The Soviet Union, the largest totalitarian neo-empire in the world, collapsed more than three decades ago. However, a generation of older people who lived in the USSR still recall (or re-imagine) it as a haven of solace and peace. It’s easy to see why: when they were younger, everything seemed more upbeat. As a result, they spread the myth among modern youth that life in the USSR was as good, if not better than life today. This concoction, based on ideological stereotypes about social welfare and comforts in the era of “stagnation,” warrants deeper examination.

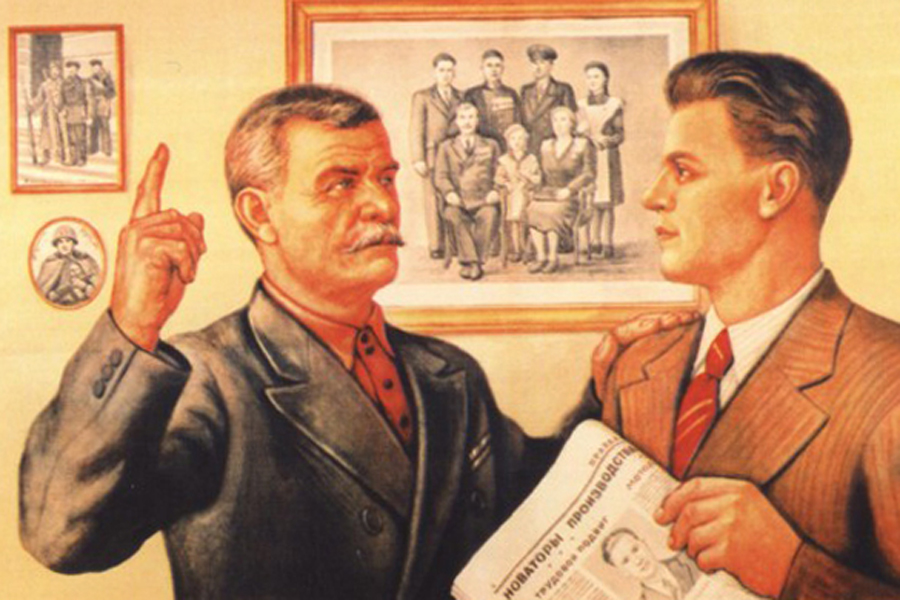

Constructed by the Soviet system, the “golden age” myth was irrefutable as people behind the “iron curtain” couldn’t compare their living standards to those of other countries. The rest was accomplished through censorship and propaganda, which served to glorify the regime by preventing criticism. Leonid Brezhnev’s rule was particularly influential in shaping the narrative of the USSR’s greatness and the superiority of the “Soviet way of life and values” over those in the West. The human factor also plays a role in the current spread of Soviet myths. Decades later, the flaws of everyday life appear less relevant, if not completely forgotten.

Quotidian Life of the “Soviet Man”

Following WWII, that is, during the Cold War, the Soviet Union based its entire existence on “outrunning and outdoing” Western countries, most notably the United States. Most of the time, such ”outperforming” was showcased by complete absurdities, such as melting more cast iron than the United States, regardless of the actual need or efficiency of time spent on such an effort. Another example is the Space Race, which transformed scientific research into a technological confrontation between two countries.

However, it was in the area of living conditions for its own citizens that the Soviet regime constantly backslid. There is a wealth of reasons for this situation, but the main one is that the military-industrial complex received the lion’s share of the revenue generated by the sale of energy carriers to support the dictatorships and partisan movements in “third world” countries. The USSR’s social sphere came as an afterthought. As a result, the daily lives of the Soviet people and their needs such as housing, food, clothing, medical services, educational services, entertainment, etc. were put aside for constant Third World War preparations and attempts to dominate the global stage.

Third world countries

A Cold War era political term for countries that belonged neither to the Western world nor to the Eastern bloc.

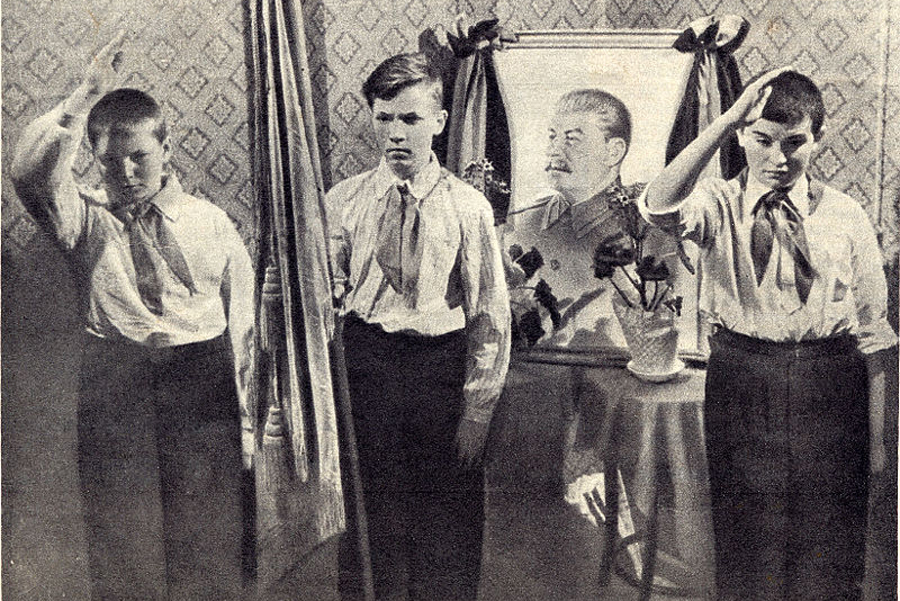

After the death of Joseph Stalin, the situation, albeit little by little, changed for the better. During Leonid Brezhnev’s rule (1964–1982), the Soviet people reached their highest level of well-being. Mikhail Suslov and other Soviet ideologues attempted to cement these welfare indicators into the so-called “developed socialism,” commonly known as “sovok.”

In 1976, at the 25th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Leonid Brezhnev spoke for the first time about the “Soviet way of life.” According to the general secretary, he envisioned “an atmosphere of true collectivism and camaraderie, cohesion, a friendship of all the nations and peoples of the country, which is getting stronger every day, moral health that makes us strong and stable—such bright boundaries of our way of life, such great conquests of socialism, which have become part of our flesh and blood.”

What was it like to live the “Soviet way”? Was everything as good as it is sometimes claimed? Let us consider in-depth the various aspects of life and service spheres that Soviet people encountered daily.

Internationalism and friendship of nations

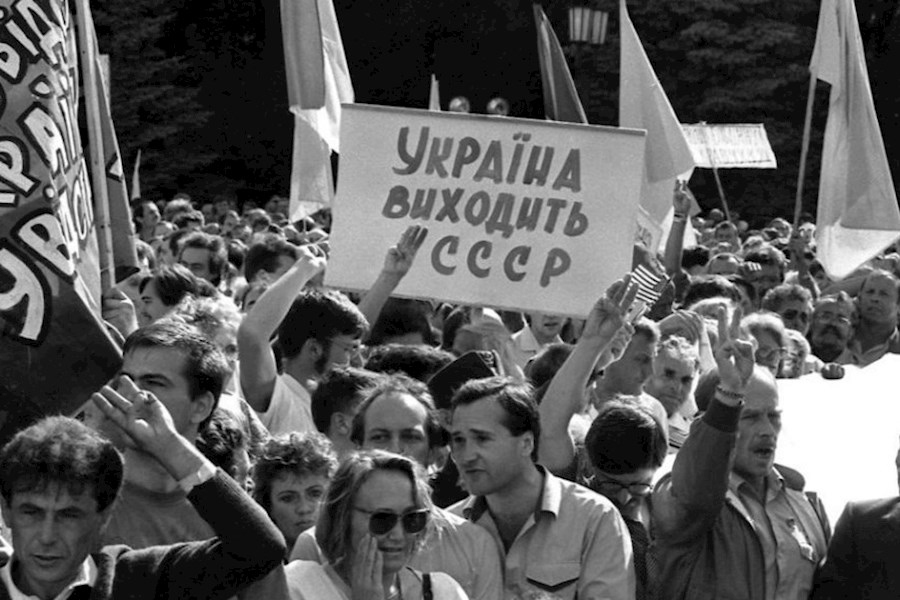

The so-called principle of “proletarian internationalism” was a key tenet of the Soviet propaganda machine. The Soviet authorities used it to demonstrate that fifteen separate union republics and over ten different autonomies could coexist within the same unit without interethnic conflicts, xenophobia, ethnic harassment, and chauvinism which allegedly did not exist in the USSR. And it makes no difference what a Soviet person’s nationality or race was because the Soviet Union was a country of internationalism and friendship of peoples.

In reality, the situation was radically different. The Soviet Union’s leadership was responsible for implementing xenophobic policies that were later adapted and carried on by modern Russia. Following Stalin’s mass deportations of so-called “small nations,” primarily Crimean Tatars, some were allowed to return to their permanent residences only in the 1950s. However, even after returning from deportation, people were not shielded from state restrictions and oppression. There was, for example, administrative police supervision. People who de facto returned home following forced relocation had to keep the district policeman up-to-date on their whereabouts.

There were also many unspoken restrictions. For instance, representatives of deported ethnicities were barred from learning certain specialties. To be admitted to the Tambov Higher Military Aviation School, the future president of Ichkeria, Dzhokhar Dudayev, had to indicate in his documents that he was “Ossetian,” which was the “right” nationality in the eyes of the party leadership, as opposed to the “wrong” one which was “Chechen.”

Mustafa Dzhemilev, the leader of the Crimean Tatars, recalls a similar story. After finishing school, he intended to enroll in the Department of Oriental Studies at the Central Asian State University, but the head of the department of Arabic philology explicitly stated that Dzhemilev would fail the exams because Crimean Tatars were unwelcomed there. Mustafa Dzhemilev, who later became a political activist and human rights defender, described the policy as follows:

—That is why there are many construction workers, doctors, engineers, and teachers of Russian language and literature among the Crimean Tatars, but few journalists, historians, and lawyers. It was strictly forbidden to enter military universities.

Furthermore, in the 1960s, a campaign was launched in the USSR aimed at “fighting against Zionism.” (Zionism being a movement of European Jews seeking to establish a Jewish state. — Ed.) The reason behind this was the political crisis in Soviet-Israeli relations. Under the guise of anti-Zionism policy, the party leadership engaged in anti-Semitism. Being Jewish meant being blacklisted or banned from traveling abroad. There was an unspoken prohibition against Jewish applicants entering, for instance, mathematics majors at the country’s largest universities. The Anti-Zionist Committee of the Soviet Public was an institution that spread anti-Semitic propaganda. Ironically, David Dragunsky—a Jewish KGB General—was the one who led it.

Committee for State Security (KGB)

The USSR's state administrative body, whose main responsibilities included intelligence, counter-intelligence, combating nationalism, dissent, and anti-Soviet activities. In the Russian Federation, the FSB (Federal Security Service) became the legal successor to the KGB.

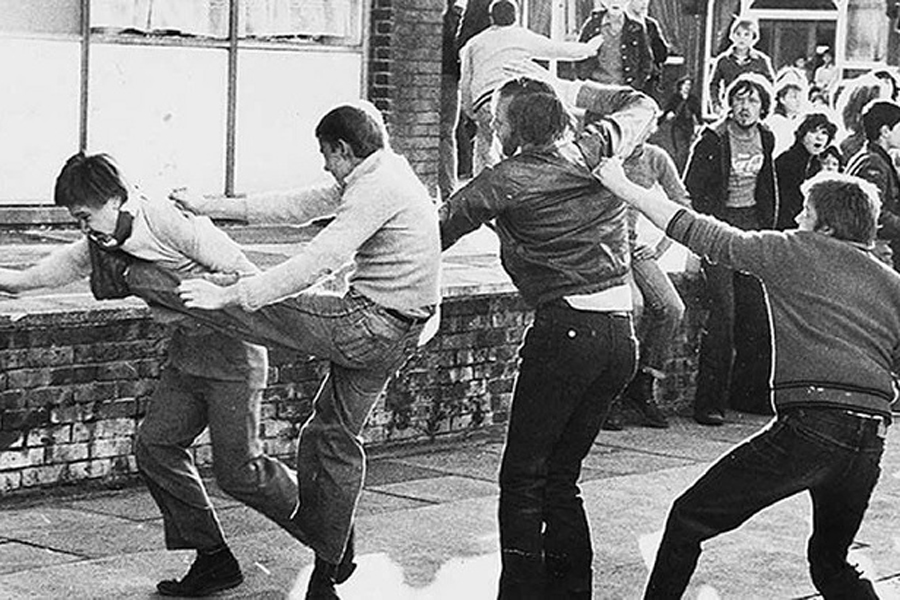

Aside from state-backed chauvinism, the USSR had significant problems with international relations, which occasionally resulted in mass riots. The truth is that the national factor was often disregarded during the USSR’s administrative-territorial division, that is, the formation of its socialist republics and autonomies. As a result, representatives of one nationality could find themselves in the national autonomy of another republic. Overlooking national conflicts was common in the Soviet army, which organized its conscript soldiers into nationality-based compatriot units. This practice often led to interethnic conflict.

Aside from the Union’s Armed Forces, such conflicts didn’t bypass civilian life either. For example, in 1981, in the North Ossetian city of Ordzhonikidze, there were mass fights between Ossetians and Ingush people who had previously returned from deportation. The slaughter that resulted in one killed and hundreds injured lasted from October 24 to October 26, until it was suppressed by internal troops and police.

In December 1986, a protest in Kazakhstan’s largest city, Almaty (formerly known as Alma-Ata), led to mass riots and casualties. The demonstrators, mainly Kazakh youth, demanded a Kazakh to lead the Kazakh Republic. The reason behind the demand was their concern that a leader of any other nationality would exacerbate the Russification and oppression of their people.

However, one of the most emblematic events occurred in 1989, near the end of the USSR’s existence, in Zhanaozen (formerly known as Novyi Uzen, Kazakhstan) and Fergana (a city in eastern Uzbekistan). In the first case, a fight between Kazakhs and Caucasians at a disco escalated into an international conflict (July 17-28), resulting in human casualties. Later, heavily armored vehicles were used to suppress the fighting. Rooted in the interethnic conflict between Uzbeks and Meskhetian Turks, the Fergana pogroms, initiated by a domestic quarrel, resulted in 103 deaths and over 100 injuries.

Free Housing

Free housing is one of the central myths of the USSR’s “golden age.” The myth: unlike the unfortunate American workers forced to pay mortgages their entire lives, the Soviet government provided free accommodation for its people.

One of the fundamental rules of economics does not exclude socialist countries: if something is distributed for free, someone has already paid for it. Therefore, not only the cost of the “free housing” was indirectly reimbursed by the USSR’s citizens, but it was significantly higher than what Americans paid for their mortgages. The Soviet leadership repeatedly stated its inability to provide individual housing to everyone.

If a person did not work in law enforcement or the party apparatus, she had to be “in a queue” to get a flat from the state. The waiting time has ranged from a few years to several decades, with some people dying before reaching their turn in the queue.

The Soviet people also couldn’t choose the district, floor, or number of rooms in the provided apartment. As a result, a new type of corruption appeared, which included “bargaining” with relevant authorities in order to obtain a better apartment in a shorter time.

However, even after receiving the accommodation, it did not belong to a Soviet citizen, as it remained the property of the enterprise or institution that provided it in the first place. Essentially, it was perpetual-lease housing that was impossible to sell. It led directly to the “exchange”—the USSR’s second unique economic relations format—that allowed people to swap their houses. Sometimes this process required additional steps, like creating a whole chain of the participants in different cities throughout the country. Such practice was easily ruptured when one of the “links” decided against participation in the exchange.

The USSR ensured mass housing construction by levying high taxes on ordinary Soviets and purchasing finished goods from state-owned enterprises at little to no cost. Strongly resembling a serf system, this complex approach was acceptable to many people in the 1960s–1980s because the majority of them had previously lived in dormitories and communal apartments. After all, did the Soviet man have a choice?

The “communal apartments” phenomenon rose to prominence in the 1920s and 1940s, when Vladimir Lenin and later Joseph Stalin attempted to create a “new Soviet man” free of “bourgeois prejudices” such as comfort, individualism, or a need for privacy. Living under the same roof with strangers and sharing a kitchen, toilet, and other rooms was supposed to foster a sense of community in Soviet citizens and “wean” them off the concept of private property.

During WWII, the situation deteriorated tremendously: people lived in attics, basements, storage, and utility rooms. People had to build barracks, dig dugouts, and make shelters out of non-residential buildings like sheds, warehouses, and storerooms. As a result, when mass construction of low-quality and small-sized housing began during the rule of Nikita Khrushchev (1953–1964), people saw it as both a gift from fate and the state even though accommodations were not entirely private.

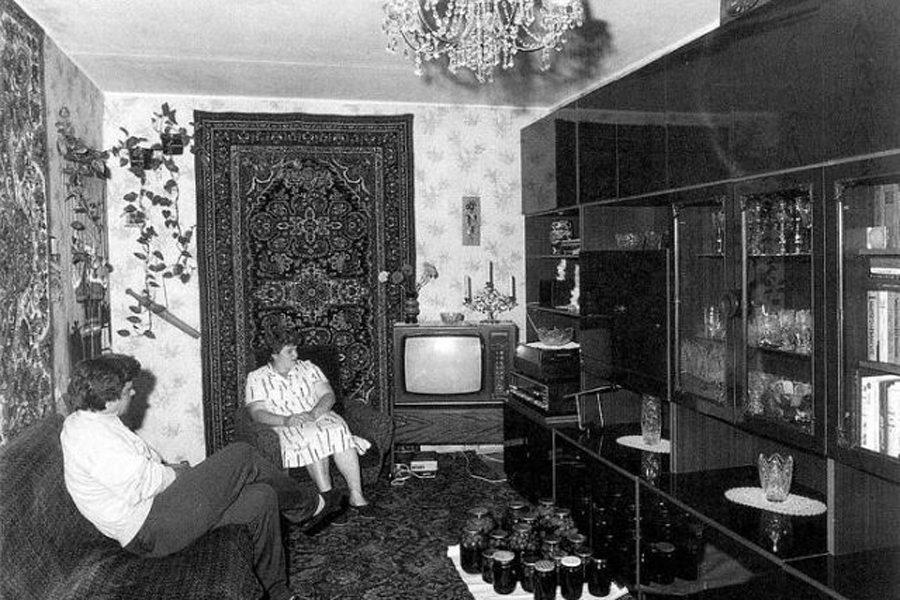

The appearance of the so-called “brezhnevka,” also known as”uluchshonka” (from Russian “improvement”), changed the housing situation. It was a larger residence with elevators, garbage chutes, separate bathrooms, and better layouts that was much more difficult to obtain than an average “khrushchevka.” In fact, since the 1970s, the Soviet people have finally begun to grasp the concept of individual comfortable housing. Simultaneously, the consumer ideal of a Soviet resident was formed, which included a wardrobe set, armchairs, sofa, kitchen cabinets, TV, and refrigerator. As these household items were expensive and in short supply, people spent a long time saving money before standing in long lines to purchase at least one of these items for their houses.

Affordable Education

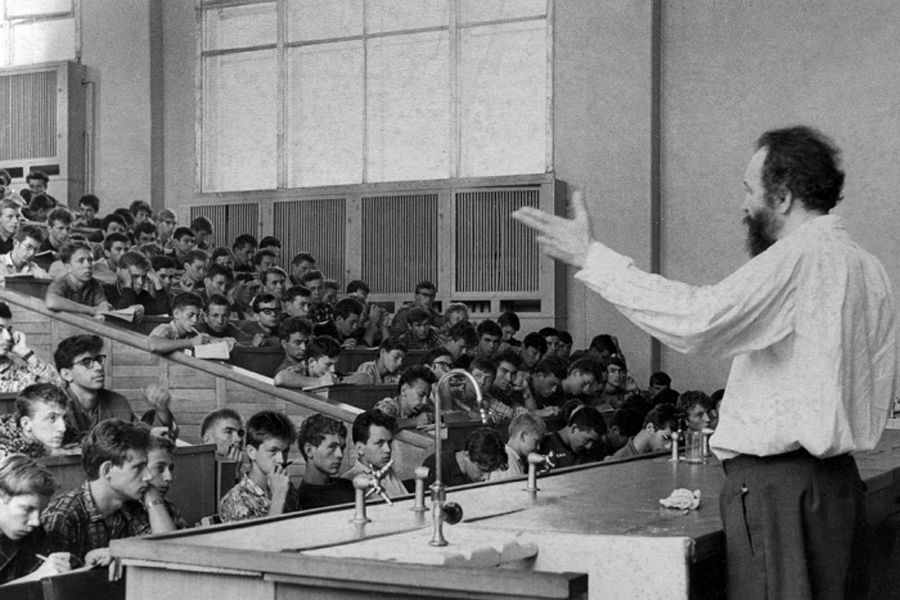

The USSR’s second most widely held myth was that it provided the most affordable education in the world. At the outset of its existence, the Union did conduct a massive campaign to eliminate illiteracy, resulting in a high level of literacy among the population. However, a closer examination of the entire educational system in the USSR (especially higher and professional education) raises many questions.

To begin with, the transparency of the university admissions process was questionable at best. The applicant had to pass the exams administered by the educational institution’s commission. There were no rules regarding objectivity or corruption risks. Due to the fact that the majority of the exams were oral, any applicant could be “failed” or “greenlit.”

Students with written referrals from political parties or Komsomol organizations received priority admission consideration. As part of the so-called “distribution,” any educational institution graduate was required to work for at least two years anywhere the university sent him. Moreover, a Kyiv educational institution’s graduate could be easily sent somewhere to Central Asia or the Far East. It indicated that education was not free; people still had to pay for it, but in a different manner.

University education was ideologically constrained. Students of all specialties from mechanical engineers to conductors studied subjects like “CPSU History” and “Marxist–Leninist Philosophy.”

Students’ education in technical and natural sciences was entirely dependent on state orders for defense items and the Union’s planned economy, while the humanitarian specialties such as philosophy, journalism, and history were on ideology and party politics. The Soviet Union appears to have taken and applied literally Nobel laureate Ernest Rutherford’s adage that science is either physics or stamp collecting. Soviet science had to meet the needs of the state, primarily in the military-industrial complex, while humanities were allegedly unimportant to the life and development of society. For instance, the humanities researchers were generally viewed as “ideological workers.” This idea affected everyone who was somehow connected with the humanities: teachers, lecturers, museum workers, librarians, archivists, journalists, critics, etc.

World’s Best Healthcare

Another myth about the USSR is that it provided world-class free medical care. The medical system, established in the 1930s by the People’s Commissar of Health Nikolai Semashko, provided the USSR’s most remote regions with medical personnel. His reforms resulted in the network of urgent care stations. However, by the 1960s, such an approach had resulted in an overabundance of medical workers and hospitals of questionable quality. Most medical personnel lacked training, had limited access to medical advances, and occasionally practiced alternative medicine that could endanger patients even more. Furthermore, some drugs were in short supply, a reality noticeable during epidemics or natural disasters. Soviet medicine used outdated equipment, reusable needles in syringes, and ineffective local anesthesia.

There was a significant disparity in the number of hospitals in the USSR’s western and eastern regions. It was due to the Soviet Union’s intention to go to war with the collective West, so the approximate front-line area had more hospitals. There was nothing there except an abundance of hospital cots. The provision of beds was a center of the Soviet medical institutions’ management philosophy; medical service quality was rarely mentioned.

According to some claims, the World Health Organization once regarded the Soviet health-care system among the best in the world. There is no evidence to support this assertion. However, one thing is certain: Soviet medicine was unable to assist cancer patients, as evidenced by the Chornobyl nuclear power plant accident (April 26, 1986), when many people received large doses of radiation and developed related diseases.

No Crime Myth

Many revisionists believe that the Land of the Soviets had the most honest police and the lowest crime rate. The crime rate in the 1970s was lower than in the United States, but it was also higher than in most European countries.

At the same time, the USSR faced the same issues with public security as the rest of the world. There were serial killers in the Soviet Union as well – one of them was Andrei Chikatilo. According to various sources, a Rostov teacher murdered between 46 to 53 people (predominantly women and children) between 1982 and 1990. Chikatilo not only raped but also ate his victims.

Anatoly Slivko is another notorious Soviet mass murderer and pedophile. As the organizer of a camp for kids from low-income families, he was in high regard in his hometown in the Stavropol Krai. He recruited boys between the ages of 10 and 15 for a “secret mission.” Instead, he sexually assaulted and strangled them (sometimes to death). Between 1964 and 1985, he murdered seven boys under the age of 16.

Vasiliy Kulik, dubbed the “Irkutsk murderer,” preyed on children and pensioners between 1982 and 1986. Kulik used his official position (as a district doctor) to break into apartments to rape and kill his victims. In total, he murdered 13 people.

Juvenile delinquency was also widespread in the Soviet Union. In the 1980s, teenage gangs known as “runners” operated in Kryvyi Rih, killing at least 30 people. Youth gangs known as “lyuberiv” (from the name of the city, Lyubertsy) were involved in robberies and street crime. In the 1970s and 1980s, Kazan had a dozen teenage street gangs committing violence for no particular reason. The “Tiap-liap” gang is perhaps the most well-known. Not only did they engage in massive street fights, but they also looted settlements, and used weapons including firearms.

Terrorism was also a part of Soviet life. Iin 1988, five attackers hijacked a bus carrying children in Ordzhonikidze (Vladikavkaz) and demanded the right to flee the Soviet Union to Israel.

However, there is a reason why many people recall the image of a trustworthy Soviet policeman. This is the result of meticulous and well-planned propaganda by the Soviet Ministry of Internal Affairs. Nikolai Shchelokov, the department’s longtime head, did not hesitate to finance films about honest Soviet police officers. TV shows like “Investigation Led by Experts” were popular among the Soviet people. Furthermore, the traditionally lavish Police Day Concert, broadcast on television, contributed to the positive image of Soviet law enforcement.

However, the conduct of the Soviet police did not always correspond with official propaganda. The lawlessness of police officers was frequently the source of mass riots in the country. In 1961, in the town of Murom, after a drunk factory worker Yuri Kostikov injured himself on the street, the police took him to the station without providing medical care, resulting in his death in a prison cell. In the same year, similar incidents occurred in the city of Beslan.

In 1968, the city of Nalchik witnessed mass pogroms and a mob trial of a police officer who illegally detained a person. In 1972, mass riots erupted in Dniprodzerzhynsk (Kamianske) as a result of police negligence, resulting in the deaths of three detainees.

A Culture of Eternal Values

The USSR’s nostalgics like to emphasize that the Soviet cultural product used to have “basic moral values,” while today, it is mainly destructive and vulgar.

However, propaganda played an important role in Soviet cultural content. There were artistic councils that served as censors and barred many artists’ works because they were “ideologically harmful.” Such censor gave rise to phrases like “put the film on the shelf” and “to write into the drawer,” which meant writing without publication prospects. Any allusion to ideologically hostile Western culture was deemed “harmful.”

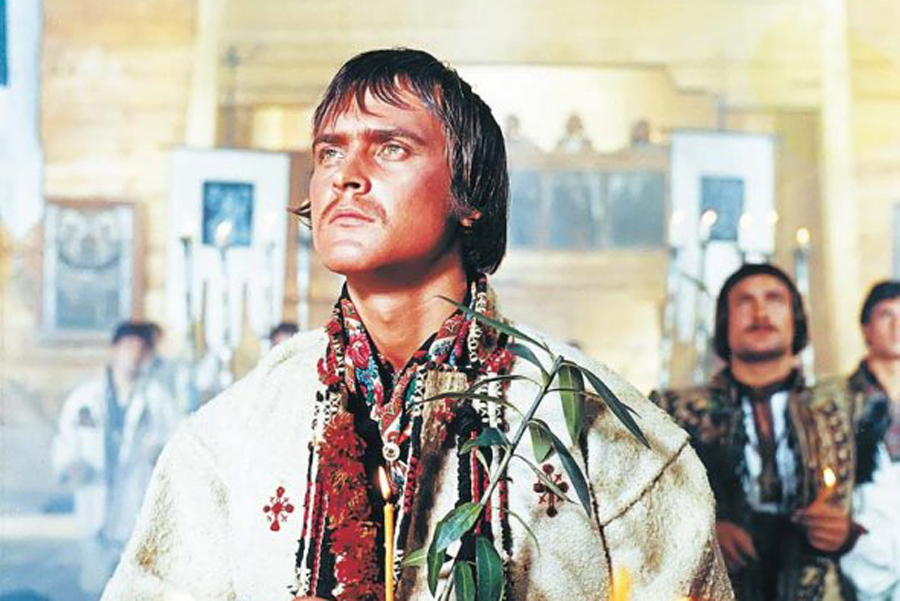

There were numerous instances of censorship. The attitude towards the figures of Ukrainian poetic cinema was indicative. For example, Serhii Paradzhanov, the director of “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors,” was initially banned from making films due to his “lack of ideological convictions.” When it became clear that the director had failed to “learn” his lesson, he was sentenced to five years on false charges. The Soviet nomenclature labeled Ivan Mykolaichuk, who played the leading role in “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors,” as “politically unreliable” for his discussions about the distinction between patriotism and nationalism. As a result, the actor was barred from playing lead roles, and the films he had already completed were released much later. Filmed in 1972, “The Lost Letter” was released eight years later.

Yurii Illienko, the cameraman of “Shadow of Forgotten Ancestors,” suffered a similar fate. For example, the Soviet nomenclature halted his “To dream and to live” 42 times at various stages. Soviet authorities banned eight of Illienko’s ten films.

Literature experienced a similar fate. After being blacklisted in 1972, Lina Kostenko couldn’t publish her collection of poems “On the banks of the eternal river” until 1977. Her verse novel “Marusia Churai” was published six years after she wrote it in 1979.

If we accept the premise that culture fulfills a specific social function including value-oriented education, encouragement of development, and nonviolent communication, then Soviet culture, through artistic depletion and censorship ideologically confined its citizens.

Delicious and Healthy Cuisine

One of the most amusing Soviet myths involves food. Apparently, all products were cheap and of high quality because they were manufactured under a single state standard, also known as GOST.

The majority of Soviet public catering dishes were recreating 1930s American advances. Anastas Mikoyan, People’s Commissar of the Food Industry, personally traveled to the United States to purchase food industry technologies. Mikoyan was a food industry expert; many of the standards he established, such as the Soviet equivalent of ice cream or a semi-finished hamburger patty, were often of high quality. By the 1950s, however, the standards had shifted: the all-meat Mikoyan cutlet began to include bread as an ingredient.

Another intriguing principle of the Soviet public catering system was the preference for steamed food and restrictions imposed on the use of spices. Manuil Pevzner, a Soviet cooking ideologue, followed a diet because of his stomach problems, so all Soviet citizens were required to follow it too. There was plenty of room for a middle ground between tasty and healthy food, but no one seemed interested in culinary variety.

In general, beginning in the 1950s, the Soviet state standard for food products began to allow the use of many chemical elements, primarily preservatives, emulsifiers, and dyes. The legendary sausage, which costs 2 rubles and 20 kopecks, was smoked using a technology involving harmful turpentine residues. Moreover, all Soviet standards for public catering in schools, military units, penitentiaries, and medical institutions have not been reassessed since Stalin’s time.

Amid constant food shortage, the “recommendation to all housewives of the Soviet Union” — the universal culinary collection “The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food” (supervised by Anastas Mikoyan) — appeared particularly insulting. The recipes often required scarce products like fresh fish or hard cheese or generally unavailable ones like cinnamon, salami, or cream. Among the Soviets, who mostly ate low-quality products and cheap meals from their enterprises or institution’s canteens, this book was considered an internal joke about what their diet should be. It’s worth noting that the cookbook was published between 1939 and 1997. The Moscow publishing house decided to reissue this supposedly universal collection 19 years later.

Nostalgia for the Soviet past is not solely a Ukrainian problem; other countries that once belonged to this totalitarian neo-empire also suffer from this. It is founded on two main pillars: memories of youth, when everything seemed better, and echoes of powerful Soviet propaganda, which passed wishful thinking as reality.

There was no comprehensive anthropological or cultural study of Soviet reality from the 1950s to the 1980s accessible during Ukraine’s independence, which would have helped to analyze and refute the existing myths and clichés. There is a scarcity of such content in Ukrainian infospace, which is why the older generation still yearns for a “better Soviet life.” Memories that appear innocent at first glance consolidate Soviet mythologemes over time, and more importantly, they become a support for the ideas of modern Russia, which adopted many colonial practices from the Land of the Soviets. Russia will try to impose “a beautiful common life, as it used to be” on all previously colonized nations for as long as it exists. Rethinking and debunking Soviet-era myths is not only a sober assessment of the USSR’s history but also a matter of modern Ukraine’s national security.