For centuries, homegrown plants and fruits sustained generations of Ukrainians. The cultivation of different varieties of grapes led to the development of winemaking in the region, with products that had the potential to spread far beyond the country’s borders. However, the history of Ukrainian viticulture and horticulture was largely influenced by centuries of Russian colonialism, specifically the rules imposed first by the Russian Empire and later by the Soviet Union. The occupiers in Moscow did not only disapprove of talented, disloyal-to-the-regime Ukrainian researchers; they also disliked Ukrainians owning private property and having opportunities to feed themselves from homegrown crops. In this piece, we will explore the cultivation of vineyards, gardens, and orchards on Ukrainian lands before and after the intervention of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union.

Due to repression and persecution, Ukrainian horticulture and viticulture have lost a lot of specialists and skilled landowners, whose land plots became public property. Orchards and vineyards were also destroyed indirectly, such as by the construction of dams and reservoirs for hydroelectric power plants. Legislative decisions, like agricultural taxes or Mikhail Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign, also reduced their number.

In addition to directly harming certain Ukrainian orchards and vineyards, the Russian Empire and the USSR took control of others. At different times throughout history, they invested resources into increasing planted areas, breeding crops, and classifying fruit varieties. Yet, the colonised peoples were not allowed to claim recognition, profit, or other goods from this labour, let alone the freedom to make decisions or develop internationally known brands under a Ukrainian banner.

Photo: Irynka Hromotska.

Ukrainian vineyards

Before Russian influence

The history of grape cultivation in Ukraine stretches back to ancient times when the Greeks populated the south of modern Ukraine.

They brought not only vines, but also the culture of winemaking. Vineyards were actively grown in Crimea and on the coast of the Black Sea. These territories became one of the essential viticulture regions for all of Europe. The ancient history of Ukrainian winemaking regions, as well as stories about those who are currently developing winemaking in Ukraine, are the focus of The Untold Story of Ukrainian Winemaking by Serhii Klimov. This book is currently available in Ukrainian, but we are working on translations into other languages and are open to partnerships with publishers from various countries to share this untold story with the world.

“I always asked myself: how is it that in Ukraine, where grapes have been cultivated and made into wine for thousands of years, the winemaking industry now needs to be rebuilt almost from scratch?” writes Serhii in his book. It’s true that during the period after Greek colonisation, back in the 9th century during the time of Kyivan Rus, grapes were cultivated in monastery orchards. The local wine produced by monks began to be used at liturgies and consumed at the feasts of princes and nobles.

When Ukrainians started to engage in winemaking on the territory of the Kozak Hetmanate, this culture gained a new momentum. The Kozaks were sufficiently familiar with wine: in the mid-18th century, they consumed a lot of Crimean wine, purchasing about ten thousand buckets per year. By modern standards, this is equivalent to nearly 164,000 bottles annually.

Hetmanshchyna (The Kozak Hetmanate)

A Kozak state that formed in the 17th century on the territory of Ukraine after the Khmelnytsky Uprising, the largest Kozak uprising in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. It existed until the mid-18th century.Cossacks in Crimea, which was part of the Ottoman Empire until 1774, traded with the Ottomans and successfully adopted winemaking practices. Numerous historical sources mention the existence of vineyards at the hetman’s residences in Baturyn and Hlukhiv, and the German researcher Peter-Simon Pallas, who travelled through the territory of Ukraine, confirms that there were vineyards on hills and the banks of reservoirs.

Ottoman Empire

The Islamic monarchical state of the Turkish Ottoman dynasty that existed from 1299 to 1922.

Photo: Yurii Stefaniak.

During the Russian Empire

As The Untold Story of Ukrainian Winemaking explains, when the Russians gradually annexed Ukrainian lands in the 18th century, the Kozak traditions of viticulture began to decline. The Russian Empire destroyed the autonomy of the Kozaks, depriving them of the right to develop their farms. However, even after the liquidation of the Zaporozhian Sich in 1775, the Kozaks continued to cultivate grapes, albeit with restrictions. They had volume limits on the production of vodka from grape pomace (the residue that remains after pressing grapes). They could only produce it for their own consumption, and not for sale, as before.

Then the empire’s attempts to revive winemaking began, but only in favour of the invaders. During the reign of Peter The Great, the number of vineyards on Ukrainian lands increased; planting vineyards and winemaking brought great profits to the imperial treasury.

To increase production and lower wine imports, the Russian Empire allocated funds for viticulture and winemaking, promoting the sale of local alcohol. In the 18th century, many immigrants from Europe were invited to Ukraine and granted autonomy, freedom of religion, and exemption from taxes upon arrival. But such opportunities were not given to Ukrainians who wanted to grow grapes for sale.

Therefore, Austrians, Hungarians, Germans, Swiss, Bulgarians, and others started living and cultivating grapes in Crimea and the Black Sea region. Nevertheless, their efforts were somewhat ruined by a phylloxera infestation in 1857, an insect pest that affected many vineyards in Europe and Ukraine.

At the time of its collapse, the Russian Empire had 125,000 hectares of vineyards, more than half of which belonged to small farms.

Photo: Yurii Stefaniak.

During the USSR

After the phylloxera infestation, Ukrainian viticulture slowly recovered. But under Soviet occupation in the 1920s, private wineries gradually disappeared, and the local elite in the Black Sea region and Crimea — which included the winemakers in the area — was destroyed.

The Soviets created radhosps (state farms) and wineries that produced cheap wine, prioritising quantity over quality in grape cultivation. The authorities monopolised every stage of the process, from production to the sale of alcohol. This approach undermined Ukraine’s potential in global winemaking, reducing its wine culture to a simplistic product for mass consumption.

In addition to prohibiting Ukrainians from owning private property, the newly arrived Bolsheviks also deprived Ukrainians of the opportunity to develop family winemaking. They disrupted the transmission of knowledge from one generation to the next, erasing a long-standing tradition.

Another totalitarian reform that destroyed many Ukrainian vineyards was the anti-alcohol campaign put in place by Mikhail Gorbachev, former President of the Soviet Union. The motivation for this prohibition campaign was the record-high level of alcohol consumption in the Soviet Union at the end of the 1970s. By 1984, the official figure reached 10.5 litres of alcohol per person annually, and when accounting for underground home brewing, it exceeded 14 litres.

slideshow

The prohibition caused tremendous outrage among the population due to the deforestation of vineyards. About 30–40% of Crimean vineyards were destroyed, and rare grape varieties disappeared. Among the Soviet republics, Moldova and Ukraine were most affected, especially the vineyards of Crimea and Zakarpattia.

Fortunately, not everything was cut down. The Soviet Union was large, and officials loved reports, so plants were often uprooted only on paper. In some cases, the oldest sections, whose yields had declined, were removed while younger plants were spared. In other areas, the vineyards were left untouched altogether.

In the late 1980s, annual crops were planted on the sites of former vineyards. The former wineries started to produce oil, syrups, mayonnaise, juices, animal feed, and other products. Some of them simply went bankrupt and closed.

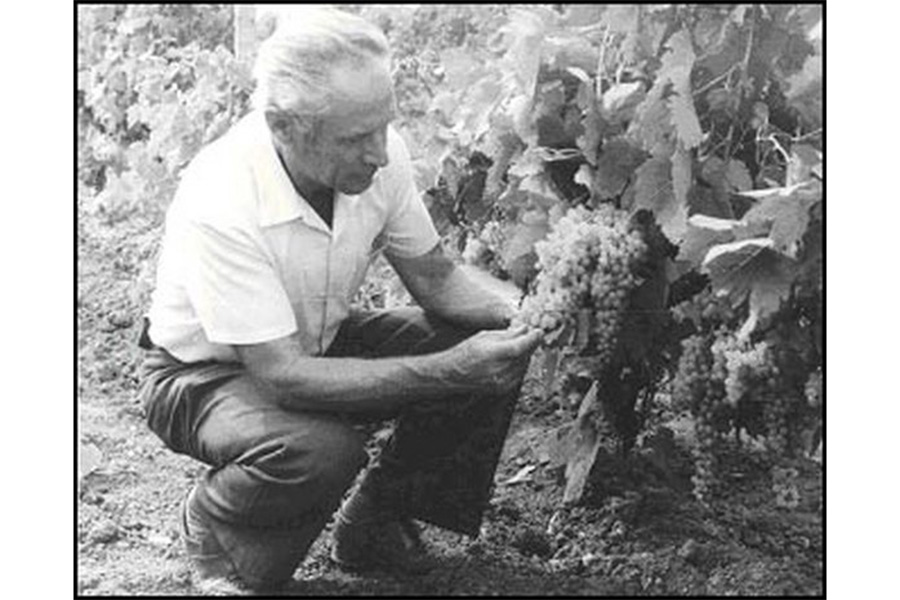

In the south of Ukraine, one of the victims of the campaign was Pavlo Holodryha, a leading biologist and plant breeder, who took his life due to harassment. He was the head of the “Magarach” All-Union Research Institute of Winemaking and Viticulture in Crimea. Throughout his career, he developed 43 new grape varieties, 23 of which were resistant to diseases and pests. The scientist tried to counteract the party’s orders. Due to sabotaging the destruction of vineyards and failing to fulfil management’s orders, Holodryha was stripped of his directorship, and later the grape nurseries at the institute were destroyed. A party and criminal investigation was brought against Holodryha.

Pavlo Holodryha. Photo source: radiosvoboda.org

In Zakarpattia, almost half of all vineyards were cut down during the anti-alcohol campaign. As a result, locals were forced to look for other jobs, and the local winemaking tradition declined significantly. Modern winemakers say that the ill-conceived campaign destroyed not only the vines but also the heritage of generations of Zakarpattia winegrowers and certain local grape varieties that cannot be restored.

The anti-alcohol campaign in the Soviet Union had the opposite effect: there was a quick increase in underground production, home brewing, and alcohol consumption. It also greatly influenced the economy, as the alcohol industry significantly contributed to the state budget. Soviet leaders were forced to abandon the campaign due to the economic crisis in 1987 and the general dissatisfaction of the citizens. Alcoholic beverage sales resumed in even greater volumes than before the campaign.

Ukrainian horticulture

Before Russian influence

The oldest information about horticulture on the territory of modern Ukraine dates back to the times of Kyivan Rus, when fruit trees, flowers, and medicinal herbs were cultivated in monastic and royal gardens and on the lands of wealthy residents. The local foundations of knowledge about zoning and garden planning were established during this time.

Photo: Katia Akvarelna.

Many ancient songs and legends mention orchards in the period of Kyivan Rus, where cherries, pears, apple trees, birches, oaks, and viburnum grew. Various herbs, sunflowers, roses, and rosehips are mentioned as well. This indicates that our ancestors were very familiar with trees and bushes, knew about useful and harmful plants, admired beautiful flowers, and bred them on their estates – not only in Kyiv but in Chernihiv, Volodymyr, Halych, and other places.

During the Kozak period, the culture of cultivating gardens deepened. Kozaks used traditional and European agricultural practices in villages and hetman capitals. They cultivated fruit trees and planted vegetables between rows of tree trunks, which allowed for a larger harvest.

At the same time, a specific Ukrainian baroque style of garden developed on both the right and left banks of Ukraine. These gardens could include large park spaces with terraces, fountains, or even artificial lakes.

Kochubeivsky Park in Baturyn, in the Sivershchyna region of Ukraine, has been preserved to the present day. This example of landscape art is part of the “Hetman’s Capital” National Historical and Cultural Reserve. It was founded in the 17th century by Vasyl Kochubei, the general judge of the Hetmanate, in a natural oak grove.

slideshow

In the mid-18th century, Lazar Hloba, a Zaporizhian kozak leader, established three other gardens, as well as four mills, on the right bank of the Dnipro River and on Monastyrskyi Island. Today this is in the centre of the city of Dnipro, and one of the parks established by Hloba bears his name.

Unfortunately, many models from this period have vanished from Ukrainian landscapes. For instance, in the 1830s, there was a large English-style park near the Vyshnivets Palace in Volyn, the former residence of Mykhailo Servatsia, the last representative of the ancient Ukrainian Vyshnevetskyi family. The garden, like the palace complex, was destroyed and redeveloped several times.

During the Russian Empire

After the Russian Empire occupied a large part of Ukraine, Ukrainian peasants again found themselves in a position of serfdom. At the same time, even bigger landowners appeared, furnishing their manors and palaces with decorative plants.

Thousands of recreational gardens and forest parks sprang up at the end of the 18th and during the 19th centuries. The most ambitious and notable parks from that period are the Sofiivka, Oleksandriia, and Trostianets arboretums.

slideshow

The Sofiivka Arboretum, located on the banks of the Kamianka River in the northern part of the city of Uman in the Dnipro region, combines picturesque landscapes with age-old trees, lakes, waterfalls, grottoes, and sculptures. It was created by Polish magnate Stanisław Potocki in honour of his wife Zofia. It is recognised as a masterpiece of world landscape art of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Olexandriia Dendrological Park is located just north of the Ros River on the southwestern outskirts of Bila Tserkva in the Naddniprianshchyna region. It was founded on the site of a former natural oak forest by landowner Count Ksawery Branitski, who named it after his wife Alexandra. The park is mainly composed of a natural forest-steppe landscape, but it also has clearings, meadows, and bodies of water. Its natural landscapes are complemented by diverse architectural structures, including pavilions, gazebos, and bridges.

Oleksandriia. Photo: Pavlo Pashko.

Trostianets Dendrological Park, located in the village of the same name in Sivershchyna, is one of the best-preserved landowner parks in Ukraine. This area was owned by the family of Ivan Skoropadskyi, a philanthropist, prominent Ukrainian colonel, and grandfather of Ukraine’s last Hetman. The park’s territory was artificially rearranged from flat terrain into a more varied landscape. In addition to shaping the territory, pathways were laid out, and rest spots were created with benches and gazebos. The park was decorated with sculptures and bridges.

“Polovetska baba” statue in Trostianets Park. Photo: Mariia Petrenko

Practical experience and knowledge from the history of Ukrainian horticulture were collected and published for the first time in 1837, in a book titled Detailed Instruction, compiled by the head of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra. The author lived in the Kyiv Pechersk-Lavra monastery, talked with the monk in charge of gardening, and experienced monastic life.

During the USSR

In the 20th century, the Soviet occupation authorities brought major changes to Ukrainian lands, particularly through industrialisation and collectivisation. This significantly affected traditional horticulture. After 1917, almost all mansions in Ukraine were robbed and desecrated, and the nearest orchards and parks became abandoned or assigned to local state farms, boarding schools, vocational schools, or other organisations. Due to these practices and other factors, including the dispossession of landowners and the transition from a rural to a more urban lifestyle, the Soviet Union disrupted the historical continuity of Ukrainian horticulture.

The Holodomor, triggered by the occupation authorities in 1932–1933, killed millions of agricultural culture-bearers in various regions of Ukraine. Daily slave labour on collective farms (kolhosps) and the loss of prestige of rural life also discouraged people from cultivating their orchards and gardens. In some places, entire areas lost these traditions.

Levko Symyrenko. Photo source: agroelita.info.

Life could be dangerous for scientists and crop breeders during the Soviet occupation. In 1920, the life of Ukrainian pomologist Levko Symyrenko was cut short by unknown individuals (although most researchers believe the culprits were Chekists or employees of the Soviet secret police). Such acts of violence became part of the repression that the Soviet authorities carried out against the Ukrainian intelligentsia. During his lifetime, Symyrenko created one of the biggest nurseries in Europe, where hundreds of apple, pear, cherry, plum, and other fruit trees were grown. He bred new varieties of fruit, such as the famous “Renet Symyrenko” apple, named in honour of his father.

Pomology

The science of growing fruit and berry plants; a branch of botany.In the Soviet period, artistic horticulture was considered a relic of bourgeois culture and replaced by a simplified “proletarian culture”. Instead of artistic landscaping and parks, many simple green spaces and forests were created in cities and villages.

The shortsighted Soviet tax policies led to the massive destruction of gardens and orchards. People either destroyed them themselves to avoid punishment or witnessed their destruction by state forces. For example, according to a 1948 decree, citizens with who owned plots of land had to pay income tax on crops and perennial plants in addition to land rent. Most peasants could not afford the taxes, which drove them to extreme measures, such as slaughtering livestock, reducing the area of crops, cutting down fruit trees, and uprooting bushes. Some attempted to secretly transplant a few bushes to the forest so they could grow some berries for their children.

Ukrainian literary scholar and writer Zoia Zhuk shared her family’s story of surviving those times. She explains that all the fruit trees and berry bushes in their orchard were cut down, leaving only an almost-barren pear tree, which saved her family during the Holodomor. In 1954, after Stalin’s death and the relaxation of the law, Zoia’s grandfather began restoring his property and planted a large orchard.

“To plant an orchard of apple and pear trees, my grandfather visited all the nearby villages searching for cuttings,” writes Zoia, “because only a few fruit trees had survived. The toughest part was restoring the population of apricots and walnuts — my grandfather’s younger brothers, who were serving in the military, sent him seeds from the Caucasus.”

Another factor that significantly influenced the landscapes of some Ukrainian regions during the Soviet era was the construction of large-scale infrastructure projects, such as hydroelectric power plants. Projects like the Kakhovka, Kremenchuk, Kaniv, Dnister, and other hydroelectric power plants have had tangible consequences for Ukrainians. To create immense reservoirs, the Soviet authorities flooded thousands of hectares of arable land, meadows, and pastures as well as hundreds of villages, along with their gardens and orchards. People lost not only their houses but also the fertile household plots on which they grew vital crops. Many were forced to demolish their houses and cut down their orchards to prevent materials and trees from clogging the dams.

Signs with the names of flooded villages were installed during the “Roaring Dnipro” swim in the Kaniv Reservoir. Photo: Yurii Stefaniak

Overall, due to the Russian and Soviet policies of exploitation, short-sighted experiments, terror, and attempts to exterminate or fully control entire segments of the population who sought to live off the results of their labour, Ukrainian horticulture and viticulture have been altered beyond recognition. This is just one of many areas in which Ukrainians experience a lasting, detrimental colonial influence: unfortunately, there are numerous industries in which Ukraine cannot boast of a long and well-preserved tradition. Russia continues to capture Ukrainian territories and destroy all life wherever it can reach even today. At the same time, since Ukraine’s independence, Ukrainian winemaking has seen a rebirth and is opening itself up to the world. Ukrainian farmers are displaying remarkable resilience in tough conditions and, since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, Ukrainians have been called on to grow “orchards of victory”, since everything always grows and blooms on the fertile Ukrainian land, as long as it is cultivated by free people.

Фото: Катя Акварельна.