The Holodomor as a genocide of the Ukrainian nation organised by the Soviet regime had enormous consequences for Ukrainians. However, the scale of the trauma experienced and the changes that it brought can’t be placed in a history textbook and put away into cold storage. The degradation of values and viable demographic changes caused by the genocide, cast grim shadows on the next generations. Nowadays, historians, psychologists, and anthropologists all insist: the consequences of the Holodomor can be still felt in Ukrainian society at various levels. Those consequences manifest themselves primarily in the issues of privacy, security, family customs and attitude towards the concept of private property.

Popular culture keeps cultivating the jokes about grandmothers who always find an opportunity to give their grandchildren a “penny”, who bake lots of cakes and do their best to make sure their grandchildren are not hungry. These jokes evoke childhood memories and nostalgia in people, just like the old cupboards where our grandmothers kept their stock of supplies for a rainy day. Although it is unlikely that these people witnessed the tragic events themselves, they became affected by the changes caused by the Holodomor in 1932–1933, as did the current generation.

“The biggest aftermath of the Holodomor that Ukrainian society still faces today is the fact that it’s not yet a matter of the past. Three, four generations after the Holodomor survivors people still experience the influence of this transgenerational trauma—at a much deeper level than they themselves realise”, — Oksana Zabuzhko, a writer.

In the 1920s the Soviet Union established itself as a totalitarian state with a communist ideology. The new socio-economic structure didn’t have a place in its hierarchy for a Ukrainian farm owner. A typical citizen of the Soviet Union was an impersonal comrade with no nationality, property, family ties or personal values. The population, which the state was trying to gradually enslave, resisted such changes. The state went all the way in its yearning to break the back of the nation through uprooting the Ukrainian village. They confiscated all kinds of provisions, even the cooked and served meals from people’s tables. Then they cut off the access to supplies and banned any moving in or out. Millions of Ukrainians lost their lives because of the Soviet regime policy, which was aimed at them. Today this crime is classified as a genocide against the Ukrainian nation.

Not only did the Holodomor alter national demographics, but it also had a huge impact on people’s values. The aim of the Soviet communist totalitarian regime was to concentrate all the resources in the state’s possession, to break the nation’s back by turning Ukrainian farm owners into impersonal kolhosp members. These changes were supposed to forcibly create a new outlook of a new Soviet citizen, and in the case with rebellious Ukrainians in the cruellest way possible — through slow annihilation by starvation.

Starvation influences the physical and psychological state of a person and changes one’s personality. In the case of the Holodomor, the trauma remained unexpressed and existed only in family narratives. Today Ukrainians are called a “postgenocide society”. Therefore, the objective for the current generation is to comprehend the scale of the changes that took place in the 1930s, and to find an approach on how to live with them in the 21st century.

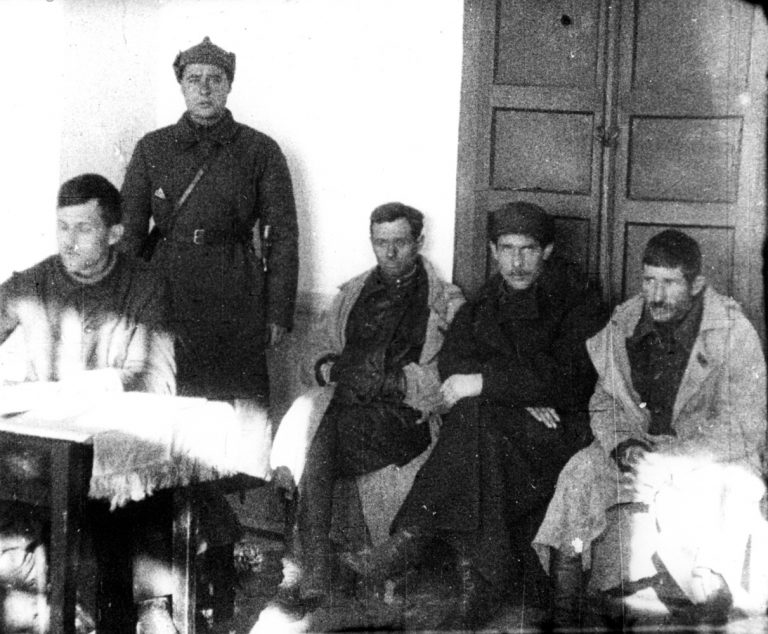

A so-called “living newspaper” theatrical performance "Stalinets" in the J. Stalin community centre of Mezhova village, Dnipropetrovsk region, 1933.

Distrust, passivity and fear

The Holodomor altered the values of Ukrainians and resulted in a new type of individual according to the researcher Serhii Maksudov:

— This individual was passive: they obeyed and fulfilled the most absurd orders of authorities; such an individual was ready to work for the lowest salary or for no pay at all, didn’t appreciate the job, had low self-esteem, lived fearing the unknown, tried breaking the law whenever it was possible and considered theft a natural way of property redistribution. This individual had no self-respect. Such ethical qualities like a humane attitude, compassion, the feeling of love towards family and neighbours were weakened or were replaced by fear and hunger. At the same time, the individual took part in all official state events and believed that they were legitimate and ignored the discrepancy between the Soviet slogans and reality (for instance, when a non-anonymous vote for a single candidate was called “elections”, poverty was called “thriving” and so on). Orwell was right, when he called this schizophrenic bifurcation of the totalitarian state “doublethink”.

The perpetrators of the Holodomor belong to a circle of people from the Kremlin — Stalin, Kahanovych, Kosior, Molotov, Postyshev, Chubar, Khatayevych and others. By their orders special brigades were formed in the local communities that took away from Ukrainians any food and thereby condemned people to starvation. Heads of kolhosps, heads of village councils and their subordinates, kolhosp workers, Komsomol members and even vagabonds and drunkards turned into “activists” who eagerly destroyed any kind of provision during their raids. However, there are a lot of stories from witnesses about the heads of kolhosps who did their best to save the lives of their fellow villagers. By doing so they put themselves under threat of exile or execution. It should be remembered that the distribution of grain as a benefit in kind during the grain procurement campaign in 1932-1933 was considered theft of state property and led to criminal liability. The members of the demoralised society reported their neighbours, relatives or their rescuers to the authorities, in order to get at least some minimal reward. It formed a total distrust of each other. Most of the people who were reported to the authorities in 1932-1933, later on, fell under mass repressions in 1937-1938.

Victoriia Horbunova, a psychologist. Photo by Valentyn Kuzan.

“People who were immediate participants in the events, people from a generation before us, they were not innocent angels and poor victims. There were a lot of heroic cases of self-sacrifice, but they were all different. We have to accept that there were different people in our own families who acted differently in order to survive and save their family. We need to speak about things like that in order to understand why it happened. There can’t be just black or white but it is a combination of all colours on a palette. These stories have to be authentic; they shouldn’t be only two-dimensional where we either turn somebody into a hero or a victim”, — Victoriia Horbunova, a psychologist.

Among recollections of the Holodomor witnesses, we can often notice accusations against the “authorities” as a group rather than against specific people. They admit that the policy of the Soviet regime was aimed against Ukrainians. The Holodomor witnesses tell stories about themselves and their relatives that managed to survive in the territory of Russia where famine wasn’t so severe. The population was either not informed about the reasons for severe measures or they were narrowed down to economic ones. The actions of the authorities were contradictory. The recollections of Semen Ovechka from the village of Volodymyrivka, in the Melitopol district (today, the Yakymyvskyi district of the Zaporizhzhia region) confirm it:

— At first, they announced that wealthy farmers were enemies of the state. Later on, they announced that poor farmers were also enemies. The rich ones were called “kurkul” and those less wealthy were called “pidkurkulnyk” (a person who supported a kurkul). Then they came with expropriations to the poor farmers. So it was their system — gradually go after each social group. I think their final goal was Ukraine as the whole; they wanted to break the country’s resistance, to turn Ukrainians into slaves so that they could get from them whatever they wanted. I think they really wanted to bring Ukraine to its knees.

Speeches at party congresses and meetings were recalled by the party members themselves:

“He (the secretary of the party district committee) believed that the party would lose its prestige if he started speaking with people using plain language. He knew that we, the kolhosp workers, received 100 grams of provision for one full workday, but he kept reiterating over and over again that compensation for one workday and wellbeing, on the whole, kept increasing each year. Just try to disagree with the district authorities; it seemed that they gave you a piece of advice or a recommendation, but it was an order, in fact”, — a quote from a recollection story by Oleksandr Yashyn, a writer.

All these contradictions, omissions and the irrefutable authority of those in power led to the idolisation of the system. The reasoning behind it had nothing to do with respect, yet it was an opportunity to survive and save one’s own people.

slideshow

Values established in the 1930s continue to prevail in modern Ukrainian society. According to a study of the SOCIS group safety is utterly important to Ukrainians today. By “safety” is meant avoiding stress from novelty, searching for a “safety net” in all spheres of life (through useful social connections or savings), tactical thinking aimed at survival, egoism and closeness. Next, they name kindness and moral universalism. It means that people don’t care about the wellbeing of their immediate circle or society as a whole, and have a sense of social injustice and inequality instead. Technically it is the mentality of the Soviet citizen — a broken and traumatised personality — that still has great influence on our decisions and perception of reality.

“People became more careful and way more selfish. It became clear that personal survival was of the greatest importance. Obviously, survival had the same significance in the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century for many other nations. However, this tendency began to change. In Ukraine, it hasn’t changed to this day. Survival remains to be a core value for the majority of our fellow citizens. It is also true for Ukrainians who were born after Ukraine proclaimed its independence”, — Vitalii Portnykov, journalist.

Today TV shows simulate extreme situations in the streets to watch people’s reaction and actions. And for the passers-by in Ukraine it is very typical just to keep going, minding their own business, putting a mask of indifference on their faces, avoiding the situation and trying not to be involved. Such indifference is deeply rooted into the nation’s tragic history. During the Holodomor parents had to watch their children die, being unable to help them, there were cases of cannibalism in the villages and the deceased were buried in the earth cellars since people had no energy to dig out a grave. All these things took place next to deep-laid physical and psychological changes that each person’s organism experienced due to the long-term state of hunger. Under circumstances like that humanity, friendliness and affection lost any meaning and significance. The villagers turned into passive observers of perishing in slow motion.

Being passive and inert in response to human suffering reflected on people’s perception of the world and their interactions within private and public environments. For instance, roads, kindergartens, plants and factories were built on top of the sites of mass graves for the victims of the Holodomor. People continue using these roads and buildings today with indifference to the mass burial of the Holodomor victims under their feet.

Another change is reflected in their attitude towards food. A very careful attitude towards food, leftovers and even crumbs was noted by families of the Holodomor survivors. Some of them had a small bag with dried bread “for emergency cases” and kept it at hand even when big supermarkets emerged in Ukraine. A wish or rather a necessity to have some kind of stash in a pantry or cellar, away from other people’s eyes is typical for modern generations that have a habit of stocking up on food, too.

slideshow

The best example is the spring-fall “ritual” of planting and harvesting potatoes. The majority of Ukrainians have stories about field works at their parents’ or grandparents’ kitchen gardens, where all the family harvests potatoes on a commercial scale. It gets stored in cellars and in spring half of it ends up rotten, because there is just too much of it. Some adjustment to the next year’s planting plans would make sense, but it never happens. The older the generation, involved in field works, is, the less room is left to compromise on planting quantities. They firmly believe that they are planting a product with a long shelf-life and high nutritional value for the whole family. Refusal to participate equals deep personal offence.

The statistics show that more than half of the potatoes grown in Ukraine end up as waste. Approximately 95% of all potato harvest in Ukraine comes from private fields. The price for potatoes even during poor yield seasons stays quite low.

The Holodomor formed another feature — a need to make sure that the younger ones are fed. During the famine, parents were desperately trying to save their children. They were sending them out to bigger towns, nearby villages that were not so badly affected, leaving them in boarding schools that had at least some bits of food. It transformed into baskets with buns and money that grandmothers and grandfathers sneak in for their grandchildren, often for their peace of mind.

slideshow

Private property

“It was always a part of Ukrainian identity what Taras Shevchenko (Ukraine’s most prominent poet — tr.) described as “a cherry orchard near the house”. Ukrainians need something of their own. They need a household, a plot of land to grow not just potatoes but flowers as well. Their distinctive national features (compared to their eastern neighbours) were a settled lifestyle, peacefulness, tolerance, but they also had a clear understanding of how beneficial a teamwork could be in certain circumstances. The combination of a farm owner with the concept of collectivism (an adequate one, not the Soviet version of it) is one of the defining principles of Ukrainian identity”, — Roman Podkur, a historian.

Almost 90% of Ukrainians before the Holodomor resided in rural areas. It meant that they were primarily individual owners that were used to relying on themselves and the results of their hard work. They had a clear understanding that the wellbeing of a family depended on their effort and what the harvest would be like.

With the introduction of the kolhosp system, farmers were paid based on “trudoden” (“workday”, a form of wage payments in kolhosps — tr.). In fact, they were recorded as vertical marks in a notebook (very often a full workday wasn’t recorded as one “trudoden”). When the harvest period was over the kolhosps would receive some grain left after fulfilling the procurement plan. In fall 1932 the majority of kolhosp workers didn’t receive their share of grain for the entire year of work and were doomed to starvation, because the Ukrainian SSR didn’t meet the unrealistic procurement plan imposed on the republic by the state. Disabled kolhosp members would not have any record of work days and they would not receive any retirement benefits. They were supposed to be supported by working family members. People could get money by selling goods harvested from their plots. However, there was less and less land left in people’s property. On top of that, in 1932 the farmers were forbidden to make any sales if they failed to fulfil the grain procurement plan.

Roman Podkur, a historian. Photo by Oleh Pereverzev.

“Bolsheviks treated collective farms as other types of factories and their main focus was to make people work there, farmers in this case. There were two kinds of these “factories”. The first one was “radhosps” (state farms), which had the most potential because the people who worked there had no private property. They were workers on a salary. But their salary was so tiny that they were not interested in the results of their work. The second type was “kolhosps”. The state wanted them to be organised as communes. The main idea behind all this was to buy goods produced by the farmers at the cheapest prices, rather than according to the rules of a market economy. Basically, it was exploitation”, — Roman Podkur.

Collectivisation and dekulakisation were aimed at depriving an individual both of land and home. In case of missing a day at kolhosp, anyone could be thrown out of their home or the whole family could be sent to Siberia. The kolhosps demanded complete dedication for the sake of social wellbeing. At first the kolhosp members received a food ration; however, later on even such insignificant payments were seized. The farmers were made to work for free and were also deprived of any other provisions.

It caused massive numbers of farmers to resign from the work in kolhosps after the first waves of compulsory collectivisation: they took back their tools, livestock and grain. On the 7th of August, 1932, a resolution “On Safekeeping the Property of State Enterprises, Collective Farms and Cooperatives, and Strengthening Public (Socialist) Property” appeared. It is widely known as “the Law of Five Ears of Grain”. For theft of collective property anyone could face execution, or, under “extenuating circumstances”, an individual could get imprisoned for 10 years. Under “the Law of Five Ears of Grain” people were forbidden to collect any crop residues from the fields.

Once wealthy owners, the farmers found themselves in a situation where they couldn’t support their families anymore. The requirement to work for free, to invest all resources into quality development of the state-controlled economy under the threat of starvation broke the basis of entrepreneurship based on ownership. A farmer turned into a passive executor of state directives because it offered vague opportunities to save their families and themselves from death.

Families used to unite around their homesteads. The destruction of private property and the Holodomor undermined the family as a core value. During famine some parents, unable to save themselves, would leave their newborn babies or young children at the village council doors, at the railway stations or on benches amidst the towns, in a hope that mercy of some kind-hearted and better-to-do people would save their kids. Some of those children ended up in orphanages, which also lacked food and turned into places of death rather than places of refuge. There were no incentives to devotedly work in the interest of the state, and people became indifferent. It meant any aspirations to develop private farms and property were futile.

Theft became the only possible way to survive and collective property was viewed as something that could be taken or stolen. Collective responsibility meant that nobody was really responsible. Such a mindset still exists in Ukraine and is applied to the theft of state or public property, just like bringing a small but stolen item from work. However, private property is still a taboo and falls under the rule “stealing is bad”. That’s why common areas like apartment building entrances, areas around them and municipal infrastructure look shabby and unattended. A similar attitude applies to collective work — if there is no appointed manager or a supervisor, there is no responsibility, because no one “owns” the results.

“Bolsheviks tried to create an alternative village and kolhosp community. The collective property consisted of confiscated livestock and premises that belonged to the kolhosp. However, the kolhosp members didn’t feel it was theirs. That’s why cattle were often not milked and not fed. The attitude was, “It’s not mine. It’s a collective property”. Attitudes like that have changed everything in people’s mindset and their attitude to property” — Roman Podkur.

“It is believed, for example, that it’s not worth doing anything outside my family or my home. People don’t have this basic feeling of security that occurs when one lives in the same place for a long time, with nothing bad happening, without any threats to one’s family, that would force them to move. So from people’s perspective it only makes sense to do anything within their immediate place of living, but not around it. Because there’s always a possibility that anything around them can get ruined at any moment”, — Victoriia Horbunova.

Grain weighing in the kolhosp named after Lazar Kahanovych, Dnipropetrovsk region, the Mariivka village.

Stashing provisions underground, concealing any hints that one could sustain himself, being unresponsive to any humiliations were some of the ways to survive during the Holodomor. Anyone could be called a “kurkul” or “pidkurkulnyk” for any manifestations of prosperity. To let anyone know about one’s grain or provision deposits meant they would be confiscated. That’s how farmers learnt to hide both personal achievements and a piece of bread.

“People were afraid to stand out, to be different. The villages were resettled. People were mixed so that there were no groups that shared the same experience. Because I can talk about those things that are so intimate only with those who had the same experience, I trust them. This circle of trust was ruined”, — Victoriia Horbunova.

Today in such typical Ukrainian proverbs like “welfare loves no exposure” one can sense the influence of the Holodomor, when it was important not to stand out, to be like everyone else, not to demonstrate any achievements and not to attract attention. This concept undermines any initiative and consequently an opportunity for the development of private property “unlike everyone else’s”. As a result it makes impossible the development of businesses or career growth.

The farmers of the Illintsi village in Vinnytsia region are giving away their produce to the state, 1929.

A national trauma

Almost 90% of Ukrainians lived in rural areas at the beginning of the famine. The Holodomor-genocide was organised against the village as a source of traditional culture and customs. Some of Ukrainian villages were turned into closed zones after the introduction of “black boards” (or “boards of infamy”) in 1932 and imposing of travel restrictions in 1933. People who were doomed to death were deprived of any connection with the outside world.

Cities were perceived as the only place to survive under the given circumstances. However, they suffered from famine as well and the streets were filled with bodies of escapee villagers, who had starved to death. And yet, to the unsuspecting the city seemed an attainable chance for refuge. With the development of factories, large-scale production was concentrated there. It was an opportunity for people to earn a living and survive. Russified cities cultivated a complex of inferiority in Ukrainians. They became “melting pots” where it was easier to engineer the right kind of a Soviet citizen. The Soviet propaganda was reiterated over and over again: factories are the engine for the state’s progress.

Vitalii Portnikov, a journalist. Photo by Oleh Pereverzev.

“The fewer there remained of the people who were the bearers of these archaic, rural traditions, but who could still modernise these archaic rural traditions in a big city and make this big city modern and Ukrainian, the greater was the further development of the empire. Stalin simply laid the foundations so that there was no Ukrainian threat at all”, — Vitalii Portnikov.

The tendency to leave the country for the city is neither new nor unique for Ukraine. However, there is a tendency to devalue the village in Ukraine even today. Being a village inhabitant in the 1930s meant being a slave: villagers did not have the right to obtain identity papers, and could buy a train ticket only with the permission of the supervisor and head of the kolhosp (it was almost impossible to obtain this permission). A village continues to be associated with stagnation and lack of prospects, even though for Ukraine today the villages present an opportunity to attract investments and to develop businesses and tourism.

Moreover, Ukrainian language and culture were strongly associated with villages and something rural. Speaking Ukrainian meant revealing one’s identity and a chance to displease the state. Demonstration of one’s identity threatened the cohesion of the Soviet state and was a reminder why the Ukrainian population was doomed to starvation. To acknowledge oneself as a Ukrainian meant to acknowledge oneself as an unproductive and second-class villager or even to face annihilation together with the Ukrainian village. To be ashamed of national identity and to attribute Ukrainian features exclusively to rural areas is a tendency that persists today, as well.

“The fact that we still don’t have a real Ukrainian [speaking — ed.] Kharkiv, a Ukrainian Odesa, the fact that we don’t have a Ukrainian Dnipro and a Ukrainian Kyiv means that we don’t have a single real Ukrainian million-plus city. This is a direct consequence of the Holodomor. Million-plus cities form modern civilisation, they are what allows a country to resist foreign influence, the influence of another world, the “Russian world”. So I must say that Stalin’s idea of the Holodomor was effective not only in terms of physical, but civilisational annihilation of the Ukrainian nation”, — Vitalii Portnykov.

Hanna Humenchuk, born in 1929. She survived the Holodomor at the age of 3. Photo by Valentyn Kuzan.

Silent victims

“It is important to keep this conversation going, to tell those previously untold stories. It was a surprising observation to make, that the families which were avoiding the Holodomor narrative had more of their immediate family members among the victims of famine, than the others. Also people in such families demonstrate negative prejudice and devaluation of those events more often. Their common response is “I don’t think it’s worth stirring this up again”. But this has to be a live conversation”, — Victoriia Horbunova.

The first reference to the Holodomor in the Soviet mass media appeared only during the “perestroika” period (from the second half of the 1980s), when it could not be silenced any longer. The crime of genocide was witnessed by millions of survivors and became their trauma. At the same time, the communist totalitarian regime hid all evidence of the crime: statistics were falsified, extinct villages were inhabited by other people from various regions of the USSR, and the new roads were built over mass burial places. To speak and resist meant to endanger one’s family. The witnesses survived, but kept quiet, because publicity cost dearly.

“Ukrainians did not have their own state. They were citizens of the very same state that annihilated them once and was willing to do it again. And there was no one to stand up for them” — Vitalii Portnikov.

Only in the mid 1980s, when the glasnost and transparency policy allowed Soviet citizens to publicly discuss social and political problems, were the victims allowed to speak.

Oksana Zabuzhko, a writer. Photo by Oleh Pereverzev.

Psychological and physical trauma remained undiscussed. Most of the Holodomor witnesses died knowing that the perpetrators were not punished.

“This is not just a taboo topic, but a topic sealed with fear: not only did the state kill people’s ancestors, it forbade to mourn the deceased under the threat of death” — Oksana Zabuzhko.

“To speak again meant for people to put themselves back in the situation of survival on the brink of death. It meant to trigger the intrusive memories — when people lacked the awareness that those were things from the past, and experienced the events as a threat in their present. Such intrusive memories made people live through those tragic events again, see their loved ones dying, see those bloated bodies as if that nightmare became real once again. Many of them were also left with distorted or displaced perception of reality — the result of disparity between the official Soviet propaganda statements and their own memories”, — Victoriia Horbunova.

Only in 2010 did the Kyiv Court of Appeal name the perpetrators of the genocide during the trial. Such silence and fear of speaking affected the personalities of those who managed to survive.

The generation born after 1933 listened to family stories, and for their children and grandchildren these were only distant echoes of the past. At the same time, the consequences of genocide for Ukrainian society are firmly rooted in daily life and, due to fear, are still not fully spoken about and comprehended.

“The Holodomor has driven Ukrainian society into this unspeakable horror, especially when it comes to ordinary people. Even in late Soviet times, nobody dared to mention the Holodomor” — Vitalii Portnykov.

slideshow

On top of that, the unexpressed nature of the trauma was coupled with suppression of an individual position or point of view. In 1937-1938, after the Holodomor, there was a wave of repression in the Soviet Union against workers of culture and education. The Soviet system destroyed anyone who dared to oppose it or express their own opinion. The Holodomor destroyed faith in joint social action. Under the conditions of the formation of the Soviet “Newspeak”, the events were not named directly, and the true meaning was hidden behind long sentences of documents and speeches. Even in the orders among party figures secrecy and indirect phrasing was preserved. That is why even today many people so often avoid answering controversial questions about power and politics directly.

“Changes in discourse alter reality. While we still had the first generation of direct witnesses and could have these post-traumatic reactions and post-traumatic disorder, people avoided talking about it. And these were mutually supportive things: on the one hand, the factor of psychological avoidance directly related to the trauma, and on the other hand, there was propaganda” — Victoriia Horbunova.

Nina Ivanivna Trostianenko born in 1926. She survived the Holodomor at the age of 7. Photo by Valentyn Kuzan.

By the end of 2020, the Holodomor has been recognised as genocide by 17 countries, including Ukraine. Such traumas leave their mark not only on the values of their eyewitnesses, but also on the values of entire generations. More and more archives are opened, more and more documents confirm the words of thousands of witnesses and new details of the crime committed by the totalitarian communist regime are revealed. Therefore, it is important to comprehend all these experiences and this trauma and to integrate them into today’s society development.

“We have to explain. A person must understand that some behavioural strategies, some thoughts and beliefs do not coincide with reality, they fail testing by reality. Why does it happen? Because they are guided not by this reality, but by that traumatic reality” — Victoriia Horbunova.

supported by

Матеріал реалізовано в рамках проєкту «Голодомор: мозаїка історії» разом з Національним музеєм Голодомору-геноциду за підтримки Українського культурного фонду