This episode of “Ukraine Through the Eyes of Others” features Jennes de Mol, the Former Dutch ambassador to Ukraine from 2019 to summer 2024, who participated in the investigation into the downing of flight MH17.

In this interview, Jennes discusses the challenges and emotional toll of diplomacy in times of crises, in particular following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

The conversation covers the evacuation process, the impact of war on diplomats, and the resilience of the Ukrainian people who live in a war-torn country. He also addresses the ongoing challenges of maintaining diplomatic relations with countries that continue to engage with Russia, highlighting the nuanced decisions and moral considerations involved.

You became the Dutch ambassador to Ukraine in 2019. Earlier, you also worked in Ukraine, but in a different role. You were assigned to participate in the investigation into the downing of the flight MH17. Throughout these years, how has the image of Ukraine changed for you? And, if this is the case, how have you personally changed?

Well, my history goes back to 1996. I worked in Moscow then and had the opportunity to travel to Ukraine. So, I flew to Odesa with a friend, a Belgian. Then we went to Simferopol, to Sevastopol, Yalta. I’m an archaeologist by training, and I studied law as well. I wanted to see the excavations in Crimea, Feodosiia, Kerch, and all these places. It was the time when you still had “kupony” (Kupony, eng. coupons, used to be a form of currency in Ukraine in the 90s — ed.), and the economic situation was challenging. When I came back in 2014, there was already a lot of progress, the Maidan Revolution just took place.

In the summer, I was asked to leave St. Petersburg, where I was working at the time, to support the embassy’s activities. We just had the most significant disaster since the Second World War, an enormous amount of Dutch casualties from the downing of MH17 (Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 was shot down over the east of Ukraine on 17 July, 2014, by a missile fired by Russian forces, killing all 298 people on board — ed.). For me, that was a return. I immediately had to start working. Then, after about one and a half months, I could go to the next assignment. In 2019 I had the chance to select a new post. We discussed what that should be. I chose Ukraine because of its Euro-Atlantic course and the possibility of doing things there. I was very happy to be there. Having been here for so long and in different moments, I think it’s good to see the differences. They are huge. I think after the Maidan, Ukraine changed even more rapidly. These five years have had an enormous impact.

In your interview for Dutch television a year ago, you talked a lot about the sad experiences of your life, about the evacuation from Kyiv, how, alongside your colleagues, you stayed in a Polish monastery due to a lack of hotel rooms, and how eventually you came back. How has this experience of living in a country during wartime affected you as a foreign citizen and an ambassador or diplomat?

I arrived in 2019, and this was a very active country. A lot was going on. It was a time of the turbo-regime, turbo-government; Zelenskyy had a monobil’shist’(majority in parliament held by one party — ed.), so a lot of things were happening. Then Corona came. Corona led to a standstill, although the situation here was less severe than, for example, in the Netherlands. It allowed us to travel a little bit and see things. Then, of course, the full-scale war started. I understood there would be a severe situation [with Russia], which developed over November 2021. At that time, I understood that we had to prepare for war.

Were you notified, or was it just in your thoughts?

No, we were not noticed. I got the information, and it was clear to me that we had to prepare. You hope for the best but prepare for the worst. That is the attitude. Then it happened, and we had to evacuate. Also, before that there had been a very negative experience with evacuations in Afghanistan where people were evacuated too late. It had an impact on the situation. Leaving is one of the most bizarre moments because you don’t want to leave. This is contradictory to everything that I stand for. I want to be there, where the action is, and where I can be relevant. Having to leave was difficult.

First, we went to Kyiv, where we set up a consular hub to support people, especially Dutch people, who would leave the country. Finally, we had to leave ourselves after being informed that the war had started. Then suddenly, you’re in Poland. We looked in Jaroslaw for a place to stay, but all the hotels were full since many people were leaving the country. And we were among them. We ended up in a bad American B-movie, looking for shelter in a monastery. After one night there, we went to Rzeszow, where more embassies were active. That was a good decision. But from that moment onwards, there was only one desire — to return. I was extremely happy that we managed to get back to Ukraine in April.

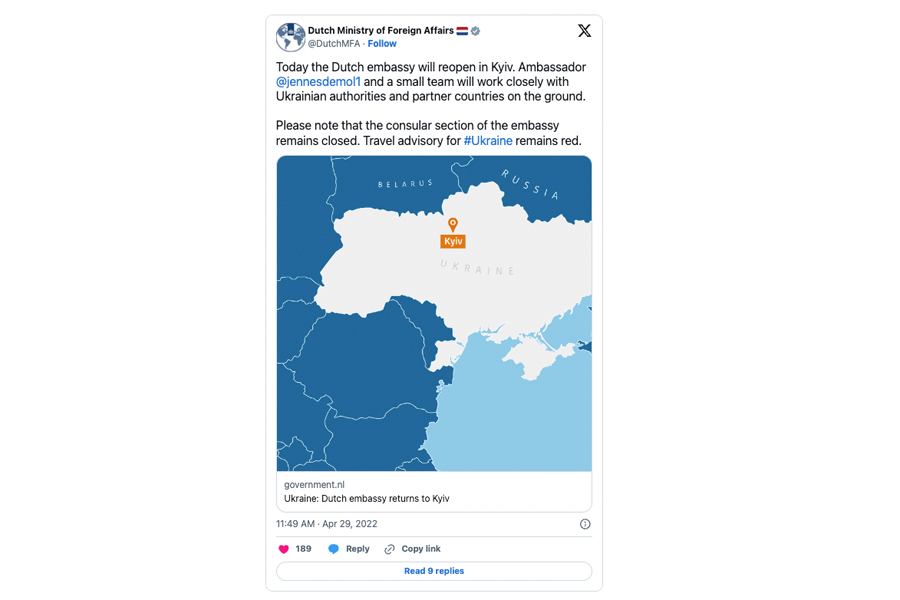

You were one of the first embassies who came back.

Yeah, a couple of them never left. The Holy See (the Vatican’s diplomatic mission to Ukraine that represents religious interests and supports the Catholic community — ed.) never left, and the Polish colleagues. We were one of the first to come back. That was quite an experience, I remember very candidly that we drove from Lviv via Zhytomyr to Kyiv. It was blocked because some of the viaducts had been bombed. We had to drive through Irpin. Suddenly, there was war damage along the streets from Zhytomyr. You end up in a war zone, and you come to understand that every second house has been damaged. And that this was so close to the city, that we were very close to disaster. The atmosphere in the car became very silent. It had an impact on all of us. Then we drove into the city, which was also bizarre since the town was empty. No people on the street, shops closed, and some young people on “samokaty,” (Eng. scooter) going through the city, which was very strange.

And afterwards, how was it living under the bombs, with electricity cuts, with guards?

Well, you adapt. In the beginning, we were very serious with the alerts. I was not alone. I was with the security team and with colleagues. We came back. We settled. We had a safe place. Of course, you get used to the alarms after a while. It was not for the first time. I had experience in difficult circumstances in Afghanistan. You get used to it. I was lucky that I was able to go back to the residence where we lived. We had a shelter there. However, when the air defence started working, it was impressive. The whole house shook. It is very strange to hear drones flying over the river where we lived nearby. So that had an impact. You also see the anxiety of the people around you. Everybody has their own story.

But you mentioned that you worked in conflict zones, such as Afghanistan. Was it different between here and there?

It’s different. You can’t compare it. For example, in Afghanistan, we really had a situation where we were attacked with grenades. They flew in, and we had two seconds of alarm, and then “boom”. You immediately knew the result. The alert goes on here, and you don’t know exactly what will happen. You still have time to go to the shelter, but you don’t know what will happen until you hear something or get information via the telephone. Anxiety lasts longer here. That’s the difference.

What are your plans after the end of your ambassador term in Ukraine? Will they be connected to Ukraine or the Ukrainian issue in general?

I asked for a prolonged period of my assignment here because I thought I was not ready to leave in 2022. We had just had the Pandemic, which was difficult. The war started. I had just returned to Ukraine. There was so much to do in the military, economic, and humanitarian fields. I learned Ukrainian and felt like I had to do something and contribute. So I asked for an extension. But also, it was clear to me that the embassy would grow and our activities would increase. Some of our colleagues left to go to a new assignment. For continuity and institutional memory, it was essential to have somebody who at least knew what happened before the full-fledged invasion. Because let’s not forget that the war also started in 2014 with MH17. So I thought that was important. That made me decide to stay.

How did you decide to speak Ukrainian? I even know that you participated in the national unity dictation (an annual event where people nationwide simultaneously write a dictated text in Ukrainian to promote the language and foster national unity — ed.). Why did you learn it when you can speak fluent Russian?

When I arrived in 2014, I could communicate with everybody in Russian. That was more or less normal. In 2019, I turned on the television, and I saw a lot of Ukrainian language. I understood something, but not entirely. I understood I had to change because the situation had changed in these five years. Initially, I spent time trying to learn the basics of Ukrainian. But during the Pandemic, I also had, like everybody, more time. We had Zoom opportunities, so I intensified my lessons and had lessons twice a week. Then I made progress. But it has also become, I would say, a political statement. Because for me, all of a sudden, I wanted to, as a diplomat, win the hearts and minds of Ukrainians. Especially in times of war, when identity is being questioned… and bombed even, language is critical. Of course, I knew I would not be fluent in Ukrainian, but it was enough. But I can listen to Ukrainian radio. That gave me information, but it also gave me a language course. Now, for example, in interviews, when I prepare the text or the questions, I can answer them in Ukrainian.

Do you have a favourite Ukrainian song? You said you listen to Ukrainian radio, but maybe you also listen to Ukrainian artists, music, and so on.

Yes, I like Vakarchuk and Okean Elzy. I like Alina Pash, and I know there are things around her (Okean Elzy is one of the most popular Ukrainian rock bands, with Svyatoslav Vakarchuk as the lead vocalist and frontman. Alina Pash is a Ukrainian singer who was involved in a public scandal before Eurovision 2022 — ed.). But I like that. Especially when I was in the beginning here, I heard her national anthem song during one of the first national holidays I attended.

Speaking of identities, you told us you worked in Russia in the 1990s. You previously served as a cultural attaché and consul general in St. Petersburg. How was Ukraine perceived then, for instance, in Russia and the Netherlands?

Now we talk a lot about colonialism, about the imperialism of Russia. At that time, when I had meetings with Russians and Russian officials, they could not understand that, let’s say, the independent republics, now I’m talking about 1995 and 1996, were independent. For them, it was still their territory. And you could feel that.

At what levels? Politically, culturally?

No, you felt it at the working level. People still thought that the composition of the Soviet Union was still there, that it was one territory. But these territories have become independent. The republics, Georgia, Ukraine, and Belarus were independent. But then, later on, it changed. When I was back in 2011, a lot had already happened with the elections and the Bolotnaya demonstrations (demonstrations in Moscow against Putin — ed.). We had the Arab Spring, and I think the political situation became very grim for the people. And then, in 2013, with all the discussions about EU relations between Ukraine and the EU and Yanukovych’s hesitation to sign agreements, you suddenly heard a lot of propaganda on Russian TV. At the beginning of the illegal annexation of Crimea, you heard “Krym nash, fashysty, banderovtsy,” (Eng. Crimea is ours, fascists, Banderites) every day on the TV. It was horrible. The whole propaganda machinery started working, it became impossible to watch Russian TV.

How was it in the Netherlands? For your relatives or your family?

The situation differed in the Netherlands because people didn’t know much about Ukraine. Gradually, people became aware of it. In 2016, we had the referendum. We learned about Ukraine, of course, because of football. We were playing football in Kharkiv at the European Championship in 2012. But the illegal annexation was unacceptable to us. People were aware of what was going on and had a perfect stance towards Ukraine, which developed after the beginning of the full-fledged invasion.

But still, in 2016, the Dutch voters voted against the EU-Ukraine treaty in general. In your opinion, has the attitude changed since then? Or, for instance, has it changed before? After MH17?

After MH17, which was a disaster for us and shook the whole world, we came to understand very clearly what was going on there. People were upset. We wanted truth, accountability, justice. In 2016, the situation was different. There was a referendum on the EU-Ukraine association agreement. The turnout was a little more than 30%. There was a slight majority that voted against it. The referendum was not as much about Ukraine and it was not legitimate at all. But it was a sign of dissatisfaction about what was happening in the Netherlands. I also think about European politics in general. That was the sentiment. But at the end of the day, we signed it. Later on, because of the full-fledged invasion, the situation dramatically changed. People understood that the aggression came from Russia, that this was illegal, and that something had to be done. There, the course of action of our government was obvious.

Referendum in the Netherlands of 2016

Dutch Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement referendum. On 6 April 2016, 61% of the voters who took part in the referendum voted against the approval of the agreements.We have already discussed EU integration and the relationships with Ukraine, the EU, and NATO. Mark Rutte said that Ukraine could not become a member. Is there any understanding of when it might be possible, and can we discuss a timeframe for both cases and alliances?

That’s difficult to say because I’m not a politician. I’m a civil servant. However, I see that in both instances, the future of Ukraine is within the EU and NATO. Now the process of negotiations starts. About the EU, it is obvious. We came from a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (an agreement with Ukraine, which reduces tariffs and aligns regulations to deepen trade and economic ties with the EU — ed.). We have a visa liberalisation agreement (an agreement allowing Ukrainian citizens to travel to the EU for short stays without a visa — ed.). There are also trade arrangements. Now we’re talking, and we’re waiting for the European Commission to come up with advice on when the intergovernmental conference can start to talk about the accession. This is a process that takes time. The Dutch stand is a merit-based approach. We are strict about fair conditions, and we want to be engaged. Regarding NATO, there has been a declaration by NATO states that the NATO-Ukraine cooperation council is also in place, which states that the future of Ukraine lies within NATO. It’s difficult to say exactly what the timeline will look like. But it’s a working process. This is a question of growing towards each other.

What do you think about peace talks that have increasingly appeared in the press, publicly or privately? Is it wise to start them? Are we in a strong position, or is it better to seize the initiative on the battlefield?

Well, I’m a diplomat, so I read an article analysing all the military conflicts in the world as of 1945 and how they were settled. Most of them have led some kind of agreement. However, many of these agreements lack clarity on their conclusion, so the issues continue for a while and might flare up again. Then, there are peace settlements. There are all sorts of varieties. There is a need to talk. But the question is, is there trust, and is there a basis for talks? We think it’s up to Ukraine to decide when the time is right, but we can help with preparations, with brain power, with support, and making the conditions right for Ukraine to decide for themselves when the time is right to come up with peace negotiations. We are very supportive of Zelenskyy’s peace formula (ten-point peace plan proposed by the Ukrainian government, which includes the withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukraine, release of all prisoners, restoration of Ukraine’s territorial integrity, etc. — ed.), and we’re all doing all sorts of outreach as well, trying to support and get as many countries onboard in this peace formula as possible.

Do you think the goal of the Peace Summit was to create new alliances, similar to entente, or was there another objective? (the interview was recorded before the Peace Summit — ed.)

President Zelenskyy’s peace formula is the only one relevant to us, so we support it. It’s important to have as many countries onboard as possible. There’s a lot of outreach all around the world. I also see active Ukrainian diplomacy reaching out to African states, Latin America, Asian states, and those countries who really could make a difference. It’s important to be together. There are three topics that were highlighted as a plan for the Peace Summit (international summit on peace in Ukraine held in Switzerland in June 2024 that engaged representatives from over 90 countries — ed.): the nuclear issue; the exchange of prisoners of war, civilians who have been detained illegally, and how to bring them back. And there is the question of everything related to the Black Sea: the freedom of movement on the Black Sea and the grain initiative. It’s essential to stay together and make sure that all countries adhere to the UN charter and make a clear statement that aggression, as we’ve seen from inside of Russia, is unacceptable.

What would you say about Ukrainian diplomacy in general? What are the main successes for now?

I’ve seen an enormous intensification. I’m extremely pleased by what I see because, first of all, there’s outreach to more and more countries. Even last year, Ukraine opened about ten embassies in Africa, which is important because every country matters, and you have to invest in relationships. The same is happening in Latin America. I was in a meeting where they [Ukraine] also showed their intentions to be more active in Latin America. That is crucial, and the same should happen in Asia. Another step is to acknowledge the problems of others. What I like very much is the creativity of Ukrainian diplomacy. You do a very good job debunking disinformation from the Russian side. You’re creative. You’re eloquent. This is very, very important. At the same time, I also see enormous resilience in your people. Aso, you’re convinced of your position. This has an impact on us.

But are there any disadvantages or any points that we may improve?

Yes, there is always room for improvement. But you develop very fast, and I would not share my criticism. I’m a diplomat. I do that in closed circles. But, overall, what I see happening is impressive. And you know, diplomacy is not only about diplomats. Diplomacy also involves the work of NGOs. You have a lot of NGOs who are highly active in Brussels, in capitals. They are very vocal and are doing an excellent job. You have journalists who do a lot of good work. You have academics. You need the brainpower, the ideas, and the creativity of the broad scope of your society. I’m impressed by what I see, especially from the non-professional diplomats. They are very informative, but also they are pushing. You know, we play chess at different tables. So it is essential to bring them together but accept that they can be played at different tables.

The Netherlands and Ukraine share a long history of diplomatic relations, which began long before the 20th century. Which aspect of these relations would you like to highlight or discuss?

Now it’s all about stopping Russian aggression. Therefore, military support is crucial. We came from essential backing in 2022. We went to Pantserhouwitsers (self-propelled howitzer — ed.). We went to radar systems, a tank coalition, and Patriot systems, and now we’re with F-16s. What we have, we give. What we cannot provide — we try to arrange, finance, and come up with coalitions trying to help you, like the tank coalition (an alliance of countries that provide Ukraine with tanks and armoured vehicles — ed.). Now we’re in the ammunition coalition, trying to give you enough ammunition for your instruments at the front line. Innovation is important. The drones are flying, and this is a new element. Innovation in industries, such as military industries, is crucial. So we will invest in cooperation there as well.

The financial part is crucial for the economy to continue to function. Otherwise, you will get implored in society, and then there is nothing to fight for and defend. It is essential to support the economy with instruments that support economic development. But also maintain budget stability in the country. We are working with the IMF (International Monetary Fund), EBRD (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development), and all these international organisations. Then, of course, there is the humanitarian part. We assist international organisations such as the UN and UNHCR. But apart from that, there are also other issues. We are heavily involved in de-mining. People cannot come back to their villages if there are so many mines. Imagine, the area of Ukraine which is mined, is about three to four times the size of the Netherlands. It is mined and there are unexploded ordnances. So the problems are immense and we have to tackle them. We work closely together to develop instruments, trying to finance all this.

I also want to highlight that we are very active regarding accountability. The war crimes of the Russian Federation must be stopped, documented and prosecuted. We work together with the ICC (International Criminal Court). We do a lot with the Ukrainian Prosecutor General’s Office and with the Ministry of Justice, trying to set up claims commissions, damage registers, and acknowledgment of the damage done to persons and the country as a whole. And this is very, very important. That keeps me busy because I also try to be active in all these fields.

It is no secret that the Netherlands is one of the top partners in terms of investment and military aid. Speaking of priorities, if war continues, what will these priorities be? And sorry for the question, but when will we see F-16s in Ukraine?

I hear that a lot, and actually, I’m not a military officer. But what I know is an F-16 is not like me giving you the key to the car — and please drive. You now drive an Opel, and then you drive a Mercedes. It takes a lot of training. Pilots are being trained as we speak. It means logistics and maintenance. Airfields need to be prepared. You need to have the right equipment. You need to be able to use the full spectrum of the possibilities and capabilities of the plane which we’re achieving in a coalition. There are other partners, such as intellectual property rights on software in planes and jets. All this needs to be taken onboard. I understand the urgency because I also see what is happening in the country. I know that there’s a need for air defence. Luckily, there are now more and more initiatives and as far as I’m aware, things are progressing. You also see in the news the first signals that the planes will fly soon.

According to the Institute for the Study of War’s research in the Kharkiv region, the absence of the possibility of striking targets on Russian territory compromised Ukraine’s ability to defend itself. What is the Netherlands government’s position towards the possibility of striking the territory of the Russian Federation?

What’s going on in Kharkiv is horrible. I love the city very much. I’ve been there a lot of times. We’re open to whatever ideas Ukraine has. Ukraine is entitled to protect itself and defend itself. This also means that you will have to hit the enemy where it hurts. That’s it.

What about sending troops to Ukraine as part of a coalition or NATO? We heard that idea a lot from President Macron and our Baltic partners. What is the Dutch government’s position on this?

This issue is not on the table. But yes, it’s being discussed. It is more relevant to the whole question of training troops and preparation of soldiers that will be used after mobilisation. We always said we have an open mind. We take things pragmatically. We look at the possibilities of helping. But it’s Ukraine that decides at the end of the day. And we want to provide assistance that is effective and efficient. We’re also looking forward to ideas from the Ukrainian side on how to be more efficient in our training activities.

Going back to the MH17 case, what do you remember from that experience, coming here, seeing all the horrible things, hearing about it? Can you talk a little bit about it?

For me MH17 was the beginning of my professional involvement with Ukraine. Of course, there are a lot of lessons to be learned because of the prosecution of indicted persons. Lessons learned from a legal point of view. We cooperate within the framework of the Joint Investigation Team with Ukraine and with other countries like Australia and Malaysia. It also makes me repeat that the war started in 2014. I remember very well how we were trying to get the remains of the plane and the bodies back to the Netherlands. That was very, very emotional. I remember very well the day when more than a hundred black cars drove over Dutch roads from Eindhoven to Hilversum. I know some people who have lost relatives. They deal with this every day. For me, MH17 is sort of the leading principle in my work here in Ukraine. When I arrived in 2019, I went to see the contact line. We had a lot of activities there with the UNDP. We worked on a lot of community security issues. I went to Vugledar, Bakhmut, and Stanytsia Luhanska to see all these places. And it really hurts to see what is happening there. But I was there, and the war went on. It was called low-intensity warfare. Every day, four or five people died. That had an impact on me as well. This is what I carry with me.

You travelled a lot, especially after the full-scale invasion, especially to the towns and cities affected by the war. Can you name a place or a town you visited that became a favourite or a key town for you for some reason?

Well, it’s very difficult to say, because I have a lot of emotions with a lot of towns. They’re all different. What had a very profound impact on me — was going to Kherson after the liberation. We were invited to go by train to Mykolaiv and then by car to Kherson. We were in a city that still stood, but everything was robbed [by the Russian forces]. There was no electricity. People were walking around dazzled. At the end of our visit to the city, we spoke to a lot of people, and we went to see a police centre, which had been used as a detention facility by the Russians. It was just awful. It was brutal. And I remember [feeling] that Russian aggression was so close, and that really had an enormous impact. So that led to a situation in which I was a hundred percent motivated to do everything I could in the field of accountability to help Ukraine stop this. So, Kherson was really a place that became very symbolic for me. But I’ve been to other places as well, so it depends on the people. I love the Carpathians, I love to go to Yaremche. I also loved the road between Vinnytsia and Bila Tserkva. It goes to a very empty space, and it’s beautiful, it’s agricultural, it’s endless. I’m from a small country, where everything is full, we optimise our landscape and our land. There, you see this glowing beauty, and that also had an enormous impact on me. But also just visits to people, whether it’s Chernihiv or Kamianets-Podilskyi. I love that as well. I remember walking in the botanical garden of Chernivtsi, which was just beautiful.

You talked about accountability, which is a critical point nowadays. In a recent interview with the New York Times, Volodymyr Zelenskyy discussed countries that are still seeking to retain trade and diplomatic ties with Russia. In your opinion, why is this happening? The West is no longer confident in Ukraine’s victory? Or are there some economic, political reasons for that?

I think you mentioned a couple of things, and they need to be nuanced. I think diplomatic relations are still there because you have to open the channels. You have to, one way or another, talk to each other, however difficult that might be. And then there are sanctions, and the sanctions are very severe, they have an impact, but they can be more effective. Some companies have been active in the Russian market for a long time. Due to sanctions, some have decided to cease their activities to avoid fines and other penalties. Then there are companies that are still active, perhaps not under the sanction package or the sanctions regime, and the question is whether from a moral point of view, these companies can continue their operations there. The consumer also plays a role in sending a message. Then there are the issues related to companies that have difficulty selling their assets [in Russia] because there’s a lot of pressure on them as well. It’s complicated, and personally, when I buy goods, I look at where they come from and what the background of the company is. So I think that it’s also important for us as individual consumers — to look at the whereabouts of companies and make a decision for ourselves.

You don’t buy Russian products?

I don’t buy Russian products, and I don’t buy products from companies [that are still active in Russia]. I try to at least avoid those who are actively involved in sponsoring the Russian state budget. I don’t want that, personally.

On your social network pages, you are very active and open about your experiences, discoveries, and travels. Speaking of your last months here in Ukraine, what would you post to write as a farewell message on your Twitter, for instance?

I haven’t thought about it yet. First of all, I want to be active because I want to talk about my experiences in Ukraine. This helps people to understand how life is [here]. I get a lot of questions about how it is to live in Ukraine. People have difficulties — they look at the news and see horrible things, but they think that the whole country is ablaze, which is not the case. If you go now outside Kyiv, you see another type of life, there’s anxiety, but at the same time, life continues, it’s very difficult to understand [from afar]. You could say, well, “Stay in the fight”. That’s also a slogan you hear. Perhaps I would wear a shirt or a T-shirt. You have all these T-shirts now, I love them very much. I have a collection at home. But the basic one is “I am Ukrainian”. And although I’m a diplomat, at a distance, I became a little bit Ukrainian after five years. This country has become part of me. Although I’m still professionally capable of keeping my distance and protecting Dutch interests, this is my task. But I will wear the “I am Ukrainian” with pride.

supported by

This publication has been produced with the support of the ‘Partnership Fund for a Resilient Ukraine’. The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Ukrainer and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Fund and/or of its financing partners.