Before enemy tanks enter a country, the aggressor country “drives through” the culture. It plants its own narratives and suppresses the ones that dominate the territory. By wedging desired ideas into the cultural field, Russia creates a favourable environment for waging hybrid warfare. After artificially creating the loyalty to their culture in the neighbouring countries, the invaders are counting on having a carte blanche on the territories they want to occupy. Russia has been working under this scenario for years — appropriating Ukrainian cultural figures, erecting monuments to Russia’s leaders, and in every possible way pushing its low-grade content into the information space. Such statements as “the question of culture is irrelevant” or “what does Pushkin have to do with it?” are harmful narratives that threaten the national security of Ukraine.

“The Camouflage Net of Russian Weapons” is a multimedia project about the importance of cancelling Russian culture in the context of a full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine. Together with our partners — Lviv Media Forum (LMF) and House of Europe – we analysed how Russian culture contributes to war and why it is important to boycott it.

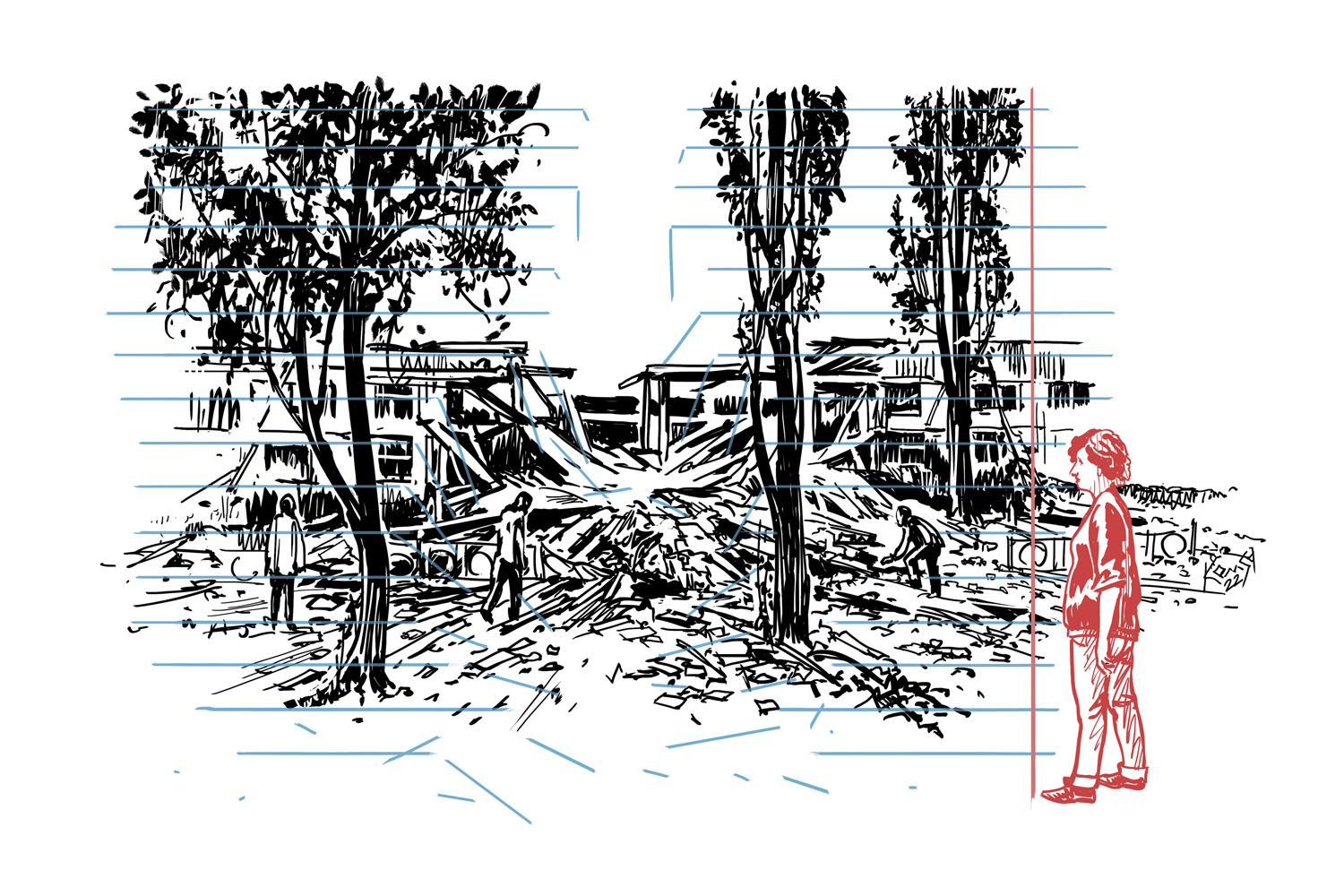

“We will now get rid of everything Russian. Everything,” a woman with tears in her eyes says. She’s a teacher of Ukrainian and Russian languages at one of the schools in Kharkiv. At the beginning of June, the Russian military fired missiles at this educational institution.

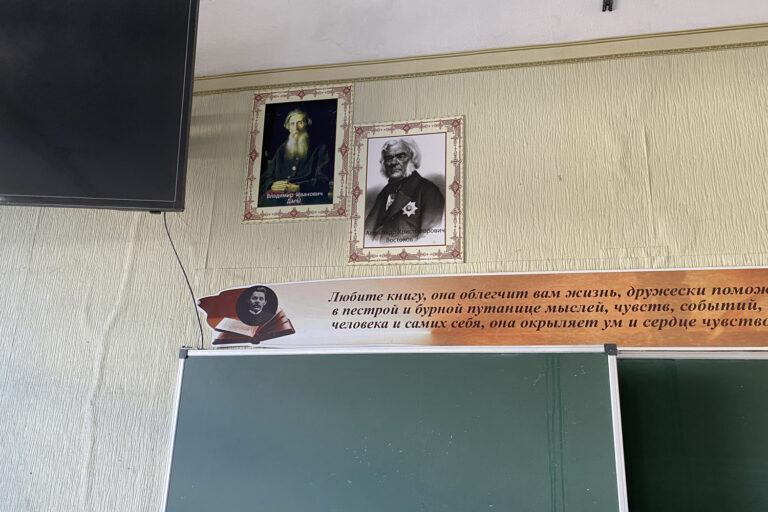

For several months, the school has been in a nearly ruined state: school textbooks are scattered on the floor, desks are overturned, but various bulletin boards with announcements are still hanging on the walls. In one of the classrooms, a portrait of Vladimir Dahl, a Danish-German lexicographer from Luhansk who compiled one of the largest dictionaries of the Russian language, also hangs above the blackboard.

Illustration. The teacher in Kharkiv

Below the portrait, there is a quote from another Russian writer Maksym Gorky: “Do love books, they will make your life easier. They will teach you to respect others and yourself, they fill your mind and heart with love for the world, for a human.”

12 years ago, in 2010, this school was the first and the only one in the Saltivka District to open a Sergei Yesenin Museum to honour the Russian poet. Locals were very happy about that, little did they know that 12 years later, a Russian missile would damage the building.

Northern Saltivka

One of the most densely populated residential areas of Kharkiv, built in the 1980s. The Russian army destroyed more than 70% of its buildings, at the time of publication of the material shelling continues.

slideshow

Russia’s imperial appetite dates back to the times of the Muscovite Empire. When Peter I came to power, he normalized the practice of conquering other states in order to expand the territory of his country. However, land grabbing was not the only way to go — the Muscovites expropriated the history of Kyivan Rus and began rapprochement with Europe.

Since Russian Tsar Peter I wanted to join the European cradle of civilization, in the early 18th century he launched national reforms which aimed at transforming the Asian-like state into a young European monarchy. The Tsar studied in Europe and was a big fan of the Western World. To make the empire legitimate, the Tsardom of Muscovy had to prove its right to belong to Europe and show its unity with this civilization. It was the reason why the Tsardom of Muscovy was renamed into the Russian Empire and started its expansion by conquering neighbouring countries.

The duality of Russian culture, when at first russians declared themselves as Europeans and then showed typical Asian behaviour, is the “mysterious russian soul” which has been attracting the Western World for centuries. This interest has not disappeared to this day, because Tsarist Russia for many years pursued a powerful policy of soft influence in other countries. Therefore, despite seeing the consequences of a full-scale war in 2022, many Europeans still do not understand (or do not want to understand) why it is necessary to cancel Russian culture. “This is Putin’s war”, they say. “What does it have to do with art?”

Ukrainian historian Yaroslav Hrytsak says that some of his foreign colleagues — educated, progressive people — began to support Russia precisely because of culture:

“On the first or second day of the war I got a message from an elder professor I respect very much, he is a good person. He became interested in Russian culture the first time he heard Tchaikovsky. The professor’s message said, “I hope Putin will conquer you soon and everything will be OK.” He said that sincerely, without aggression. He didn’t feel Russian culture was something bad,” historian Yaroslav Hrytsak says, describing his overseas colleague’s reaction to the war in Ukraine.

I’m speaking to Mr. Hrytsak in Lviv. The city’s streets regularly witness military funeral processions ever since 24 February 2022. At summer café terraces you see ordinary life only to bump into people dressed in dark clothes and hear them crying around the corner. Passersby stop, afraid of tampering with a mournful silence.

Soldiers are carrying two coffins — everybody present is bowing their knee meeting those who gave their lives in this war that started 8 years ago, in 2014. 22-year-old Vladyslav Leonenko and 33-year-old Anton Havrilov are being given the ultimate send-off. Is Russian culture responsible for these deaths? It is unlikely that anyone present will think about it now.

Illustration. The funeral procession

Every week, Kyiv also sees funerals of Ukrainian soldiers. After the Revolution of Dignity, Mykhailivska Square in Kyiv became a place of grief and struggle. Then, in November 2013, St. Michael’s Cathedral was a refuge for protesters in the capital, who were staying there day and night. After another attempt to forcibly disperse the protesters in the temple, the bells in the bell tower were rung for the first time in eight centuries.

Today, placed on the walls of the temple complex, portraits of the heroes of the Heavenly Hundred remind us of those events. Now they are supplemented by photos of the defenders of Ukraine who died in the full-scale war of 2022. For a moment, it may seem that they are now all looking at the destroyed Russian equipment, placed in Mykhailivska Square nearby, as physical evidence of the invasion of the Russian army and its crimes.

“It feels like they saw children and shot on purpose,” a young woman says to her companion looking at one of the exhibits — a car with a big sign saying CHILDREN, all stuffed with bullets.

The car attracts attention amid burnt Russian military equipment. There are passengers’ belongings inside the car and wizened flowers tied with a black ribbon on the windshield. Children and adults stop at this car for the longest time, examining every detail.

slideshow

Art historian Ilya Levchenko explains that it is important to differentiate art and culture. Art is a part of culture together with living conditions, traditions, values, and lifestyle of a nation. Art impacts culture, while culture shapes a person.

The writer Andriy Kurkov adds a valid remark about the peculiarities of Russian society:

“Russia, especially outside large cities, has always had a law of strength and violence. Until recently, the Russian cinema focused much on social injustice (refers to auteur cinema of the last decade — ed.). These films were made for foreign viewers, they were awarded at different festivals while Russians haven’t seen them. Because they haven’t been seeking justice, as they don’t believe in it. It means that injustice is normal in Russia. And if injustice is normal, then all ways to reach injustice are traditional”.

There is a huge difference between the product Russia has been showing the outer world and the way art influenced the internal audience. The Western World perceived Russian art as mysterious Eastern European fatalism, while in Russia, art continued to convince people that a small person in a big world can’t change anything. And it’s easier to surrender to the one who is stronger than to fight and die. Russian art has become a disguise for Russian Propaganda, while propaganda made the war possible.

Two middle-aged women (apparently, Russian women) are standing in line at a Viennese café:

“Hey miss!” one of the women addresses a waitress in Russian.

The waitress is looking at her confusedly and gets back to her work.

“Does she not understand?” the woman asks her friend.

Illustration. The Viennese café

A long Russian occupation of its neighbouring countries that were part of the sphere of influence of the Russian Empire, and later the Soviet Union, gave an international status to the Russian language and made Russians think that all people in the world should understand it. Meanwhile, Europeans are that it’s enough to know Russian to understand all of Eastern Europe. Russia has been taking advantage of this idea, spreading propaganda narratives around the world. With the beginning of the full-scale war, Ukrainians deepened their desire to get rid of the Russian language, which served as a tool of Russian aggression. Russians use the language to mark territories: if people speak Russian somewhere then Russia literally regards these lands as its territory, and therefore in their opinion, they have the right to invade it and establish their own rules.

Sviatoslav Litynskyi, a language activist from Lviv, explains:

“There was a survey in 2021 in Ukraine, in which people were asked what language they considered their native. If we now build a map based on their answers, we’ll see that 90% of territories where people considered Russian as their native language are now occupied. We see that the language border almost fully (+/-20 km) corresponds to the military one. And our army defends us as well as our language,” says Sviatoslav Litynsky, a linguist activist from Lviv.

He adds that before the Revolution of Dignity, in 2012, the amount of Ukrainian language in public had began to dramatically decrease. Particularly, a Ukrainian layout disappeared from laptops. The Kolisnichenko-Kivalov law (operated from 2012 to 2018) was adopted, which in fact made Ukrainian a secondary language. Svyatoslav says that then he felt that the authorities at that time sought to preserve the mentality of Ukraine as a colony of Russia, and it was necessary to fight against this. At first, empires invade other nations culturally and then militarily.

In the early 2000s, Lviv was one of a few places where you could really dive into the Ukrainian context. Back then, a tragedy deeply connected with the language issue happened in the city. Ukrainian composer Ihor Bilozir was killed in a local café. Some men at the next table, who were fans of the Russian criminal underworld music, didn’t like that Ihor and his friends were singing Ukrainian songs too loudly. The police officers stopped the verbal altercation, and when everyone left, unknown assailants attacked the composer and his friend, who were already on their way home. The composer was beaten to death. More than 100 thousand people came to his funeral. The killers were punished, but this situation deepened the feeling that you can die in Ukraine because you speak Ukrainian.

During the Soviet occupation (1944–1991), numerous Russian military families inhabited Lviv, including representatives of the NKVD. Then Lviv became mainly a Russian-speaking city, but beginning from the 1960s people from neighbouring towns and villages moved to the city and brought the Ukrainian language to Lviv.

The main Russian diaspora centre in Lviv was Pushkin Community, which functioned from 1996 to 2017. This place regularly held discussions on the necessity of the empire renewal and questioned the existence of the Ukrainian nation. The bust of Pushkin on the facade of the building was a good cover for the centre’s anti-Ukrainian activities, because cultural figures were not perceived as those who could somehow harm the state. Today, the renovated building houses the “Warrior’s House” veterans’ hub. Here, veterans and their families are provided with social, legal and psychological assistance, and various youth projects are implemented. Not a trace of Pushkin remained on the facade.

slideshow

For the last 400 hundred years, the Russian government has put the Ukrainian languageunder linguicide dozens of times. The 1863 Valuyev Circular in fact fully eliminated the publishing of Ukrainian books, which suppressed the development of Ukrainian literature for many years to come. The Ems Ukaz (order – ed.) in 1876 banned the Ukrainian language everywhere (theatre, church, music), and almost completely banned the publishing and import of books in Ukrainian.

A man at Odesa’s most popular and old market, Pryvoz, is struggling to buy cucumbers and speak Ukrainian to the merchant.

“We’ve been imposed upon with the Russian language for years, so now I barely speak Ukrainian.”

“I also want to start speaking Ukrainian, but I’m embarrassed,” says a woman standing by.

Illustration. Odesa Pryvoz

Back in the 19th century, Austrian writer, literary critic and translator Karl Emil Franzos (originally from Galicia, lived in Ukraine for 10 years) described Odesa as a European city where you could meet any ethnicity. In particular, Ukrainian speech and songs could be heard quite often on Odesa streets. The author cited a Kozak song he happened to hear in Odesa, “This is the battle song their fathers sang when fighting an enemy.” Franzos said that Ukrainians suffered the most from the aggression of their neighbours. In particular, from the Russian Empire.

During the 20th century, you could hardly hear the Ukrainian language in Odesa. The Soviet government invented a great working stereotype, “Ukrainian language is spoken only by peasants while modern city residents are Russian speaking.”

However, there were, of course, attempts to counteract total convergence. For example, since 2009, the festival of Ukrainian culture, Vyshyvankovy Festival, has been held until Independence Day. Since 2016, the city’s children’s and youth festival-competition of Ukrainian song “On the Wings of Song — from Antiquity to Modernity” has been held there.

Today, more and more residents of Odesa are becoming Ukrainian speakers. A language club created after the 24th of February is a great support to them.

“Well, what will you put up instead of Catherine’s monument when you take it down?” This is what a resident from Odesa says when she’s asked what the city should do with the monument to Catherine ІІ, former Russian empress of German origin. Why are Odesites arguing about this question? Catherine was consistently destroying the Ukrainian identity: she eliminated the Kozak movement, turned Ukrainians into serfs, rewrote history and banned the culture of Ukrainians. Moreover, Catherine never visited Odesa and died 2 years after the city was captured by Ukrainian Kozaks.

Meanwhile, Russian propaganda broadly uses the image of Catherine. Not for nothing did the first monument to the empress appear in Odesa in 1900. After 20 years, it was dismantled by the Soviet authorities. The pedestal was restored after 87 years — in 2007.

2007 — the year of Putin’s famous Munich speech, which in fact declared a confrontation with the Western World and revealed a desire to renew the Russian Empire. By the way, that was also the year when a monument to the Russian writer, Ukrainophobe Mikhail Bulgakov was put up in Kyiv. In a year, Russia would attack Georgia, and in 6 years — Ukraine. Meanwhile, the monument to the Russian empress is still in Odesa, marking the city as the empire’s territory. The “monument” question is relevant not only for Odesa, but also for the entire country, which still has many such artefacts of the imperial and Soviet past.

slideshow

As a result of the long-term colonial politics of Russia towards Ukraine, it is sometimes difficult to clearly determine what exactly was Ukrainian and what was Russian in Soviet art. In Soviet times, Ukrainian culture found itself in conditions of systematic extermination: any national differences were to be simply erased, or merged.

Russia, which for centuries oppressed Ukrainian culture, instilling the opinion of its inferiority both to the world and to Ukrainians themselves, has partially achieved its goal. Unfortunately, the extermination of representatives of the Ukrainian intelligentsia and their achievements, systematic attempts to assimilate all levels of Ukrainian life have taken their toll. Until 2014, the myth of the greatness of Russian culture was preserved in Ukrainian society. And although Ukraine suffered the most from such aggressive colonial politics, this does not mean that the culture of other countries is safe. By starting a full-scale war, Russia finally showed the world its true nature.

Half a year of the full-scale Russian-Ukrainian war is beginning to tire the world. Discourses about the non-involvement of Russian culture in the war are increasingly appearing. And this is precisely what the aggressor country is counting on. Cancelling Russian culture is an element of self-defence for every country whose identity is encroached upon by Russia. The cultural front is a powerful work front that also requires a lot of effort and cohesion. The disease of imperialism is trying to spread—and it is within our power to eliminate it.

supported by

Проєкт реалізується за підтримки ГО «Львівський медіафорум» та Європейського Союзу за програмою Дім Європи.