Today, the Ukrainian Bulgarians are one of the largest communities that once migrated to the lands of present-day Bessarabia, Tavria, Pryazovia, and Prychornomoria. Together with the Albanians and Gagauzes, they founded many settlements where they now live compactly, speak numerous dialects of the Bulgarian language, and preserve their own culture.

The vast majority of Ukrainian Bulgarians live in Bessarabia. The largest Bulgarian village of Bessarabia — Krynychne (Bulgarian “Chushmeliy”). It was founded in 1813 by those Bulgarians who moved to the territories of modern Ukraine from northeastern Bulgaria, from the Shumen district. Until the 40’s of the twentieth century, the village was called Cheshma-Varuita (Romanian “Cișmeaua-Văruită”, meaning “stone-framed and whitewashed”), after which it was called Krynychne.

The village is located on the shore of the largest natural lake of Ukraine — Yalpuh. The waters of the lake saturate the soil and make it suitable for two main occupations of the locals: cultivation of arbazhek (onion-seedlings) and winemaking. Both of these wells are already being done not only domestically but also on an industrial level.

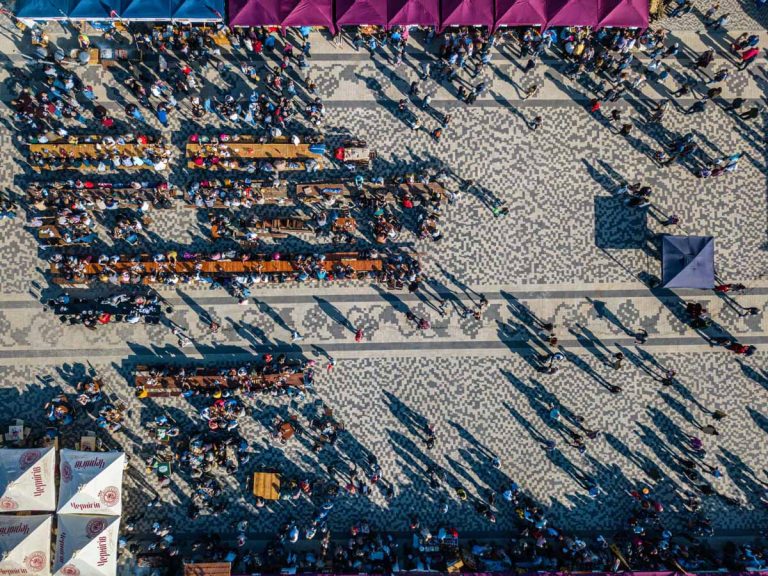

In Bolgard, the city founded by Bulgarian settlers in 1821, for the ninth year in a row, international wine and Bessarabian food festival, Bolgard Wine Fest, takes place, gathering the winemakers from all over Ukraine, as well as guests and participants from Bulgaria and Moldova.

Maria and Valerii. Wine and cuisine

Interestingly, the current sustainable association of Bessarabian Bulgarians with winemaking as their main occupation is a relatively new trend. Winemaking was not traditional for the Bulgarians of Ukraine as soon as they settled in Bessarabia. At that time, they were mainly engaged in animal husbandry, and later in agriculture. The tradition of making wine originated centuries ago, when generations became accustomed to new lands and were able to settle here.

In Krynychne, there are not only domestic wineries, but there are also large industrial ones. The Kolonist Winery, which produces wine for the Ukrainian market and for export, was founded in 2005 by Ivan Plachkov, the resident of Krynychne who has Burgarian origin, as well as many of his fellow winemakers.

Maria and Valerii Zheliaskovyare a couple of winemakers who have a home winery. They only started selling their wine recently, before experimenting with grape varieties and looking for the perfect production technology. They say they are still on the lookout. It is difficult to refrain from turning grape juice into wine. Mariia tells:

— There is wine in every yard: in different quantities, with different flavors. If you go into a house and there is no wine, it is not Bulgarian. A true Bulgarian should have good red – tart and tasty — wine.

The process of making wine, according to Zheliaskovy, is: first, a bunch of grapes on a special machine is separated from the branches. Failure to do so will cause the wine to have a bitter taste. Next, the grapes are ground in a wine press (gravy), mixed with other berries and poured into the liquid (kernel) in the barrel, where it ferments for three to four days. Before pouring the squeezed grape juice into the barrels, where it will ferment further, the couple gives it for examination: whether it is suitable for making wine.

After the wine is finally fermented, Maria and Valerii pour it into glass bottles. It is said to be the best storage vessel. After 40 days, it is necessary to pour it into a new container. Then it can be stored for several years.

Among the wines produced by Zheliaskovy, there are Saperavi, Cabernet, Odesa Black, Chardonnay, Aligote, and others. After Maria and Valerii first presented their wines at the Bolgrad Wine Fest, people started buying them regularly:

— At first, we treated the guests with wine. Here’s how we do: you came — well, have a bottle. The person liked it, and this is how out wine was accessed.

In Krynychne, it is a common thing: to come and have a glass of wine. It is said that it is more common to offer wine to a guest than coffee or tea. For every local family, the norm is to have at least half a hectare of vineyards. The grapes of Zheliaskovy grow on the banks of the estuary. Such location is very good, explains Maria:

— Grapes are always good, it ripes well, because it is near the water. If necessary, it is watered because sometimes there are droughts, as it was this year: then the grapes would not ripe and need extra attention.

Old photos hang in Maria and Valerii’s house: there is a story of sorts, Maria says:

— Old photos — in this house: my great-grandfather with the same barrel that serves us today – wooden one. They took a photo — they wanted to have a small business card and the first thing that came to mind was to write: “The wine they put their soul into”.

Bulgarians have traditional Bulgarian food served to the wine. Usually these dishes are served hot, because their main ingredients — brynza cheese, eggs and milk — are best tasted right from the oven. A popular type of pastry for local Bulgarians is the milina — roasted vertuta made from flour with added cheese, eggs and melted butter. In Krynychny, milina is also called “zelnik”.

The dough is thinly rolled and brynza cheese is spread on it. Then filling is added: milk and egg. It makes the pastries airy, says Maria. She convinces that baking is usually prepared as a snack for wine. Although they also eat milina with tea, with main dishes, and as a dessert.

After moving to Bessarabia, the Ukrainian Bulgarians were able to preserve the main feature of their national cuisine — the superiority of vegetables over other products. Here, for example, there are various variants of baking sweet — “Bulgarian” — pepper: stuffed with rice, meat and onions. This pepper is called “topkani”, and pepper fried with onions and eggplant — “ignia”.

The Bulgarians have partly adopted the traditional cuisine of the Crimean Tatars. Kubate, the meat pie, and chorba, the meat soup are often served on the table by Bulgarians. There are two other traditional Bulgarian dishes: kavarma and cabbage soup. They are usually placed on the wedding and commemorative table.

One of the most common dishes of Bessarabian Bulgarians is kurban. Lamb meat is a major component here. It is boiled, then taken out and added to the broth: porridge with rice in the proportion of two to one. Afterwards, they put the meat on the porridge and put it in the oven for about an hour.

It is important to keep the ratio of all products, because too thick or liquid kurban is wrong. The recipes are different in every Bulgarian village: someone does not add porridge, someone puts meat with lamb in the broth. Maria tells:

— In our village, it was preserved, we have not changed anything. If my grand grandmother cooked kurban this way, and my grandmother remembered it from her, and my mom did the same, then I would not cook the kurban differently.

Many traditions of the Ukrainian Bulgarians are unique. Bulgarian researchers cannot find similarities in their homeland or in Ukraine. Traditions are often different even in neighboring villages. Some are imposed on Ukrainian traditions (in particular, it is a calendar cycle), some are original:

— For example, Dmitri’s day is a day when shepherds release sheep, and on this day the peasants take their sheep home, that is, they no longer milk the sheep.

slideshow

On St. George’s Day, which is celebrated on May 6, the Bulgarians of Bessarabia, like Gagauz and Albanians, cut the lamb and cook kurban from this meat, having previously asked for a blessing from the priest, since the word “kurban” means “sacrifice.”

On the same day, Albanians celebrate the birthday of the national hero of Albania, Georg Skanderbeg, and the Gagauz — Heatherlez (nature’s Awakening holiday).

To ensure that every hostess of Krynychne does not heat the stove, the neighbors make arrangements. One housewife fires the over and everyone else comes to cook their own kurbans to her.

Bulgarians in Ukraine

The first Bulgarian settlers appeared on the territory of Ukraine at the end of XVIII — beginning of XIX century. Then the Orthodox Bulgarians, like the Albanians and Gagauzes, escaped the persecution of the Turks against the Christians, settled in southern Bessarabia, and established large settlements there centered in Bolgrad. Some of them settled in the Crimea (Tavria) and Prychornomoria, where they settled around Odesa and Mykolaiv.

The conditions for resettlement were favorable, since the emigrants then received incentives in the form of land, temporary military service and tax exemption, etc.

The next wave of resettlement started at the first half of the nineteenth century, when eastern Thracians (natives of southeastern Bulgaria) settled in the modern Prychornomoria, north of Odesa. After them, the Bulgarians from the districts of Sliven and Yambol came to the territory of modern Ukraine. Numerous waves of resettlement have led to the formation of a colorful culture of Ukrainian Bulgarians, which has survived to this day.

slideshow

In the second half of the nineteenth century, part of Budzhak (Bessarabia) was ruled by Romania, so the Bulgarians lost all the advantages and privileges granted to them by the Russian Empire. At that time, 30,000 Bulgarians from Bessarabia migrated to the Pryazovia region, where 38 settlements were founded. This is how the second large colony of Bulgarians in Ukraine, also known as Taurian Bulgarians, was formed.

In the village of Preslav (named after the Bulgarian city of Veliki Preslav) — the central settlement of the Azov Bulgarians near the town of Prymorsk — the settlers founded Bulgarian national districts where they successfully developed Bulgarian culture and published periodicals in the Bulgarian language. It lasted no more than a decade: in the 1930s, the Soviet authorities eliminated all their achievements, the same it did to other national communities. At that time about 25,000 representatives of the Bulgarian intellectuals were repressed and executed in the Pryazovia region: teachers, engineers, priests, agronomists, students.

In June 1940, Soviet troops entered Bessarabia. Soviet power replaced Romanian. South Bessarabia became part of the Soviet Union. At that time, the local Bulgarians lost some of their cultural identity, though they were recognized by the national community within the Soviet Union.

In 1944, within the framework of Stalin’s “cleansing” of the Crimea from representatives of other ethnic groups, 12.5 thousand Bulgarians were deported from the peninsula, together with the Crimean Tatars, Armenians, Greeks and Germans.

Part of the Bulgarian community died as a result of the 1946-47 Holodomor, which spread to both Budzhak and Prychornomoria region.

slideshow

Today, more than 200,000 Bulgarians live in Ukraine. They compactly reside mostly in Bessarabia and the Pryazovia. According to the 2001 census, Bulgarians are the second largest community in Bessarabia after the Ukrainians.

Along with the Bulgarians, there live Albanians, Romanians, Moldavians, Gagauzes, Ukrainians. The history, customs and way of life of these peoples are closely intertwined.

Customs and life

Immediately after moving to Bessarabia, the traditional Bulgarian house had the same appearance as at home in Bulgaria. It was an dugout or wicker house called a “bordei” or “burdei”. The whole family slept on the beat (putt guliam). On the walls were “charshafy” — silk carpets, and around the windows — silk towels, or “peshkiry”. The more carpets the owners had, the more affluent they were.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the Bulgarians adopted the tradition of whitewashing the houses with white clay or limestone. Inside, the building consisted of a shade and a living area: that is where the furnace body came out. Over time, the design of the building changed: a dressing room, gallery and kitchen were added.

In the center of the living room was an “oder” — a place to sleep. Previously, it was made of clay and then it was replaced with a wooden bed at the beginning of the last century. Nearby — a low table (“sufra”) and pencils.

Interestingly, a similar model of the house is preserved in the Bessarabian Gagauzes, which can be found more in our history: Gagauzes of Ukraine.

The Bulgarians of Ukraine, like other national communities, appreciate the land they live on because they have experience of resettlement. One of the sacred places for them is their own home. A home is a safe space.

They also honor their own traditions. There is a list of holidays when families must visit each other: Christmas, Easter, Trinity, St. George’s Day. They also celebrate the birth of a child, wedding and funeral.

The Bulgarian wedding traditions are quite similar to the Ukrainian ones. At first, the matchmakers negotiate with each other, then there is a tradition of a match (“the momari idut”, “svatyuil”) and betrothal (godezh, gudiesh, glavesh). The two main rites are kissing hands and exchanging gifts. The resident of Krynychny Tetiana Stanieva adds:

— We have a household tradition: when a daughter-in-law comes to her mother-in-law’s house, she must “dechie hatir nasikirvata”, that is, please the mother-in-law. This is something that everyone automatically understands: you are pleasing not the man, but the woman you called your mother.

All relatives and friends come to the wedding. As many people come to the funeral as they do to the wedding: first, to help them survive the day and bury the dead. The Bulgarians have preserved the crying during the funeral, also known in the Ukrainian tradition.

When a person dies, he or she goes into another world — unknown and incomprehensible. The relatives and friends are crying for the dead and asking him/her to return, because everyone who is not indifferent came to the funeral.

The Bulgarians also tend to throw coins and candy at the crossroads. You cannot touch them:

— And in fairy tales, if you notice, there are some great events happening at the crossroads. At the intersection, there are clusters of these otherworldly worlds, and when they throw away money, candy, it is possible (we do not state, but most likely), this is how they encourage the dead ancestors, in whom all the Slavs believed that they were helping.

slideshow

Maria Zhelyaskova tells about the rite of “arisvani”, or the rite of the god mother. Translated from the Bulgarian, “arisvan’” means sacrifice to the Lamb to God, and “arisvani” means one’s child to another woman or husband who has a wife.

Such a rite has Christian roots, but in Krynychne it acquired its peculiarities. It is possible to draw analogies with godparents, but in this case, the child may be baptized and god parents.

If the child is seriously ill or gets into a mess, the family decides to choose a god mother for him or her. This is a difficult decision, because in fact it is necessary to accept that the child, besides his or her mother, will call his mother another woman. Maria recalls:

— My son was ill, and I have made the decision: whoever enters our house tomorrow — let he or she become the second father or mother to my son and pray for him, wishing for a speedy recovery.

Maria’s sister was the first who came, and she became a boy called her mother. After that, says Maria, the boy began to recover. It happened on the eve of St. Dmitry’s day. It is on this day four years ago that Maria baked the Kurban and since then has been doing it every year:

— I made a promise to my son: while I’m alive, there will be a kurban on this table and there will be bread in the oven while my hands and legs are working, when I am able do it.

A child who has received a god mother also has a duty: to visit her on holidays. And for Easter he or she has to bring a cow (“korovaii”), prepared for loved ones, to the residence of the god mother.

The similarity of national communities and Ukrainians is evident not only in holidays and ceremonies, but also in material culture:

— There is a lot in common in the attitudes of Ukrainians and Bulgarians. In embroidery and even in colors: black and red are also typical colors for Bulgarians. And during the Holodomor, our grandparents went to Lviv to sell Bulgarian national outfits in order to get bread from there. This was in 1946, when, along with Soviet power, famine came to these lands.

Tetiana. Save your race

Tetiana Staneva was born and raised in Krynychne. In 2002, she left and moved abroad for a long time. But later she decided to return home.

It happened after one day when, in the center of Prague, Tetiana heard street musician playing Balkan music.

— How old have you been living here? Tetiana asked him.

“Over fifteen,” the man replied.

— Do you miss your home?

— I miss it very much. I had a life there, but had no money. I have money here, but I have no life. No money will replace my dear Balkans, friends and family.

slideshow

So Tetiana decided to return with her daughter to her native Krynychne. She noticed her desire to learn Bulgarian and therefore could not deprive the girl of this opportunity. More than 90 percent of the Bulgarians of Ukraine call the Bulgarian language their native language and speak it with each other.

Today in Ukraine, Bulgarian can be taught at the state level, at school. National communities have this opportunity, and Tetiana was among the first graduating students to study Bulgarian in elementary school. Now the Bulgarian language can be heard not only in everyday life:

— I am very glad that recently all public events are hosted in Bulgarian and Ukrainian. Just a couple of years ago, this was not the case.

Currently, Tetiana works for the NGO Bessarabia Development Center. The Center is engaged in cultural projects that are not only designed to revive the culture of national communities, but also to establish Ukraine’s contact with the world:

— Our slogan: “And Bessarabia will become the center of our revival.” We are sure that we already have what all nations are trying to achieve. We have a ready model of intercultural cooperation, and we can set an example for the entire Ukraine, Europe and for the whole world.

Naturally, when more than 200,000 Ukrainian Bulgarians speak Bulgarian in their everyday life, there are many local dialects. The Krynychne dialect belongs to the so-called Sіrtic Bulgarian dialects (by the name of the district of Srta in Bulgaria) and is quite exotic in the background of other sayings. Today, Tetiana speaks the way her grandparents used to speak. Such language, of course, is different from the modern Bulgarian literary language.

Today the village dialect is influenced by Russian, Ukrainian, Moldovian and Romanian. Tetiana recalls her friend, who speaks with her children not in Bulgarian, but in Russian:

— I say, “What are you doing?” She says, “To make it easier for them.” I say, “Do you realize you’re wrong? It will not be easier for them, they will grow up, believe me, and they will curse you for not teaching them their native language. ” This bilingualism (and in our case, trilingualism) is a gift.

Recently, Tetiana, together with a team of like-minded people, has made a documentary film “The Place of Power” about the Bulgarian Krynychne, where she has acted as a director and producer, as well as playing one of the main roles — a girl who wants to find her roots. The film is about those who are part of the history of the Ukrainian Bulgarians:

— When I started working on the film, I realized that I did not know anything about my village. I learned so much in the interview with the villagers, and it was a shame to cut it (the movie) then. I thought it should be a video chronicle for posterity and it is very important to save all the information, a word that conveys the history of each family and the history of the community.

slideshow

The first scene of the film is the cemetery where the Bulgarians are buried. At the cemetery there is a monument of the migrants with a poem by Bessarabian poet Niko Stoyanov. In the Ukrainian translation, it sounds like this: “They left the beautiful Balkans not to seek a better life, but to keep the Bulgarians alive and save their lineage.”

The movie “Place of Power” is an attempt to catch up with the tail of the past, which is being removed every year. Tetiana regrets that she did not have time to take Bulgarian folklore from her grandmother. So after her death, she decided to collect it by herself.

— Only when Ukraine became independent did such a revival begin, borders were opened, information became available, songs, we began to search for places where we belong. It enriches both ourselves and the national map of Ukraine in general.

— We are forever in a heart with two roots. Tear off one thing or another – and we will not survive. We cannot be without one thing. I personally feel that my heart, if you split it, that one half belongs to Ukraine and the other to Bulgarian culture.

The way modern Bulgarians appreciate Bulgarian and Ukrainian culture at the same time is an answer to the question of how one can live at the intersection of two vivid cultures and save their authenticity. It is possible.