Russia has been an empire for over 300 years. Formed during the reign of Peter I, it existed until 1917 and then transformed into the neo-empire known as the Soviet Union. After the collapse of the Soviet Union at the beginning of the 1990s, Russia had the opportunity to reframe itself and become a modern European federation. Instead, Russians opted for strong authoritarian rule and imperial nostalgia. This resulted in numerous wars and military conflicts in the Caucasus, Georgia, Syria, and the current Russo-Ukrainian war.

*

Use VPN to view the links to Russian websites in the article.Imperialism of Tsarist Russia

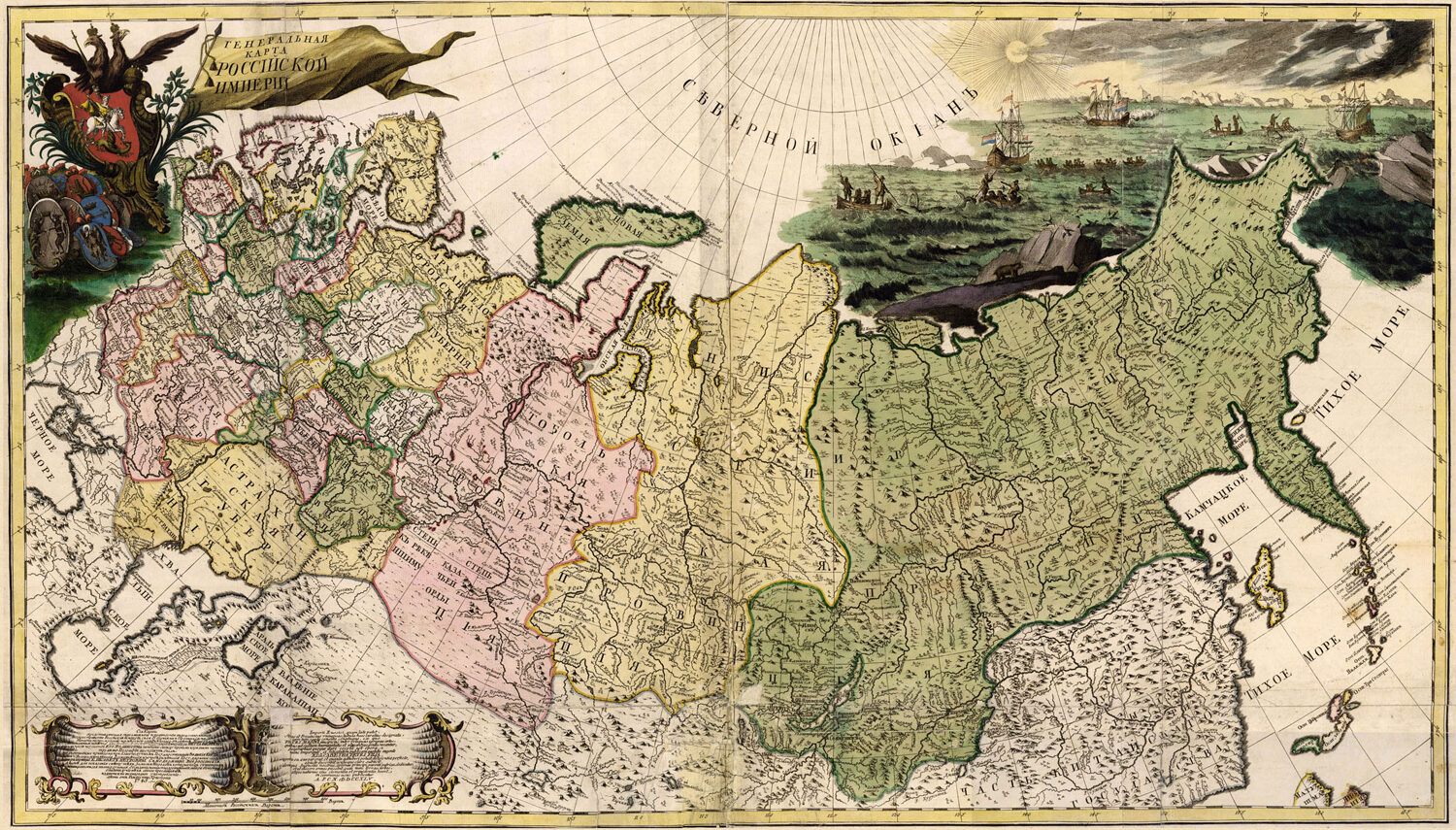

Russian imperialism developed in nearly the same way as in any other European country. The emergence of elites prompted the need for expansion, and inevitably led to wars of aggression to conquer new lands. After all, colonies are the essential feature of imperialism.

A classic colonial empire is a state in which the metropole is not territorially connected to its colonies. Great Britain is the best example of such an empire. The island with its capital in London never had a land border with its colonial territories, which were much larger than the metropole itself. Portugal, Spain, France and the Netherlands also belonged to this category of colonial empires.

Metropole

The centre of an empire that founded or conquered colonies and reigned over them.Russia developed as an empire of national “peripheries” whose colonies are territorially integrated into the metropole. Another example of this kind of empire was Austria-Hungary.

Russian empire-building had its special features. Firstly, the boundaries between ancestral Russian lands and the colonised territories were erased. While the British could not claim that, say, India or Sudan were ancient British territories, Russia claimed “historical rights” to territories that were never ethnically Russian in the process of their colonisation.

Russians have been laying claim to not only the lands that have always been populated by Ukrainians, but also to those of Belarus, the Baltic States, Transcaucasia (South Ossetia, Abkhazia, Ichkeria) and Central Asia (North of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan).

Unlike Russia, Austria-Hungary, which was also an empire of national “peripheries”, did not have these policies. It expressly recognized the existence of other nationalities and defined their basic rights to self-determination. There were schools and cultural organisations that taught in the languages of national minorities, and until its collapse in 1918, the Austro-Hungarian Empire itself was never autocratic.

Instead, the Russian imperial grand narrative has been built on the principle that “Russia is everywhere it managed to reach”. In other words, there was no respect for conquered and colonised peoples. Russia made efforts to subjugate and assimilate them as much as possible. It did not matter if it was the Slavic Orthodox population of Ukraine and Belarus, the Catholics and Protestants of Poland and the Baltic States, the Muslims of the North Caucasus and the Urals, or even Asians of the Far East. Russian imperialism ground all of them into a single uniform mass, imposing its language, religion and culture on the conquered peoples.

However, in 1917, the Russian Empire collapsed under the influence of negative social factors, two lost wars, and the complete failure of autocracy as a form of government. However, after the suppression of national revolutions in 1917–1922 (including the one in Ukraine), Russia managed to transform itself into the neo-empire known as the Soviet Union.

The Soviet Union: A Neo-Empire

A neo-empire is a state that attempts to take over neighbouring territories to build so-called spheres of influence through the use of powerful economic and military-political levers. The Soviet Union precisely exemplifies this type of empire. The notion of the neo-empire is closely related to the concept of neo-colonialism, a policy in which a metropole seeks to retain former colonies through economic, military, or political pressure.

The USSR became a full-fledged neo-empire under Joseph Stalin’s rule. During this period, the Soviet Union carried out collectivization and industrialization, which formed the economic and military basis of the Soviet neo-empire, at the cost of millions of lives. Next, the Stalinist regime destroyed what remained of independence in the republics and autonomies subjugated by Lenin, and then began the expansion into neighbouring territories.

Collectivization

The creation of large collective farms by consolidating independent peasant farms. Collectivization gave the USSR complete economic control over its citizens and the ability to establish a dictatorship, as 85% of the population was comprised of farmers.

The Soviet Union annexed the eastern territories of Poland in 1939, occupied the Baltic states and parts of Romania, started a war of aggression with Finland, and annexed Tyva in the Far East. After its victory in the Second World War, the USSR came to control most of the Eastern and Central European countries, such as Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria and East Germany.

The USSR also attempted to impose its influence on Yugoslavia and weaken Austria. In addition to absorbing the territories it occupied before 1941, the Stalinist regime annexed the former territories of East Prussia (now the Kaliningrad region of the Russian Federation), as well as the Kuril Islands and South Sakhalin, which are still the subject of a territorial dispute with Japan.

Having forcefully obtained these new territories, the Soviet Union became a true neo-empire. At its conception, there were three plans proposed for the Soviet Union’s creation: Lenin’s plan for a federation (which was approved), a plan for a federation of independent countries, proposed by the Communist Party of Georgia; and Stalin’s plan for the republics to be incorporated into Great Russia as autonomies.

While building the USSR, Stalin could not completely go against Lenin’s ideas because he himself had turned Lenin into a national idol for millions of Soviet citizens. Instead, Stalin chose to implement his autonomization plan de jure, declaring the Soviet Socialist Republics independent, but de facto depriving them of any real agency. For example, formally, the Ukrainian and Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republics had their own foreign policy departments, but they existed only on paper in order to obtain additional seats for Moscow in the newly created United Nations Organization.

The USSR’s neo-imperial pattern reached beyond politics and economics. Stalin revived imperial traditions in both cultural and ideological aspects. For instance, he re-introduced shoulder straps which were associated with officers of the Tsar’s army. He also revived the tradition of holding balls, but for the New Year, not Christmas, as was traditional. During Stalin’s rule, military figures of the Russian Empire were made relevant again and glorified. Until then, many Ukrainian places had borne the names of Suvorov, Kutuzov, Ushakov and Nakhimov. Furthermore, after years of suppression of religion in the name of socialist ideology, during which priests and believers were persecuted and executed, Stalin restored the Russian Orthodox Church. It was officially declared as a large religious organisation, but in reality, the church was completely permeated by special intelligence officers.

On the ideological level, Stalin gradually abandoned the Bolshevik vision of a “new world” in which there would be no place for the “bourgeois prejudices of imperialism,” and replaced it with imperial narratives woven into the grand narrative of the Soviet neo-empire.

The Soviet neo-empire underwent its next major ideological change in the late 1960s, when Leonid Brezhnev was in power. Here it becomes clear that the Soviet neo-imperial mechanism, which could not function without constant large-scale and expensive projects with unclear benefits (such as the virgin lands campaign in Central Asia, the space race with the USA, the construction of the Baikal-Amur Mainline, the war in Afghanistan, support for dictatorial regimes and partisan movements in the countries of the so-called third world, etc.), required a revision of the state’s grand narrative.

It was in the 1960s and 1970s that the myth of the Great Victory in the Second World War gained unprecedented ideological scope. Simultaneously, the concept of the “Soviet nation,” which served to erase all other options for identification, began to form. Later, it was supplemented with the concept of “the Soviet way of life,” an ideological dogma of how good citizens of the neo-empire should live and behave.

How the Russian Federation built its own imperialist policy

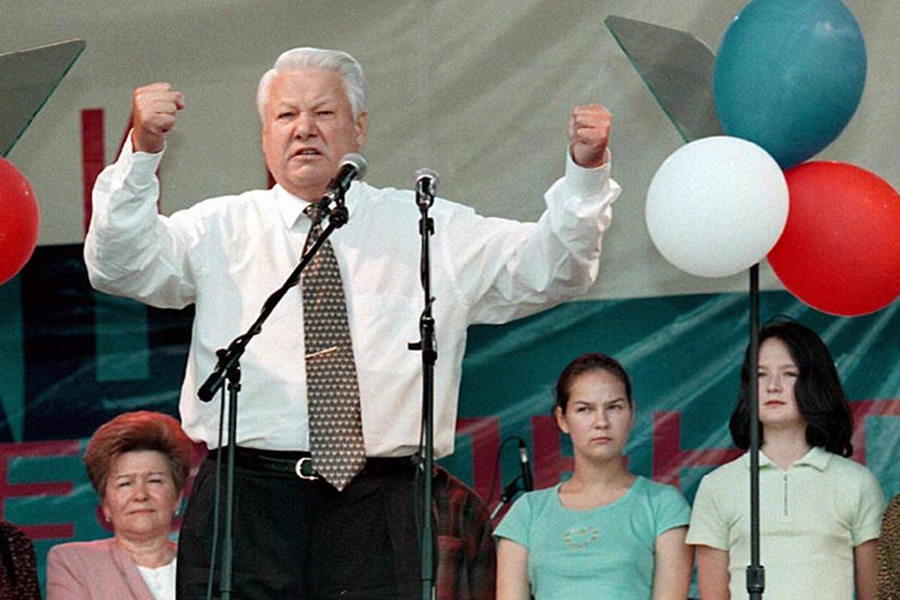

The Russian Federation arose on the ruins of the Soviet Union, whose collapse is a topic for a separate article. At first, this newly established country, headed by Boris Yeltsin, attempted to form a seemingly democratic federation. However, these aspirations were made impossible already by 1994, when Russian troops started a war with the independent republic of Ichkeria in the North Caucasus. Then, the Kremlin tightened the screws on the sovereignty declared by Tatarstan and Sakha (Yakutia).

In addition, the Russian regime began to try to maintain influence in the former Soviet republics by inciting military conflicts and declaring unrecognized state entities. This is what happened to Moldova, where the self-proclaimed Transnistrian Moldavian Republic emerged in 1991. Two “offshoots of Russian imperial aggression,” the unrecognized republics of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, appeared in Georgia.

Over the years, Russia has had its hand in the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh, maintained a significant military contingent in Tajikistan, and made numerous attempts to annex Crimea before 2014. These attempts include the separatist rebellion by Crimean President Yury Meshkov in 1994 and the conflict surrounding the island of Tuzla in 2003.

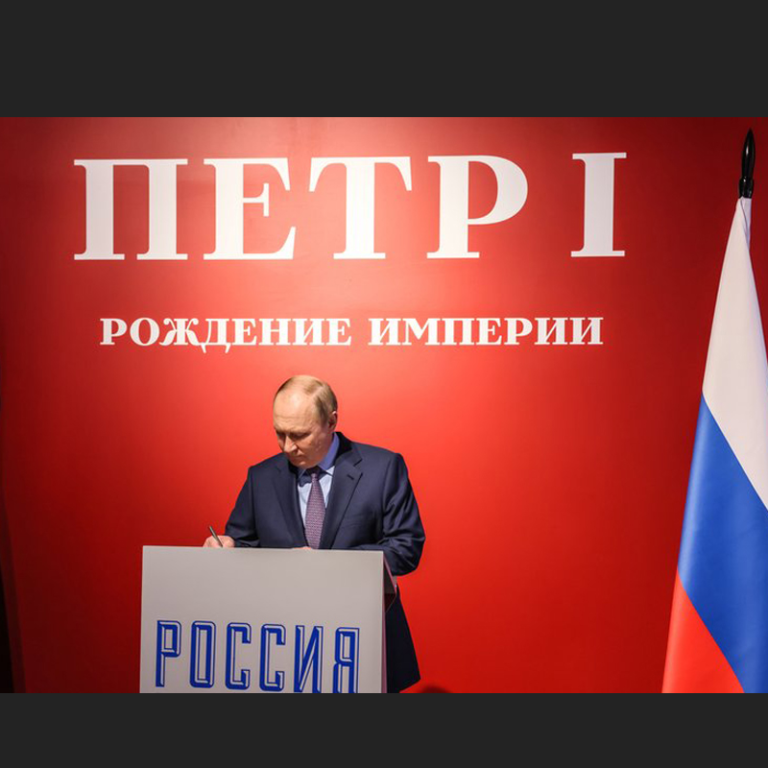

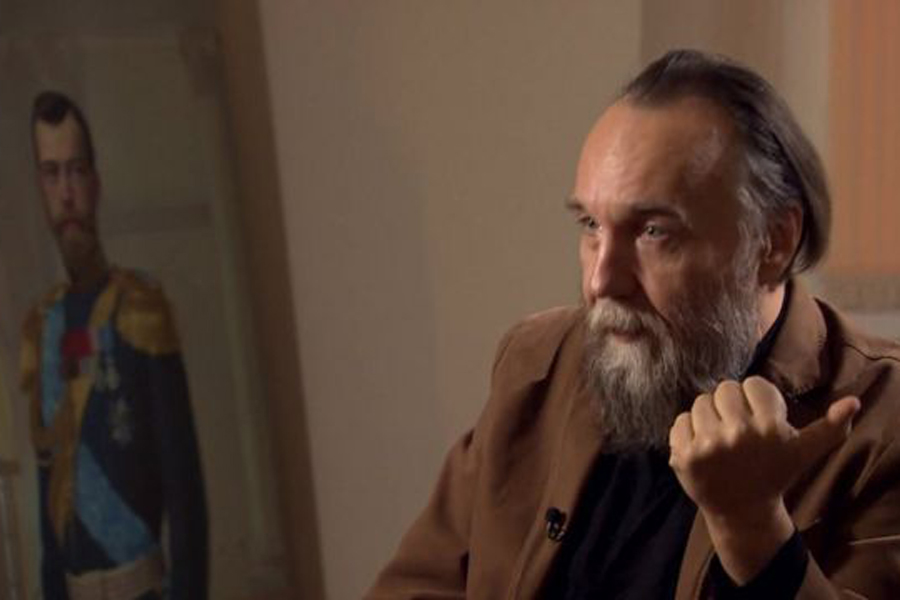

The Russian authorities resorted not only to military and political tactics to cultivate Russian imperialism; they also spared no efforts at ideological and cultural fronts. In the early 2000s, when Vladimir Putin, then a “liberal politician” and market reformer, came to power, a few “eminences grises” responsible for planting a neo-imperial ideology appeared in his entourage. These were Vladislav Surkov, a PR man with a shady past, and Aleksandr Dugin, a philosopher with an even murkier background. The former is one of Putin’s long-term trusted advisers, while the latter stayed in the sidelines but is also well-received by Kremlin. Holding high academic positions at Moscow University, Dugin is actively involved in explaining and downplaying Russian imperialism in the West and also serves as one of Putin’s unofficial advisers on ideological matters.

Vladislav Surkov actively developed a “Russkiy mir” (“Russian world”) neo-imperial doctrine which modern Russia uses to cover up its aggression in Ukraine and around the world. This doctrine was first introduced into political life by political technologist Petr Shchedrovitsky. Surkov was engaged in the formation and introduction of the main manipulations and narratives of this Kremlin concept. Initially, it aimed to protect the cultural rights of Russian-speaking citizens and diasporas residing outside of Russia. Governmental organisation “Rossotrudnichestvo” funded Russian cultural and educational organisations such as “Russian Community” and the like to expand Russia’s influence abroad. Later, this “protection” was used as the pretext for launching Russia’s wars of aggression, namely in Ukraine.

Meanwhile, Aleksandr Dugin developed and modernised the preexisting concept of “Eurasianism”, which claims that there are two pillars of civilization: Atlanticism (the USA and the collective West) and Eurasianism (Russia and its satellites), which have long opposed each other. Based on this concept, Russia has the right to seize territories that supposedly belong to its spheres of influence in order to achieve so-called collective security.

It was in the 1990s and 2000s that Russia’s imperial and Soviet past began to be understood as one cohesive tradition, which is a contradiction in itself. The flag of the Russian Empire from the reign of Nicholas II (the red-white-blue flag that is jokingly referred to as Aquafresh because of its resemblance to a popular toothpaste) is being restored alongside the music of the anthem of the Soviet Union.

In the new Russian award system, both imperial awards (such as the Order of St. George and the St. George Cross) and Soviet decorations (such as the orders of Suvorov and Kutuzov) are restored. Moreover, marshal Georgiy Zhukov and the poet Aleksandr Pushkin, who, despite being highly valued and used as symbols by the previous empires, were not so highly exalted, come into prominence. The Russian propaganda machine actively promotes them as symbols of a shared past worthy of pride in the former Soviet republics.

The new Zhukov medal is awarded to all veterans of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). Pro-government public organisations of the Russian Federation such as “Russian Community” promote the construction of monuments and busts of Pushkin everywhere. Russia is gradually developing an active cultural and ideological expansion in its former colonies.

CIS

Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) is a regional intergovernmental organisation in Eurasia created on 8th December 1991 as a political and economic union of Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. A number of post-Soviet states later joined the CIS. Ukraine was a co-founder of the CIS, but it never ratified the Organization's Charter, so it was formally only an observer. Ukraine formally ended its participation in the CIS on May 19, 2018.In parallel, the Russian propaganda machine targets the “domestic consumer”. The trend of imperial nostalgia, both for the USSR and for the Russian Empire, starts gaining momentum in the 2000s. The Russian government orders for the production of grandiose films promoting imperial narratives, such as “The Barber of Siberia” (1998), “His Majesty’s Servant” (2007), “Gentlemen’s Officers: Save the Emperor” (2008) and “Admiral” (2008). Similarly, a score of films about Soviet greatness, such as “Stalingrad” (2013), “Upward Movement” (2017) and “Time of the First” (2017) to name a few, were churned out.

Imperial ideologization covers not only the film industry but also other sectors of culture. That is, with the help of cultural products Russians are increasingly convinced that the only option for their existence is the empire, where they will be “great”, and other nations will be subjugated and will serve them.

This imperial nostalgia, in the broadest sense of the word, at times took such whimsical forms as the “revival of the Cossacks”. As a result, public associations of historical reenactors were allowed to play the role of moral police. Notably, “Cossack” public organisations patrolled the streets and actually performed the functions of the police, with a very liberal interpretation of their duties and rights. Thus, they were included in the state monopoly on violence. After Putin rose to power, the Kremlin began to gradually integrate “Cossack” organisations into the state bureaucratic system, and eventually, a separate law granted them the official status of civil servants in 2005. This essentially turned them into Putin’s “pocket army”. “Cossacks” have taken part, at first unofficially and later officially, in almost all Russia’s acts of aggression in the territory of the former USSR, including in Transnistria, Abkhazia, Chechnia, and later in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine.

"Cossack" organisations

Militarised groups of the Russian Federation that call themselves "kazaki" (no relation to the Ukrainian Cossacks).

Furthermore, “Orthodox Ethics” became a school subject that officially was optional, but in practice was mandatory, even in the regions with non-Christian populations. These lessons were often taught by priests who have no pedagogical education.

Kremlin-initiated flash mobs “St.George’s Ribbon” and “Immortal Regiment” are worth giving a separate point. Disguised as memorial events commemorating the fallen in the Second World War, these campaigns were aimed at ideologically uniting the supporters of the new empire. This ideology was promoted not only in Russia but also in the countries it included in its sphere of influence.

Just a few years before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Russian army changed its uniform to resemble that of the Russian Empire, blending it with the Soviet shoulder mark design. Even at the visual level, Russian propaganda attempts to project the image of its imperial future as a hybrid between the classical Russian empire and the neo-empire of the USSR.

A particularly revealing example of present-day Russian imperialism can be found in the office of a Federal Security Service (FSB) officer, where one can find a bust of Felix Dzerzhinksy, Soviet organiser of “The Red Terror,” alongside Emperor Nicholas II’s tricolour flag.

FSB

This organisation is the legal successor of the State Security Committee (KGB): the Soviet state organisation whose main tasks were intelligence, counterintelligence, suppression of nationalism, dissent, and anti-Soviet activities.Why imperialism is a failed policy

Russian imperialism reached its climax when Russia started an open, full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The war between Russia and Ukraine, ongoing since 2014, has reached an unprecedented scale and is the largest armed conflict in Europe since World War II.

Russian imperialism’s use of genocidal practices led to the destruction of hundreds of settlements and thousands of victims among the civilian population and military personnel of Ukraine. However, Russia does not stand a chance to take Ukraine. Despite the full-scale war’s effect on the global economy and undermining вof the existing global system of collective security and responsibility, the civilised world has supported Ukraine in preventing the spread of the imperial disease in the world. Numerous countries supply Ukraine with weapons and other necessary equipment and introduce and support unprecedented economic sanctions against the aggressor, and most Western businesses have pulled out of the Russian market to protect their reputations.

Russian society has long faced international isolation. After the collapse of the USSR, it became nostalgic for its imperial past and sought a new tzar-messiah, rather than reflecting on its own experience as an imperial nation and drawing conclusions about the counterproductive nature of aggression. This public understanding of the state system ultimately led to colossal political, economic, reputational, human and other losses. Russia’s aggressive neo-imperial approach calls into question the legitimacy of Russian statehood, because imperialism and irredentism have no place in the modern world system.

Irredentism

The desire of a state or political power to unify the entire nation within one state, particularly through annexation.A number of countries, including Syria, Belarus, Nicaragua, Eritrea, and Zimbabwe, tolerate Russia’s imperialist and irredentist aspirations due to their close economic ties with Russia. Their support helps the Russian Federation, for example, when voting in the UN or by recognizing unrecognised state formations installed by Russia. Similarly, Russia tried to bribe small island states of Oceania to increase international recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia in 2008.

Hungary’s government tolerates the Russian agenda and adopts irredentist rhetoric in international politics. For example, Hungary has begun laying claims to the territories that Hungary lost under the Trianon Treaty of 1920 following the collapse of Austria-Hungary. In response, opposition to Hungarian membership in the EU and NATO has grown among European politicians.

Russia’s fate is clear. Its imperialistic and irredentist ambitions will eventually lead to fundamental changes in its very existence after the victory of Ukraine and its Western allies in the war. Experts and average people who know history well agree that the disintegration of the Russian Federation into a number of fragmented states fighting for their sovereignty is only a matter of time. The Russian pseudo-empire is failing and no matter what decisions its leadership makes, all of them, even if they can make temporary improvements, will lead to its collapse.