The full-scale war against Russia was expected. Still, on the 24th of February, it caught a lot of people by surprise. Insidiously advancing from the territory of Belarus, the invaders quickly made their way from the north. They temporarily occupied part of Kyiv Polissia, Sivershchyna, and Northern Slobozhanshchyna.

Thanks to the Armed Forces of Ukraine and brave local guerrillas, on the cusp of March and April, the occupiers made a “gesture of goodwill” and left these territories. Reconstruction of the regions has begun: demining, demolition of rubble, delivery of humanitarian aid to affected locals, etc. Journalists, documentarians, and photographers also had the opportunity to visit the de-occupied settlements to record the crimes of the Russian army and the eyewitnesses’ testimonies and comprehend the new reality.

Photographer Yelyzaveta Bukreyeva

Yelyzaveta Bukreyeva is a Kyiv-based photographer who has been creating the Scars of a Lost Humanity project since April 2022. This is a photo series about living in the liberated cities in the north of Ukraine. The author says her photos are about changes in the people’s faces, landscapes, and things they are used to:

“It’s a juxtaposition: everything is blooming, and people are coming back, whereas ‘scars’ in the city, like a projectile stuck in a tree, remain.”

We are introducing you to the photos of Yelyzaveta Bukreyeva, taken since the beginning of the invasion, and her reflections on the war, photography, and people.

Photography is my life, I treat it like a language. A photo tells a story not only visually, but also at the level of feelings, because people look at the details and are filled with emotions. I am an introvert, so I can be better understood through the language of photography.

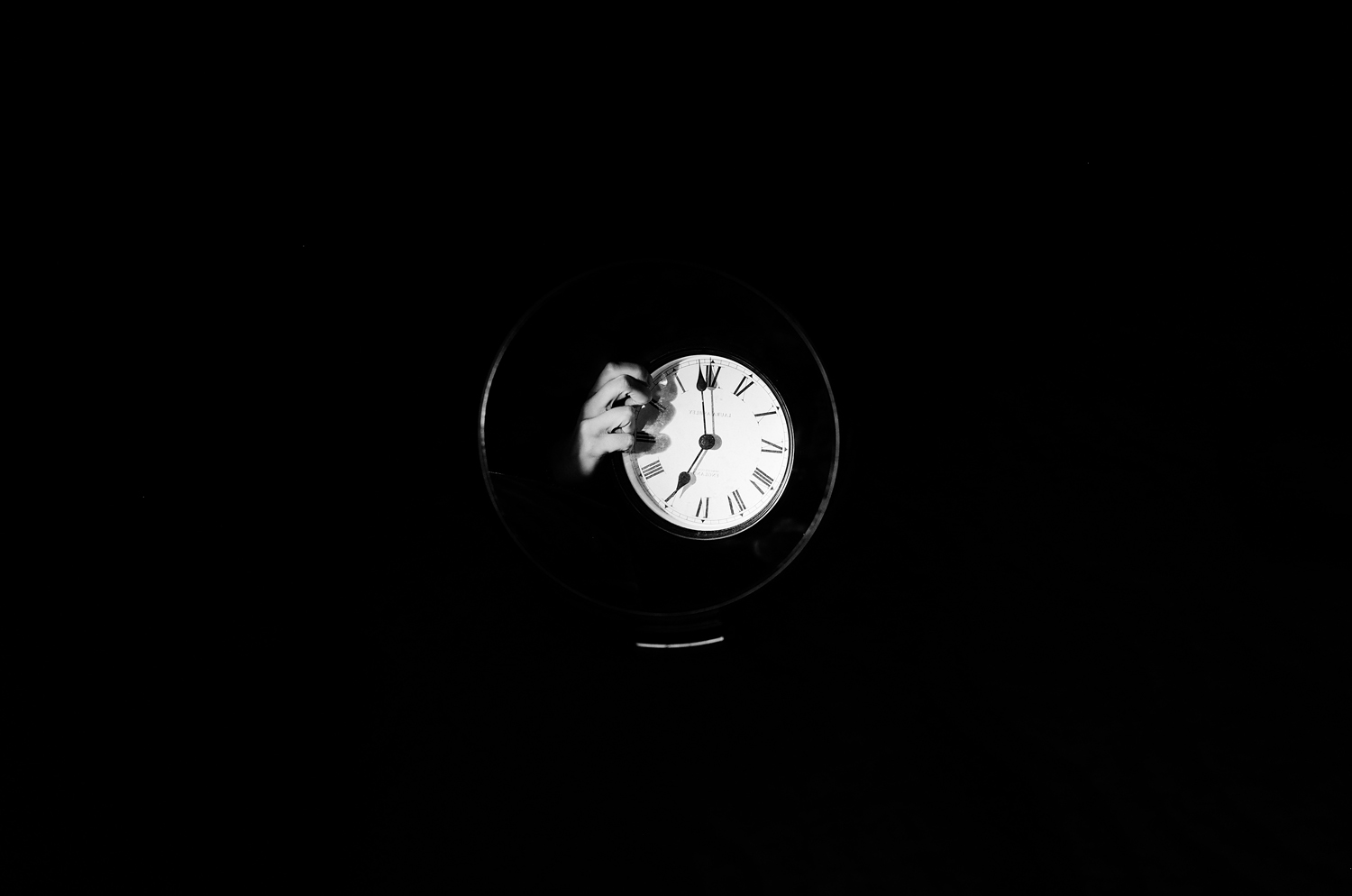

5 a.m. on February 24, when Yelyzaveta’s family woke up because of explosions sounds

It’s hard for me to go back to pictures. I recently found my war diary — these are photos from the first month (invasion. — ed.). I added this series to the site and selected photos for the exhibition. They are difficult to review, although I do not have such a traumatic experience of war. I have everyone alive, no one was hurt, they were in Kyiv. But I remember myself at that moment, all those experiences, my younger brother, who was very afraid and worried in the first weeks. Now we are adjusting to the new reality, and then there was only confusion. Everything you knew and prepared for went wrong.

Yelyzaveta’s selfie, the first time she returned home since full-scale war broke out.

Yelyzaveta’s brother sleeps on the floor on the first night of the Russian invasion.

At the beginning of a full-scale invasion, people were afraid that too many photos could cause a missile strike. They used to argue with me all the time. It was necessary to explain to people what I was filming, why I was doing it, and that I did not want to cause them any harm. It seems to me that photographers should do this to change attitudes.

Reasons of missile strikes

It is known that the occupiers took most of the information to adjust the shelling from open sources, so the local authorities and the military strongly urged civilians not to publish photos and videos from the sites of the hits earlier than official sources.

Children's playground in Bucha.

An artillery shell got stuck in a tree. Kyiv Polissia.

“In one city, a woman asked me: “What are you filming there, our suffering?”. Then I explained that the war is not over yet, winter is coming soon, and they have no flats. If it is documented, then other people can see, react, and help. She immediately became gentler: “Sit down, kiddo.” It is essential to explain. It is worth talking about.”

“I film a lot on the streets, and now people are treating photographers better because they understand that we have an impact and can bring attention to their community.”

Olena brings new windows to her partially destroyed house.

“I think the role of a photographer during a war is crucial. If you have something to say, do it, even if you are not a professional. Document it when you have something to film. Whether it’s the aftermath of strikes or war crimes, everything matters. Thanks to photography, a huge number of occupiers’ crimes can be proven.”

Pulitzer Prize

A prestigious American award in the field of literature, journalism, music and theater, founded by publisher Joseph Pulitzer. Awarded annually since 1917.A huge number of crimes of the occupiers can be proved thanks to photography. When the Russians accused us saying that Bucha was staged, satellite images quickly proved the authenticity of the pictures from there. No matter how much money the Russian government invests in promoting its messages, no matter how much it shouts that it is fake, no propaganda can erase or slander the truth. The juxtaposition of ordinary photos and satellite images, which cannot be faked, works flawlessly for the world, with such evidence it is no longer possible to distort reality.

Bucha

A town near Kyiv, the occupation of which became one of the symbols of the invaders' war crimes against the civilian population. The first mass burials of Ukrainians who had previously been tortured were discovered here.One time I was testing the flash while I was setting up the camera and it worked. One boy became very scared. He was standing quite far away, but the flickering was powerful. She apologized, said it was just a photo. It was an awkward situation, poor boy. Children have a bad reaction to the camera flash, so I don’t even ask them, I just don’t shoot with the flash. And I ask adults, they usually agree. They say that they are no longer afraid of anything.

Valentyna. Russians kept her and about 300 other residents of the village for almost a month in a small basement. Many slept standing, leaning against the wall.

Artem and Fadei in the ruined church. Lukashivka, Sivershchyna.

A boy waves the Ukrainian flag at a roadblock organized by children. They stop cars, ask "quiz" questions and give candy. Sloboda, Sivershchyna.

“Now everyone looks for photos of the front from the east and south because it attracts more attention, and here (in the liberated territories of Sivershchyna and Polissia. — ed.), few people film. Nevertheless, people still live with the consequences of the occupation. They all as one say that they are most afraid of a repeated invasion from the territory of Belarus, they follow the news…”. Photographers who traveled to Kharkiv and the south of the country say that visually destroyed cities look the same everywhere. I don’t really agree with this, because it seems to me that behind every destruction there is a separate human story. They cannot be equated.

Bohdan, a resident of Bucha.

In the “Scars of a Lost Humanity” series, I am most impressed by the portraits. When you get to the liberated cities, you feel the stench of war: this manure, melted metal, dust, sand… But the people there are very friendly, everyone welcomes you. They want to talk about anything: where we are from, how we are, what we experienced, how much does the milk cost in Kyiv. I saw these people more than once, we came and found out who needs feed for the animal, who needs buckets, who needs an ax. So all the portraits definitely remained in the memory.

Natalya was born in Belarus, but she bought a house in Ukraine. She survived the Russian occupation.

Svetlana near her apartment building. Her apartment is on the fifth floor where a Russian missile hit. Horenka, Polissia.

Dmytro, Borodianka, Kyiv Polissia.

“Destroyed high-rise buildings are visually striking. I probably remember each one of them. They usually look as if they were cut. You can see what kind of flats there were and how people used to live there. Once in Borodianka, I met a woman who stayed alone in a house that had an entire section of the building missing. She went outside to shake out the carpet and said: “I cleaned it two days ago, and it’s dusty again. It needs to be cleaned [again — ed.]…”. There are no windows, water supply, or gas. There is nothing… And she is worried about the carpet.”

Destroyed house in Borodianka, Kyiv Polissia.

A rug with the words "Welcome Home" next to a completely destroyed high-rise building. Borodianka, Kyiv Polissia.

A ruined house with cabinets that survived. Horenka, Kyiv Polissia.

A high-rise building burned down in Irpin, Kyiv Polissia.

Pretty quickly, I realized that we couldn’t comprehend and experience all this horror. I mean, the psyche protects us: we see everything, understand it, know it, but we don’t fully realize the tragedy. Because we simply can’t exist with it. It freed me up as a photographer. I understand that no matter what I know, no matter what I show, no matter what video, no matter what book I make, it won’t be enough.