Viktoriia and Yaroslav Knysh set up a farm and creamery in the village of Selysko, Halychyna, where they produce butter, yoghurts and cheeses from natural cow, sheep and goat milk. After their friends set up a dairy farm with Jersey cattle in Selysko, they moved to the village and began making value-added products.

Dairy products have always been an important part of the Ukrainian national diet. Until recently, the milk processing market was mostly the preserve of large companies. The situation has changed in recent years due to the growing popularity of local organic products. There are also several motivating factors for manufacturers to establish small dairy brands: the desire for independence from larger companies, the opportunity to gain a stable income from raw materials, and also to make value-added products and create jobs. Increasing numbers of entrepreneurs are establishing and developing dairy farms; many are also processing milk into sour cream, butter, yoghurt and cheese, and experimenting with flavours and original recipes.

Lviv Jersey Creamery, one of the popular manufacturers, was established by Viktoriia and Yaroslav Knysh in the village of Selysko. Their farmhouse cheeses and yoghurts are renowned not just in Halychyna, but in every corner of Ukraine. They are also sold at ‘Silpo’ (a supermarket chain with branches in over 60 Ukrainian towns and cities — tr.) under the label ‘Lavka Tradytsii’ (‘Store of Traditions’ — tr.), which also supports this series of stories about local farmers.

“I don’t have any Jersey cattle. I have cheese”

Viktoriia and Yaroslav Knysh began their journey into the business world by selling building materials. The economic crisis in 2013 forced the family to look for new ways to make money. The couple met up with their old friends, Oleh and Anna Temchyshyn, who had opened a farm called ‘Agrotem’ in Selysko and begun breeding Jersey cattle. This inspired the Knysh family to start producing dairy products.

— At first, we tried selling milk. Then we did some simple math and saw that when you process it, you get a nice bit of added value, and so we began to experiment.

Viktoriia went to study cheesemaking in Slovakia, Poland and Italy, as there were fewer study opportunities in Ukraine at the time. She was lucky enough to get a good practical grounding from Polish cheesemaker Silwester Wańczyk.

— I learned how to make my first presentable cheeses from him. He’s a fantastic person, because he didn’t hide away his knowledge — he shared all his skills. I was just working and learning. It was fantastic, unreal. So now, whenever beginner cheesemakers approach me for a consultation, I always agree enthusiastically.

slideshow

At the end of 2013, the Knysh family launched production at Lviv Jersey Creamery. The creamery is right next to the farm; the Knyshes and the Temchyshyns work together, sharing out the responsibilities for the different stages of production. Viktoriia and Yaroslav named their business after the variety of cattle that their friends breed on the farm.

Jersey cattle

A breed of cattle that originates from the island of Jersey (in the Channel Islands), known for its milk high in butterfat.— At the time it was one of the few farms in Ukraine that had Jersey cattle. It was something extremely rare. Whenever we went to a festival, people would ask if they could buy Jerseys from us. I would reply, “I don’t have any Jersey cattle: I have cheese.”

At the creamery, Yaroslav takes care of the logistics, while Viktoriia makes the cheese and processes customer orders. Besides Viktoriia, there are three employees working on the production process, all three of whom are local. Their daily workload depends on the volume of milk, which needs to be pasteurised and fermented in good time.

— We get here at 7:30am and can work till 6pm, until all of the milk is processed. We can’t leave any milk for the next day.

A variety of cheeses

There are a few main groups of cheeses on the world market, each of which contains multitudes of variations in flavour. Cheeses are usually categorised according to firmness (soft, semi-hard, etc.), age (fresh, aged for a few weeks, or for up to a year), country of origin (for example, France, Italy or Switzerland), or the type of milk used (usually cow, goat or sheep).

In the seven years since it was established, the ‘Jersey’ creamery has developed a considerable line of dairy products: butter, cream, yoghurts, plus fresh and aged cheeses.

The Knysh cheese business started with the production of sour milk cheese (or cottage cheese). Though it is one of the most popular cheeses, Viktoriia claims that it is also the most difficult to make, owing to its sensitivity to external factors (humidity and temperature).

— At one point we even wanted to give up making this cheese, but we couldn’t do it, our Halychyna traditions are too strong… People from Lviv can’t live without it.

slideshow

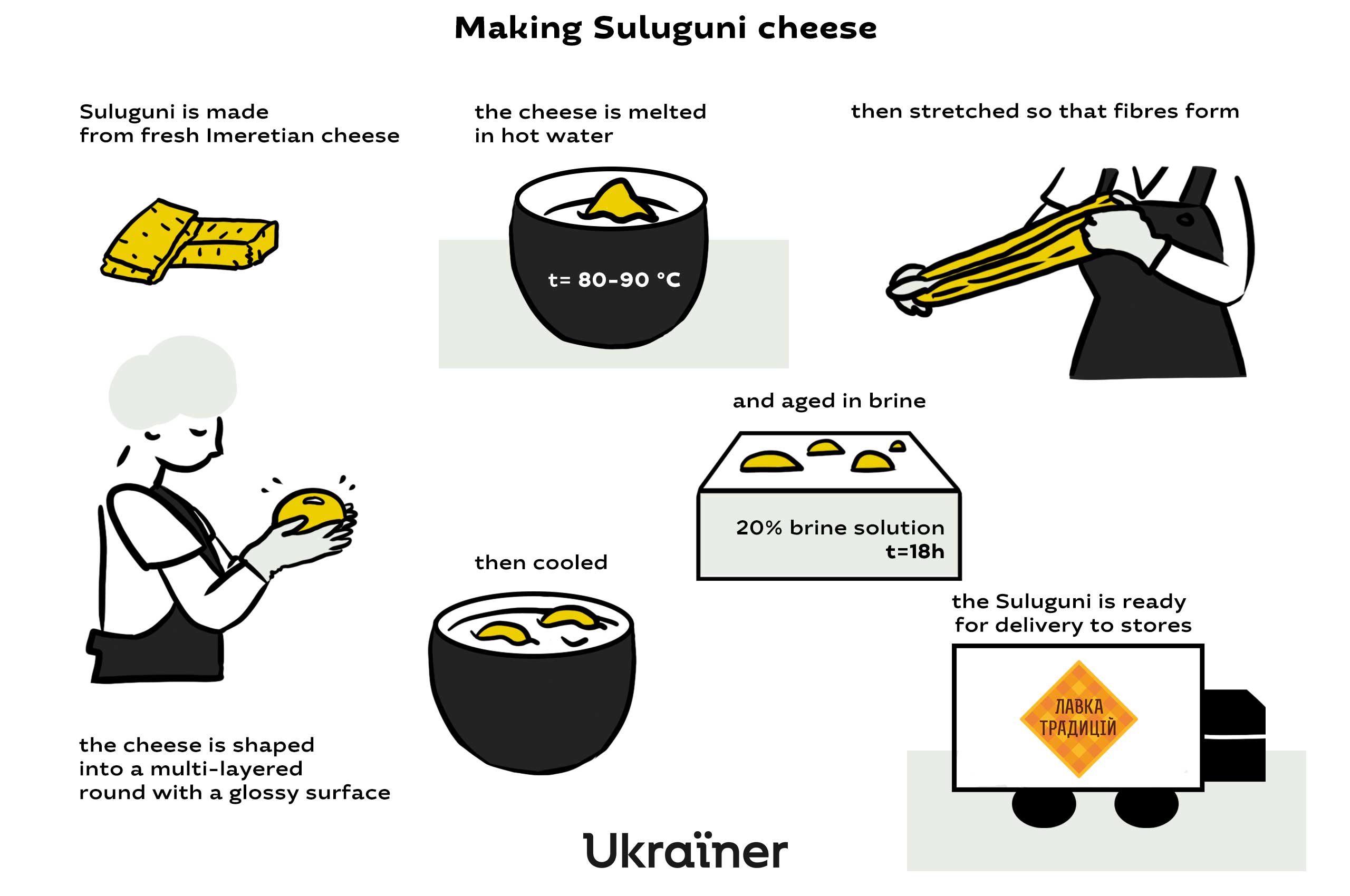

To make Suluguni (a popular Georgian cheese with a salty taste — ed.) Viktoriia prepares fresh Imeretian cheese a day in advance. It is melted in hot water, then separate fibres are formed and shaped into balls. The wheels of cheese are then cooled and aged in brine.

Imeretian cheese

Fresh Georgian cheese with a mild flavour, aged in brine.— When people ask why Georgian cheese is so expensive, we can explain. It’s all down to high-quality raw materials and hard work.

The Knysh family say every cheese requires a different approach. For example, ‘Tsisarskyi’ (Caesar — tr.) cheese, belonging to the Tomme family and made according to a French recipe, does not need to be ‘bathed’ — the mould grows by itself.

— Neither the south of France nor the north of Italy are known for pedantry or punctuality. They just put it away and go, “Ah, it’ll survive! Something will come of it!” And then their cheeses grow such fantastic ‘coats’.

On the other hand, ‘Pysanka’ cheese needs to be carefully cleaned so that on the third week of washing, the outer layer develops a reddish hue. Viktoriia explains that she does not add any colouring — the colour is derived from the activity of red bacteria (brevibacterium).

— We don’t use any artificial coating — that is, there’s no wax. That would completely change the taste. When the outer layer is edible, the flavour is totally different.

‘Premiera’ was the first aged cheese to be made at the ‘Jersey’ creamery. According to Viktoriia, it is a very unstable type of cheese.

— There were times when we’d come back to the storage room after the weekend and the cheese was gone. But how? Where did it go? Onto the floor: it’s leaked through all the racks. Basically, it’s a runny cheese.

Of the Italian varieties, the family makes Sicilian caciocavallo and calls it ‘Hrushka’ (‘pear’ in Ukrainian — tr.). It is a semi-hard cheese from the ‘pasta filata’ family (stretched-curd cheeses — ed.), shaped like a pear and matured for a month and a half.

While producing the cheese they call ‘Voloshka’ (‘cornflower’ in Ukrainian — tr.), they make special cuts and holes that allow blue mould to develop. This is added in a dry state, along with yeast. As blue mould spreads aggressively, these cheeses are produced separately from all the other aged cheeses.

From the classic Dutch cheeses, the Knysh family produces ‘Svejk’; from the range of Swiss cheeses, they make ‘Monte’. Viktoriia rubs these cheeses with a brine-soaked brush.

She points out that even when following the classic recipes, it is impossible to produce cheeses that are identical to the French or Italian versions, as everything else is different: the Ukrainian cows and grass, and the overall maturation conditions. The Knysh family do not produce Parmesan or Emmental, as Jersey milk contains more fat than those recipes require.

— We aren’t trying to make an absolutely perfect copy of the classic foreign recipes. We add something of our own, we adapt them according to the local milk.

Cheeses can also vary in flavour and texture depending on the weather. This creates one more way to categorise cheeses: by season. Winter cheeses are higher in fat and protein, whereas summer cheeses are lighter because cows eat fresh grass during the summer months.

The subtleties of production

Despite the variation among cheeses, the basic production processes are very similar. The milk is heat-treated (pasteurised), cooled, and standardised (when the cream is removed, to be used for butter). The cheese curds are formed when yeast or rennet enzymes are added to the milk. Later, the curds are pressed and made into cheese wheels. Some cheeses require two days for the whole process, while others need over six months.

Viktoriia says that the most critical task in cheesemaking is cutting the curd. At first, it is detached from the edge of the basin. To cut it, a special curd knife is used. If cut at the wrong angle, the curd can break.

However, the most important part of cheese making, according to Viktoriia, is the maturation, or affinage. She calls the maturing room “the heart of any creamery”.

— When the cheese is put away to mature, a kind of magic begins. Because you’ve got to dance for it, talk to it, and in the end, you’ll get a nice result.

Viktoriia says that the maturing room already has its own ecosystem. She buys all of the necessary types of mould and yeast, which are used in the dry state.

— They (the bacteria — ed.) grow by themselves due to the humidity, and here they already have the environment they need.

If you put cheese into a newly built room, the process will be long and complicated. The cheese would need at least three or four months to mature there.

slideshow

The couple started making yoghurt much later on, as this process requires basic knowledge of milk microbiology. Viktoriia already has two degrees (in applied mathematics and law) and has begun studying this field by herself.

— I had to pick up my books again and go back to online classes. I’m studying microbiology. You never know where your path will go, and what you’ll learn there.

Yaroslav Knysh is responsible for smoking some of the cheeses: this is how he makes Scamorza and Chechil. Yaroslav smokes them on oak chips for about 12 hours. In the morning he checks to see if the cheese has a golden tint. If not, then the smoking continues.

— It’s naturally smoked, with no liquid smoke or any other mischief. Everything is transparent.

Milk: the secret to success

According to Viktoriia, the most important element for a cheesemaker is high-quality milk. It has to be flavoursome, without any unusual odours or aftertaste; above all, it cannot be sour. To make one kilo of cheese, the Knysh family use about 10 litres of milk. In one summer day they process one ton of milk; on a winter day, it can be as much as three tons.

— I set us a limit of 40 tons per month. When we increase production, we lose in quality. When we say that quality is what we’re after, we’re not just showing off. Our customers point out all of our mistakes. We repent like sinners, reduce our production volumes, and keep an eye on the quality.

The milk from the Temchyshyns’ farm arrives in a special milk truck. It is then poured into a receiving basin, before being distributed according to the cheeses to be made that day. There are three options: milk standardisation, pasteurisation (for aged cheeses), and bottling.

The ‘Jersey’ creamery is popular not only for its cheeses, but also for its farmhouse butter. Just as for cheese, the colour and taste depend on the weather conditions: in summer it is bright yellow, while in the winter the colour is lighter.

— Don’t put anything nasty in the cream and you’ll get perfect, amazing butter! Plus, when you factor in the nice grass outside, you’ll get the results that we have.

slideshow

Anna and Oleh have Holstein and Jersey cattle on their farm. The mixture of the two types of milk makes the ideal raw material for cheese. According to Anna, the Jersey cows produce high-fat milk (4-6% fat), unlike the Holstein cows, which produce a higher volume of lower-fat milk. When mixed together, the proportions are just right.

— We need to clearly understand what digestive processes are going on in the cows’ stomachs, and how that affects the milk. For example, some cows eat a lot of clover, which is rich in propionibacterium. This helps to form nice big holes in the cheese.

In addition to cow milk, Viktoriia also makes cheese from goat and sheep milk. She experimented most of all with sheep milk:

— Very few people had worked with it before in Ukraine. So I came up with all the recipes for our sheep milk cheeses. In reality, they were all wild experiments based on my prior knowledge, and they turned out well.

As of summer 2020, there are 90 cows on the ‘Agrotema’ farm, compared to just five at the beginning. The cattle are constantly looked after, and have a balanced diet. The main ingredient in their feed is alfalfa, or else unthreshed barley or rye. Anna and Oleh aspire to make their family farm production fully organic.

— I think that the farms of the future will be the ones with a continuous full cycle, where cattle are raised, crops are grown, and products are made. You could say that a farm like that has all the steps, from the embryo to the end product.

What’s next?

‘Jersey’ often takes part in farmers’ markets; they also have a few of their own stores in Lviv, and want to open their own tasting centre. The creamery has already received several awards at the Ukraine Cheese Awards Day, and in 2017 they won a special prize: a trip to Italy for a cheesemaking workshop.

The Knyshes and the Temchyshyns often plan trips abroad together, during which they visit creameries and cheese exhibitions to gain more experience and put it into practice at home. Anna Temchyshyn is convinced that Ukraine has strong agricultural potential, which is why she is so keen on developing her own business here.

— We went to Italy for a cheese exhibition. Every country was represented there except for Ukraine. And so the four of us got together and said, “One day we will represent Ukraine at an exhibition like this, with our craft cheeses, and our quality will be equal to all the rest.”

Jersey Creamery, Temchyshyn Farm and a number of other farms have joined the “GorboGory” agritourism cluster, created to promote regional products and increase the region’s tourist attractiveness.

I believe that farms like this are the farms of the future, with a continuous cycle of raising animals, growing crops, and making products. Villages will develop accordingly. You could say that Selysko is becoming increasingly well-known. We have Skarbova Hora as our lovely neighbours. There is also a winery nearby, they make raspberry wine. So we’ve got cheese, wine and a place to relax and have a good time.

Victoria says that her priority is stable product quality and a satisfied customer. After all, behind every head of cheese or a bottle of yogurt is a brand, and the founders want people to love it.

This is our lifestyle now, this is our hobby. We like it. We really do. Well, we came to cheesemaking pretty late, but I understand that we’re in the right place. We’ve finally found what we enjoy, the work we like. I’m happy, I feel great. I just really like it. It’s fantastic.