Irpin is one of the Ukrainian cities where reconstruction efforts have expanded into an extensive campaign involving numerous stakeholders. Residents of apartment buildings independently repair roofs damaged by shelling and replace windows in their homes. Lithuanian partners are engaged in restoring socially important facilities, including a local kindergarten. The Ukrainian authorities have launched the construction of a vital bridge next to the one that was blown up. Finally, Ukrainian experts have created a comprehensive digital platform where affected communities and interested donors can find each other and develop transparent cooperation.

Located in the suburbs of Kyiv, Irpin was partially occupied at the onset of the full-scale Russian invasion and turned into a grey zone where fighting occurred. Many residents evacuated in the early days, with some passing under the destroyed bridge over the Irpin River. However, many stayed in the city, particularly in the occupied areas, deprived of electricity, communication, and water, forced to hide in basements as the occupiers looted their apartments. After Irpin was liberated on 28 March 2022, numerous media outlets and foreign delegations started visiting the city to witness firsthand the death and destruction left behind by the Russian world. During the first month of the all-out war, 70% of city infrastructure was damaged.

So far, the reconstruction of Irpin has been localised: residents take care of their homes, while foreign partners implement projects that mainly concern social infrastructure. However, compared to the spring of 2022, significant progress has been achieved in adopting a more comprehensive approach to recovery. In the new material of the multimedia project “Restoration of Cities“, we feature the governmental digital platform for raising funds for reconstruction – DREAM, as well as the efforts of the State Agency for Reconstruction and Development of Infrastructure, in particular, their input in the restoration and memorialisation of the Irpin bridge. Similarly, we will explore the case of the Ruta kindergarten, which Lithuania has committed to restoring, and share the vision of Irpin resident architect Oleh Hrechukh on the further development of his city.

Recovery Agency

At the beginning of 2023, Ukraine established the State Agency for Infrastructure Restoration and Development, based on the State Agency for Infrastructure Projects and the State Road Agency. The body is subordinated to the Ministry of Community, Territorial and Infrastructure Development of Ukraine. The head of the agency, Mustafa Nayyem (Mustafa Nayyem vacated the post in June 2024 – ed.), explains that the ministry develops a recovery strategy while the agency ensures its implementation. The agency is currently undertaking plenty of crucial tasks, including maintaining bridges and roads of national significance; constructing mechanical protection for energy facilities against debris; providing water supply in Podniprovia and Zaporizhzhia; developing infrastructure of checkpoints on the western border (a vital artery for delivering goods, such as weapons); rebuilding social infrastructure; and restoring housing, particularly in Yahidne, Sivershchyna, Posad-Pokrovskyi, Prychornomoria, Irpin, and Polissia.

Mustafa illustrates the priority of the chosen directions using the example of a checkpoint; before the full-scale war, ports were open, and planes were operating, so the load on roads and railways was much lighter.

“Currently, 80% of everything that leaves the country is transported by road.”

Mustafa says many similar challenges arise due to the all-out invasion: the country has never faced such extensive destruction, and major projects like the 140-kilometre water pipeline were implemented long ago, some dating back to the Soviet era. Likewise, there is a need to establish the restoration and construction of housing. The state currently lacks appropriate mechanisms, as the real estate market has been privatised.

“Currently, we are preparing our recovery vehicle to the maximum extent possible. After the war it will handle modernisation, introducing new standards, etc. One of our missions is being the most stable, reliable partner trusted by all stakeholders in the construction industry – donors, state authorities, local self-governments, and most importantly, citizens. Therefore, reputation is crucial for us.”

In February 2024, the agency presented the inaugural Recovery Guide, detailing the sequence of actions and the documents required for recovery efforts. It can be used, in particular, by local governments.

One of the agency’s key messages, both domestically and internationally, is the urgency of completing recovery now, during the war. Mustafa emphasises that it concerns the infrastructure that ensures the country’s ability to live and defend itself.

“So far, we have been focused on the survival stage rather than recovery. The country must endure to the end of this war and prevail. Then, we will undertake restoration, development, and so forth. At this stage, with limited human, financial, and even psychological resources, [we] have to do everything possible to ensure that people can live with as much comfort as they can [in these circumstances].”

Mustafa believes that the public should be engaged in discussing nearly all projects funded by the public, except for military or other closed facilities. For this purpose, the agency employs various tools, such as the Integrity Council, which comprises civil society representatives.

“Since we operate locally, i.e., in the regions, and our primary client is a resident, […] we always conduct public hearings. There is a well-defined legal procedure for how they should be conducted – people participate by voting.”

This mechanism was implemented during the discussion of the design code for Yahidne village and when deciding whether a school, kindergarten, library, and stadium should be combined into one complex in Posad Pokrovskyi. Mustafa says officials in different regions sometimes treat this procedure as a formality. Still, he believes ensuring the legitimacy of the decision and people’s trust in the authorities is crucial.

“I think that trust is the main asset that will allow our agency and the country to attract more resources and advance faster in the future.”

Irpin Bridge

In today’s war, many key events are associated with reporters’ photos. One of ігср is the destruction of the bridge over the Irpin River on 25 February 2022. It halted the occupiers’ advance towards Kyiv but also trapped the residents of Bucha, Vorzel, and Hostomel, where the intense fighting was unfolding. The footage of civilians evacuating on the planks under the ruins of the bridge is shocking.

“Hundreds of people were standing under the bridge, with transportation being blown up. Indeed, it was one of the symbols of those days, and the start of the [full-scale] war, when people were deprived of the opportunity to leave, yet it was the only way to stop the occupiers,” Mustafa says.

After the Ukrainian defenders forced the invaders out of Kyiv, a small temporary causeway was promptly constructed next to the destroyed bridge, enabling traffic to transport weapons, medicine, and food and facilitating the return of residents. Simultaneously, the decision was made to build a full-fledged bridge near the destroyed part, similar to the one that existed before the destruction. Mustafa highlights the promptness of actions, which is unusual for publicly funded projects.

“Probably in peaceful times, such decisions would have taken much longer.”

He explains the practicality of restoring the bridge for the community’s convenience (the narrow causeway caused constant traffic jams) and as a vital transport artery, facilitating warfare.

“We must understand that in wartime, logistics serves as a part of the military infrastructure, making fighting possible. Talking of bridges, defence highways, fortifications, and so forth, they do not oppose the war.”

In addition to practicality, this construction project bears a symbolic meaning.

“For us, it serves as a vivid example that life must go on despite the war. People can’t give up on life because they still have tasks, including military duties, so they must continue fighting and endure through this time. Thus, despite the war, the recovery effort is underway”, states Mustafa.

In addition, Mustafa’s team initiated the construction of a memorial at the site of the destroyed bridge. This proposal was approved during the public hearings. Plans have also been made to create a park, and the drafts are already prepared for implementation once the war is over.

“The idea consists of preserving the bridge exactly as it was after the explosion. That is, even the vehicles that were blown up there will be kept in this form; nothing will be restored in the destroyed section.”

Mustafa adds that he realises that this picture may be painful for people who drive by every day. Still, it is primarily about preserving the memory for future generations of Ukrainians.

“I do hope that our children and grandchildren will remember this, and remember the cost, and more importantly, will not allow the return of the same traditions when Ukraine was imbued with Russian influence at all levels. This memorial should stand as a monument preventing that from happening again.”

The restored bridge was opened on the Day of Dignity and Freedom in 2023.

“By the way, this is symbolic. We opened it to traffic on November 21, the day the Revolution of Dignity began. We didn’t do it intentionally; it happened due to the circumstances.”

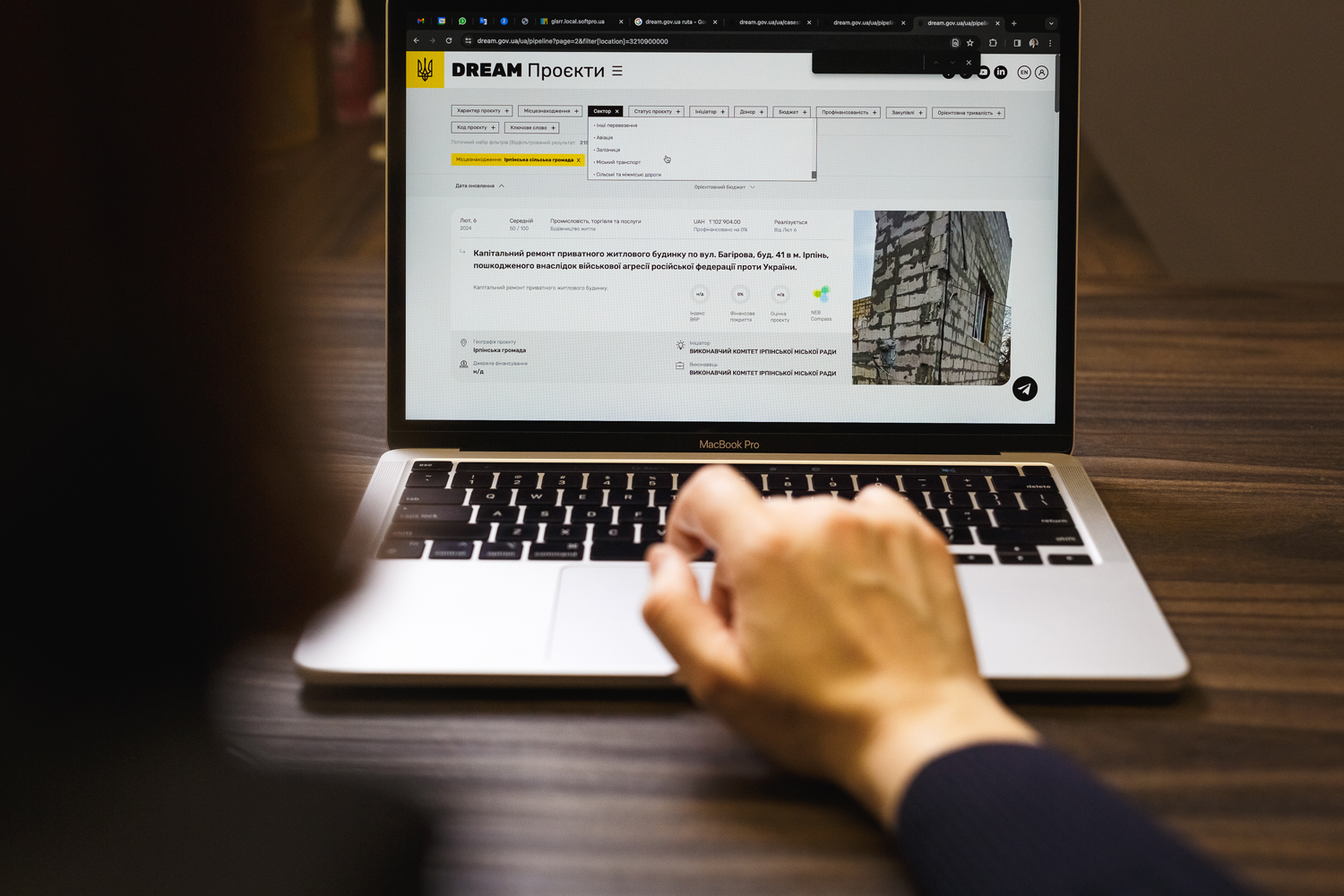

DREAM: digitalisation and transparency of recovery projects

Oleksandra Azarkhina was Deputy Minister of Communities, Territories and Infrastructure Development of Ukraine from December 2022 to May 2024. She recalls that at the onset of the full-scale war, following the initial de-occupations and counter-offensives, the term “rapid recovery” was actively circulating. The idea was that as long as attacks continued, authorities would focus on repairing, and once the occupiers were driven out, they would switch to rebuilding. However, when partners asked about a recovery strategy, the ministry lacked objective data on the scale of destruction, failing to provide the foundation for its development. This realisation led to the understanding that data had to be continually collected and updated as new destruction occurred.

“If a strategy does not have proper data, it is anything but a competent strategy,” she says.

In 2023, Oleksandra travelled to Japan, a country that has developed advanced recovery mechanisms due to its location, making it vulnerable to tsunamis and earthquakes.

“They even have a special form of contract: before the destruction even occurs, they have already selected approximate contracts that have to start work immediately so no time is wasted because they still need to rebuild. They revealed to us that recovery priorities [include ensuring] the psychological stability of the population and creating workplaces. The psychological stability of the population is linked to whether a person has a job. After that comes social infrastructure and the rest; this was also a significant rethinking for us.”

The Japanese approach highlights that recovery is a complex process in which enhancing the economy is as crucial for cities as rebuilding their walls. If jobs are available, people return, pay taxes, and enable communities to have sustainable budgets.

The DREAM system was invented in the spring of 2022 following the first de-occupation of settlements during the full-scale war. It became clear that many projects needed to be controlled, deadlines, and quality monitored so that all procurements were transparent, fostering trust in Ukraine among its partners.

“The superpower of this system stems from the fact that it was born by the equal efforts of the state, the public, and international partners,” claims Oleksandra.

It was implemented based on previous experience, including project management from the governmental Big Construction programme (E-Road online platform) and developing the ProZorro* procurement system. It also utilised existing registers and ecosystems like Diia**, the Unified State Electronic System in Construction, the Register of Damaged and Destroyed Property, and the Unified Web Portal for the Use of Public Funds Spending.

“DREAM” is an acronym for Digital Restoration Ecosystem for Accountable Management.

ProZorro

Ukrainian public electronic procurement platform that was implemented in 2016 to ensure open access to public procurement (tenders), minimising corruption risks“This system is the only chance [for] us as citizens of Ukraine, [for] our partners, to get full transparency and accountability in the reconstruction process. If our team hadn’t developed this system, someone in Ukraine would have come up with it anyway. As a state, we have already come a long way with Prozorro and Diia. And we already have digitalisation in our state-building code.”

To implement the system, its creators established a project office, which operates with the support of British and German partners. The Ministry provides a legal framework for operation, ensuring not only the technical implementation of this system but also its overall efficiency.

“Not only I but also other deputies and the Deputy Prime Minister himself oversee this within the Ministry. For [the system] to work properly from a digital standpoint, it requires a proper legislative basis and proper procedures to ensure that it is not just for display, but really aligned with our reality.”

Diia

Ukrainian e-governance ecosystem allowing citizens to utilise 14 types of digital documents (such as ID cards, foreign passports, and driver's licenses) instead of physical ones and access over 120 governmental services online. Since its introduction in 2020, this service is currently used by more than 20 million Ukrainian citizens.

DREAM was publicly presented in June 2023 at a conference in London dedicated to the reconstruction of Ukraine. In 2024, the team is preparing for a similar conference in Berlin, where they will talk about the updates that have been implemented over the year (the conference was held in June of 2024 – ed.).

One example of restoration is the Ruta kindergarten in Irpin, which we will detail below. The DREAM website features comprehensive context and all project-related information, including its budget details (procurement, operating costs, sources of income), reconstruction stages, photos, and more.

Currently, the main users of DREAM are the communities affected by the shelling and donors interested in investing in the reconstruction. However, Oleksandra’s team plans to expand this circle over time, engaging NGOs and businesses. She notes that the restoration agency is a major client in this process, as it focuses on flagship state projects that specific communities cannot be implemented relying on their own resources.

Presently, the use of DREAM for hromadas* is optional rather than obligatory, but Oleksandra claims that the team is working on ensuring that in the future all major investments in hromadas go through the system, securing transparency of the process.

“When I, [ nominally as] a community leader, create a project, I begin by defining the task. For example if my school was bombed, the system itself asks, “Are you sure you need to rebuild this particular school in its original format? Or maybe you can buy buses and provide transportation for the children to the neighbouring village? Or perhaps build a new modular one with less space but a good shelter?” In other words, the system enables us to develop a better solution right from the start,” she explains.

Oleksandra emphasises that DREAM does not seek to centralise recovery, but rather support the ongoing process. Consolidating everything in one system prevents situations like the one in Borodianka, when six donors were simultaneously ready to restore one kindergarten, having to put in extra time to sort out this issue.

“I think we are all fortunate that Ukraine’s recovery is a highly decentralised process. On the one hand, we have a lot of real beneficiaries and recipients: communities, schools, utilities, partners, and donors. These can [include] a development agency, a private investor, or an international financial organisation from one state. And all these organisations interact and have [their own] priorities.”

The prioritisation tool works as follows: if a donor is interested in, for example, inclusive spaces for veterans, green technologies, or education within the context of recovery, the DREAM system assists him with selecting suitable projects. Likewise, the system affects communities, encouraging their responsible attitude to recovery and working transparently to attract more sponsors in the future. Additionally, municipalities can upload their development strategy to the system, ensuring that reconstruction occurs systematically rather than pointwise.

The ministry prioritises cybersecurity, avoids publishing sensitive information about strategic facility destruction, and uses cloud storage, among other measures. Oleksandra says that when Russian hackers attacked the ministry’s website, her team laughed at this episode, proving that Russians don’t grasp a notion of a truly decentralised system. The ministry site mainly serves as an information service rather than a source of information that could be potentially valuable to the enemy.

“We say that it is similar to how the Russians bomb’ decision-making centres’. However, in our country, every citizen is at the centre of decision-making.”

"decision-making centres"

During Russian strikes on civilian infrastructure – schools, markets, residential buildings, post offices, etc. – its propaganda media often present it as an achievement, claiming a successful attack on the enemy decision-making centres.According to Oleksandra, the team is trying to make the system user-friendly for everyone, including donors, who can create their own page in the system where their projects will be integrated.

“The biggest challenge is for our partners to demonstrate the same transparency and accountability that Ukraine has shown. Not everyone is ready for this. For them, in many ways, it’s like, ‘So, now we have to reform ourselves?’ And Lithuania is leading the way in this regard.”

In addition, DREAM serves as an informational source for investigative journalists and activists monitoring the recovery process. Oleksandra jokingly says that if there is corruption, it will be noticed online – highlighting that system transparency functions as a kind of safeguard. Ukraine’s international partners also realise this.

“The four largest international financial institutions – the World Bank, the European Investment Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and the Council of Europe Development Bank – have signed a memorandum in which they said, ‘We are using DREAM as the ground for managing reconstruction investments in Ukraine.’ It means that faith and trust in the system are already very high,” she says.

Oleksandra views DREAM as a promising development not only for Ukraine but for other countries as well.

“I want my parents to be able to access the system while walking in the Bucha community and see unfinished construction sites. [They should be able to monitor] where the construction is [happening and] where it is not, whether there is a contractor or not, whether money has been paid to the contractors for works but the street lights have not been installed, although it is reported that they have been. In fact, this is a huge corruption prevention mechanism. We can already take pride in this as a state because [even] the most developed countries do not have something like this yet. We will teach them later.”

Kindergarten “Ruta”: real restoration — when children grow up in the city

Kseniia Katrych is the director of the Ruta kindergarten in Irpin. At the onset of the full-scale war, residents from neighbouring houses took refuge in the kindergarten basement. On 6 March 2022, the Russian army shelled the facility, causing a fire that destroyed the roof and part of the building, along with furniture and equipment. The damage inflicted by this and subsequent shelling and rainfall was so extensive that mere repair was unsustainable, requiring extensive restoration. In August 2022, the Lithuanian government undertook the project. The renovated facility opened its doors on 24 August 2023. As a gesture of gratitude to Lithuanians, the kindergarten was renamed Ruta, a plant symbolic of Lithuania and with its name resonating in both Lithuanian and Ukrainian languages.

Before reconstruction, the facility was named “Joy” and stood as one of the largest in the city, accommodating approximately 400 children in 12 groups, including four specialised groups for children with autism, Down syndrome, and mental disorders. The kindergarten employed about 70 staff members. Originally a two-story building, it has expanded to three floors after the renovation. This includes adding more classrooms, specifically for hosting classes with a speech pathologist, defectologist, a psychologist, and teacher self-training. The canteen and laundry room were redesigned, and most importantly, the basement was expanded and modified as a shelter, equipped with six exits, heating, ventilation, and toilets. It now also features rugs for games and furniture.

“Apart from the low ceiling, everything is arranged the same as in the group rooms,” says Kseniia.

If the air raid alarm goes off during lunch, the children can eat in a shelter. The shelter also has three bedrooms available.

“In agreement with their parents, two- and three-year-olds sleep in the shelter. They have lunch, go downstairs in an organised manner, and if they want to, change into their pyjamas. And the kids spend their nap time in the shelter. It’s very convenient, dark and quiet. The air quality is good, and the temperature is suitable for sleeping. They’re used to it, so they don’t feel stressed. Most importantly, you don’t need to pick up this sleepy baby while an alarm is on and carry them downstairs in your arms. So we are very grateful to have this opportunity.”

After reopening in October 2023, “Ruta” recruited eight out of thirteen groups. Kseniia says that many children who attended the kindergarten before the destruction returned.

“Of course, they are aware of their kindergarten’s history, but children have a different way of coping. They live their preschool childhood as they should: with joy, new emotions, and friends they have had since the pre-war period (before the full-scale war—ed.). They brought all their best and ignited the spark of renewal in this kindergarten.”

As of early spring 2024, the kindergarten accommodates 230 children across ten groups. An online queue is operating, gradually filling up the remaining groups.

“Educators call [the children’s parents]: ‘Hello, we invite you to kindergarten.’ This joy is indescribable. They (parents – ed.) are waiting, which means great demand exists. We still have many children [on the waiting list].”

“Educators call [the children’s parents]: ‘Hello, we invite you to kindergarten.’ This joy is indescribable. They (parents – ed.) are waiting, which means great demand exists. We still have many children [on the waiting list].”

“I had a fulfilling job there. I also worked in a preschool, taught in a foreign language, working with preschool children. There was authority and cooperation; everything was excellent. But my heart was drawn back to our community, our kindergartens. So, our education department offered [me] to lead this project, the new Ruta kindergarten. I had already had the [relevant] experience: I had been working in another kindergarten in our community since 2017.”

Kseniia’s husband has been serving in the Ukrainian Armed Forces since the first days of the full-scale invasion, although he had previously had a successful marketing career.

“In our family, we live by the call of our hearts,” she says.

Kseniia took over as head of the kindergarten in May 2023 when the restoration process was underway. She understands the immense effort required for rebuilding, appreciates Lithuania’s help, and emphasises that real recovery happens only after people return.

“The fact that our partners from other countries provide opportunities is great. But we, Ukrainians, must do everything ourselves.”

Vision of the future of Irpin

Architect Oleh Hrechukh appreciated Irpin’s green and low-rise nature, driving him to buy an apartment there in 2014. Oleh wasn’t in the city in the early spring of 2022, where the heavy fighting occurred. After his return right following Irpin’s de-occupation, he saw that nearly all the windows in his apartment building had been smashed, while the facade, the roof, and even some apartments had been destroyed. Fortunately, the head of the condominium and several residents volunteered to cover the roof with cellophane in March 2022, immediately after the damage occurred, making the building vulnerable to precipitation.

“If you do it quickly, you won’t have to cover the repair of what’s underneath,” says Oleh.

Oleh recalls the city’s view right after the de-occupation: burnt houses and ruins everywhere, interspersed with people cleaning the glass and covering the roofs with oilcloth.

“I just couldn’t pull myself together: how could this happen? [Just] a month ago, this was such a promising European city. […] And then, people are heating food over fire; there’s been no electricity, water, or gas for a month. Hungry dogs are wandering around. Humanitarian aid is being distributed.”

Later, after the Russians were driven out of Kyiv, the residents of the building united to restore it, repairing the roof and facade, removing construction waste, and replacing the parapets. It cost them UAH 100,000 (approximately $3,420 at the moment after Irpin’s de-occupation – ed.), or about UAH 1,000 per apartment (roughly $34 – ed.).

“The residents raised money. In addition, we did some of the work ourselves, without spending money on it.”

After the liberation, Irpin was a city of thousands of broken windows. The Texty media outlet approached Oleh, asking to describe how he replaced his own and share his experience. Oleh encouraged his neighbours in the house chat.

“I said: ‘Look, I changed the windows.’ And they start calling me: “Listen, how did you do it? Can you help us? Because we are abroad – can we give you the keys? Where did you order the double-glazed windows? Is this a problem now? How much does it cost?” My energy motivated three neighbours to change their windows.”

Oleh recalls that replacing double-glazed windows cost UAH 10,000-20,000 (approximately $340-680 after Irpin’s de-occupation) for one apartment. People did not keep receipts, so they did not anticipate compensation (from the government – ed.). However, not everyone could replace their windows immediately; some did so in December 2022. In the spring of 2024, people have already returned, and the entire building is now fully glazed.

As for waiting for government assistance, Oleh believes it is practical to assess the damage first; if it is relatively minor, he recommends beginning restoration independently.

“I’m all for the initiative, for people taking the lead and responsibility. […] Even carrying bricks or helping with dismantling engages you in the work and co-creation, making you realise you are not alone. Obviously, it can be a heavy burden or a heavy blow for one person, but when many people unite to work together, it becomes manageable. And it unites the community, making it stronger and able to address internal challenges.”

Oleh is researching and writing about restoration in Ukraine, with a particular focus on project estimates. He is elaborating on a study of bridge construction in Ukraine, which European partners requested.

“It might seem that war is everywhere, [there is] no money, and nothing is being built. [However] as for bridges, we have active and serious construction. Yet, there is little structured information on the Internet concerning financial flows [related to such projects],” summarises Oleh.

He is aware that certain information should be classified under martial law, yet he believes that the public should be shown how tenders are held. For example, Oleh compares the bridge construction budgets allocated in the EU and Ukraine for projects sharing similar length, width, height, and other parameters. His calculations reveal that construction in Ukraine often incurs higher costs.

Oleh observes that Irpin began to recover immediately after the liberation in the spring of 2022. However, this process lacks a systematic character, and the current master plan continues the Soviet approach.

“There was a spike of enthusiasm but no understanding of how to do it all comprehensively, quickly, with normal sidewalks and infrastructure. In most cases, this is still the case today. There are sporadic efforts, [driven by] the enthusiasm. People simply wanted to live here,” reflects Oleh.

However, the first steps towards a systematic approach have already been taken. Remarkably, the Irpin Investment Council initiated uniting architects, planners, urbanists, designers, engineers, and other specialists from various cities into the Irpin Reconstruction Summit working group. Additionally, in 2022, local authorities established the Irpin Recovery Fund and the Irpin Help information resource, collecting official damage assessments of the social and residential infrastructure, recovery estimates, and data concerning the involvement of international partners in the city’s reconstruction. Notably, prominent architectural firm Gensler is engaged in advancing Irpin’s development strategy.

Oleh emphasises the importance of completing the master plan as a starting point that should precede designing local standout landmarks, like the area’s tallest or broadest structures. Instead, it feels like Irpin is trying to compensate for its provincial status compared to Kyiv, with such isolated achievements. At the same time, it should instead highlight its unique features, distinguishing it from the capital.

“Irpin can offer more of something different that Kyiv can not, and this should become the main feature: yes, we will never become Kyiv, but we do not want to.”

Due to the public transport service connecting to the nearest Kyiv metro station, residents are often stuck in traffic jams trying to leave, prompting Oleh to jokingly compare Irpin to a bedroom community of the capital.

“Irpin has the advantage of pine trees, walking areas, and pedestrian courtyards. But the way the [transport] infrastructure is designed, it just shouts to people: ‘Buy a car!’”.

An integrated approach could also make the city self-sufficient by fostering more workplaces, services, leisure activities, and other conveniences.

“As for cultural facilities, there is no cinema or theatre [in Irpin]. I mean, why would you want to have all of that here? Go to Kyiv. […] The current development pattern of Irpin is buying a plot of land with private houses and repurposing them into multi-story buildings or townhouses. They build and sell them, and new residents move in. But do new jobs, kindergartens, and any infrastructure appear?”

Yet, new services are emerging in response to demand: residents establish private kindergartens, hairdressing salons, massage parlours and more. However, Oleh dreams of a scenario similar to Lviv, where developers operate in a competitive environment, prioritising the quality of playgrounds, the availability of a kindergarten, school, cultural institutions, and convenient transport links nearby, adding value to the apartments.