In 2022, Ukraïner’s “Listen to the voice of Mariupol” series was released. It features the stories of people who managed to escape the city after it was occupied by Russian forces. In February 2024, with Mariupol still under Russian control, we caught up with the participants of this project. They shared how their lives have changed in the two years since the start of the full-scale invasion. This article follows up with Maria Kutnyakova, who discusses her life in Lithuania, the impact of trauma, and her longing for Mariupol.

Before Russia’s full-scale invasion, Maria was actively involved in developing Mariupol’s local cultural scene. She was an actress in the “Teatromania” Mariupol Folk Theatre for six years and also worked in the “Vezha” cultural and tourist centre. She conducted historical tours of the city where four generations of her family have lived.

Now Maria works as a freelancer and supports projects in Ukraine and Lithuania. She is also a communications officer for Shtuka, a Ukrainian non-profit. Before the full-scale invasion, Shtuka was engaged in educational and cultural projects in Donetsk, Slobozhanshchyna, and Pryazovia. Then it began delivering humanitarian and military aid to regions heavily affected by the full-scale war until some of them fell under occupation. Today, the Shtuka team plans to gradually return to championing cultural and educational projects.

Maria, along with her mother, sister, and cat, remained in occupied Mariupol until the end of March 2022. Her uncle stayed several months longer because of the constant shelling near the Azovstal steel plant. On 16 March, while Maria was visiting her uncle, Russian troops bombed the drama theatre where they were hiding. Fortunately, Maria was able to locate her surviving relatives in the theatre’s bomb shelters. This was when she decided to leave the city as soon as possible. The next day she and her family walked to the village of Melekine, about 20 kilometres from Mariupol. After a 12-day journey to Lviv, they settled in the Lviv Puppet Theatre, which had been transformed into a temporary home for displaced persons. At that time, many theatres far from the front line had turned into humanitarian aid centres.

Moving to Lithuania

Maria’s family believed that Lviv would be their final destination after fleeing Mariupol. They began searching for their own place to stay to avoid relying on their friends all the time. However, they were unable to find an apartment. In the middle of spring 2022, displaced persons from the frontline and near-frontline regions were arriving constantly, narrowing the options. Also, not many apartment owners were willing to accommodate tenants with a cat.

At the Lviv Puppet Theatre, Maria ended up meeting a volunteer from Lithuania named Žilvinas Sviatojas. He was transporting aid to Ukrainian civilians and soldiers. Žilvinas invited Maria and her family to move to his place in Vilnius for a few months to recover and then, if needed, return to Ukraine. Maria agreed. The fact that Lithuania provided free medications was an additional draw: Maria’s older sister required treatment for a disability.

“We stayed with this volunteer, immediately found an apartment, and are now renting. I work online in Ukraine as a freelancer. We get this medical support because [my family members] are vulnerable members of the population. I calculated how much it would cost me in Ukraine and decided in that moment that I would stay in Lithuania as long as we have this medical support.”

While preparing documents for her mother’s surgery and rehabilitation, Maria and her family were also attempting to evacuate her uncle from Mariupol. He lived near Azovstal, where the fighting was fierce. It was impossible to reach this part of the city in April 2022. Maria shares that for a month and a half, they had no idea whether her uncle was alive, and for another month and a half, they tried to evacuate him. He was only able to leave for Lithuania, via the territory of the Russian Federation, in June of that year. The occupation and this long journey harmed his health, and he developed heart and lung issues. Lithuanian doctors decided to operate on him. He first spent about a year restoring his weight and water balance, and then he had a successful operation. However, a few days later, a blood clot broke off in his body.

“We had a cremation here. When Mariupol is de-occupied, we want to bury [my uncle] with our relatives in the cemetery, bringing him back home. I always state that the Russians killed him.”

Maria has noticed that it is not unusual for Ukrainians — particularly those who have lived under occupation — to experience a worsening of chronic conditions or unexpected bone fractures. Constant stress, starvation, hypothermia, and a lack of drinking water have drained their bodies. In addition to her uncle, Maria’s mother also required surgery after falling in the middle of the street and breaking her hip in her second week in Vilnius. There were numerous Ukrainians suffering from similar injuries at the hospital where she recovered.

“Many residents of Mariupol, even younger ones, are dying from chronic conditions they developed during the blockade of the city. I have several 50-year-old friends who got pneumonia from being in the basement. They were unable to get it treated and died in Ukraine or elsewhere in Europe as a result.”

Photo from Maria Kutniakova's personal archive.

After living under occupation, Maria developed sleep and concentration problems. She only works part-time because an 8-hour schedule would be too much for her. She has also sought psychological help. Despite experiencing times when she feels like doing nothing at all, Maria is learning to care for herself and her loved ones. She shares that the most painful emotions have passed and she is ready to return to hating Russians. In addition to her and her family’s health issues, airplanes also remind Maria of her experiences in Mariupol. Vilnius Airport is located in the city centre, and it took some time for her to accept that there would be no Russian military planes there, and that if there were, they would be destroyed by air defense.

Photo from Maria Kutniakova's personal archive.

“NATO fighter jets monitor the borders from time to time. I understand that they’re far away, but they fly at 4 a.m., and the whole city can hear them. Sometimes I wake up from the sound and see someone turn on the lights in the house across the street, so I know I’m not alone.”

Adapting to Vilnius

In the nearly two years that Maria has lived in Vilnius, she can hardly recall a place where she hasn’t encountered someone from Ukraine, be it a coffee shop, a post office, or a supermarket. In December 2023, Lithuania’s Department of Migration stated that Ukrainians are currently the largest national community in Lithuania. As many as 85 thousand are living there. Maria jokes that it is becoming increasingly challenging to find someone to practice Lithuanian with due to the abundance of Ukrainian speakers.

“Sometimes I feel like I’m living in the ‘Vilnius region’ of Ukraine. I read Ukrainian news, work with Ukrainians, and communicate with Ukrainians here. I often hear stories about Ukrainians who have forgotten their homeland, but that’s not the case here. Sometimes, when I’m surrounded by Ukrainians, I try to discuss Lithuanian news, such as the celebration of Vilnius Day. However, they seem more interested in discussing how the World Economic Forum meeting will impact Ukraine. They aren’t interested in talking about Vilnius’s birthday.”

Photo from Maria Kutniakova's personal archive.

Maria notes that the close communication between Ukrainians and Lithuanians following Russia’s full-scale invasion helps eliminate mutual prejudices imposed by the aggressor country itself.

“For example, after coming here, I realized that I had a somewhat Soviet-era perception of Lithuania. Lithuanians also had their own preconceived notions about Ukrainians. So when we met, they were also a bit shocked, pleasantly surprised by us. And so they had a question for us too: who are you, and what’s your identity?”

Maria believes that understanding the countries’ shared past is key to the populations better understanding each other. For instance, the territories of Ukraine and Lithuania were once part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. They later became part of the Russian Empire and the USSR. Both countries resisted the communist occupation regime and eventually gained independence before the collapse of the Soviet Union, and they both subsequently went through a process of decolonization.

Maria also believes that folklore plays a large role in bringing people together. “My mother has been lecturing on Ukrainian culture and folklore for a year now, just as she did in Mariupol. This topic is significant because, after 24 February 2022, many Ukrainians realized that they lacked knowledge about their own country. Lithuanians know about their own culture and history, and they’re interested in learning more about Ukraine and Ukrainians.”

Photo from Maria Kutniakova's personal archive.

Attendees can learn about Ukrainian folklore from Maria’s mother in two languages: she speaks Ukrainian, and an interpreter translates into Lithuanian. There are even people of other nationalities who are eager to listen to the lectures. Maria recalls one particular guest who left a big impression.

Photo from Maria Kutniakova's personal archive.

“It was the last lecture, and a Chinese man in an embroidered shirt came and spoke in broken Ukrainian. And we were like: ‘Oh my God!’. And he said: ‘I just decided to study the Ukrainian language, Ukrainian culture, because it’s such an inspiring country, such an inspiring nation.’”

Maria’s cat has also been socializing more with the locals. When Maria left Mariupol, her cat lost around a kilogram of weight, which was noticeable due to her build. However, now that the environment is safer and calmer, the family’s four-legged friend has started to live her best life, according to Maria.

“A lot of cats hang out at the entrance of our building. Our cat walks by the entrance and meows at the other cats through the door. We also have open-air balconies, and our neighbour’s cat likes to sit on their balcony. When the weather is warm, our cat and the neighbour’s cat sometimes sit on their balconies opposite one another. She has Lithuanian friends now.”

A desire to return home

Although Maria was able to find housing, work, and support from both the Ukrainian and Lithuanian communities, she doesn’t plan to stay permanently. She believes she will live in Ukraine, not just travel there on business. Her phone helps keep her connected with her hometown at least a little — she has it set up to show the weather in both Vilnius and Mariupol.

“I can’t get used to the climate [in Vilnius] because it’s colder, wetter, and less sunny. I keep thinking about how it is in Mariupol. I’ll see that it’s above freezing in Mariupol and below freezing in Vilnius, and I’ll think, ‘Fucking Russians.’ I miss the sea very much. I’m one of those people who never leaves the beach in the summer: after work, even if I don’t go swimming, I go to the beach, or I’ll even go before work.”

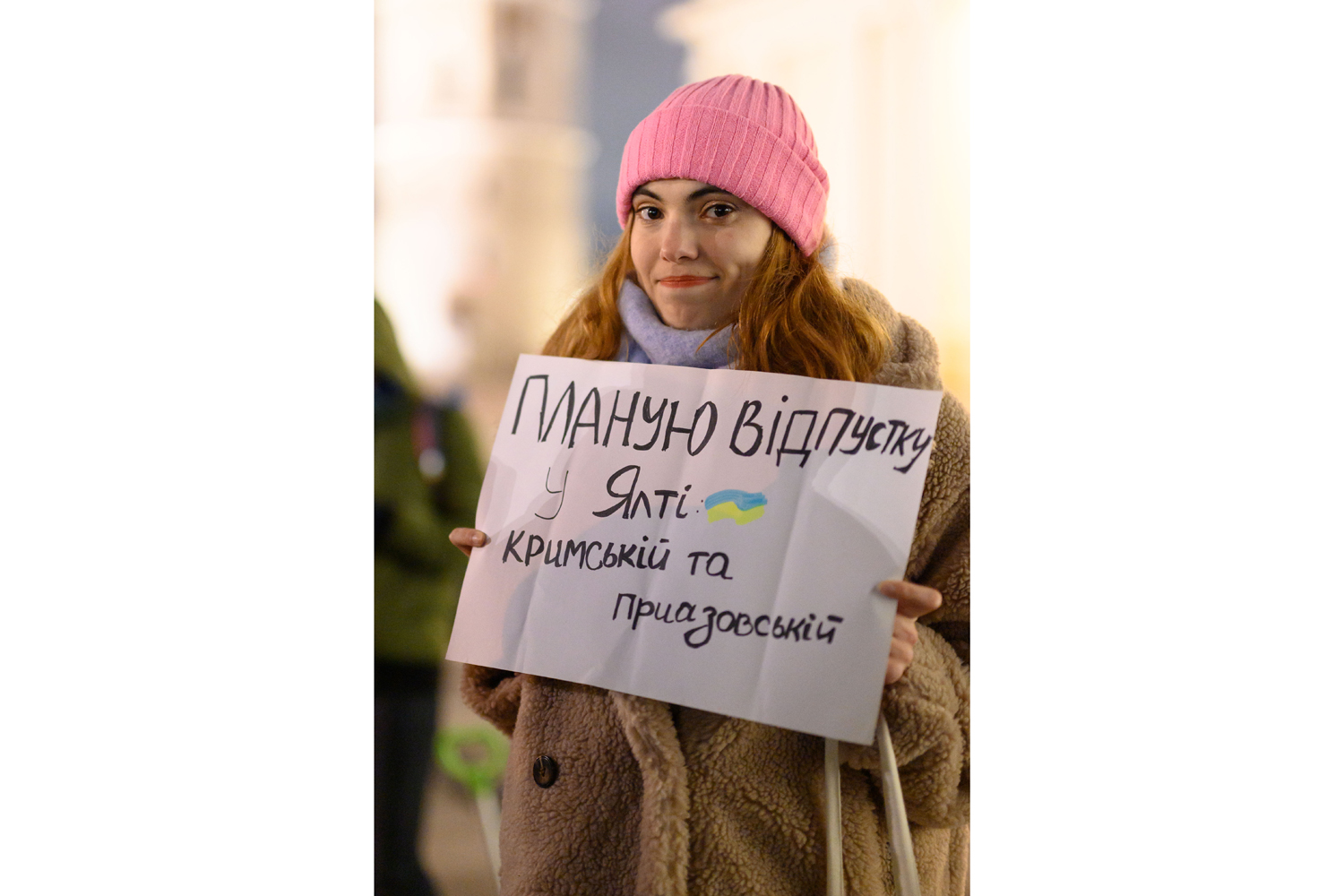

Photo: Dmytro Bartosh.

However, it’s difficult to predict whether Maria will live in Mariupol again. Mentally, she is only able to plan up to three days ahead. It’s more likely that she will be able to visit the city and join volunteer initiatives to rebuild it. Her home was completely destroyed by Russian bombs, and the occupation authorities have been using her mother’s partially intact apartment for their own needs. They do not consider Ukrainian property documents to be valid. Remaining residents have told Maria that construction workers from Tajikistan moved into the high-rise building where her mother lived.

“They took everything from [my mother’s] apartment. Twenty people lived in her two-room apartment without a working sewage system. But the weirdest and most shocking thing was that they started an open fire in the kitchen to cook pilaf in a huge pot.”

Photo from Maria Kutniakova's personal archive.

Maria communicated with some other so-called neighbours personally. One day, a stranger contacted her on Viber and asked for access to her mother’s apartment in Mariupol to fix the gas system. After exchanging a few messages, the woman revealed that she was the wife of a Russian soldier who had been living in their building for several months. She complained that he had to cook in a slow cooker because there was no gas supply in the building.

“Well, I told her: ‘So he can go outside, make a fire, and cook.’”

Maria is no less hurt by the way that Russia portrays Mariupol in the media. It emphasises the good climate, the sea, and affordable apartments while deliberately silencing the real lives of the surviving Ukrainians. And this distorted image of the city isn’t only spreading in Russia: even some Ukrainian citizens are not fully aware of the brutality of the occupation.

“On New Year’s Eve in Vilnius, many people from the unoccupied territories went to Ukraine to visit their families. Some of them asked me if I was also planning to go to Ukraine for the New Year. I replied: ‘I’m from Mariupol, where should I go?’”

Photo from Maria Kutniakova's personal archive.

Maria feels that global society is becoming more and more accustomed to the full-scale war and is less ready to show support and empathy for Ukrainian refugees. She assumes that, as a result, some states will push refugees from Ukraine to return home. However, some Ukrainians are already choosing to return home to join the army, volunteer, rebuild the country, support its economy from within, and so on.

“I think of my grandmother all the time. She was also evacuated during the Second World War and lived outside of Ukraine for several years. I tell myself that I will have a similar experience of living in Europe, in beautiful Vilnius, that I will cherish with warmth and love. However, I am fully aware that after living in Europe, I will have a greater appreciation for Ukraine, recognizing it as the best country in the world with the best people, cuisine, service sector, and everything else.”