Colonies settled by the mostly forgotten today ethnic group of Zabuh Hollanders developed in Volyn, in the west of Ukraine, from the late 18th until the middle of the 20th century. They developed a unique cultural landscape, distinct from the nearby Ukrainian villages. In this article, we will explore who the Zabuh Hollanders were, where they came from, and what authentic traditions they have brought to the territory of Ukraine. This was made possible thanks to the recollections of the Zabuh Hollanders’ descendants, one of whom graciously agreed to share her family’s personal history.

*

The author of this article compiled memoirs and reminiscences of the Zabuh Hollanders available on Russian websites; she deliberately chose not to reference them to avoid publicising the media of the aggressor state.The Zabuh Hollanders have resided in Ukrainian territory since the late 18th century. They are called Zabuh, or sometimes simply Buh, because they settled along the Pivdennyi (Southern) Buh River; the name Hollanders is derived from the Polish word meaning “ a Dutchman”. The Hollanders initially settled in the rural areas of western Volyn, a borderland already populated by various ethnic groups. Their first settlement, Skerneva Holiendry, was established in 1787 in the territory near present-day Starovoitove. The Hollanders founded several settlements that endured to this day: Zamostychi (the present-day Rivne village), Oleshkovychi, Novyi Dvir (now Kupychiv village), Poliana (now Oleksandrivka village), Yaniv, and Karolinka (currently defunct). The largest settlement, Zabuzki Holiendry, is presently known as Zabuzhzhia village.

In the Polish and Russian censuses, the Zabuh Hollanders were recorded as Germans, complicating the accurate estimation of their population in Volyn. This identification most likely stemmed from their use of the German language in communication and shared religious denomination. Additionally, imperial administrations historically tended toward the unification of the subordinate population.

The ambiguous story of the Hollanders’ origin

The origin of Zabuh Hollanders became a subject of two prevalent versions, neither of which has been definitively confirmed. The German scholar Eduard Bütow, researcher of the group’s history and a founder of the German-based Society of Zabuh Hollanders, considers them descendants of the Dutch settlers. According to his theory, they migrated to the shores of Pivdennyi Buh in the early 17th century, establishing villages along the modern Polish-Belarusian border. In the 18th century, their descendants started developing the territories of present-day Ukraine.

At the same time, the German historian Helmut Holtz denies the alleged connection of this ethnic group with the Netherlands. According to him, the Zabuh Hollanders did not speak the Dutch language, practise Dutch customs, or wear national dress; additionally, they adhered to a different religious denomination. Instead, Holtz suggests they originate from Prussia, pointing out that most of their prayer books were published there.

Prussia

A German monarchy formed from the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg which existed from 1701 until 1918 and gave rise to contemporary Germany.Even before the Second World War, the Zabuh Hollanders lacked a clear understanding of their origin.

“Our ancestors do not belong to the Poles, neither do they belong to the Germans,” remarked Karl Ludwig, a representative of this community.

Valentyna Shvalikovska, a descendant of the Zabuh Hollanders residing in Luboml in Polissia, shared with us her family story.

“I once asked [my relatives]: ‘So your surname is Ludwig, where are you coming from?’ More likely, they were still afraid to speak at that time. I saw that they were extremely tense on this topic. But my grandpa’s sister showed me some old photographs. She took them out from a hiding place underneath the wooden floor. She said, ‘We were hiding our photographs because we feared someone might learn about us and deport us to Siberia.’ My great-grandfather had seven children, and he was deeply worried for their safety.”

Religion, education and cultural life

Initially, the Hollanders communicated in German. However, influenced by their Slavic neighbours, they eventually adopted a blend of Ukrainian and Belarusian while using the Polish language in their church services.

Source: The holding of the Rivne village library in the Liubomylskyi district of the Volyn region

Religion played a pivotal role in the lives of the settlers, particularly in their self-identification. The Zabuh Hollanders were Lutherans, adhering to the Augsburg Lutheran denomination in the 19th century. Typically, the Sunday services were conducted in the prayer houses. One such house, originally wooden and rebuilt in stone in 1933, has survived in the Oleshkovychi village; it now belongs to the Evangelical Baptist Christians. Valentyna Shvalikovska also mentions that her grandfather Mykola Ludwig had attended a kirche.

“It was not far away, in Rivne, and he went there because that was his faith.”

Kirche

The German word for “church”; some languages, including Ukrainian, use that Germanised version to denote the Lutheran religious buildings.If there was no church in a settlement, the parishioners would gather in somebody’s home. During major holidays, the Hollanders attended the central cathedral in Domacheve, present-day Belarus.

Since Lutheranism requires believers to be able to read holy books independently, each Hollander settlement had a confirmation school that taught religious dogmas. These educational institutions were funded directly by their respective communities.

Confirmation

In the Catholic rite, it is a sacrament of anointing children aged 7 to 12; in Protestantism, it is a rite of conscious confession of faith, practised by teenagers aged 14 to 16.

Evangelical Lutheran Kirche, Oleshkovychi (currently, the church serves to the local community of Evangelical Baptist Christians in the village of Oleshkovychi in the Rozhyschenskyi district of the Volyn region). Source: The Virtual Museum of Volyn Germans.

The first school opened in 1797 in Skernevski Holiendry, a settlement that no longer exists. Fourteen boys and eight girls studied reading, writing, elementary arithmetic, and hymn singing. In some cases, the curriculum also included an introduction to geography, drawing, and ethnology. Graduate students underwent an exam serving as an admission to the rite of confirmation. Interestingly, reading and writing had to be taught in Russian alongside German, although this requirement was mostly ignored. In 1887, the Senate of the Russian Empire ordered to subordinate all un-Orthodox schools along their property to the Ministry of Public Education for their further reorganisation and Russification.

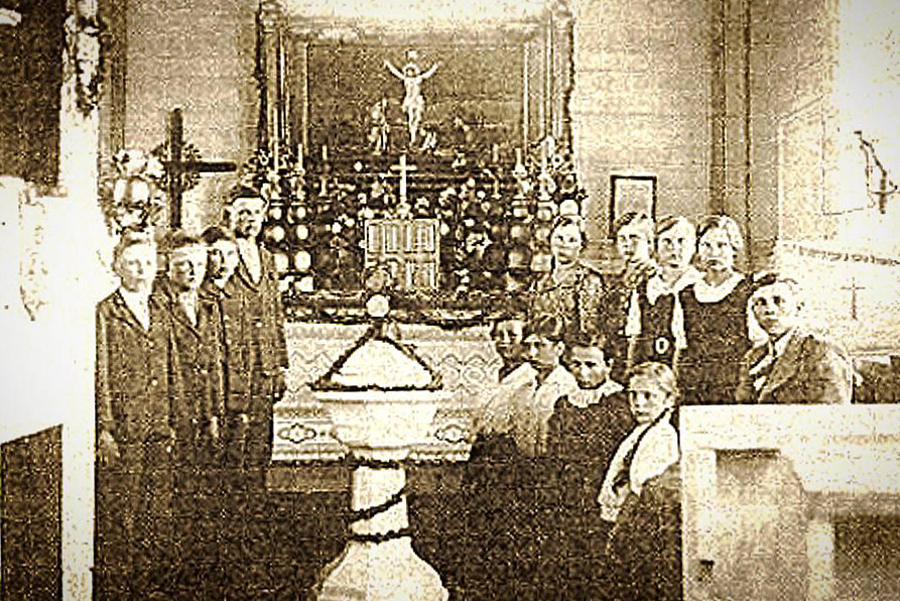

The confirmation ceremony in the settlement of Zabuzki Holiendry, 1930s. Source: Liubomyl Ethnographic Museum.

Religion strongly influenced family life for a long time, leading to marriages exclusively within the same religious community. Remarkably, the Hollanders have preserved their wedding traditions, even after their resettlement to Siberia, whether voluntary (due to the lack of suitable farmland) or forcible (during the Second World War).

Engagements occurred in the bride’s house, where bridesmaids, groomsmen, and matchmakers gathered. They used a hurypnik — a whip made of a goat leg adorned with satin ribbons — to conduct the proceedings. The celebration itself occurred on the second day. Interestingly, the Hollanders, like Ukrainians, served loaves of bread on the table, likely made from the same elongated dough, similar to the wedding cones – Ukrainian ceremonial pastries. Key customs included the bride and groom dance and the symbolic nailing of a cap, marking a farewell to youth. Tying the bonnet (a headgear of married women – ed.) was accompanied by a respective folk song closely resembling the Ukrainian language. After the festivities, the bride stayed at the groom’s house while, within a week, her parents organised the final ceremony – petrusyny.

Hurypnik

The baptism of the firstborn took place promptly after the birth. According to the Hollander beliefs, a prayer book known as ksonzhka was placed at the head of the baby’s bed to ward off evil spirits from taking over the baby’s mind or body. Families generally had many children.

After the First World War, especially among the younger generation, the Hollanders began engaging more actively with local Ukrainians. They jointly celebrated religious holidays like Saint Andrew’s and Saint Catherine’s Days. They also collaborated on staging theatrical performances featuring works of Ukrainian writers like Ivan Franko’s Stolen Happiness, Taras Shevchenko’s Nazar Stodolia, and Ivan Karpenko-Karyi’s Martyn Borulia. The Hollanders’ settlements typically hosted functioning brass bands that attracted Ukrainian listeners from the nearby villages. Over time, mixed marriages between the Hollanders and Ukrainians became more common. Valentyna Shvalikovska notes this occurring while recalling her grandfather’s story.

“[My] great-grandfather Ulian married a Ukrainian woman, so the whole family spoke Ukrainian; however, the great-grandpa also knew German. Everyone, for the most part, got used to Ukrainian. They peacefully co-existed with the Ukrainians without any conflicts. I remember that they went to Poland to trade. All borders were open until the Second World War, so the neighbours had no tension in their relations.”

How did the Hollanders manage their households?

The Hollanders generally managed their farming themselves without hiring labour. They were engaged in various activities, including agriculture, dairy farming, crafts, and trade. Valentyna Shvalikovska’s recollections shed light on their work ethics and skillfulness.

“[My grandfather’s father took care of cattle and was so pedantic that this meticulousness applied to everything. These curtains, benches, and floor belonged to my grandpa’s sister, and you can see how detail-oriented they were. It was a distinctive characteristic of my grandfather’s entire family.”

Source: The holding of the Rivne village library in the Liubomylskyi district of the Volyn region

The Zabuh Hollanders typically owned an average of 7-9 desiatyn of state-allocated land (approximately 22 acres), amounting to approximately 7,6-10 hectares per family. The land was adjacent to their houses, which was an advantage compared to Ukrainian peasants whose land allotments were scattered around. Because of this feature, local authorities often referred to the Hollanders as farmers. They cultivated various crops, including barley, rye, oats, millet, potatoes, and beans. In terms of livestock, they favoured horses, pigs, cows, sheep, and poultry, and occasionally kept goats. The Hollanders’ settlements often featured extensive gardens adorned with flowers.

Source: The holding of the Rivne village library in the Liubomylskyi district of the Volyn region

Their accommodation generally consisted of a yard and a wooden house constructed from boards that were joined together with clay. Valentyna emphasises that the Hollanders were relatively well-off for their times.

“At first, there was an apiary in a hamlet. Later, they would build a house in a settlement, a sturdy house covered with bliakha.”

Bliakha

Thin sheet metal with anti-corrosion coating.Typically, those Hollander yards near water reservoirs had their own bridge and a couple of wooden boats. The houses were elongated and featured living quarters, a passage, pantries, a barn, a threshing floor, and a hayloft. These sections, each with a separate exit to the yard, were connected by internal passages. The outer walls of the houses were usually whitewashed.

With the onset of the Stolypin reform (1906–14), which aimed to address the rural overpopulation in Volyn by resettling residents to uninhabited regions of the Russian Empire and redistributing the land, some of the Hollanders chose to relocate to Siberia. Today, their descendants are known as the Pikhtyn Hollanders, named after the settlement Pikhtynsk, that was founded by the re-settlers from Zamostychi in Ukraine’s Volyn.

Agrarian overpopulation

Significant unemployment among the population engaged in agricultural production, hindering the achievement of the necessary level of prosperity.Elena Ludwig, a descendant of the Zabuh Hollanders from Siberia, describes the interior decoration of their houses.

“Inside, we also whitewash the walls, adding blue colouring. Apparently, we are the only ones doing this. We believe it works well so we continue adding blue paint when whitewashing the walls.”

The house-museum of the Hollander Himborh (1912). Siberia

During the First World War, the Hollanders’ settlements were devastated as the prices of agricultural products significantly declined after the war. The Hollanders, therefore, started raising cattle to improve their financial circumstances.

The Third Reich or the USSR: the enforced choice of identity

In 1939, the USSR and the Third Reich signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, accompanied by the “Confidence Protocol” that addressed the status of the Zabuh Hollanders, among other issues. The Third Reich authorities regarded the Zabuh Hollanders as German people and sought to relocate them to the Nazi-controlled territory to prevent their natural assimilation among the neighbouring Slavs.

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

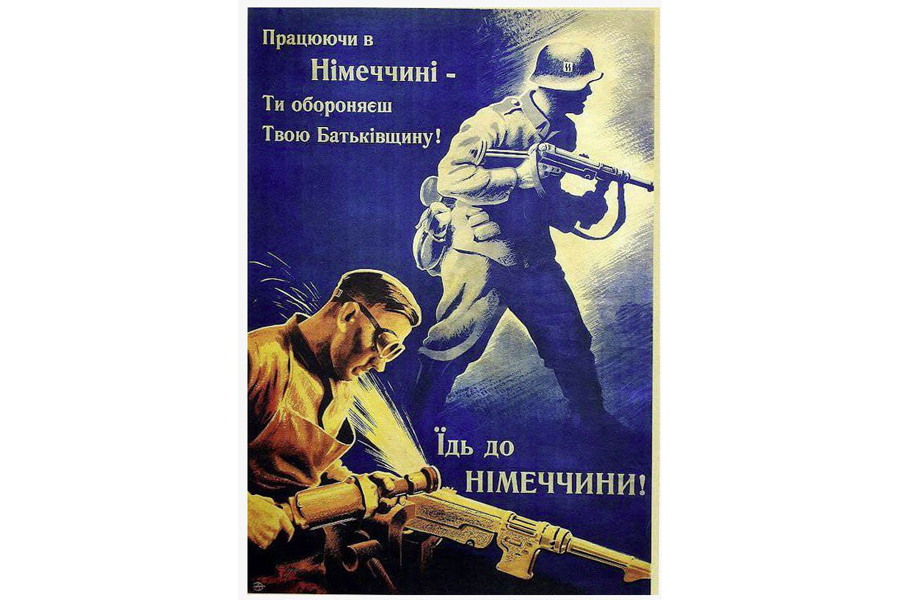

The non-aggression agreement between the Third Reich and the USSR signed on 23 August 1939. It established the spheres of influence between the two countries in Eastern Europe, stipulating the USSR’s non-involvement in German-Polish relations. Consequently, Nazi Germany attacked Poland.The agreement resulted in the launch of the active campaigning across Volyn employing leaflets, brochures and newspaper articles. Germans also widely distributed posters with slogans reflecting the Nazi ideology of the Hitler period – “One people, one state, one leader!” (Ger. “Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer!”). The German authorities appealed to patriotic feelings for their purposes, with the headlines screaming “Return home, the Fatherland is waiting for you and remembers you!”, “Germany is calling you!”, “By working in Germany, you are defending your Fatherland”.

The German poster “By working in Germany, you are defending your Fatherland!”

In January 1940, the Zabuh Hollanders faced a crucial decision between aligning with the Third Reich or the Soviet Union. This episode left a lasting impression on Bronislav Ludwig.

“The Germans came, and the Russians came. The river Buh became a border – the Russians were on one side and the Germans on the other. September, October, and November, and the war was over. In December, we were told that all Germans would be taken away. They said everyone had to leave the 500-metre area, which was left only for the patrol.”

Even though the Zabuh Hollanders did not identify as Germans, most were compelled to leave for Germany nonetheless. The 1921 Treaty of Riga enforced this choice on them, ceding the western part of Volyn, where the Hollanders resided, to the Second Polish Republic; this made their adaptation to the Russian way of life even more challenging.

The Treaty of Riga

an agreement between Poland and the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic that put an end to the Polish-Soviet War of 1919–20; the agreement finalised the division of the Ukrainian and Belarusian lands between these two states.Children and the elderly were transferred to Germany by train, while men preferred to travel on carts to transport their belongings. By February 1940, 2,280 Zabuh Hollanders had relocated to Germany. They were promised good jobs, higher salaries, and better food provisions; upon arrival, they were granted Third Reich citizenship, which legally guaranteed all these rights. However, the German population refused to perceive the Hollanders as their equals. They were derogatorily referred to as Poles since the majority of them did not speak the German language, communicating in Polish. Those Hollanders who refused to move to Germany soon faced an even worse fate, as the Germans populating the Soviet territories, including the Zabuh Hollanders, were viewed as Third Reich supporters. Early in the war, a telegram from the southern front commandment labelled the local Germans as “unreliable elements.” Consequently, the remaining Zabuh Hollanders were gradually deported to the Soviet labour camps in Siberia.

Ulian Ludwig, Valentyna Shvalikovska’s great-grandfather, was one of the few Hollanders from this region who managed to remain in Volyn.

“The history was silenced in my family because they were afraid, living in the Soviet Union at the start of the Second World War with all the deportations to Siberia occurring. It was rumoured that my great-grandpa was also considered for deportation. Somehow, he miraculously escaped [this fate]; however, his eldest son went missing.”

The house-museum of the Hollander Himborh (1912). Siberia

Some Hollanders attempted to address the situation by appealing to Germany for help. To some extent, they managed to improve their circumstances by obtaining documents that granted them Third Reich citizenship. Afterwards, they were relocated to the Polish city of Łódź and then to a refugee camp near Nuremberg, Germany, where they stayed from April to September 1941. Consequently, the Hollanders from Volyn were resettled on the ethnic Polish territories. Bronislav Ludwig recalls what the resettling process looked like.

“We were given a household, which turned out to be Polish. They (the Germans – ed.) kicked the parents out of the house while their sons worked for the Germans. And we were told: ‘This is your house now.’”

The local Poles were evicted from their homes as their area was adjacent to the highway used by the German army; the Hollanders were obliged to supply the soldiers with food. Additionally, the Third Reich’s leadership asserted the superiority of the German nation, stating it was the direct duty of the Poles to surrender their houses for its benefit. As a result, the new settlements of the Zabuh Hollanders became militarised.

Either way, the Hollanders ended up being strangers among their own. The war divided a single nation between various territories and states. One saying dating back to the German colonisation of the 18th century describes the situation remarkably well: “The first ones found death, the second ones found deprivation, and only the third ones found bread.”

The post-war fate of the Zabuh Hollanders

After the Second World War, the Zabuh Hollanders who settled in Poland had to hastily flee to Germany due to the arrival of the Soviet “liberation” army. The town of Linstow became the final destination for several families. Today, it is home to a museum dedicated to resettlers from Volyn and features a restored 1947 house belonging to one of the first Hollanders who sought refuge in the area.

Wolhynier Umsiedlermuseums, Linstow, Germany

Meantime, only a few representatives of this ethnic community remain in Volyn, as the Zabuh Hollanders naturally assimilated over time through intermarriages with the Ukrainians.

After the proclamation of Ukraine’s independence, the Hollanders who had previously moved abroad, mainly to Germany, were granted an opportunity to return to their homeland or visit it – a freedom that was prohibited during the Soviet era. Svitlana Klekotsiuk, the principal at the Zabuzhzhia village school, preserved the recollections of the Zabuh émigrés.

“Once, a woman from Germany visited us with her grandson. Born here, in Zabuh Holiandry, she was 83 years old [at the time of visit]. She said that during the Soviet period, they would come to Poland and go to the Buh River to look at the land on the other bank, where their garden and house once stood.”

Eduard Bütow, a native of the Zamostych settlement in Volyn, noted similar observations in his report from a trip to Ukraine in 1998.

“Fifty-eight years ago, there had been a street where our and my grandpa’s houses had stood, but now there was only a meadow. You could also now see partially dilapidated stables and several rusted agricultural machines of the former collective farm.”

Even though the settlements of the Zabuh Hollanders practically no longer exist, the local authorities still attempt to preserve the memory of people who lived side by side with the Ukrainians for centuries. In 2017, commemorative plaques were put up in the villages of Zabuzhzhia, Rivne, Zabuzki Holiendry, and Zamostychi to mark the 500th anniversary of the Reformation and the 400th anniversary of the first Hollander settlements in western Buh. The reverse side of these plaques lists the last names of the Hollander families residing in these villages in 1940. Following the ceremonial inauguration of these memorial plaques, the local ethnographic museums staged thematic exhibitions. Remarkably, an Orthodox priest and a pastor of the Evangelical Lutheran Church jointly consecrated the plaques. We can consider this as evidence of the organic intertwining of the two religions and cultures in the region.

The Reformation

A socio-political and ideological movement in Western and Central Europe of the 16th century that took the form of a religious struggle against the Catholic Church and its teachings.

Memorial of the Wolhynier Umsiedlermuseums, Linstow, Germany

Additionally, a cross with a commemorative plaque was erected on the site of the former Lutheran cemetery in Zabuzhzhia’s outskirts. Regrettably, the remnants of the church foundation and a few tombstones are all that remained from the cemetery. The graveyard in Oleshkovychi is in slightly better condition, with several gravestones relatively intact. In 2001, it was honoured by a commemorative plaque bearing the names of the settlers.

A commemorative plaque at the Lutheran cemetery in Oleshkovychi. Source: The Virtual Museum of Volyn Germans.

The Zabuh Hollanders who moved to Siberia still remember the Ukrainian language and songs. The local residents, who interacted with their delegation in 2017, remarked,

“They chat just like we do! Yes, they are ours, from Zabuh!”

During their visit to Zabuzhzhia, the delegation, for the first time, listened to the “Anthem of the Buh Hollanders,” performed by local schoolchildren. The lyrics, written by Oleksandr Mishchuk, a Germanist and professional translator from German in Lutsk, were set to the melody of the Ukrainian folk song “Unhitch the horses, boys.”

The funding from the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation and the Federal Ministry of Internal Affairs, Construction, and Integrated Territorial Development of Germany enabled the establishment of the Virtual Museum of the Volyn Germans in 2020. The project is dedicated to digitising the material and intangible cultural heritage of the German and the Hollander population of Volyn. Additionally, a historical route was developed as a part of the initiative, allowing visitors to explore the key sites related to these communities.

For nearly a century and a half, the Hollanders created an authentic cultural and social context in Volyn, where they resided. Their presence greatly added to the diverse traditions of this region, contributing to harmonising relations between its multiple ethnic groups.

Their input adds to the history of Ukraine as a diverse country where numerous ethnic communities coexist peacefully. Tragically, many of them had endured repressive policies, deportations, and forced Russification under various Russian regimes. Therefore, researching and documenting their heritage has crucial significance. The restoration and preservation of the Hollander’s legacy provides a solid foundation that empowers Ukraine to counteract the Russian disinformation and strengthens the nation’s resolve for a free future.