funds and implement Vymiriuvach initiatives via their NGO called Kreatyvnyi Vymiriuvach (“Creative Measurer”).

“The plant is such a huge machine. It’s interesting to work out how it functions and how to transform it. Our concept is, factory as public service. Meaning, taking this Soviet factory that’s closed off like a fortress, and turning it into an open space to experiment with ideas and projects.”

The innovation park has a mixed or collaborative funding model, Vita tells us. A share of the territory is leased for a nominal fee, and the plant invests in repairs and renovations. Through the NGO the team turns to crowdfunding and works with foundations like the UNDP, Ukrainian Cultural Foundation, International Renaissance Foundation, and House of Europe. Roman explains:

“We mainly fundraise for content, events, project items, and the plant covers almost all infrastructure costs. We hope soon to start coming up with a model for self-sufficiency, at least, for some of the spaces that we have already launched. We need to work at this.”

Because some of the factory premises are still used for production, the innovative park is situated in the spaces left empty by lay-offs. At first, they just cleaned up the junk to stage events there, but now they are gradually fixing the spaces up and replacing their communications systems. But, as Andrii Chyburovskyi says, renovations and equipment are not the most important thing. The key is to develop understandable processes that attract people to the space, so that they can create and exchange ideas here. The Vymiriuvach team is creating an environment where people feel comfortable working in various areas, by arranging classes for architects, material designers and musicians, and inviting artists to take up residence.

The Sound Lab

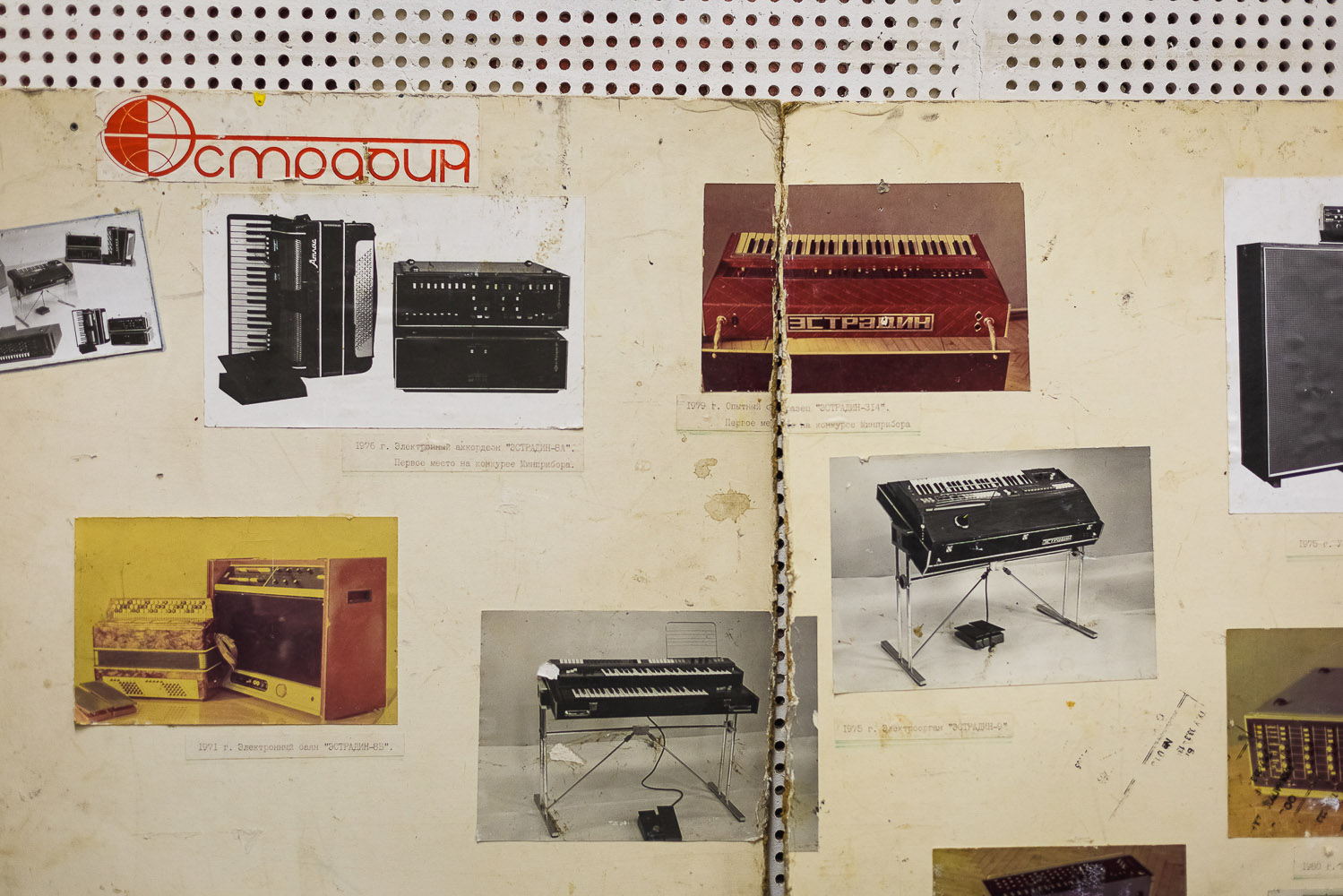

Vita Bazan says that the team uses the city as their guide for where to take the project. Several famous musicians were born in Zhytomyr (Borys Liatoshynskyi, Yuliush Zarembskyi, Natan Perelman, Sviatoslav Rikhter), and the plant itself has musical associations. Since the 1960s, Elektrovymiriuvach has produced musical instruments, including electric organs, effectors and drum machines, mixing consoles, amplifiers and reverberators. In the 1980s, a quarter of all their products were electronic keyboards. The plant staff was most proud of the Orion-084, an electric organ from the Estradin line. It was the first of its kind in the USSR and could even replace a piano and drums — a kind of organ-orchestra at the cost of a car. Even the cafe on the plant’s territory was called Estradin. This historical legacy, says Vita, led the team to the park’s first project, the Sound Lab:

“Thanks to the Sound Lab project, we are working with the fabric of the city, which was torn apart after the Soviet Union collapsed. We’ve found books, wall newspapers, so you feel this energy of progress, and that a great team has worked here. Now we have the sense that we can be independent, experiment with all this.”

The Vymiriuvach team has received equipment and illiquids for sound together with the premises for work. Having decided to work with a legacy that could be restored, they decided to develop the electronic music sector.

In July-August 2020, the team launched the Sound Lab in the form of the residence “V: UNCASE / Vymiriuvach: unpacking”. The project curator could have been Andrii Palash, but he was working on the “Konstruktsiia” (“Construction”) festival in Dnipro at the time. It was a 10-day experiment with 16 participants from multiple cities (including in the UK and Poland) living and studying at the plant, recording the sounds of machines and working on their own projects. One resident wrote an opera for electric accordion. Another student synchronised saxophone playing with the sounds made by an industrial machine during tours to the production site, and called his work “Aluminum Jazz”. Vita recalls another team’s installation:

“On the spot where the Lenin monument once stood, there is now a pedestal covered with greenery, and there’s a hole in it that goes through tothe ground. They put a projector there, shining basically nowhere, into the sky, and recorded the sounds of insects. That was a really impressive sound installation.”

The musicians also liked the high-tech pool formerly used for cooling water: they set up a concert area where performers played electronic music sets using the pool’s acoustics.

Roman Sakh explains that the project’s greatest benefit is the opportunity it provides to test a variety of formats and adapt them to the demands and visions of their target audience:

“This is an experimental platform for electronic music and an engineering workshop for analogue synthesizers. Every year we try to develop new areas to diversify our project.”

The Zhytomyr audience is familiar with electronic music. Since 2016, the city has been the site of ATOM, an international festival of experimental and electronic music held in the Serhii Korolyov Astronautics Museum, whose guests include performers from Great Britain, Germany, Poland, Hungary, and Japan. Apart from music sets and performances, the festival also features lectures on music and creative studios.

Serhii Koroliov

Ukrainian Soviet scientist in the field of rocketry and cosmonautics, designer.

The Vymiriuvach team even advised the Mayor of Zhytomyr to integrate electronic music and the engineering of electronic instruments into the city’s cultural strategy:

“Cities should have their own clear themes. And electronic music could become a specific selling point for Zhytomyr.”

In 2021, with the support of the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation, Vymiriuvach is inviting individual artists to take up temporary residence. And an international exchange project for composers, “The Rooms”, is planned for next spring, in cooperation with House of Europe: eight musicians from Graz, Austria, will explore the sounds of the Elektrovymiriuvach, while the same number of Ukrainian artists will work with sound systems in the Institute of electronic music and acoustics at the University of Music and Performing Arts Graz. The program’s participants are expected to create virtual rooms with 3D sound and 360-degree imagery.

slideshow

Vymiriuvach: The Constructor

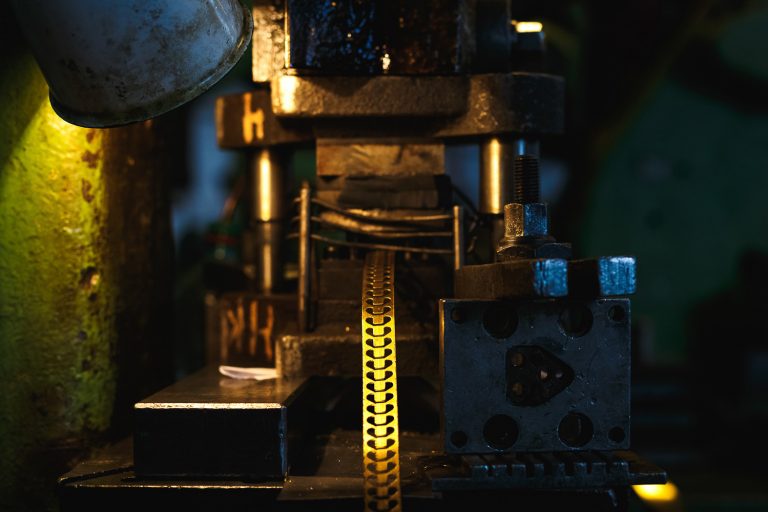

The factory’s transformation process is what defines Vymiriuvach. On the one hand, we are talking about modernising factory equipment; on the other, it’s about developing laboratories and other activities that take place alongside industrial production — not displacing what’s already there, but filling the space with new meaning. Now Elektrovymiriuvach is a place where people can learn to work with different materials and implement their ideas. Roman says that from the first days at the plant, the team felt the potential for creativity here:

“We all miss the feeling of working with our hands now. Everything has become digital, computerized — and this really affects how we create things physically in space. It affects how architects and designers conceive things — without understanding how to physically implement them. The plant has continued to produce. There are established processes and specialists here, and we can do a lot with that.”

slideshow

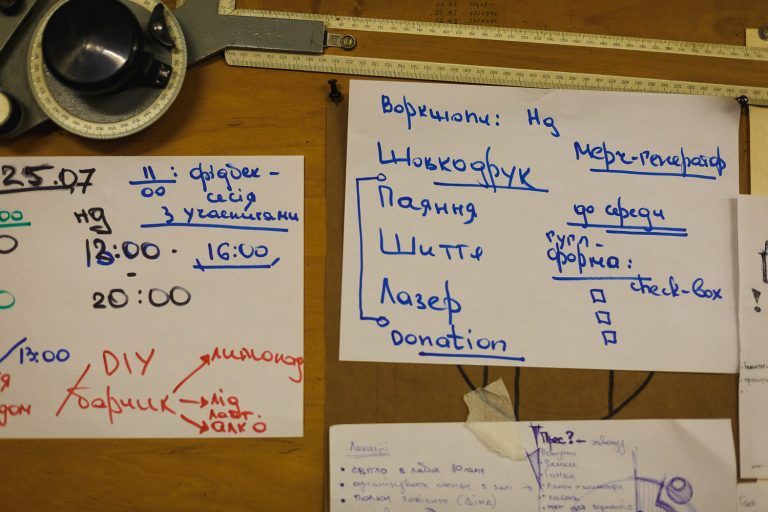

The idea came to fruition in the summer of 2021, when Vymiriuvach held its School of Material Design. Sixteen participants worked with various tools, including 3D printing, silk-screen printing, and textile and soldering equipment. While working on their own objects, residents disassembled equipment such as cameras and outdated factory products into spare parts, studied how the materials fit together and functioned in experiments, and learned new design techniques. The participants had a range of experience: some already had their own production going, while another has a specific request and needs a definite material base.

Residents often found ideas and materials at the illiquids warehouse. This is where they store materials for mass production purchased in Soviet times, which were never used due to the sharp drop-off in production. Today, most of these items are outdated and sit gathering dust at warehouses. Yet they do wonders when it comes to kindling the spark of innovation park. Roman says that following the principle of upcycling, residents disassemble illiquids and use them to make elements of decor or designer accessories.

Upcycling

The process of producing new things from things that have been recycled or previously used.“A lot of participants came to the School of Material Design with their own projects, but eventually they end up taking old parts — resistors, transistors — and using them for their models, because it’s something unique that you can’t buy in a shopping mall.”

Uliana, a resident of the School, found parts for a lamp among these odds and ends:

“Something good always comes out of nothing. And this plant is a very cool “nothing”, although it is a huge “something”. The illiquids room has all sorts of junk that’s about to be thrown away. But it’s not actually junk – so much human time, energy, and life has gone into it. I went into that room and there were some metal discs. I thought, these are pretty good, so I made light bulbs out of them.”

Roman Sakh says that schools need to, among other tasks, find a way to create interesting products with the equipment and materials available:

“The school is a means for testing multiple hypotheses that we come up with, and a source of insights that then we apply to our further work on the revitalisation of the plant overall.”

slideshow

Vymiriuvach, together with the works of the first School of Material Design participants has presented some of its workshops to Zhytomyr residents. Anyone who wants to can now develop their own product. A significant advantage of inventive work in this space is that the plant is still operating, and there are craftsmen who can advise. This project was funded in equal parts by the UN and Elektrovymiriuvach.

Vita Bazan sees the Production Lab as a way to jump over several stages of the industrial revolution: from industrial stamping, straight through to the manufacturing and testing of products designed for the needs of the consumer. It requires physical space, and the innovation park provides it:

“It will work through a system similar to fab labs and collective workshops. Craft makers, manufacturers, and designers will be able to use them to make their products, and will also have access to general production.”

Fab lab

A prototyping laboratory with easily accessible equipment; a workshop where you can make a sample of your product.

slideshow

Roman Sakh explains that the team is trying to create an ecosystem where someone who wants to make their own product can get full support: from logistics to warehouses and management, to production, technical assistance, and accounting.

“We mean to create an infrastructure where a variety of creative engineers, architects, designers and others who wish to create something will have every opportunity to further their vision, design the first test batches or prototypes, and convert their idea into something tangible.”

The Vymiriuvach team realises that not every idea will be valuable, but what counts for them is that participants gain experience and make strides in their creative development. And Andrii adds that participating in another program at the innovative park may give them new ideas. To this end, the former tool workshop will soon be equipped for presentations, exhibitions and educational events.

A gentle integration process

The first thing that impressed Andrii Chyburovskyi when he came to Elektrovymiriuvach was the employees’ commitment to their work within an enterprise of such scale:

“This was the first time I’d encountered a company with employees for whom this was the first and only place they’d worked. Some have been working here for 40 or even 50 years. This job is their life. I wanted to somehow modernise this place so that their experience could be passed on to new personnel.”

He describes the attitude of the employees as cautious and curious at the same time. The workers have seen tough times when they didn’t get paid for six months, or got compensated with factory products instead. For them, this is all an experiment in which they are involved:

“They get excited when, for example, young girls work with the welding machine — that’s a novelty for them. Their eyes light up: wow, I’ve worked here for 40 years, and I’ve never seen anything like that. They really support us, and try to help in any way.”

Andrii tries to focus on the positive points of the old culture. He says that he feels there is something to miss, and feels drawn to the atmosphere. The transformation of this spirit, he adds, is a long, complicated process, but it’s happening, and residents are showing a desire to make something here, to work. One resident, a media artist and engineer from Odesa, Ereh Saw, even opted to stay, and is now exploring the use of illiquidities and working on his sound devices.

Roman says that everyone who comes here is fascinated by textures, relics and old devices. The residency program gets a lot of applications — 3-5 for each spot. People come from Kharkiv, Odesa, and Lviv, ready to work here in less-than-ideal conditions because they value being in an environment where things are being created. In particular, they like being able to communicate with plant employees, who are proficient in design, materials, and processing methods and have played a role in manufacturing musical instruments.

“There are young workers from the design bureau who are into music and have gotten involved in our work,” Vita says. “One of them even gave a lecture on synthesizers. They’re making efforts to integrate.”

slideshow

A successful example of cooperation between residents and employees at the plant is the silk-screen printing workshop. Valentyna Kozliuk, Deputy Director of Assembly Production at Elektrovymiriuvach, curates this section within the Production Lab, helping participants with equipment and production, and giving advice on how to improve quality. She says young people often come in to get a look at how the plant works. Vita believes that this sort of collaboration is making the space a more open one:

“It’s a process of evolution: first there was one event, then another, then they took down the fence so that it’s now open here and it’s become a sort of city park. That’s better than having it sit empty, in desolation. I feel the space coming back to life, and the fact that all these tools are being used means a lot of stories are coming to life.”

For example, the Vymiriuvach team has invented code names for plant locations: “Grot” (“Grotto”), “Altanka” (“Gazebo”), “Baseyn” (“Pool”). When they say they’re holding a concert at the baseyn, they explain, they’re referring to a former fountain. Vita continues:

“We are called “astronauts” here. Once, an employee inadvertently talked to the director on a loudspeaker. He says, “We need to land Vita somewhere in the room,” and she answers him, “Oh, is this one of the astronauts?” Okay, Vita is “an astronaut”, and the whole team are “astronauts”.”

Zhytomyr residents see the plant’s revitalization as an opportunity to enter the place, where before you could get only by special permits. Vita says a mixture of people attended the Open Days in 2020 — there were the culture connoisseurs, the bohemian crowd, and then some who just wanted to peek inside a restricted object. In June 2021, Zhytomyr residents got to watch some Ukrainian New Wave films from the Dovzhenko Centre in the innovative park:

“About thirty people came to our first movie showing. It was a great audience; they stayed for another hour or hour and a half for a discussion with the film directors. People are hungry for these sorts of events.”

Lots of local youth are volunteering to help the Vymiriuvach project in various ways, like building a silkscreen workshop. Some Zhytomyr residents are eager for what comes next, some are arranging to rent workshops, and, of course, there are those opposed to change. Once, an innovation team arranged a “musical intervention”, where they played experimental music on one of the main streets, but were told, “we don’t appreciate your music, we will pull the plugs”. The head of the plant says that people are not particularly aware of what is happening there and he doesn’t want to start a PR campaign:

“We want to show real results — that’s how we’ll show people who we are. Then we’ll gradually put out information.”

Vymiriuvach. The revitalisation of Zhytomyr

Zhytomyr used to be an important centre of manufacturing, filled with large enterprises like Khimvolokno (Chemical fibres combine), the Lonokombinat (Linen combine), the Verstatuniversalmash (a plant producing machines of all sorts), the Promavtomatyka (automatics production), the Avtozapchastyna (production of car parts). Today these have been replaced by residential complexes, shopping malls, parking lots, warehouses, or just ruins. While Elektrovymiriuvach retained part of its production capacity, it lost the lion’s share of profits. Its workforce fell to 300 people, from the previous 6 thousand.

There are about 28,000 students in Zhytomyr, which is almost one-tenth of the city’s population. Despite its low cost of living, easy navigability and ecological advantages compared to Kyiv, Andrii Chyburovskyi says the city continues to serve as an “incubator” of resources for the capital, which is about 140km away.

“As soon as someone more-or-less enthusiastic and progressive appears here, Kyiv, like a huge vacuum, sucks this new talent out of Zhytomyr.”

The city could grow into a business center near Kyiv, but it the city could grow into a business centre near Kyiv (the cities are about 140 kilometres apart) needs to find new ways to hold onto its talented residents.

Vymiriuvach could be one of them. It’s due to include an education development centre, an event site, an R&D department, workspaces, green areas, and a hotel and cafe. Plus, it’s all conveniently located, within walking distance of a new business district on Kyivska Street, administrative buildings, cultural institutions, restaurants, shops and hotels. Andrii believes that thanks to both the residences and the events at Vymiriuvach, visitors from other cities will get to share their experiences, and Some may settle here, revitalising the city and broadening its intellectual scene.

To this end, the team is studying up on different topics to learn best practices, adapt them to local conditions, and search for partners. Going off to work abroad is one thing, but Andrii says he’s more interested in gaining experience abroad in order to build something at home.

“We’re discovering the whole world through our cooperation with Zhytomyr. When I started working on the project, we talked about an experimentarium, and I started searching, visited the Copernicus Science Center in Poland and discovered the field of interactive installations. Now we have a musical theme, and we’re planning to go to Austria to explore it.”

The revitalization of Elektrovymiriuvach is about developing a new socially meaningful space that meets the intellectual and production needs of the city’s residents, other Ukrainians, and foreigners. The Vymiriuvach team is trying to preserve as much as possible of what is valuable here – but to supplement it with something modern, to heighten and transform its value, reshaping it into something new.

“We’re not just building some quick, dull development, where you just clear everything away and fill the space with new commercial real estate; we’re trying to deliver some historical continuity. And this is the central idea around which the musical, educational, craft and production themes line up.”

Real estate development

Entrepreneurial activities aimed at creating or improving an object of real estate in order to increase its value.

The team shares this approach: if you can preserve something, you should preserve it; if something requires modification, it should be reworked. For Andrii, the plant manager, this is how to build a social enterprise:

“There are simple standard schemes for using downtown real estate, and a lot of offers that could provide a financial cushion for the rest of my life are still coming up now. But it’s a certain experience and vision, and an understanding of the process, that allow you to set your sights on creating something that no one’s done before.”

supported by

House of Europe is an EU-funded programme fostering professional and creative exchange between Ukrainians and their colleagues in EU countries. Implementation of House of Europe Programme is led by Goethe-Institut Ukraine with The British Council Ukraine, Institut français d’Ukraine and Czech Centres as Consortium Partners