Today, the world is witnessing the inhumane atrocities committed by an empire that has spent centuries creating a powerful propaganda machine. Russia’s historical and cultural development is an integral part of its imperial policy, which cannot refrain from encroaching on the historical heritage of other nations. Russian inroads on the achievements of others induced virtually all areas of life: the history of statehood and national symbols; world-famous writers and artists; inventions, technology, and goods; and national cuisines.

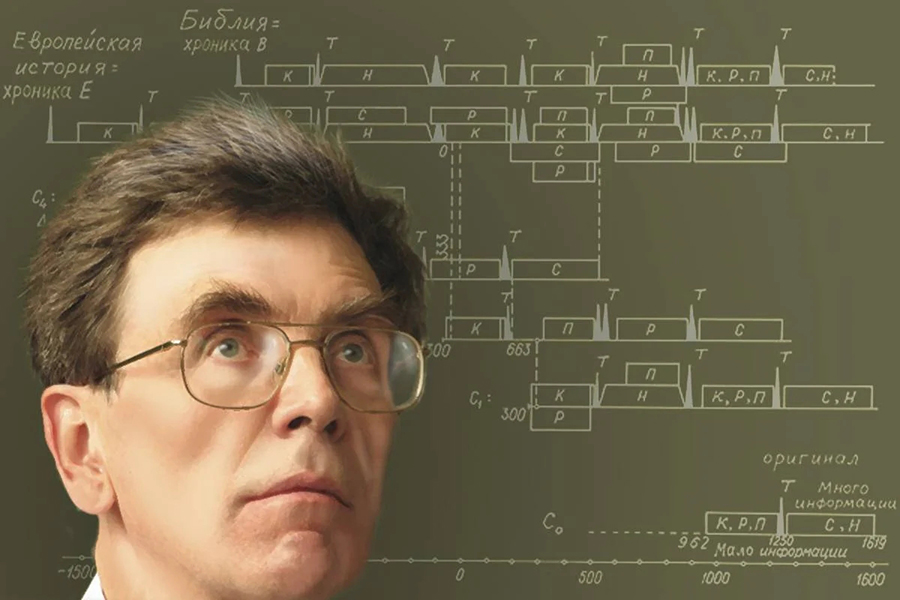

Sometimes these infringements reach complete absurdity. For instance, a Russian Academy of Sciences member, Anatoly Fomenko, has developed the so-called “New Chronology”. It is a pseudo-scientific concept, claiming that history begins in the tenth century and all ancient civilizations are fictional. According to Fomenko and his followers, the Amazons lived on the territory of present-day Russia, Genghis Khan was of Russian descent, the Russians built ancient Egyptian pyramids, and even the discovery of America was the merit of immigrants from Russia.

Volodymyr Seleznov thoroughly explains Russia’s appropriation of other states’ cultural, historical, and economic achievements in his book “Kremlin’s Plagiarism: From Monomakh’s to Lenin’s Cap.” The publicist explains the reason behind the empire’s attempts to appropriate the heritage of Ukraine and other nations: Russia’s desire to reestablish hegemony over the former colonies and satisfy imperial whims. Another telling detail in colonialism theory is the metropolis’ exploitation based on the “what is yours is ours” principle. That is how Russia has been attempting to regain its former power for many years.

Encroachment on History

One of the Russian propaganda’s favorite narratives, popular back in the USSR and backed by Putin’s pseudo-scientific rhetoric, is the common origin of the “three fraternal peoples” – Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Russians.

Russia considers itself the successor of Kyivan Rus, appropriating its cultural, socio-political, and historical achievements. In fact, Russia’s history is only partially related to Rus: when Kyivan Rus was rapidly integrating into European space, Moscow was merely an appanage principality in it. The historical destiny of Russia as a state formation began during the reign of Yuri Dolgorukiy, the son of Kniaz (Prince) Volodymyr Monomakh of Kyiv. In the middle of the 10th century, he began to rule in Zalissia — the land where Moscow later appeared. According to the historian Andrii Pavliashyk, the “discord” between nations occurred when Dolgorukiy’s son, Andrey Bogolyubsky, burned and plundered Kyiv.

— The Kyiv pogrom demonstrated the disintegration of a once-unified state and population. Zalissian (Russian) troops destroyed the city the same way they destroyed the foreign ones. Kyiv was as foreign to them as any German or Polish castle.

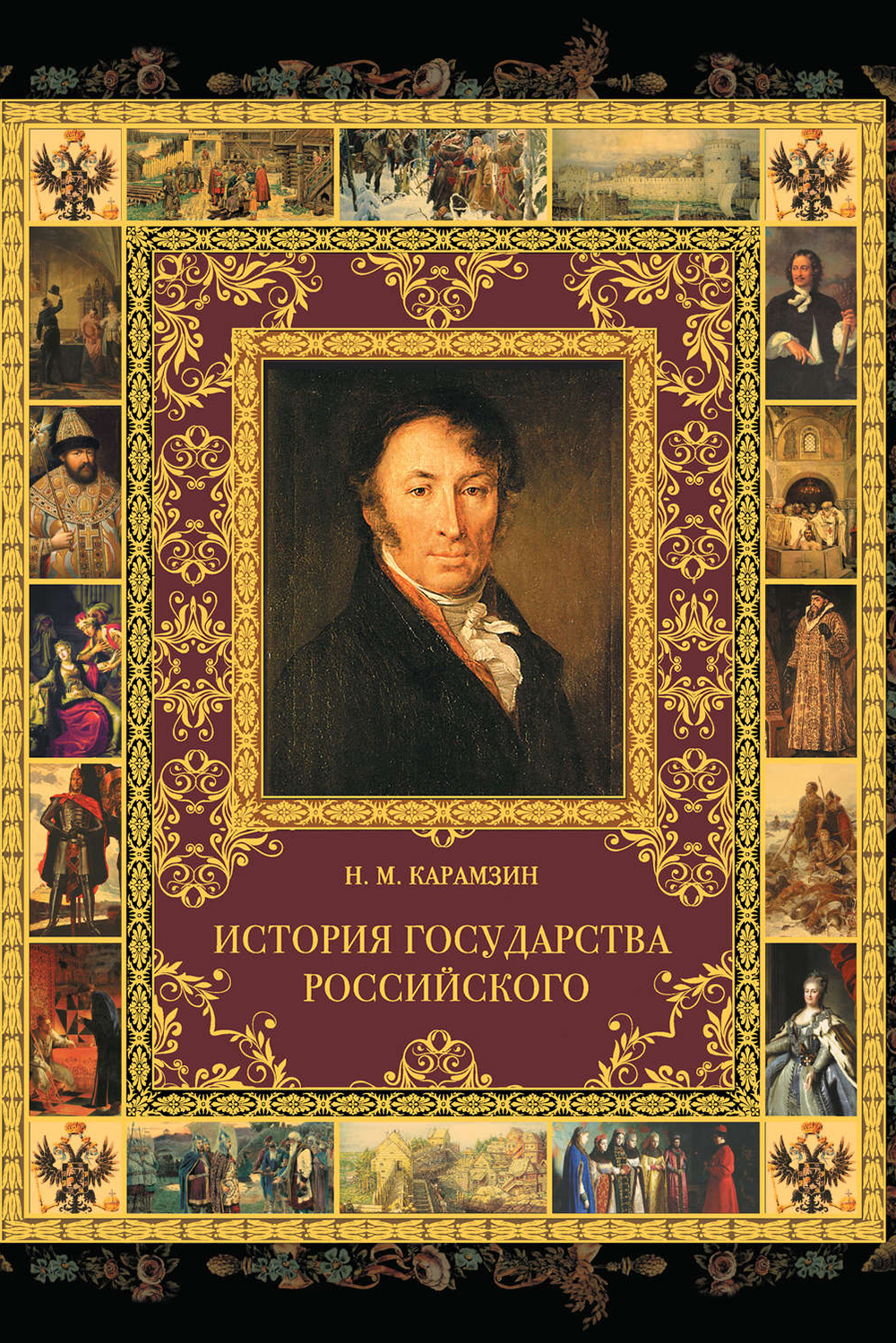

The Russian Orthodox Church started picturing Bogolyubsky on icons in the 18th century as a sign of worship. Russia began systematically rewriting history even earlier, but the practice reached its apogee during the reign of Catherine II. The Empress was concerned about the Muscovy’s cultural and historical poverty, so she decided to organize a special commission to create a new history of the state. Subsequently, somefalsified “historical sources” appeared. The most notable of them were the “History of the Russian State” by Nikolay Karamzin and “History of Russia from Ancient Times” by Sergey Solovyov. As a result, the Russian Empire appropriated Kyivan Rus’ cultural heritage. The “one nation” myth originated directly from these works.

Even after several hundred years of legitimizing stolen history, the antiquity of Kyiv stood out like a sore thumb for Moscow. The Kremlin dismissed and diminished Ukrainian history during the Soviet period. During WWII, the Soviet military planted explosives in monuments and shrines associated with the historical development of Ukraine. Miraculously, Saint Sophia Cathedral was saved: before retreating from Kyiv, one of the Red Army soldiers was supposed to blow up the building. The head of the Museum of Saint Sophia Cathedral managed to stop the soldier; the Bolsheviks made a similar attempt to destroy the monument in the 1930s. The St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Cathedral, built in 1108–1113 by Prince Sviatopolk Iziaslavych, could not be saved. In August 1937, the monastery was destroyed by order of the Soviet authorities. It was later rebuilt in 1997–1998.

For Moscow, Ukrainian history is still a sore topic. Russian troops threatened the Sophia of Kyiv once again during the full-scale invasion while also methodically destroying Ukrainian cultural and historical centres. The Map of Cultural Losses documents dozens of Russian crimes, including the bombing and shelling of Mariupol’s Drama Theatre and Kuindzhi Art Museum, the Hryhorii Skovoroda National Museum in Slobozhanshchyna, and the Ivankiv Museum, which housed Maria Prymachenko’s works.

In addition to historical thefts, the ancestors of today’s Russians also succeeded in religiousones. For centuries, Russia has positioned itself as a “majestic Orthodox state.” Still, a different, more telling story is associated with the establishment of the Moscow Patriarchate. In the 16th century, the Regent of Russian Tsar Boris Godunov tried to persuade Patriarch Jeremias II of Constantinople to recognize the autocephaly of the Moscow Church. When Jeremias II refused, Russians took the matter extremely serious and forced him to sign. The Council of Constantinople recognized the Moscow Patriarchate in 1593.

State Symbols

State symbols represent the nation’s interests, embodying its views on state policy.

Despite long-standing imperialist tendencies and territorial expansions, the creation and establishment of state symbols in Russia has been slow and rooted in foreign soil.

In his aforementioned book on Russian appropriation, Volodymyr Seleznov says that there was no officially approved state coat of arms in Russia until the 16th century, but heraldic seals serving instead. In comparison, Riurykovyches has used the Ukrainian emblem, “Volodymyr’s Trident,” since the 10th century.

The double-headed eagle, which became the Russian coat of arms during the reign of Prince Ivan III, has a long but foreign history. The image of an eagle with two heads, symbolizing the sun, can be found on ancient Sumerian seals. However, the symbol’s greatest fame dates back to ancient Rome, when it was used by the Byzantine emperors of the Palaiologos dynasty (13th–15th centuries). Since Russia saw itself as the successor to the Orthodox Byzantine Empire, previously part of of the Roman Empire, tsars began to use thedouble-headed eagle as a symbol of the state’s greatness and nobility. Tsar Ivan III, who was married to the niece of the Byzantine emperor, Sophia Palaiologina, approved the image of a double-headed eagle as Russia’s coat of arms. Hence, the Russians started to refer to their country as the so-called “third Rome.”

In the context of appropriating national symbols, the approval of the Russian flag in 1669 is a rather conspicuous event. This story is related to tradecraft. The Dutch engineer who oversaw the construction of the Russian ship “Orel” asked the Tsar to provide a state flag to be flown on board. Unaware of the national flag’s significance, Tsar Alexis Mikhaylovich copied it from a Dutch ship; in 1720, Peter I simply changed the order of the stripes.

The Russian national anthem adoption is an interesting story too. Regardless of the state name, Russian national symbols were often borrowed. In the Russian Empire, “God save the Tsar” had the same melody as the anthem of the British Empire, “God Save the King”. After 1917, the Soviets used “The International,” with lyrics written by the French revolutionary Eugène Pottier. The Soviet national anthem, first appeared in the 1940s, and its melody is preserved in the current Russian one. During WWII, the patriotic and rather symbolic song “Arise, Great Country” was popular throughout the Soviet Union. Russian composer Alexander Alexandrov allegedly written the melody, but Ukrainian composers and musicologists claim,that it is too similar to Ukrainian composer Mykola Lysenko’s “Epic Fragment.” Moreover, it is pretty likely that “Arise, Great Country” is based on “Arise, My People!”— the song of the Kryvyi Rih rebels from the Ukrainian People’s Republic.

Stolen Culture

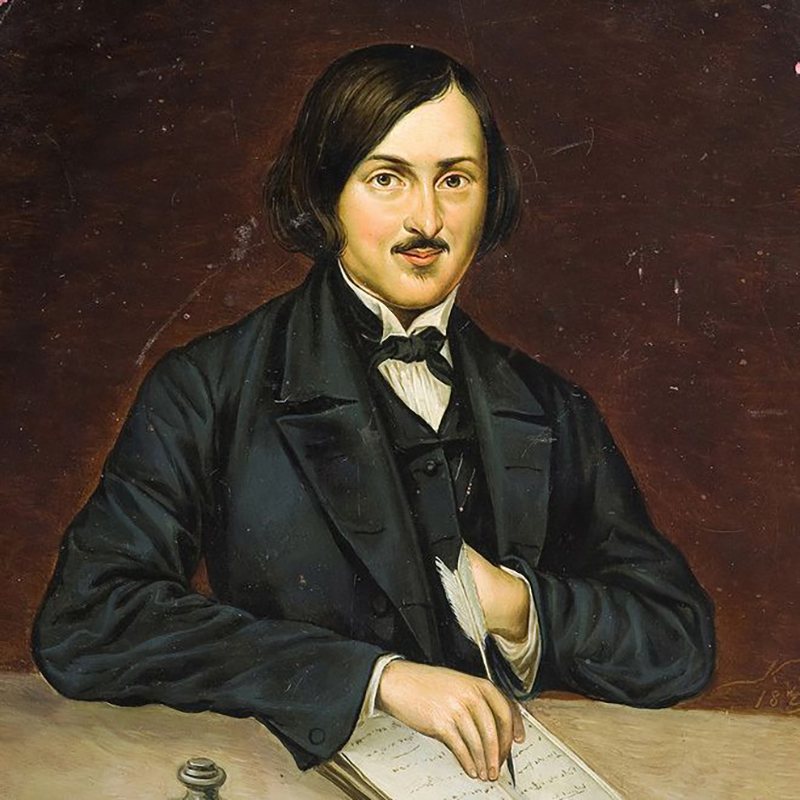

Russians eagerly add the cultural achievements of others, particularly those of Ukrainians, to their own list of accomplishments. In 2021, the Russian Center for Science and Culture in Kyiv, a branch of the Russian state agency Rossotrudnichestvo, managed to call Taras Shevchenko a “Russian-Ukrainian poet.” As the staff explained to the outraged public, Shevchenko has some works in Russian, which means he is a Russian poet. For a long time, Russians have been repeating the same rhetoric about Hohol and Bulgakov. And, even if Bulgakov did put anti-Ukrainian statements in the mouths of his heroes, Hohol clearly demonstrated his admiration for Ukrainians (like in his novel “Taras Bulba,” 1835). Mykola Hohol was interested in ethnography and collected Ukrainian folklore. He also wrote in a letter to ethnographer Mykhailo Maksymovych:

— Really, leave katsapiia (slur for Russia – ed.) and head to the hetmanshchyna (territory of Ukrainian state of the time – ed.). I am considering doing the same and plan to leave next year. We are fools if you think about it! Why and to whom do we sacrifice everything? Let’s go!

Statements like “they wrote in Russian; therefore, they’re Russian” sound especially cynical, given that writing in Ukrainian was

prohibited in the Russian Empire.

On the other hand, Russia is not eager to refer to those Russian writers identifiying as Ukrainian as Ukrainian-Russian writers. Thus, the writer Anton Chekhov was born in Taganrog, an ethnic Ukrainian territory and identified as “maloros” in 1897’s official census. Words like “maloros” and “khokhol” in the 19th century were not perceived as a slur, and Chekhov himself said: “Ukrainian blood flows in my veins”. In his autobiography, the writer wrote about Taganrog’s Ukrainianness. Soviet scholars later removed this mention. In his letter to the Ukrainian historian and linguist Ahatanhel Krymskii, the writer describedhis attitude towards Ukrainians: “Ukraine is dear and close to my heart. I like its literature, music, and wonderful Ukrainian song, so rife with enchanting melody. I love the Ukrainian people, who gave the world such a titan as Taras Shevchenko.”

Peter Tchaikovsky’s case is also interesting. He happens to be a descendant of the ancient Ukrainian family of Chaikas. Moreover, the Tchaikovsky family was related to such Ukrainian families as Hrebinkas and Hohols. In his youth, the composer often visited Ukraine in his youth, stopping in Trostianets and Kamianets. Podillia was a special place for Tchaikovsky. He created, many musical works on Ukrainian themes there, including “Cherry orchard near the house,” “Blacksmith Vakula,” and “In the garden, near the ford.” The Russians, however, deny Tchaikovsky’s ties to Ukraine, emphasizing instead his contribution to the “grand Russian culture.” The Kremlin has been speculating endlessly on Tchaikovsky’s work and strongly tied it to Russia’s imperialist narratives.(The composer became one of the 1991 Russia’s August Coup’s symbols, as the citizens listened to Swan Lake on the TV on repeat while the state was falling apart in Moscow. Russian propaganda machine ideologized composer’s figure to such an extent that today it seems to be an arduously difficult task to start discussions about his Ukrainianness.

"Chumaks in Malorosiya (Little Russia - ed.)," Ivan Aivazovskii.

We also witness thefts in painting. Not only do the Russians claim Arkhyp Kuindzhi and Ivan Aivazovskii as “their” artists, but they also stole their paintings from Mariupol’s museums during the full-scale invasion. The Russians are also attempting to fit Kazymyr Malevych, born in Kyiv and lived in Slobozhanshchyna’s towns and villages, into the paradigm of the “Russian world.” He is labelled as a Russian artist only because he spent some time working in Russia. According to Dmytro Horbachov, the researcher of Malevych’s work, the artist had a moral stance on the Ukrainian identity: when filling out questionnaires, Kazymyr Malevych wrote “Ukrainian” in the “nationality” column. Also, the Holodomor theme, which was taboo in Russia at the time, appeared in the artist’s suprematist paintings.

"Peasants," Kazymyr Malevych.

Another manifestation of Russia’s expansion is marking canvases depicting Ukrainian traditions as Russian. A painting by French impressionist Edgar Degas depicts three girls dancing in Ukrainian national costumes. For a long time, the canvas was called “Russian Dancers.” It was only during the full-scale Russian-Ukrainian war that the National Gallery of London, at the request of Ukrainian art critics, renamed the impressionist’s painting to “Ukrainian Dancers.”

“Ukrainian Dancers,” Edgar Degas.

National Cuisine

Just like Russian culture, the country’s gastronomy flaunts similar baggage of borrowings that have become entrenched in the Russian mentality as a local heritage. First, let’s mention borshch and varenyky, two apparent components of the Ukrainian culinary canon, depicted in the national classical literature and ethnographic works. The Soviets practised others’ national characteristics assimilation, and modern Russia continued that tradition. As a result, “Russian borshch” can be frequently found on the Internet and international restaurants’ menus, while Russian sources often claim that the dish has a “common Slavic” ancestry.

To ensure that the world recognizes borshch as Ukrainian, culinary expert and chef Yevhen Klopotenko promotes dish’s history. He took part in an expedition across Ukrainian regions in search of original recipes and ensured that borshch was mentioned in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List. When discussing the national soup of Russians, it is worth mentioning shchi, says Russian historian of the 18th century Ivan Boltin:

— It is known to many who have not visited Russia that the Russians’ special and favourite dish, among all others, is shchi, while the Maloroses, nobles and peasants alike, prefer borshch. They consume it almost daily, with the difference that the rich prepare it better than the poor.

Varenyky, which Russians claim they invented and spread worldwide through Poland, is known as “pyrohy” by Poles and Ukrainians living in western Ukraine. This dish originated in Halychyna and made its way to Poland. Traditionally, varenyky play an important role in Ukrainian folklore. According to ethnographic research, on Saint Andrew’s Day (celebrated on December 13), women used to predict their future with the help of this dish.

— On Saint Andrew’s Day, the girls cooked pyrohy, and later laid them out in front of a hungry cat. If the animal chose the girl’s dumpling, then the girl had to prepare for her wedding. If the cat just bit off and left the dumpling, it was an omen of divorce and loneliness.

Varenyky were traditionally given to Ukrainian mothers — shortly after delivery as a symbol of fertility and procreation. They also symbolized the new moon, representing the feminine principle in Ukrainian tradition.

The origin of “Russian pelmeni” is quite intriguing: the meat dumplings were actually brought to Russia from Asia. Some sources indicate that China is the birthplace of this traditional Russian gastronomic dish. According to other historical records, the recipe for pelmeni was spread by the bellicose Mongols as they conquered new lands.

Goods and Equipment

Due to economic sanctions imposed on Russia for its aggressive invasion of an independent state, the shortfalls of Russian production are becoming visible to the public eye. The Russians had even imported nails, according to the Chairman of the Russian Federation Council said. Soon, we’ll see the consequences of import substitution, which, has been a long-standing trend in Russia. After the end of World War II, USSR transported many important industries from the East Germanyto its territory.

The popular Moskvitch 400 car was manufactured at an “exported” Opel factory, and it was an exact copy of the German Opel Kadett K38. Another classic example of the Soviet automobile industry, the Zaporozhets, owed its appearance to the Italian Fiat-600 car. Same goes for Soviet motorcycles known as “Ural,” copied from the German BMW-750.

The creation of copies under the Soviet branding also included the production of foods and beverages. With the assistance of the CPSU, the All-Union Research Institute of Beer and Non-Alcoholic Drinks created an analogue of the famous “Coca-Cola.”

It was then that they started to produce the soda called “Baikal”.

Borrowings were also required during the Moscow metro’s construction. Since the USSR had no experience in creating such structures and lacked the funds to attract foreign experts, Khrushchev ordered from the Brits a single copy of a tunnelling shield (a structure used during the tunnels excavation). After learning the intricacies of construction, the USSR simply copied the Western models.

The Soviet weapons industry is also rife with similar stories. The Kalashnikov rifle, considered the hallmark of Russia’s arms industry, is also borrowed. “Kalash” was based on Hugo Schmeisser’s design of the German rifle StG 44. In the USSR, Schmeisser personally led the development. According to Soviet and later Russian propaganda, Mikhail Kalashnikov, who had no engineering education and graduated from a rural school in the seventh grade, was the architect of Russia’s arms pride.

Despite its vast territory and ongoing violent attempts to establish a “Russian world” on the territories of other states, Russia is scattering its resources in an attempt to establish its cultural and territorial hegemony. Today, the country has taken things further by depriving Ukrainians of their cities, houses, and, most importantly, their lives.