‘Hear the Voice of Mariupol’ is a series on people who survived the Russian blockade of the Ukrainian port-city Mariupol in 2022, and managed to evacuate. Two years later, we meet them again to learn how their life has changed, and their opinions on the full-scale war.

F or this piece, we spoke to Halyna Balabanova who used to coordinate Khalabuda (which means ‘Treehouse’), a volunteer hub that helped the locals and military personnel in the Mariupol area.

The spring of 2014 was the first time when the Russian military seized Mariupol. The city stayed under Russian control for two months, from April 13 till June 13, to the day. Back then the city was liberated by several military units, including the Azov Volunteer Battalion, a new regiment which became one of the symbols of Mariupol at the time.

Photo credit: “Azov”.

Russia, however, never gave up on trying to conquer Ukrainian territories, and launched a full-scale invasion in 2022 to seize the entire country. Mariupol, separated from occupied Donetsk by a mere 15 kilometres, became one of the first Ukrainian cities to be attacked. The city’s residents, who were used to living near the frontline, sprung into action, and dedicated themselves to volunteering and mutual assistance.

Volunteering in Mariupol to help the displaced of Donetsk before the full-scale invasion

After Mariupol was liberated by the Ukrainian army in 2014, the city became home for thousands of IDPs from the Donetsk region, the cities, towns and villages of which have languished under Russian military occupation. The IDPs and volunteers from Mariupol took a proactive stance and started opening hubs, creative spaces, as well as recreational and community centres. We covered some of these stories back in 2017.

Photo: Dmytro Bartosh.

Halyna’s volunteering journey as a native of Mariupol also began during the ATO [the military operations in the East of the country were called ATO, the Anti-Terrorist Operation, between 2014 and 2018]. She initially offered her help to a Mariupol NGO called Skhidna Brama [Eastern Gate], which turned into a hub called Khalabuda. Its team facilitated cultural and educational projects, supporting businesses and social improvement. Operating as a free space, the hub hosted activities, helped IDPs with evacuation, housing and humanitarian aid, and assisted the ATO veterans and everyone who needed help. Khalabuda was one of the places that changed Mariupol for the better and showed that despite the proximity to the demarcation line, it was possible to live and build one’s future in the city.

Photo: Dmytro Bartosh.

However, the Russian authorities’ imperial ambitions destroyed it all. On the morning of February 24, 2022, Halyna and other Khalabuda activists began repurposing the space to host victims of the war, gathering humanitarian aid, and assisting the civilians and the military. When the situation in the city became critical, she evacuated. She left on March 16, the day the Russians bombed the Mariupol theatre, killing hundreds of civilians seeking shelter inside.

Photo: Khrystyna Kulakovska.

How Halyna’s life changed since the occupation

Having fled Mariupol, Halyna settled in Lviv, a city that already welcomed a lot of IDPs fleeing Russian aggression. Over the past two years, she adapted to living in the Halychyna region, yet she still notices the difference between living here and in her native Pryazovia region.

“For me, it wasn’t just a change of scenery, the very rhythm of my life changed as well,” she says. “At first, Lviv seemed very slow-paced to me, and initially, it drove me nuts. It took me a year to realise such a pace might be better for my mental health than constantly running somewhere. When I fled Mariupol, as soon as I reached somewhere with an internet connection, I commented on a Facebook post by my friend who was gathering a project management team nationwide, something along the lines of ‘I’m ready, let’s do it’. I mean, I was anxious to rush into the whirlpool of events, however, I guess my fate knew better, and I guess that’s why I was lucky to have ended up in an environment with its somewhat slower Lviv rhythm.”

Over these past years, Halyna changed her field of work, so Khalabuda proceeded without her.

“My initial task during my first year here was to gather a new team and teach them everything I knew, helping them develop projects that were interesting to them in the place where they lived. Thus, Khalabuda’s operation also changed compared to what we were doing back in Mariupol. After that, I saw that my role was basically over and that I could step back and change my participation [from leading] to offering advice.”

Photo provided by the interviewee.

After evacuation from Mariupol, Khalabuda relaunched in a new space in the city of Cherkasy. As in Mariupol, its volunteers provide humanitarian aid to the citizens and people from neighbouring settlements, host events and assist with military drone repairs. The hub also functions as a co-working environment, and a space for social initiatives. Likewise, one of the team’s most important projects was offering networking and support opportunities:

“[This is] a project offering support and tools for talking to people whose close ones are in captivity or the military,” says Halyna. “We often see such projects being reduced to ‘so we have some relatives waiting for someone’s return, and there we have some people who miss and need them’. In contrast, our project also involved other NGOs who see those people as their potential [clients], and those NGOs taught people how to communicate with [sensitive groups] without causing harm.”

After retiring from the Khalabuda team, Halyna decided to partake in projects aimed at helping the general public. She shares that despite many communities and organisations offering to hire her, she has some internal barriers preventing her from joining.

“Accepting [any of those offers] was hard for me, as those were established teams, unlike that of our Khalabuda. It wasn’t a team that just emerged from a circle of friends and like-minded people. So over the last few months, or rather over half a year, I’ve been experimenting and working with different teams, joining some of them as an advisor, all the while trying to find an emotional fit with those established teams.”

Photo provided by the interviewee.

These days Halyna is a part of the USAID’s Enhance Non-Governmental Actors and Grassroots Engagement (ENGAGE) programme. While being hesitant at first, the woman came to realise that her time at Khalabuda was over and she was ready to move on:

“So I’m working with organisations seeking funding for doing something in Ukraine right now.”

A failure to provide basic living conditions: news from Mariupol

Halyna mostly gets relevant news from her hometown from the people she knows personally.

“I have several people out of my immediate social circle staying in Mariupol. Every now and then they post something and get in touch. To me, they are a kind of an additional filter of what is really going on there, no matter what the Russian outlets chose to broadcast.”

From her sources, Halyna sees that over the past two years since what the Russians called “the city’s liberation”, they failed to provide basic living conditions for the citizens who opted to stay. While Russian propaganda is tirelessly creating the illusion of normalcy for those living in the city, this mirage vanishes as soon as the Russian cameras stop rolling.

“To me, this is a simulacrum of Mariupol— a simulation of the city, and its citizens and activities at every level.”

Due to the hostilities, Halyna’s home in Mariupol was burned inside and ruined on the outside. However, since the building is located in the central part of the city, the occupation authorities made some superficial repairs and gave it a new foreside, so it looks picture-perfect on the outside, but has no residents.

Photo provided by the interviewee.

As soon as one leaves the downtown that the Russians are renovating with great fanfare, and goes to the outskirts or the neighbouring towns, there are still ruins. The residents in those places are forced to rebuild their homes on their own, as the occupation authorities aren’t interested in helping out.

“Of course, most buildings there are single-family homes, so it’s a bit easier for them. Like, having a forest or a grove nearby enables them to heat their homes with makeshift woodstoves,” says Halyna, “yet some of my acquaintances have spent over a year with no electricity. In winter I can imagine them putting some food outside to keep it from going bad, even if it’s three or four degrees centigrade outside. In summer, however, that’s just impossible.”

Halyna’s acquaintances share that the homes that are used for Russian propaganda are connected to the grid. Although they may have gas and electricity supply, this service is very poor. The heating is irregular, and the water is unfit for human use.

“The water quality is horrible,” she says. “I have no idea where they [the invaders] get in from now, or whether they pump it from our water reservoir… I mean, it’s not even processed water, it’s outright unfit even doing the dishes, or even for mopping the floors. Still, one can argue that the city does have some kind of tapwater.”

Another persistent problem is the lack of jobs. The Russian occupation authorities can offer nothing but clearing the debris and driving public transport. However, public transport is scarce, because most buses were destroyed by the Russian military during their attempts to take over the city, which puts a huge strain on the drivers.

“Someone I know told me that their relatives in Mariupol tried to get at least a job as a driver, however, the pay is poor and the hours are crazy. You need to be up and running by four am. And there’s the problem of the lack of vehicles, so people either use their private vehicles or have to change many times to get places, so a one-way trip can take three hours.”

Because of that situation, some car owners earn their living as private taxi drivers. This job can be dangerous. Halyna shares the story of one acquaintance who went missing on his first-ever shift as a taxi driver.

“I’m working hard on letting go, but the meaning of home is never the same”

Halyna spent her first year in Lviv looking for a job and a place to live. However, at some point, her traumatic memories took her over, so she had to take some time off and take care of herself.

Photo provided by the interviewee.

“I didn’t call that a vacation, because, to me, it was like some sort of a summer break. I took up drawing and reading therapeutic books, including those written by people I know. And then [Ukrainian writer] Tenia Kasian’s book came out. I’ve read the first half and was like, ‘I guess that’s exactly what I needed at the moment.’ Not some repeated trauma, not re-living the past events, but an introspection, a comparison of how other people reason with themselves, and how they live through the same experiences that I’d been through.”

"Things we share. How to stay human in time of war and as it ends"

A book by Ukrainian writer and journalist Tetyana Kasyan. It covers how Ukrainians grasped the outbreak of the full-scale war, how its escalation affected [the Ukrainians], and highlights the likely future consequences of the war for the society.Halyna adds that while initially reading such books describing Mariupol and the trauma caused by the war took a toll on her, she felt that it was important to experience what her city (as well as the Pryazovia and Donetsk regions) had once been, even if only through those books. She recalls how on every page she kept coming across mentions of places and even people she used to know.

Photo: Andriy Bolotonov.

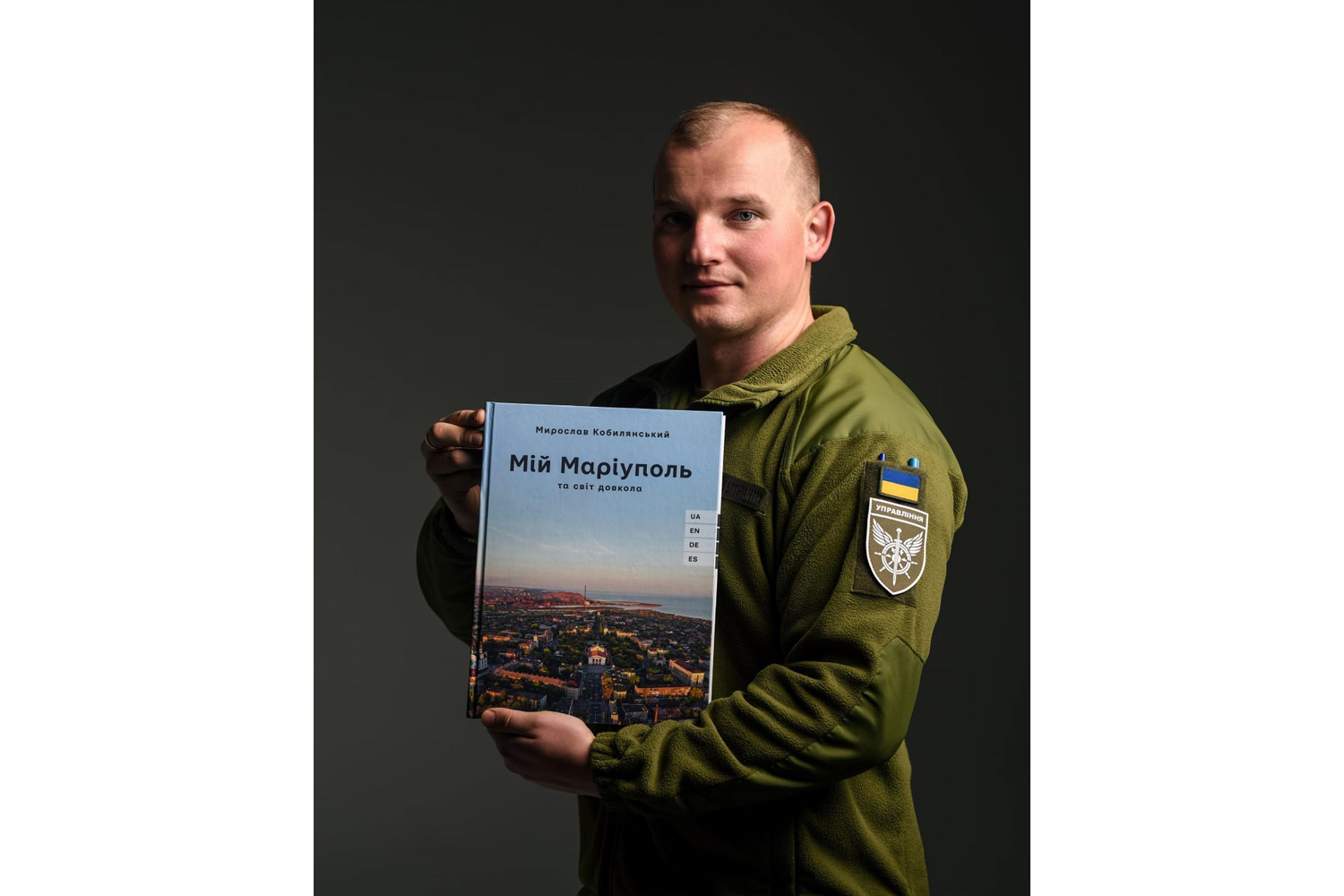

A photographer herself, Halyna has a special place for Myroslav Kobylianskyi’s photo album ‘My Mariupol and the world around it’, as photos from that book became her means of alleviating her emotional trauma, which attending meetings of a support group failed to provide.

Halyna shares that constant homesickness experienced by most IDPs makes it hard for them to feel at home somewhere else.

“I was stuck in that mindset of, like, speaking over the phone and telling the person on the line, ‘I’m almost home’, and then I’m stopping myself, ‘This isn’t home, it’s just a building I currently live in. So where exactly am I almost at?’ I’m working hard on letting it go, but the meaning of that word is never the same.”

Photo provided by the interviewee.

Halyna misses her native Mariupol, its people and the sea. She tries to keep in touch with both those who managed to escape and those who stayed in the city but who can’t call her up on the phone. She keeps talking in spirit to people who have gone missing. However, the Azov sea shore in Mariupol is something that she just can’t replace. The woman shares how she filled her new dwelling with items that remind her of the sea.

“I have a lot of postcards depicting the sea, depicting deep blue, and the postcards that my friends bring me from their travels. They are hanging on my walls, lifting my spirits. I also have a small plate of salt as a stand-in for sand, with some sea shells from different countries. Unfortunately, none of them is from Mariupol, however, I have some pebbles someone sent me from Berdiansk that is also under occupation, and I keep it all in my bedroom, close to me. I get up every morning and see those things, and I guess they are my psychological support on some visceral level.”

“It’s so important to offer safe spaces for people to share their stories”

In the fall of 2022, Halyna, along with other Mariupol citizens who escaped the blockade, was invited to an event in Germany. In Berlin, they told foreigners about what they went through when the Russian invaded the city.

“They took several of us, [as if we were] talking monkeys or something, to show to some foreigners. They were like, ‘See? These people are from Mariupol, they are real, they had to go through this and that, feel free to talk to them and ask your questions.’”

Photo provided by the interviewee.

The woman compares her experience with such talks with how she as a kid used to listen to WWII tales of her grandmother. To the audience, it’s just another exciting story of survival, however, they at least have an idea of what it’s like living through something like that in real life.

“And later, when you get a little older, you hear your grandma recalling her administering first aid to a German soldier, and you’re like, ‘Why was that soldier a German? How come he happened to be here [in Ukraine] back then?’ And that one little piece, a personal detail, gives you an entirely new perspective on what was really going on and how he ended up here. ‘Why did you have to do that? Where were our soldiers? What was going on in the first place?’, things like that.”

Halyna finds it hard to share her story, and even more so when it comes to details. However, she believes that’s the only way to keep the audience interested and involved, increasing the chance of spreading awareness of the full-scale war, specifically, on the blockade of Mariupol.

She mentions Oksana Stomina, a poet from Mariupol who also managed to flee the blockade. The poet, along with director Anna Zhukovets, facilitated an educational project on Mariupol in Berlin, where she recites her poems translated into German. Oksana’s poetry is a depiction of war, of Mariupol, and also of her husband Dmytro Paskalov, who has been held in Russian captivity for over 600 days now. He was a civilian, who used to work as a harbourmaster before February 24 2022, and who later took refuge in the Azovstal plant along with many others.

“POW exchange after POW exchange, and he’s not on the list, yet Oksana stays strong and keeps writing him letters in poetry, and keeps touring different European cities and performing for high-level officials and in high schools. After her performances, high school kids keep asking her to stay and tell them some more, their heads buzzing with questions like, ‘How can this be?’, ‘What do you mean there’s no means of communication?’, ‘Does that stuff really happen in our time and age?’, ‘Like, it’s been two years, and yet Mariupol still lacks proper communication services?’ and the like. Or they ask, ‘What do you mean you can’t drink the water, why?’, ‘Couldn’t you just call the emergency services back when Mariupol was under siege?’, those types of questions.”

Photo: Khrystyna Kulakovska.

A reader might be scared by what people have to settle for in order to survive. They might be in disbelief. I mean, it’s often that all we see is some text, and not a real person behind it. However, those stories affect us differently when you meet that person in real life. That’s why, stresses Halyna, it’s so important to offer safe spaces to people to let them share their stories.

“All those stories of melting snow for having some water to drink, or eating pigeons — they might come across as some exaggeration when you read them. However, when you see an actual person [going through that experience], it’s completely different. I believe that today is the age of sharing those stories in person. We may not be able to influence the big narrative in strategic communication. However, still, those little little stories may become the constant drip which will wear away the rock of propaganda.”