Russians systematically violate the laws of war. One of the examples of such a violation is the expulsion of Ukrainians from temporarily occupied territories. Russia shells official humanitarian corridors, prevents evacuation of the population to the regions controlled by Ukraine, seizes passports of Ukrainians who were deported to the Russian territory, and limits their freedom of movement.

The Ukrainian delegation to the UN specifies in its statement that abduction and deportation of Ukrainian citizens is Russia’s crime aimed at destruction of the Ukrainian nation. It is a modern case of colonialism. Unfortunately, this is not the first time something like that has happened in the history of the Ukrainian-Russian relationship.

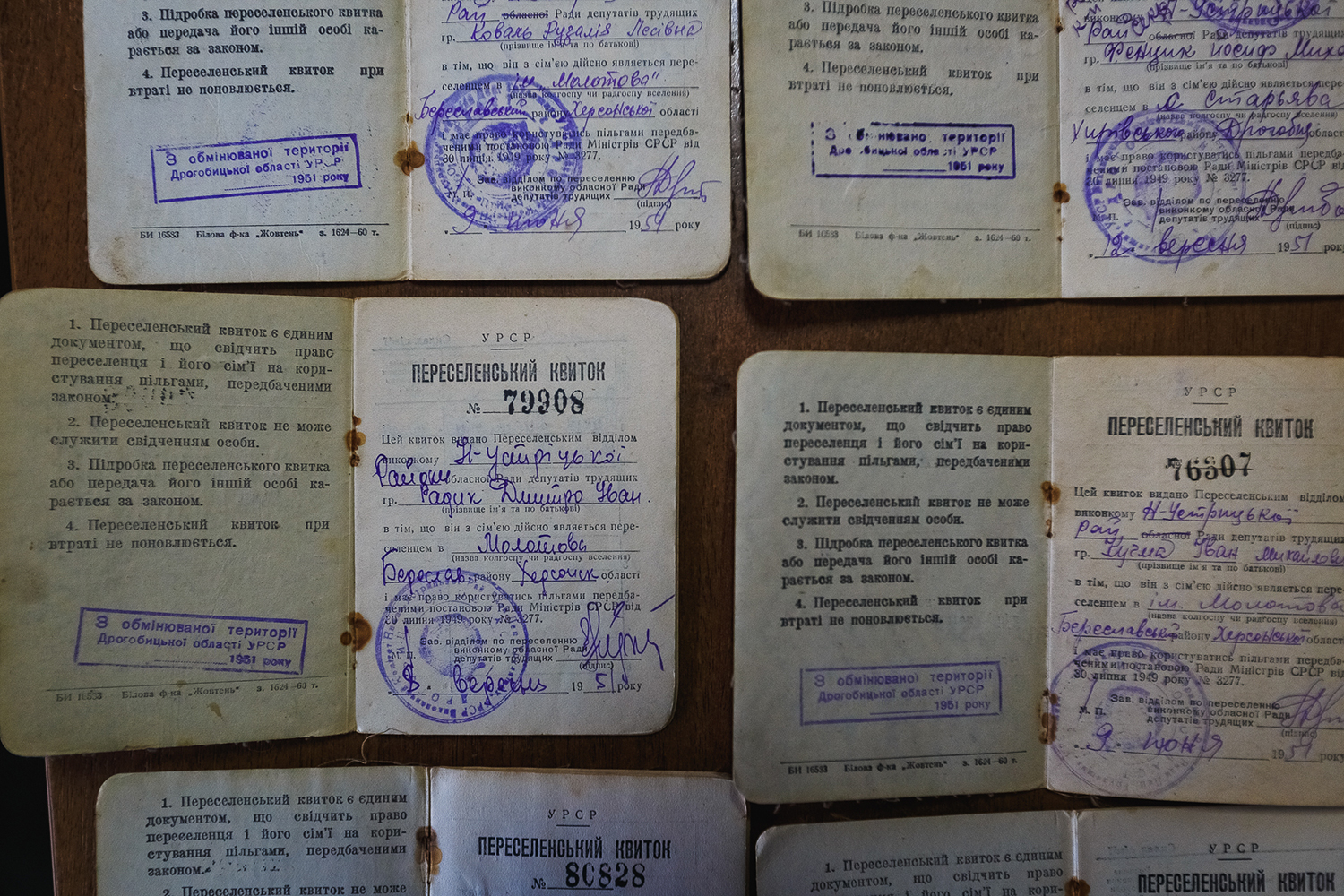

In the 20th century alone, indigenous peoples of Ukraine experienced several deportations caused by Russia. For instance, in 1944–1952, the Soviet Union authorities forcibly removed 700,000 people from Western Ukraine. They were later recorded as “migrants” in official documents. One of the reasons for deportation was clearing the region from “Banderites”, i.e. the families of members of the OUN (Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists) and UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army), who were considered “unreliable”. The Ukrainian Institute of the National Memory points out that this deportation caused “the destruction of the historical, material, moral and cultural values of Lemkivshchyna, Western Boikivshchyna, Nadsiannia, Kholmshchyna, and Pidliashshia, and put entire ethnic groups of Ukrainian people at risk of extinction.” The goal of the Crimean Tatars deportation in 1944 was similar — destruction of the identity of the entire nation that destroys the idea of “Russian Crimea since time immemorial” by its very existence.

Russia uses similar methods to this day, in the 21st century, continuing to look for “unreliable ones”. And even though these days Russia does not seem to deport Ukrainians for forced labour (as, for example, Nazi Germany deported Ostarbeiters during World War II), it puts many Ukrainian citizens in conditions just as difficult. This is manifested by the facts that Russians are seizing Ukrainian passports, and Russians are banning Ukrainians from leaving the remote Russian regions where those citizens have “agreed” to be legally employed, thus robbing them of any chances to leave Russia.

What takes place these days?

It is hard to tell the exact number of residents of Ukraine who were deported during the full-scale Russian invasion, not to mention the non-transparency of the process, as well as the fact that Russia deliberately inflates the data. As of mid-June, according to the official information of the Ukrainian government 1.2 to 1.5 million Ukrainians were deported, about 300,000 children among them. People are often removed to remote regions of Russia and are provided with documents prohibiting them from leaving the territory of the aggressor country for the next two years.

Russia itself, while having a habit of manipulating concepts and thus masking reality, calls its own actions “evacuation without the involvement of Ukraine”. In June Mikhail Mizintsev, the head of the Russian National Defence Control Centre, announced the deportation of approximately 1,8 million Ukrainians to Russia.

Russia opens up parallel corridors alongside the official evacuation routes organised by Ukraine. People in the territories temporarily occupied by Russians or in the combat zone often do not have mobile signal or Internet connection. Therefore they don’t always understand who exactly is carrying out the evacuation and where the facilitators are from, so they can get on Russian buses by mistake. According to some eyewitnesses, even as people realise that these buses will take them to the territory of the aggressor country, and try to oppose this, they are forced to board those buses at gunpoint.

Russia deports people from the occupied territories in the east and south of Ukraine to the so-called LPR/DPR or Crimea first, and then from there to Russia. All those who have been “evacuated” by the occupiers (men, women, children, the elderly) are forced to go through the filtration camps. These are the places where people are detained, interrogated, and body-searched. Their personal data is collected, and some forms are issued — for example, a certificate provided by the DPR (the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic) Foreign Ministry. Some people are forced to accept the “citizenship” of LPR (the so-called Luhansk People’s Republic). The occupiers are also trying to find information about the participants of Anti-Terrorist or Joint Forces Operations and their associates. Occupiers are also looking for information about connections to Ukrainian defense, law enforcement agencies, journalism or public activism. They look for any patriotic tattoos, and so on. In most cases it is precisely because of any manifestation of their civic position that people may not pass the filtration (and become detained — ed.).

The latest official information пabout the number of people detained in such camps was provided by Sergiy Kyslytsya, the Permanent Representative of Ukraine to the UN, back on April 20. According to him, at least 20,000 Ukrainians are being held in filtration camps on the Manhush—Nikolske—Yalta line (in the vicinity of Mariupol), and about 5-7 thousand in Bezimenne, Donetsk Oblast. From there Ukrainian citizens are taken by bus to the Rostov Oblast in Russia, and then to the places of temporary stay — special camps, dormitories etc. — all over Russia. Once there they are obliged to receive a Russian passport and get a job through employment centres. Afterwards they receive a document which imposes a ban on leaving Russia for two years.

According to former ombudsman Lyudmyla Denysova, Russia has been preparing for the mass deportation of Ukrainians since the beginning of 2022. The Kremlin was sending the guidelines with information on how many camps for deportees were needed and how many people they were supposed to accommodate, to the regions where Ukrainians are now being taken. Likewise, even before the full-scale invasion, Russian authorities prepared case records for illegal adoption of Ukrainian children deported from the occupied parts of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts since 2014. In June the invaders announced the issuing of Russian passports in the temporarily occupied territories of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia Oblasts. And in the Kyiv Oblast the Security Service of Ukraine has discovered passports of the USSR — Russian authorities were planning to issue those to the locals in the case of full occupation of the Oblast, at least until the Russian official documents could be issued. This is another way to put people on record and impose the “Russian world” in the temporarily occupied territories within the shortest period of time possible.

Denysova also reportsthat people who do not pass the filtering are treated by Russians as “dangerous to the Russian regime”. Consequently, they get arrested and taken to the former correctional facility № 52 in the Village of Olenivka in Donetsk Oblast, or to the “Isolation (Izolyatsiya)” prison in Donetsk (the prison on the territory of the art centre occupied by thuggish militia in 2014 — ed.). There the deportees fall victims to physical abuse and threats, they are forced to collaborate, and the “unreliable” ones are tortured.

Where are the people being taken to?

In March 2022 during the temporary occupation of part of the Kyiv Oblast the Russian military would not allow the local people to leave for the Kyiv direction. Instead of that they arranged their own corridor for civilian cars and buses to the territory of Belarus, which is Russia’s accomplice in this war. Some people found out what their destination was only inside those vehicles they had been brought into. According to eyewitnesses, people were brought to the city of Mozyr in Gomel Oblast of Belarus, and accomodated in a dormitory. Many of them did not even have a chance to take their documents, thus the Consulate of Ukraine in Belarus issued documents confirming their identity.

According to Mustafa Dzhemilev, the leader of the Crimean Tatar people, the kidnapped activists from the occupied Kherson and Zaporizhzhia Oblasts are being taken to Crimea. They are kept under arrest for some time, and then are sent deep into Russia. Sometimes they get rescued owing to the corruption in the Russian security forces – Ukrainian citizens are literally “ransomed” for $250 or more. However, this is not always possible. There have already been cases of people gone missing.

People from the east of Ukraine are mostly taken to the border areas of Russia first, and from there to more distant, economically depressed regions. There are 4 camps in the Penza Oblast alone, where deported Ukrainians were moved back in February, before the full-scale invasion. There are known cases of deportation to various regions: to Siberia, beyond the Arctic Circle, to Chechnya, Dagestan and Ingushetia, to the Far East. This was reported in April by the British media – The Independent, which was referring to documents from the Kremlin. The Russian Orthodox Church takes part in this process as well. They settle the deported people in their churches and monasteries.

In March it was also reported that the International Red Cross Society (IRCS) facilitates the deportation of Ukrainians (unlike the Ukrainian Red Cross division, which helps people in the occupied territories). On its web page, the IRCS published a report on 61,000 “evacuated” residents of the so-called LPR/DPR as of February 21, i.e. prior to the full-scale invasion. People were mostly taken to the Rostov Oblast. This raised significant public concerns, and the report was deleted soon after. However, the question of precisely how many people were deported remains unanswered. That’s why Ukrainian authorities requested the IRCS to demand the list of all deported Ukrainian citizens from Russia.

Why do these actions of Russia qualify as war crimes?

Russian authorities are trying to present their actions as aid to Ukrainian refugees, who are fleeing the shellings arranged by the so-called “Nazi regime”. The truth is that all this contradicts international humanitarian law and is considered a crime. This, among other things, is indicated in Article 49 of the Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War of August 12, 1949 and in Article 85 of the Additional Protocol (I) to the Geneva Conventions. Both documents prohibit forced displacement of civilians from the occupied territory to the territory of the occupying state. Any state has to adhere to these norms, irrespective of whether it has ratified the Geneva Conventions or not.

Citizens of Ukraine must be evacuated to the territory of Ukraine in accordance with the principles of international law. Evacuation to the territory of the aggressor country is possible only if their own state does not agree to accept non-combatants (which is not the case, given the fact that Ukraine is keen to return its citizens to its government-controlled territories).

Russia has to cease fire while the “green corridors” are in operation, facilitate their functioning, and cooperate with international organisations which protect civilians. In reality the military of the occupying country not only deport civilian people, but also create conditions which force the citizens of Ukraine in the temporarily occupied territories to use the evacuation routes through Russia and no other.

Among other principles of international law violated by Russia, there is Article 7 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. It defines deportation or forcible transfer of population as a crime against humanity. And Article 8 of the same Statute qualifies such actions as a war crime.

Given that Russia also unlawfully detains Ukrainian citizens in filtration camps, it violates Article 9 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Both documents declare people’s right to liberty and security, and prohibit unlawful arrest or detention in contravention of the provisions.

What is known about the deportees?

Since the end of March the occupying country reassures that it pays out one-time financial aid to all “refugees” in the amount of RUB 10,000 (the equivalent of $165.91 USD — ed.), and provides them with food and jobs. However, even Russian sources report that people have not been receiving these monies for months.

Russian society helps Ukrainians deported to Russia in different ways – more often than not referring to those people as “refugees”. For instance, Dmitriy Muratov, Russian journalist and TV presenter, has sold his Nobel Prize medal received in 2021. He promised to donate the proceeds to UNICEF as humanitarian aid to Ukrainian children displaced by the war. In his speech he named Russia as one of the countries that hosts homeless Ukrainians.

One of the activists posted on her Instagram page a giving campaign to raise money for a program that helps the deported children adapt psychologically to the Russian environment. At the same time, she emphasises that many of the deported Ukrainians “have willingly chosen to go to Russia”.

Some Russian volunteers work directly on the Russian border. One of them, Oleg Podgornyy, reassures that they strive to help people, to save them from the horrors of war. At the same time, he does not recognise Russia’s aggression and insists that the “refugees” themselves do not blame the aggressor country.

There were cases when deported Ukrainians became the subject of Russian propaganda. At Russian railway stations they were met by local law enforcement officers, journalists and volunteers who were supposedly helping the “refugees” while filming that on cameras for TV.

Russia is acting quite hastily in the legislative field as well: on May 13 the Federation Council stated at its session that not all children from the so-called “liberated territories” speak Russian at a “sufficient” level for studying in schools, therefore it is planned to create a specialised language courses for them in the summer.

In Russia, they are also “tackling” the issue of Ukrainian orphans. In May, Russia’s President signed a decree according to which orphans from the temporarily occupied regions of Ukraine (Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia Oblasts) can obtain Russian citizenship through a simplified procedure.

What is actually happening to the deported Ukrainians, in what conditions they are being held, whether anyone really helps them — it is difficult to see a complete picture at the moment. Official Russian information often differs from reality. For example, Ukrainians whose children were born in deportation cannot take them out of Russia because of a Russian birth certificate. There were cases when people were kidnapped and “deported” straight to prisons in Russia, as happened to the Ukrainian Red Cross volunteer Volodymyr Khropun.

In many cases Ukrainians also face severe climatic conditions. Petro Andriushchenko, the aide to the mayor of Mariupol stated that a part of the deported Mariupol residents were sent as far as the Sea of Japan coast in Russia, where the winds are constantly blowing, and the warmest month is August with temperatures of +21ºC. Furthermore, Ukrainians are refused the necessities. They are kept in a dormitory, without any means or opportunity to contact anyone, instead they are offered low-paying jobs.

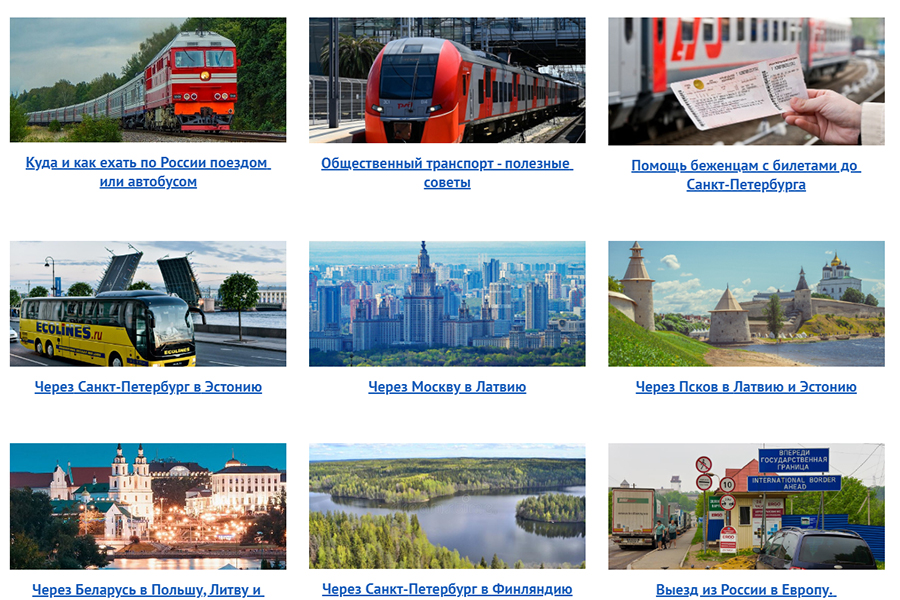

Ukrainians are trying to escape from Russia as soon as possible, to get back to the territories controlled by Ukraine, or at least to some other countries. Some of them succeed, but this is not easy in any way. For instance, as of mid-May, the office of the former Ukrainian ombudsman together with Russian volunteers helped about 50 Ukrainians leave. Other deportees are looking for escape routes on their own, armed only with knowledge.

What can deportees and their families do?

Ukrainans who ended up in Russian territory are advised that they are not obliged to register for migration or agree to stay in the camps for deportees. The Ukrainian government is creating a procedure whereby border guards will be able to admit Ukrainians deported to Russia, even without documents. Iryna Vereshchuk, Minister for Reintegration of the Temporarily Occupied Territories, emphasises that the most important thing for such people is to find a way to reach the border with Ukraine.

For those who could not avoid being registered as migrants or getting into camps for deportees, the main recommendation is not to agree on getting a Russian passport. This will make travelling to third-party countries much more difficult. Owing to the recent years’ initiatives to digitalise governmental services, Ukrainians can use the official Diya application on their smartphones to access their ID details. They are strongly advised to do their best to leave for third countries as soon as possible. To help people leave various organisations such as I Support Ukraine, BYSOL, UA-RU-EU, Ukrainian Helsinki Human RIghts Union and others create guidelines, chatbots and instructions.

Both the Ukrainian government and volunteers are doing their best to support Ukrainian citizens who have been deported and bring them to safety.

To those who were deported the following recommendations are offered

1. Delete from their phones all the information that may seem suspicious to the occupants. This could be discussions of political issues, condemnation of Russian aggression or Putin’s policies, photos of military equipment or of the damage it caused. There is a comprehensive guidebook on how to do this in Ukrainian.

2. Write down, save and hide the contacts of relatives, friends or loved ones in a safe place, in case the phone will be taken away.

3. Protect social media accounts and messengers: set up two-factor authentication, make the profile private, delete conversations that may seem suspicious.

4. In the likely event of interrogation in the filtration camp, people are advised to keep calm, provide neutral answers, do not argue or discuss political issues, and do not respond to provocations.

5. Whenever possible, do not give a passport or other personal documents for stamping. People are also recommended to keep both paper copies and digital versions of all of their documents.

6. At the first opportunity, people should inform their relatives inside Ukraine who can contact the relevant state authorities about their location. If possible, they should also provide their information to the nearest embassy of Ukraine abroad in neighbouring countries or possible transit countries.

7. Given the chance, people should go to neighbouring countries. Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania accept all Ukrainians with any identity documents: a Ukrainian passport (including the old-style ones), an international passport (including non-biometric ones), or even with an expired passport.

As for those who come to know about cases of deportation, the Ukrainian authorities ask them to do the following:

1. To notify the relevant government authorities:

by reporting a crime with the police, the prosecutor’s office, or the Security Service of Ukraine

by sending an email to the Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights at hotline@ombudsman.gov.ua or call the Hotline 0 800 50 17 20

– by filling out the notification form on the website warcrimes.gov.ua (it was created by the Prosecutor General’s Office for documenting war crimes).

2. To email directly the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court that collects evidence of war crimes committed in Ukraine at otp.informationdesk@icc-cpi.int.

3. To contact the association of human rights organisations “Ukraine. Five in the morning” (warcrimesos.ua@gmail.com) that collects and documents war crimes committed by Russia during the war in Ukraine, and provides legal aid.

4. Where possible, people are requested to provide detailed information of:

– where the deportation has occurred from

– places where the filtration camps were located

– where exactly the person was sent to after the “examination”

– data on occupiers involved in forced displacement (government authority, rank, personal data or callsigns)

Every day the Ukrainian authorities, NGOs and activists attempt to help and return the deported Ukrainians home. They call for everyone to make this war crime public by spreading the word about it and reaching out to international organisations.